It was just a stray remark at the end of a guitar lesson last fall.

My teacher is a veteran musician whose band has had both major label and indie record deals, and he loves the analog, the human, the vintage, the imperfect. So it didn’t surprise me to learn that he still likes to mix tracks with an old analog board or that he has a long-time “mastering guy” who finalizes the band’s albums.

What did surprise me was the comment that he had for some time been testing LANDR, the online music service that offers AI-powered mastering. Pay a monthly fee, upload a well-mixed track, and in a minute, the system spits back a song that hits modern loudness standards and is punched up with additional clarity, EQ, stereo width, and dynamics processing.

After mastering, the end result should sound “more like a record,” but this stage of the music-making process has always required subtle value judgments, as every change operates on the entire stereo track. And well-trained humans excel at subtle value judgments.

So I was expecting some line about the slight edge that ears and hands still held over our machine overlords. Instead, I heard: “In the last year, LANDR has improved so much that it now sounds as good as, or in some cases better than, things we’ve had mastered professionally.”

AI-powered mastering systems allow endless tweaking (mastering engineers generally offer a specific number of revisions). They return results within a minute (mastering engineers might need up to a week). They are comparatively cheap (mastering engineers might charge anywhere from $30 up to a few hundred bucks a track, depending on their experience). And now they can sound better than humans? This statement, coming from a guy who won’t buy a guitar made after 1975, was high praise indeed.

I flagged the remark as something to investigate later.

A few weeks after our conversation, Apple released version 10.8 of Logic Pro, its flagship digital audio workstation (DAW) and the big sibling to GarageBand. Stuffed inside the update was Mastering Assistant, Apple’s own take on AI-powered mastering. If you were a Logic user, you suddenly got this capability for free—and you could run it right inside your laptop, desktop, or iPad.

So between my guitar teacher and Apple, the consensus seemed to be that AI-powered mastering was in fact A Thing That Could Now Be Done Well. Which meant I had to try it.

See, in 2023, I built a small home music studio for under a thousand bucks—gear is ridiculously cheap and high quality compared to the old analog era—and taught myself tracking and mix engineering. This was a surprisingly technical process. It took months before I knew my 1176 from my LA-2A or my large condenser from my dynamic mic or my dBFS from my LUFS. Mic placement alone, especially for complex analog instruments like acoustic guitars, took considerable trial and error to get right.

Alongside this engineering boot camp, I began writing songs as part of my long-sublimated desire to don the tight leather pants and bring real rock’n’roll back from the dead. I liked some of my compositions, too—not always a given in this sort of creative endeavor. The lyrics felt clever, the melodies hummable. I began to record.

But something stood in my way. Even as I learned proper technique and my recordings went from “meh” to “now we’re talking,” they never quite possessed that pro-level radio sheen. How to get it? Many people mumbled “mastering” like it was a dark art, as though some hidden final alchemy would “glue” your track together and lacquer it in a high-gloss finish, and they said this alchemy could only be performed by grizzled mastering engineers working with special mastering compressors and EQs of almost unfathomable complexity.

While this turned out to be a parody of the truth, it wasn’t completely wrong. I mean, if you were handed a mixed track and a mastering compressor (such as the one shown below), could you immediately start twiddling some dials and be sure you were actually improving the sound? What if you then went to work on the overall EQ balance of the track? What about adding tape saturation? What about increasing stereo width without sounding gimmicky? What about sibilance processing or other dynamic compression? What about knowing the many technical details around limiting and maximizing to hit loudness standards of the major streaming services?

I wasn’t sure that, without years more of ear and technical training, I would be capable of getting the sound I wanted. Tracking and mixing I could (barely) handle, but mastering felt like one discipline too many. So I had always planned on hiring a mastering engineer once I got an album’s worth of songs recorded. But now, here were tools promising to save me money and time while demystifying the “dark art” and making me sound more like an actual, serious musician? And they worked?

To those about to rock

To test these systems, I needed a song. So I descended into my writing cave and ripped off the chord progression from Def Leppard’s acoustic ballad “Miss You in a Heartbeat” (you need to watch the video for this song, if just to enjoy the almost literally unbelievable aesthetic choices). I futzed around with some guitar arpeggios. I plonked out some bass guitar rhythms. I built drum parts in Logic’s surprisingly capable Drummer tool. I chewed on the end of a pencil and stared at the blank page. And a story began to take shape.

It was the tale of a lovable loser who unwittingly performs the greatest of all forms of karaoke—late ’80s hair metal—before an audience of raucous country music fans. And he does it all while wigged and leathered up like an extra from Rock of Ages. Will he be blown off the stage by a blizzard of angry boos? Or will he forge a one-night detente in the Forever War between classic rock and modern country?

With the track penned, it was time to turn to my producer (me) and engineer (also me) and record this soon-to-be-classic track. I felt like my spare room studio needed a bit more sound absorption to track the acoustic instruments and vocals, so I hung some thick blankets and quilts on the walls. I turned off my home’s heating system to avoid background noise and shivered my way through performances on bass, guitar, keyboards, and vocals, which I then comped into single tracks.

Keyboard parts were all MIDI, using Logic stock instruments, but all instruments and vocals were recorded through a $180 Universal Audio Volt 2 interface and a $150 Audio-Technica 2035 mic. (This might sound cheap for a mic, but it’s actually a pricier model than the Audio-Technica used by Billie Eilish for her debut album.) I used Melodyne to pitch correct my vocals, as I am not a trained singer. I mixed everything in Logic using mostly stock effects/instruments and a few Universal Audio compressor and tape saturation plugins. When I felt good about the mix, it was finally time to bring in the AI.

The goal here was not to see what these tools could add to a major-label project recorded on a $300,000 budget at a big studio. That world is disappearing, and it was ever only accessible to a few. Those still inside it will continue to use mastering engineers.

The goal was also not to pick the “best” sounding AI-mastering service. So much depends on the quality and genre of your input track, plus the style and settings chosen for the AI, that this would be largely pointless.

No, the goal was instead to see if AI mastering could really be a “sonic accelerant” for the hobbyist, the amateur, the laptop producer, the opening act, the indie label, the Famous Artist doing demos in their home studio, or the mix engineer who has five minutes to send a band home with something they can play in the car.

More personally, I wanted to see if could I create, from a home studio with minimal gear, something remotely resembling the love child of a Mountain Goats and Fountains of Wayne song. Would it have that “like a record” sound? And would it sound good enough that someone might voluntarily listen to it twice?

An AI-mastered version of my song “Hair Metal Renaissance” is embedded just below. Give it a listen if you like, and then let’s talk more about the tech. At the end of this article, I’ll reveal which tool was used to master this version of the song and why I made that decision.

Above: “Hair Metal Renaissance” (mastered) by Nate Anderson

AI everywhere

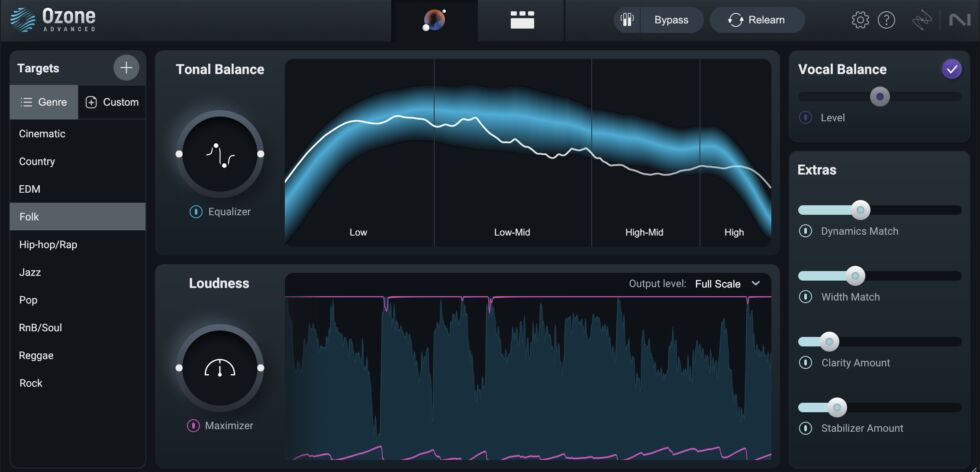

AI-powered mastering has quickly become ubiquitous. In addition to Apple and LANDR, the audio plugin makers at Waves offer an online AI mastering service. So does Brainworx, out of Germany. Master Channel has one. Or you can use Maastr. Bandlab provides few options but will do the job for free. And iZotope of Boston sells an expensive but gloriously complex mastering tool called Ozone that also does terrific one-click AI masters right in your DAW.

Like much about AI, this sort of work courts controversy. Is it OK to train a system on the EQ curves, vocal levels, and dynamic ranges engineered by humans, then build a product that might put some of those humans out of work? On the other hand—isn’t this way of “learning from humans” the sort of work that every apprentice in the studio and mastering business puts in when learning the craft? And while a cheap, quick, and (at least) competent AI master might be bad for mastering engineers, it’s a huge boon for the legions of bedroom studio and indie musicians.

Besides, say the companies behind these tools, they might not actually be bad for human mastering engineers!

“AI cannot fully supplant a human mastering engineer,” says Bandlab in a blog post. “It lacks the ability to sequence your record, discern errors like clicks and pops from musical material, tag tracks with metadata, and export them in the required formats for various distributors. It cannot operate a lathe for vinyl releases, either… It can still churn out a respectable result on a single song, given the right mix. In essence, it serves as an excellent tool for both mixing and mastering engineers to learn from.”

iZotope makes a similar case. In its 27,000-word (!) manual for Ozone, the company says its AI mastering tool can give beginners “the confidence to share your work with the world” and can give experts “a valuable second opinion and a faster setup.”

I reached out to the company to ask if this was just a bit of “corporate optimism” or a real thing that was happening in the real world. And while admitting that not all engineers appreciated AI-powered tools like this, iZotope did provide some interesting examples of how Ozone’s Master Assistant is being used:

A very common use case is that a professional producer/DJ will run their new song through [Ozone’s] Master Assistant before exporting to their USB stick and playing on a DJ set up. We’ve heard from mix engineers who run the audio through Master Assistant before sharing with a client so they can hear how a mastered version will eventually sound. For someone who is a pure mastering engineer, we’ve seen and heard them talk about playing “man vs. machine.” They’ll compare their master to Ozone and ensure that theirs sounds better. In this case, they’ll look at the changes Ozone made and occasionally see a potential improvement that they missed. Since it only takes a minute to get this second opinion, it’s worth it.

Bandlab and iZotope both say that the AI system need not be the final arbiter of what you hear—but it can be a great educational tool and safety net for double-checking one’s results. Because these systems are generally trained on a large number of reference works, sometimes separated by genre, they can provide a good sense of what a release in that genre “should” sound like.

Personally, I found this invaluable. As someone newer to the world of mixing and mastering, it’s easy enough to fix levels that are way out of whack. If my kick drum is absolutely smashing my eardrums in a sonic assault upon all that is good and decent, well—turn it down. Simple. But once a mix progresses to the point where tracks are mostly dialed in, making further adjustments can be extremely difficult. Is my kick drum now a tad overbearing, or is that just the “punchiness” a good pop track needs? Is my bass “propulsive” or just 3 dB too loud? At this stage, knob twiddling and second-guessing often sets in.

AI mastering tools like Apple’s Mastering Assistant and iZotope’s Ozone will listen to your track and provide custom EQ curves to bring your music into line with genre or style norms. (Most other tools I tried appear to apply EQ behind the scenes but do not necessarily show you the curves they are using.) This can provide tremendous feedback. If the AI tools make a 5 dB cut at 50–60 Hz, your kick drum is probably too loud by the standards of many other engineers who have worked on similar projects. That doesn’t mean you have to accept it, but it’s good information to have.

If the AI makes a boost at 100 Hz, your bass may be a little soft. If the AI applies significant midrange cuts, your vocal, synths, and guitars may be way too “present.” And if the AI makes a shelf boost at 12 kHz and you like the results, you now know that your track might benefit from a bit more top-end “air.” After hours of mixing, your ears and brain become accustomed to your mix choices so the AI can offer helpfully disinterested advice about what tweaks might still be made.

Whether this sort of thing is as useful to seasoned mix engineers as it was to me is unclear, but some mastering processes are more complex than turning a knob up or down. (This is especially true once you get into dynamic EQ, vocal clarity processing, mid-side processing, stereo width processing, and multiband compression.) It’s certainly possible that well-trained AI tools might offer a sanity check on one’s mastering decisions or provide alternative approaches, especially as decisions interact in complex ways.

Still, AI-driven tools alone will probably feel “good enough” to many performers, thus putting pressure on at least the lower end of the mastering engineer marketplace.

These tools do not sound identical, however, so picking the right one for your needs is crucial. Let’s take a look at four representative AI mastering tools—LANDR, Ozone, Apple’s Mastering Assistant, and Bandlab—to see how they work and then to hear how they sound.

LANDR

LANDR has been doing this work the longest; its AI mastering tagline is “The first. The best.”

Though some competing tools let you buy mastering credits or offer unlimited masters within your DAW, LANDR is mainly a subscription service, with plans ranging from $20–$40/month (or $140–$200/year). It began as a cloud-based system into which you would upload mixed tracks, receive mastered tracks in return, and then make “revision” tweaks through a question-based interface. (“How is the loudness? How is the EQ intensity?”) Once you’re happy with a master, it can be downloaded or pushed out to streaming services and social media through LANDR’s distribution system.

The mastering process itself is simple. The main option is choosing a warm, balanced, or open style for your track. (According to the company, warm offers “vintage warmth with softer compression for thick, smooth sound,” balanced creates a sound that is “controlled, with focus on balance, clarity, and depth,” while open is a modern sound “with emphasis on punch and presence.”) You can also upload a reference track that the system will analyze and try to match in style, but you don’t need to do so.

Once the system masters a track, you can listen to the result and answer a series of questions about it to generate a revision. Controls here are limited but do offer adjustments to sibilance, EQ, stereo width, and loudness.

For a little more knob-twiddling goodness and local control, you might try the newer LANDR mastering plugin. It slots right into your DAW on both Mac and Windows and is included with the higher-tier subscriptions (but can also be perpetually licensed for $299).

The plugin appears to be trained on the same data and to use the same underlying engine as the web-based version, but it runs locally on your machine and offers more fine-grained control than the online revision system. Just throw it on your stereo out or master bus as the final plugin, and it produces quick results after listening to just a few seconds of your track, with no waiting around while the web-based system churns through a revision and makes it available. Because it’s running right there in your DAW, the plugin also makes it simpler to step back, make some changes to the mix, and then re-master the project; no export and upload is required.

Running LANDR as a plugin also enables one more cool workflow hack: quick comparisons with other AI mastering services. To do this with web-based systems, you need to export and upload a track to multiple services, then keep multiple windows open (or download multiple files). It’s just… slightly clunky.

But when running things like Ozone, LANDR, and Apple’s Mastering Assistant as plugins on your DAW, comparisons are just a matter of clicking a button to switch one plugin off and another one on. I loved having the ability to dial up the best masters I could in three high-quality plugins and then simply cycling between as the song played back.

I preferred the plugin, but LANDR provided routinely solid results whether used online or run locally.

Ozone

iZotope’s Ozone plugin can be pricey—the most advanced edition retails for $399—but wowza. If you want to tweak settings and have access to every element of an entire effects chain, this is the tool you want.

Many AI mastering systems expose anywhere from “no” to “few” options, which can be a boon for musicians who don’t want to be paralyzed by esoteric settings. But if you’re the kind of person who mucks about in Linux config files for fun, you will love Ozone.

A one-click main screen lets the AI dial in a mastering chain for you, and it offers a few sliders to tweak the results. But you can also click over into the full mastering chain and alter every parameter of every plugin that the AI used to achieve that sound. (This also makes Ozone a great learning tool.)

Inside the maximizer plugin, for instance, you can pick your preferred algorithm (IRC 1? IRC 4?), adjust the “character” of the boosted sound, control “upward compression,” add or remove “soft clipping” of waveform peaks, adjust “transient emphasis,” and separately control the stereo independence of your transient and sustained sounds. And that’s to say nothing of the other six or seven plugins Ozone will often place before the maximizer—or the “whole-track” options like dither and codec previews. Personally, I found the sheer number of options, dials, switches, and displays to be brain-melting; luckily, the AI system did a terrific job on its own.

Ozone works a bit differently from many other services, which offer tonal options like “warm” or “vintage.” Instead, Ozone is based around genres. It will try to infer yours from listening to your track, but you can change it with a single click. Each genre comes with a different overall EQ curve, and Ozone attempts to match your music to the selected curve (a process you can watch play out in real time on the main Ozone screen). Ozone categorized my test track for this article as “rock,” but I found that the slightly lower mid-to-high end of the “folk” genre suited my preferences better.

Ozone can also match its mastered sound to that of a reference track you submit.

The company says that it has been using AI and machine learning technologies since 2016, and the experience shows. The AI routinely provided great-sounding mastering settings for the songs I threw at it. And if you want total control and advanced options, this is your tool.

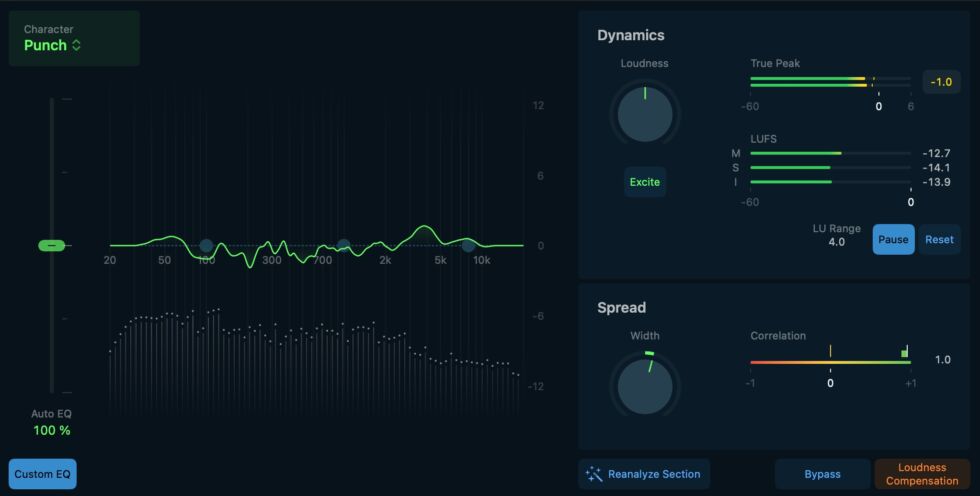

Mastering Assistant

Apple’s new AI mastering product is great—for a certain kind of user. It runs only on the the Mac or on the iPad, and it runs only within Apple’s own DAW, Logic Pro (which costs $199 for the Mac version of Logic Pro and $49/year for Logic Pro for iPad). But if you already work within that ecosystem, Mastering Assistant is a free and capable upgrade.

Mastering Assistant has a much more “hands off” philosophy to its design than, say, something like Ozone. That is, your hands should stay off most of the controls. (The actual mastering chain built behind the scenes is never exposed to the user.) The result is something more like LANDR’s plugin, offering a few tasteful style and EQ controls that offer solid results to those who don’t need or want to understand mastering’s intricacies.

Mastering Assistant can analyze your entire track—unlike LANDR and Ozone, which use only a few seconds of the loudest material to generate their mastering chains. On longer tracks, this can take more time than the other approaches, but it’s still a quick process overall; on an M1 MacBook Air running on battery power, Mastering Assistant took 100 seconds to process my 36-track demo song, while Ozone took 30 seconds. (You can also force Mastering Assistant to analyze just a section of your track by turning “cycle” mode on; this can be significantly faster.)

Results, as one might expect from Apple, are very good. Instead of trying to gauge your track’s genre, as Ozone does, Apple has opted for a “character”-based approach that offers Clean, Valve, Punch, and Transparent modes. (Note that the last three of these are only available on machines running Apple silicon.) These produce significant variations in sound and can give you everything from a tube-based, saturated analog sound to a pristine, “wide open” digital sound to a driving, mid-forward “modern” sound.

Apart from these four modes, Mastering Assistant exposes a few controls such as a loudness adjustment, an exciter for more top-end saturation, and a stereo spread knob. While the one-panel interface is simple and inviting—for instance, color shifts subtly remind the user of the currently selected “character” mode—it is not simplistic. Mastering Assistant offers a True Peak meter along with a LUFS (loudness units full scale) meter, plus a tool for measuring loudness unit changes within parts of your song. It also provides a correlation meter that can show how well your stereo track will reduce to mono.

In addition, it displays a composite EQ curve that shows you the exact changes it will apply to your track. (Ozone provides this, too, but you must dig into the mastering chain’s plugins; LANDR’s plugin shows the EQ of your track as you play it back, but it does not display a composite correction curve.) While all AI-powered mastering services make automated EQ adjustments, I found Apple’s the clearest when it came to education, providing solid feedback for my next mix if I sought to achieve a similar sound. For my test track, Mastering Assistant suggested a small boost at 60 Hz (suggesting my kick drum could be louder), a cut at 100 Hz (suggesting the bass was too loud), a cut at 600 Hz (clearing a little mid-range muddiness), and a 4 kHz boost (for vocal presence, I assume). While this EQ curve cannot be fully adjusted, Apple does let you dial its intensity up and down, and you can separately boost or cut the lows, mids, and highs of the composite curve.

In my limited testing, Mastering Assistant always made a track sound “better,” but it did not always make it sound like Ozone and LANDR. Perhaps this was a function of my own mixes or my settings, but Apple’s tool produced a more “open,” less compressed sound. Most of the other AI mastering services opted for a more modern, pop-style, compressed sound that works well on earbuds and laptop speakers but which has less dynamic range.

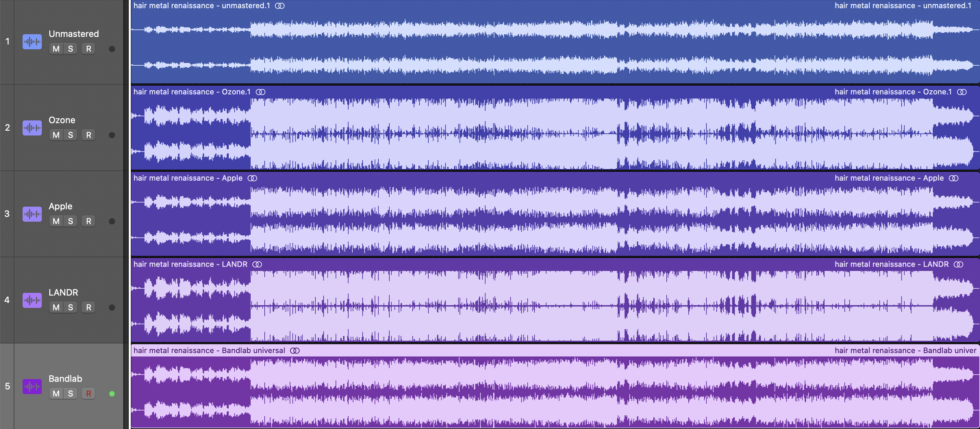

You can actually see this just by comparing the waveforms of various masters. In the example below, you can see my demo track in its unmastered form, stacked above mastered versions from the four AI mastering services discussed here. Even to the untrained eye, Apple’s version stands out for the extra space within the waveform’s boundaries—and this was audible to the ear, too.

Given the “black box” that is Mastering Assistant, I can’t say quite why this is happening, whether it’s just about my project or if it results from a basic difference in Apple’s approach. But what I can say is that is that these AI mastering do not all “give basically the same result on the same file,” even if all sound pretty good. It may be worth your time to investigate a few and pick the one best suited for your style or particular project.

Bandlab

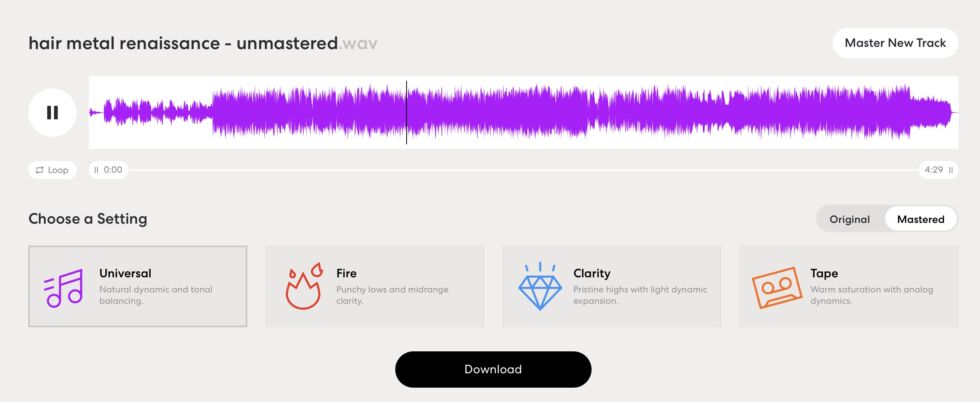

I chose Bandlab as a contrasting service to the others. It is web-based only and offers few options for tweaking or revision. But it is free.

And don’t underestimate the power of free! If you have some mixed tracks lying around and just want to see what AI mastering can do for you, Bandlab offers no-cost, no-strings-attached mastering so long as you create a (free) Bandlab account. And, you know, the results sounded… alright to me, though I didn’t find them as compelling as the other offerings.

Upload a track to Bandlab and it will crunch on it for a minute or so and then spit out a mastered version that you can preview right from the webpage. You have only four style options—Universal (natural), Fire (punchy), Clarity (“pristine highs”), and Tape (analog-style saturation and compression). Pick and preview the result, then download if you like.

That’s it; Bandlab has few other options. But did I mention it’s free?

How do they sound?

I ran my demo track through all four of the AI mastering systems described above, and if you want a sense of what each sounds like, the unmastered and mastered versions are all embedded below.

Do note that this is not an attempt to crown the “best-sounding” service. I did not try to force each master into the same style as the others, which would be difficult given how much their controls differ. Instead, I tried to dial in what sounded best (to my very subjective ears) from each system given my particular track and that system’s default sound. That might mean a warmer analog sound from a service that defaulted to something a little more clear and digital by default but a “transparent” sound from another service that used more compression and saturation. I also did not try to gain match the tracks so that you could hear just what each system does to a track’s “loudness.” What comes through, I hope, is a general sense of the subtle but significant sonic improvements that AI mastering can offer.

The examples below should be listened to on high-quality headphones or speakers, though the volume differences should be apparent even on earbuds. Note the ways that the Ozone and LANDR versions sound louder than the others, then pay attention to vocal clarity and the feeling of compression and space throughout the track—and how that affects the groove. To keep file sizes down, each version is a 320kbps .m4a file encoded using AAC.

Above: “Hair Metal Renaissance” (unmastered) by Nate Anderson

Above: “Hair Metal Renaissance” (mastered by Ozone) by Nate Anderson

Above: “Hair Metal Renaissance” (mastered by Apple) by Nate Anderson

Above: “Hair Metal Renaissance” (mastered by LANDR) by Nate Anderson

Above: “Hair Metal Renaissance” (mastered by Bandlab) by Nate Anderson

I liked most of the results I got. Mastering Assistant, Ozone, and LANDR were each clearly capable of pro-sounding results; the web-based services I tried, including Bandlab and Waves, were somewhat more variable.

Apple’s Mastering Assistant offered a less compressed and more open sound on my demo track, which sounded very nice. (Indeed, on another track of mine, I preferred Apple’s approach for precisely this reason.) LANDR was also great, though it offered a much more controlled sound. For this demo track, however, Ozone’s compressed-but-not-completely-crushed sound and its excellent handling of the overall EQ (the highs were present but never sizzling, for instance, and it dealt with one or two moments of sibilance better) won me over.

Ozone also kept my vocal clear while still making it feel “glued” into the rest of the track, and it added a nice sense of energy to the rhythm instruments that provided a slightly stronger groove. One downside of the Ozone approach was that the acoustic guitars sounded less open and jangly than in LANDR or Mastering Assistant, but I thought it worked for this track. The final result sounded good on my reference monitors, on my ATH-M50 headphones, and even on some terrible laptop speakers. Not bad for a songwriter working from a spare room.

Diamonds among the dreck

Who knows what AI will do to and for music in the future. Just consider what you can already do:

- Use ChatGPT to draft song lyrics

- Use machine learning to perform those lyrics in the voices of Drake and The Weeknd

- Create sounds using generative AI tools like Google’s MusicFX

- Mix tracks using AI-powered tools like Neutron and Cryo Mix

- Finish tracks with pro-quality, AI-powered mastering services

Humans will always make music, of course, but in 10 years, will we actually need humans to produce an endless string of pleasing pop confections? Perhaps not.

That may sound dystopic. But AI tools do have an upside: They lower the barrier to making music that sounds great.

It is really, really hard to write lyrics well, write music well, perform well, track well, mix well, and master well. Each is a different discipline, complete with its own body of knowledge and its collection of recordings, which are the codified wisdom of those who have come before. Each has traditionally taken many years to learn, which has meant paying a lot of money to a lot of experts and gear owners (studios, session musicians, mixers, mastering engineers, and distributors). Making professional-sounding music was thus tied to one’s pocketbook—but that’s no longer quite so true.

By absorbing the lessons of human trailblazers, tools like AI drummers, AI mixers, and AI mastering services do make possible a depressing future filled with the recycled dreck of the past. But they also open the gates of good sound to more musicians, more cheaply. They provide an automated version of “the rules,” which offer a good starting place for humans who then want to break some of them, whether lyrically or sonically.

And they helped me write a song about hair metal that, while certainly imperfect, sounds closer to “a record” than it has any right to sound.