Early in her musical career, when Alice Parker was composing and arranging for the Robert Shaw Chorale in New York City, the melodies she crafted seemed to magically transform into the performers who would sing each string of notes.

“I got to the point that I would sit down to write a solo for one of the people in the chorale, and the piece of paper I was composing on would become transparent,” she said in a 2017 interview with The Resonance Project. “I could actually see the singer singing the line. I was composing for a specific person, sound, and personality.”

A prolific composer of choral music, and a conductor and teacher as well, Ms. Parker spent more than 75 years providing artistic nourishment to performers and audiences alike.

“Music is exactly like food,” she told Resonance Project founder Jonathan Dimmock. “You have to compose for the people around you, the same way you’d cook for the people around you. Music is food for the soul — not just the mind, nor just the heart.”

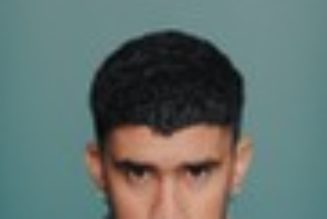

Ms. Parker, who completed her 2020 choral composition “On the Common Ground” in response to the world’s divisive strife, died Dec. 24 in her home in Hawley, to which she had moved full time at 70 and where she ran her Melodious Accord project.

She was 98 and her health had recently failed quickly, though up to the beginning of the pandemic in 2020 she was still traveling and leading seminars for musicians.

Composing on commission, she created hundreds of musical pieces that included cantatas and choral suites, song cycles, and full orchestral settings for choruses.

“From 1948 to 1968 she worked closely with the late Robert Shaw, doing a lot of un- or under-credited arranging for all those Robert Shaw Chorale recordings on RCA that an entire generation seems to have grown up with — ‘With Love From a Chorus,’ ‘Sea Shanties,’ ‘Sing to the Lord,’ and more,” the Globe’s Richard Buell wrote in 2000.

“It’s fair to say,” he added, “that Parker has even had a say in what a lot of Americans think a chorus ought to sound like.”

As a woman in a what was a male-dominated pursuit more than seven decades ago, Ms. Parker often encountered gender bias in how her work was acknowledged.

In 1995, Leslie Kandell noted in The New York Times that “when Alice Parker was working for the Robert Shaw Chorale, her name would appear in parentheses: ‘Haydn’s “Creation” (translated by Alice Parker),’ say, or ‘Folk songs conducted by Robert Shaw (arranged by Alice Parker).’ ”

During the past four decades, however, Ms. Parker was at the forefront of her endeavors, particularly after founding Melodious Accord in Hawley. The town had been her home away from home since childhood before she moved there for good in 1995.

Through Melodious Accord, she invited composers, conductors, and song leaders to weeklong seminars in Hawley, where they cooked for one another and ended the week with a community sing at a local church.

“Melody is an unparalleled means of communication for human beings,” Ms. Parker said on the organization’s website.

Choral music, she said in an interview for the ArtsHub of Western Mass website, provides a “kind of mind cleansing. You forget the struggles of the day and enter into the experience. The incredible thing is that this is right there for the taking, all the time. You don’t have to have studied. You don’t have to know anything. The smallest children, even babies, join in.”

Born in Boston on Dec. 16, 1925, Alice Parker was the second of five siblings and grew up in Winchester.

Her father, Gordon Parker, was in his family’s business importing mahogany.

Ms. Parker’s mother, Mary Shumate Stuart Parker, prepared school inspection reports in South Carolina before marrying. In Massachusetts, she helped start a laminate company that made propellers for military planes decades ago, among other products.

In 1920, Gordon purchased the land in Hawley that became Singing Brook Farm.

“I think I was 4 months old the first time I came here, and it has always felt like home to me,” Ms. Parker told ArtsHub.

At Smith College, she majored in composition, and then switched to majoring in organ upon realizing that she wasn’t fond of that era’s prevailing interest in 12-tone pieces, which generally dispense with Western music’s conventional hierarchy and distinction between consonant and dissonant intervals.

Her many honors and awards include receiving the Smith Medal in 2014. She was also featured in a Heritage Film Project documentary.

Ms. Parker received a master’s in choral conducting from The Juilliard School, and her association with the Robert Shaw Chorale proved rewarding professionally and personally.

Thomas Floyd Pyle was a professional singer, a baritone with the chorale who also ran a choral contracting agency in New York City. His work was so essential to the choral scene that singers arriving in the city were often encouraged to “go audition for Tommy Pyle,” the Times reported in 1964.

He and Ms. Parker married in 1954 and soon had five children.

They had “a very strong marriage,” said their daughter Molly Stejskal of Wyncote, Pa. “She had said that both of them agreed that it was important for her to be able to continue to pursue her career, and not just be a stay-at-home mom.”

When Mr. Pyle died of a heart attack in 1976, Ms. Parker, at 50, became a single mother to her children.

She continued to carve out time in a section of their New York apartment to compose on a slanted desk, its surface large enough to accommodate musical scores.

“At the same time, she was there for us,” Molly said. “So we just learned that when she was doing her music, we needed to let her be and we would have her attention later.”

The family will hold a private service for Ms. Parker, who, in addition to Molly, leaves two sons, David Pyle of Salem and Timothy Pyle of Powhatan, Va.; two other daughters, Katharine Bryda of South Hadley and Elizabeth Pyle of Amherst; a sister, Mary Stuart Cosby of Christiansburg, Va.; 11 grandchildren; and six great-grandchildren.

Molly said her mother “was really an optimist,” downplaying the infirmities of aging during doctor visits and living alone in her home until last year.

In 1990, Ms. Parker had purchased the mid-1800s building — long known as the Town House — that sat at the edge of her family’s property and converted into a place where she could live and work.

“I am absolutely delighted to stay here for the rest of my life,” she told the Globe in 2000.

In her final years, she drew on music’s call-and-response tradition to compose “On the Common Ground” as a plea of sorts for people to bridge their many gaps, including age, gender, race, and wealth. The title also refers to “the commons” – the common municipal space in many communities.

Music, Ms. Parker told NPR when she turned 90 in 2015, offers a common path to a common ground.

“I think it is meant to unite us as human beings in a way that nothing else can,” she said, adding that “if we are singing with our intuitive minds, we are concentrating on what unites us. Our common human experience and all life experiences can be sung about.”

Bryan Marquard can be reached at bryan.marquard@globe.com.