The Compassionate Music of Meshell Ndegeocello

Helen Shaw

Staff writer

January—stay with me, those of you looking at the weather report—is absolutely the best time of year in New York. The holiday crowds have dispersed, resolutions haven’t been broken yet, and the year’s finest festivals for the experimental performing arts all take place in the course of a few weeks. It’s a binge, a marathon, a bonanza: in only around twenty days, these fests program as much avant-garde performance as the city will see in the next eleven months. The shows are often short, and if you time it right you can get to three or four mind-bending things in a day. I think of January as a time to power-clean my calcified senses. If you blast a dozen or so shows through your sticky old brain, I promise that you’ll emerge fresh and new for 2024.

The Under the Radar festival (Jan. 5-21) has been the marquee name on the January festival circuit for many years, but it had to recover swiftly from an abrupt departure from the Public Theatre by co-producing its efforts with more than a dozen different spaces. I’m often in despair about how few foreign theatre productions we get in New York, apart from British imports, but U.T.R. has still managed to bring in several pieces from overseas, including work by one of my all-time favorite companies, the Italian group MOTUS. Also: there’s something beautiful about a festival that ties New York closer to the global community rallying with its own community so that it can go on.

The Fringe Encore Series (Jan. 4-Feb. 11), at SoHo Playhouse, programs award-winning shows from places like Brighton Fringe, Edinburgh Fringe, and the Hollywood Fringe—which means it’s the place you’re most likely to catch the next “Fleabag.” (My prediction for that position is probably Cassie Workman’s “Aberdeen,” which I’ve been hankering to see since reading about its run in London.) Still, the closest thing New York now has to its own Fringe in January is the Exponential Festival (Jan. 5-Feb. 4), operated from the Brick Theatre, in Williamsburg, and spanning many venues in Brooklyn. Exponential is interested in cutting-edge local work, and its offerings are the rawest and most adventurous of the bunch.

The new opera productions in the Prototype Festival (Jan. 10-21) will be, by comparison, polished and gemlike, but it, too, is carried off like a pub crawl through all types of New York venues: the BAM Harvey, La Mama, Irondale, an outdoor space at Battery Park. And the Live Artery festival (Jan. 9-20), produced by the dance venue New York Live Arts, evades definition. I’m excited to revisit two shows in Live Artery that surprised and awed me last year—Lisa Fagan and Lena Engelstein’s “Deepe Darknesse” and Dynasty Handbag’s “Titanic Depression,” in which Leonardo DiCaprio’s character from “Titanic” is played by a cartoon octopus who disguises himself as a hat. What? Simply trying to remember the bonkers details of “Titanic Depression” is deliciously destabilizing. Even now, I can feel its abrasive absurdity salt-scrubbing the grooves of my mind.

Spotlight

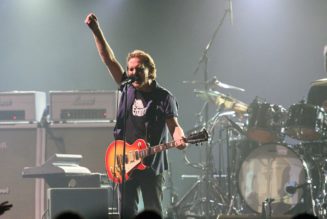

Meshell Ndegeocello is the most significant bassist this country has produced since the advent of Charles Mingus and Flea. But, unlike those innovators, Ndegeocello, who performs an upcoming series of shows at the fabled jazz club Blue Note, doesn’t really stick to one genre. Her incredibly musical ear and voice—she’s a fine singer, too—takes from jazz, soul, pop, and opera (as in her tribute to James Baldwin) to make sounds that are resonant not only of the times but of her very deep and compassionate soul. Ndegeocello’s latest album, the sensational “The Omnichord Real Book,” is a testament to her continued belief that music, like life, only gets better when we make it together.—Hilton Als (Blue Note; Jan. 9-14.)

About Town

For three decades, An-My Lê has interrogated the representation of war through the preënactments and reënactments of armed conflict: staged battles, training exercises, film sets, and the myriad ways in which it is performed, rehearsed, or mythologized. The work on view in “An-My Lê: Between Two Rivers” charts how conflict embeds itself in both physical and psychological terrains. Even as Lê’s photographs reduce hulking aircraft carriers to toylike size, her closeup portraits of rank-and-file soldiers and technicians evince an expansive empathy for her human subjects. In one image, as sailors set up a shooting range, their bodies map onto the contours of their targets’ silhouettes a little too precisely. Lê’s photographs function as an act of repair, uncovering subterranean histories in order to witness them anew.—Dennis Zhou (MOMA; through March 16.)

For someone who regularly plays bad guys—including a Tony-nominated turn as Hades in “Hadestown”—Patrick Page is damn likable. His gentlemanly charm and ravishing basso profundo serve him well in his solo show, “All the Devils Are Here,” in which he makes the case for Shakespeare as the inventor of the psychologically complex villain. This baseline appeal, together with Page’s passion and feel for the material, on display in monologues or dialogues as Richard III, Iago, and others, keeps the audience on his side even when doubts occur. What about Medea? And why include Malvolio but not, say, Brutus or Cassius? Despite Simon Godwin’s well-paced direction, which builds to a gasp-inducing speech from “Macbeth,” this disquisition seems more suited to a lecture hall than the stage.—Dan Stahl (DR2; through Feb. 25.)

In 2021, a severe car accident left the alto saxophonist Lakecia Benjamin with a fractured collarbone, a fractured jaw, and a broken shoulder blade, prompting a need not just to reset but to be reborn. The album she was touring at the time, “Pursuance,” from 2020, honored the legacies of Alice and John Coltrane with thoughtful reimaginings of their work; but in the wake of the accident Benjamin desired to more clearly commune with others in her compositions. “Phoenix,” her first album since, is progressive spiritual jazz that revels in resurgence. The transcendental music—constructed around collaborations with the scholar Angela Davis, the jazz pianist Patrice Rushen, the poet Sonia Sanchez, the late saxophonist Wayne Shorter, and more—blends her formidable instincts as a star-in-waiting with her immense impulse to venerate other greats.—Sheldon Pearce (Birdland; Jan. 14.)

Beth Morrison and Kristin Marting have lodged the multidisciplinary Prototype Festival, which they founded in 2013, in New York’s classical scene, on the strength of their unflinching belief in the power of contemporary opera. This year’s lineup explores religious and folk mythologies of womanhood (“Terce: A Practical Breviary” and “Malinxe”) and the human effects of the war on terror and the death of capitalism (“Adoration” and “Chornobyldorf”). “The theme, if there is one,” Marting says, is that of “an outsider trying to find their relationship to the forces of a society that is different from them.” For Morrison, it’s the prerogative of living composers to illuminate such issues with a musical language that listeners hear as their own: “We’re telling the stories of our time in our vernacular.”—Oussama Zahr (Various venues; select dates Jan. 10-21.)

The curator of this year’s American Dance Platform, Melanie George, starts with her own field of expertise—jazz dance—and expands from there. The first of three programs combines the Dormeshia Tap Collective, paying fiery tribute to under-recognized Black female hoofers, with the elegant jazz-vernacular meditations of Josette Wiggan and the second-line strutting of Michelle N. Gibson. Other programs feature Soles of Duende, a trio of aces in tap, flamenco, and kathak who share a gregarious spirit, and Dallas Black Dance Theatre, bringing new work by Chanel DaSilva and Norbert De La Cruz III.—Brian Seibert (Joyce Theatre; Jan. 9-14.)

In 1981, after seeing dance performances by Pina Bausch’s Tanztheater, Chantal Akerman made a choreographic film of her own, “Toute Une Nuit” (“One Whole Night”), a modernist melodrama about the varieties of romance unfolding on a hot summer night, in several neighborhoods in her home town of Brussels. The movie (scantly released in the U.S. and screening in MOMA’s program “To Save and Project,” which runs Jan. 11-Feb. 4) is built from a crisscrossing series of encounters of lovers, whether longtimers reconnecting or new ones meeting, in cafés and corridors, in taxis, by phone. With a cast of seventy-five, Akerman films the roundelay of mad dashes and timid introductions, ardent embraces and tender dances, in the form of stylized gestures that—as in Bausch’s work—are both banal and sublime.—Richard Brody (MOMA; Jan. 23 and Feb. 4.)

Pick Three

The staff writer Parul Sehgal shares three of her favorite novellas.

1. Lately, I’ve encountered too many lapsed readers. They bemoan how they used to read, and would read, but since the pandemic—or cue any contemporary horror—the active surrender that reading requires (especially fiction) feels too absorbing, too risky, when one must maintain a state of constant alert. Over the holidays, I gifted the lapsed readers in my life three novels—all short, recent (allowing my malingering readers to justify them as a kind of “news,” which, of course, they are), and, most important, irresistible. The first, “Ghachar Ghochar,” by Vivek Shanbhag, translated from the Kannada into English by Srinath Perur, is the story of the breakdown of a marriage, and it is a perfect piece of literature—swift and harrowing, constructed out of the simplest language and the most inextricable moral tangles.

2. “Small Things Like These,” by the Irish writer Claire Keegan, feels like a cousin to “Ghachar Ghochar,” with its velocity and its plain, radiant prose. A coal merchant discovers a young woman imprisoned in a convent. As with Shanbhag’s novel, we see an entire social order and a history made manifest—or rebuked—in a single moment, in a character’s single choice.

3. Eva Baltasar’s “Boulder,” translated from the Catalan by Julia Sanches, is the most recent of the three—a ragged, sensuous story. Read it last. After the two previous books that are very much about misogyny, here you will meet a gorgeously untethered woman wondering just what to do with her freedom. A book about new life for a new year.

P.S. Good stuff on the Internet: