Biographies of important South African musicians often fall into two categories: they either emerge from PhD or other university-based research, or are the fruit of dedicated digging by a fan or family member. The first kind benefit from institutional resources and support; the second from community knowledge of personal details that may be documented nowhere else.

Because of that very scarcity of a public record, the first kind might miss many parts of the story that can’t be checked in formal records and archives. The second risks being bent out of shape by hero-worship or fallible memory.

Maluks Books

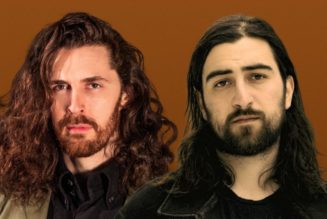

Sydney Fetsie Maluleke’s book The Life and Times of the Soul Brothers benefits from an author with a foot in each camp. Maluleke is a university-schooled researcher, but also an insider fan – he’s administered the band’s Facebook page and comes from a family who, by his own account, were even more fanatical than he is about the legendary band.

So the book, recently revised and relaunched for its second edition, combines the strengths of both kinds of biography, and avoids most of their weaknesses.

Who are the Soul Brothers?

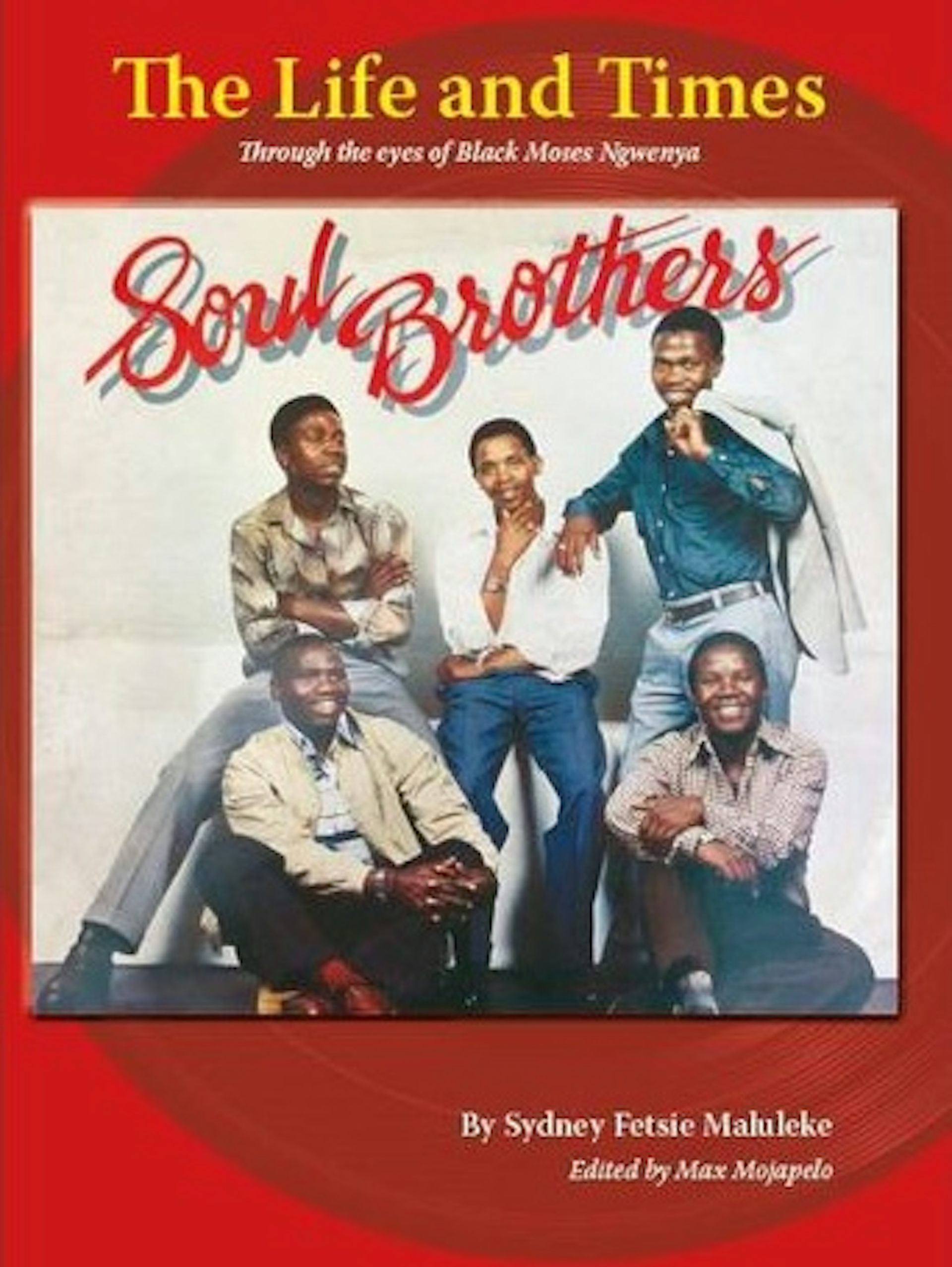

The Soul Brothers, formed in KwaZulu-Natal province in the mid-1970s by the late vocalist David Masondo and keyboardist Black Moses Ngwenya (and still working as a band today, though with new players), was the outfit that shaped the sound of South African mbaqanga. That’s the name of a popular genre blending traditional African vocal styles and lyrical tropes with transformed borrowings from western pop. It grew from a predominantly Zulu-speaking fanbase to dominate Black South African hit parades for more than a decade.

Gallo Record Company

The band scored multiple gold and platinum hits, and although their most recent studio recording was more than a decade ago, Soul Brothers music still gets radio play and is popular at family and neighbourhood parties. Soul Brothers were innovators. They drew in members from across language groups, and multiple inspirations, at the very time the South African apartheid regime was entrenching separation and difference.

Incorporating Ngwenya’s soul keyboard into what had begun as Zulu close-harmony vocals and guitar work was as startling an innovation for mbaqanga as US musician Ray Charles’ introduction of electric piano had been for American rhythm and blues.

Tired of exploitation by big, white-run record labels, the Soul Brothers also established their own label and studio, making them part of South Africa’s first generation of modern Black music entrepreneurs too.

Maluleke’s book takes us through all these developments. Though its subtitle describes the narrative as told “through the eyes of Black Moses”, he’s careful to source what he learns, label what is contested, and acknowledge that other interpretations are possible.

The book’s voice is resonantly human. Though chapters are organised thematically around the lives of various artists and the group’s stages of development, the story backtracks, repeats and comes at the same subject from different angles, just as people do when they speak. At points, I found myself hankering for more direct quotes from these insider voices and less paraphrase.

A new edition

The book’s first edition in 2017, Maluleke tells us, left out the setbacks and disputes from the tale, something for which Ngwenya himself gently rebuked the author. So in this second edition we learn also, for example, of the professionalism that permitted spellbinding and seamless ensemble performances onstage while, behind the scenes, the principals were literally not talking to one another because of disputes over leadership and power dynamics.

Gallo Record Company

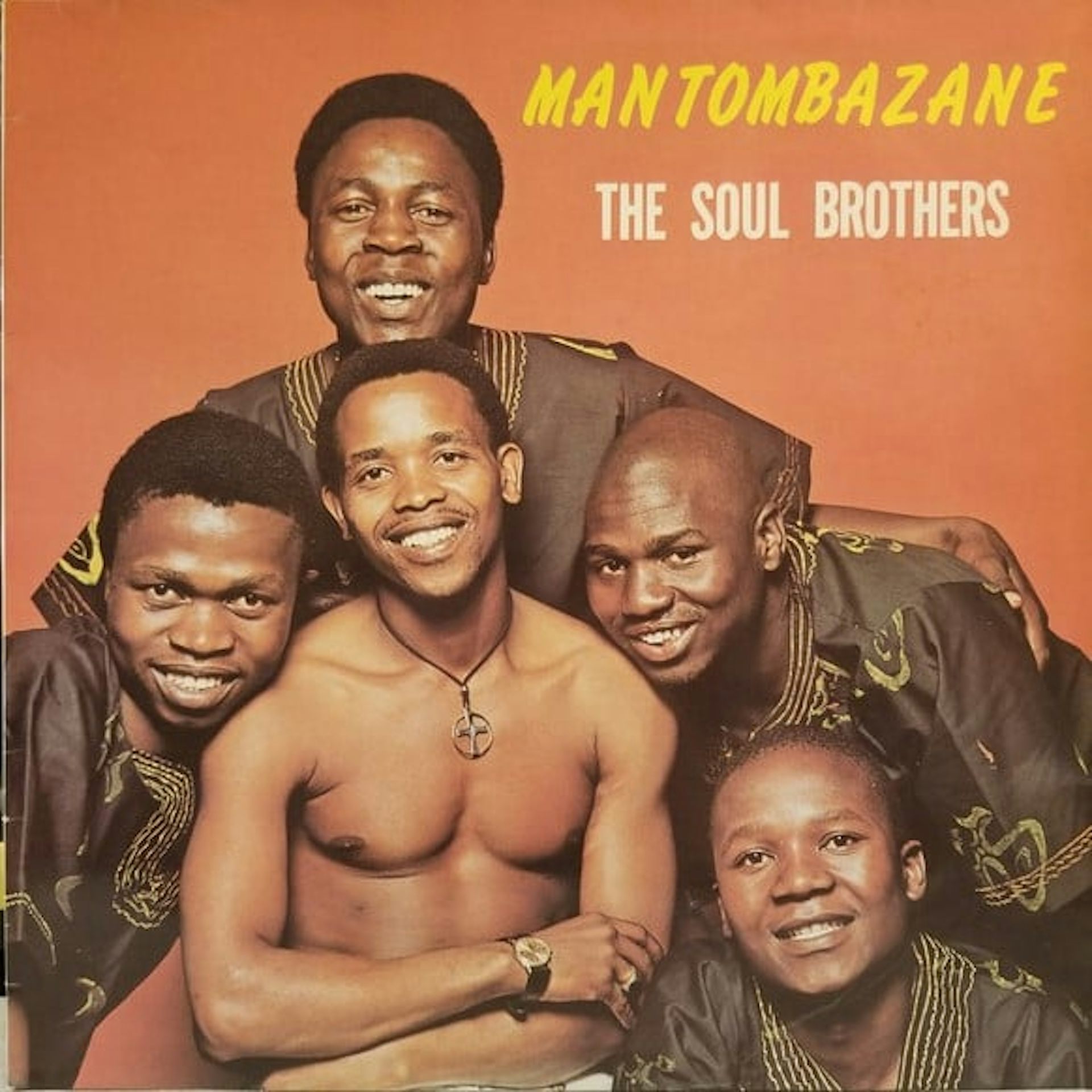

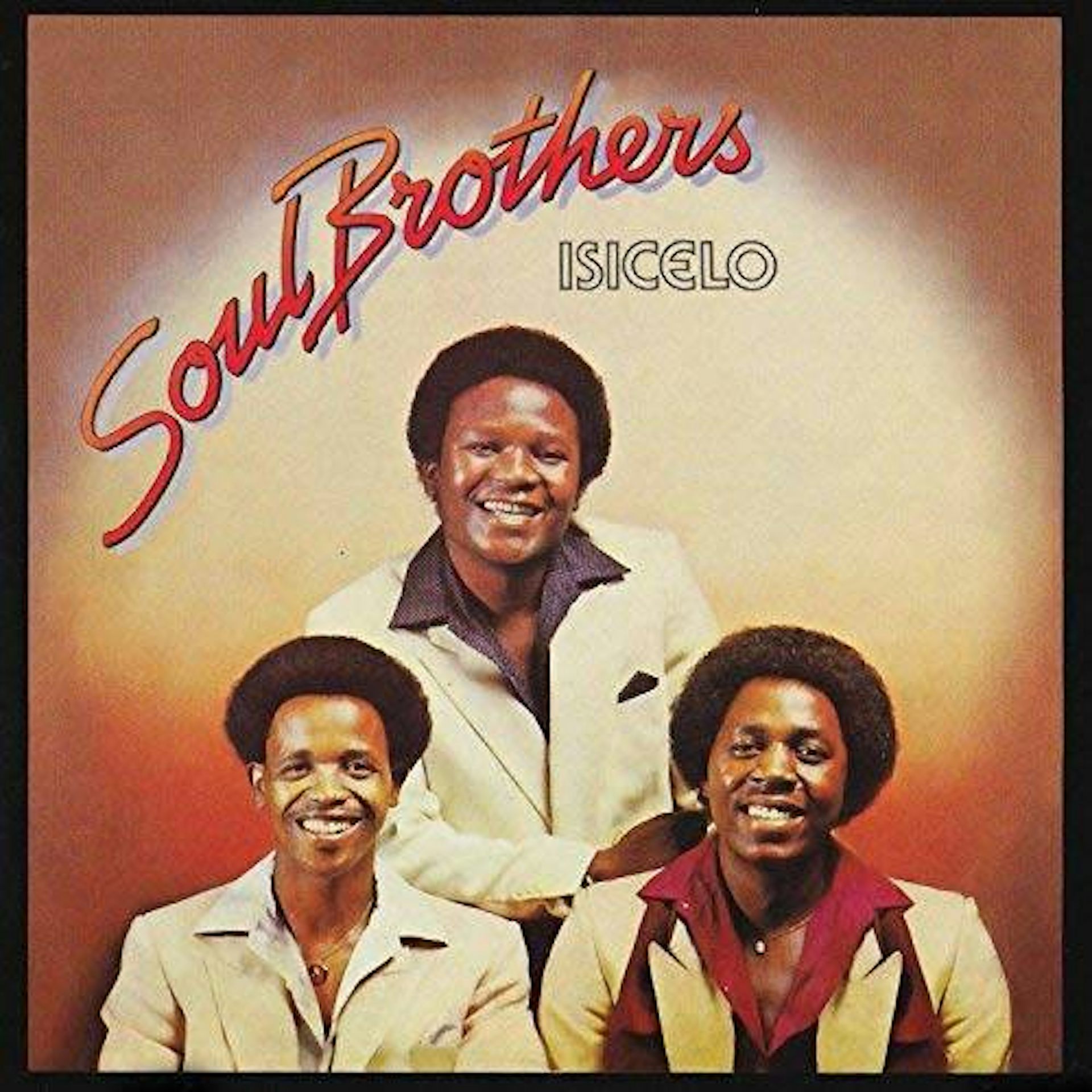

Maluleke and his family’s obsessive fandom, meanwhile, means there’s a priceless archive of press clippings, album covers and photographs to draw on. That provides nearly 40 pages of illustrative evidence to deepen the story.

Along the way, there are multiple bonuses not advertised on the cover: histories of associated musicians such as the veteran Makgona Tsohle Band, explanations of tradition, and descriptions of township community life more than half a century ago. Though the townships – segregated and impoverished areas for black workers removed from the “white” cities – had been designed by apartheid, residents built their own rich networks of solidarity, self-help and shared culture. Music was one of its pillars.

For me, a big surprise was learning that the young Ngwenya – regarded today as South Africa’s finest mbaqanga keyboardist – was inspired back in the 1960s by watching the rehearsals of the band Durban Expressions, whose keyboardist became one of the country’s finest jazz players: the late Bheki Mseleku.

All those are strengths that could make the book a storehouse of inspiration for music scholars. Each one of its details and detours could inspire a study of its own.

Some flaws

The book’s flaws, where they exist, emerge from the strains of producing a book on a shoestring budget. Maluleke, quoting Nigerian writer Chinua Achebe, wrote it because he was determined the history of lions must not be written by the hunters alone. The book did have one editor: veteran broadcaster and popular music expert Max Mojapelo, whose encyclopaedic industry knowledge no doubt enriched the history.

But it needed another, more prosaic kind of editor as well: a copy editor.

There are rather too many typographical errors and inconsistencies in, for example, the use of italics for song and album titles. Some date references are clearly unrevised from the 2017 edition. And there is no index; that makes the contents less accessible.

Hugely important story

Yet, if Maluleke had waited until more resources were available, he – and we – might still be waiting. A story hugely important for South African popular music history would have remained largely untold. He made the right choice.

Every music fan eager to understand how the “indestructible sound of Soweto” was born and shaped is in his debt.