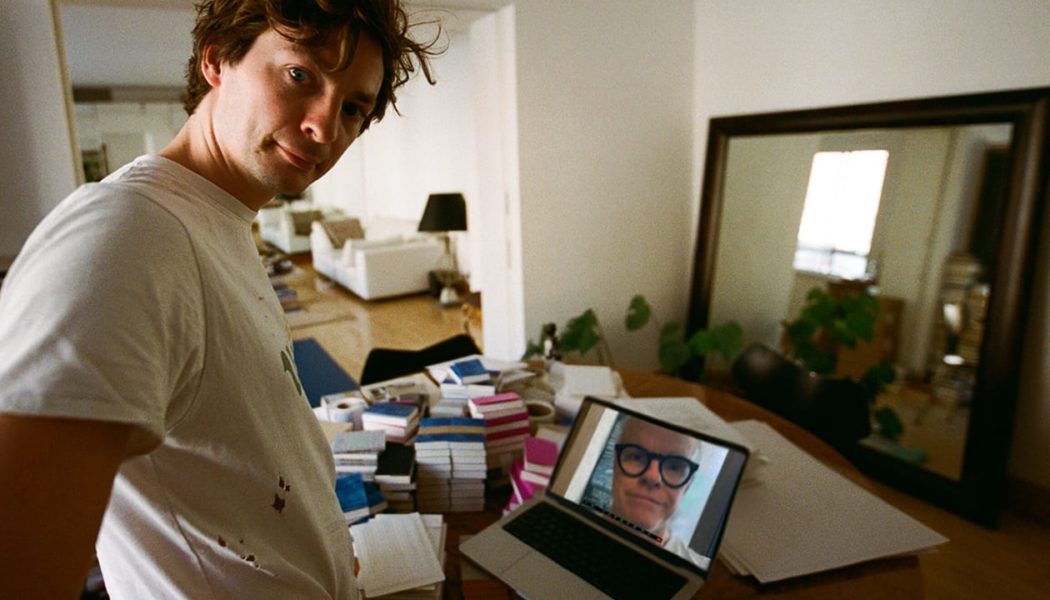

ISOLARII is a media company with an avant-garde approach to publishing. Founded by Sebastian Clark in 2020, the independent publisher is known for its palm-sized books as well as its dedication to challenging the established image of literature from aesthetics, distribution to function.

Described by its founders as more of an “avant-garde writer’s room,” ISOLARII’s books are accessible only via subscription. This in turn cultivates a tight-knit community of readers who are collectively committed and interested in the publishers’ books that often center around its network of top figures from our generation’s cultural, creative, and literary spheres. As for aesthetics, ISOLARII taps Alaska Alaska, the late Virgil Abloh’s creative firm to handle the design aspects of its publications.

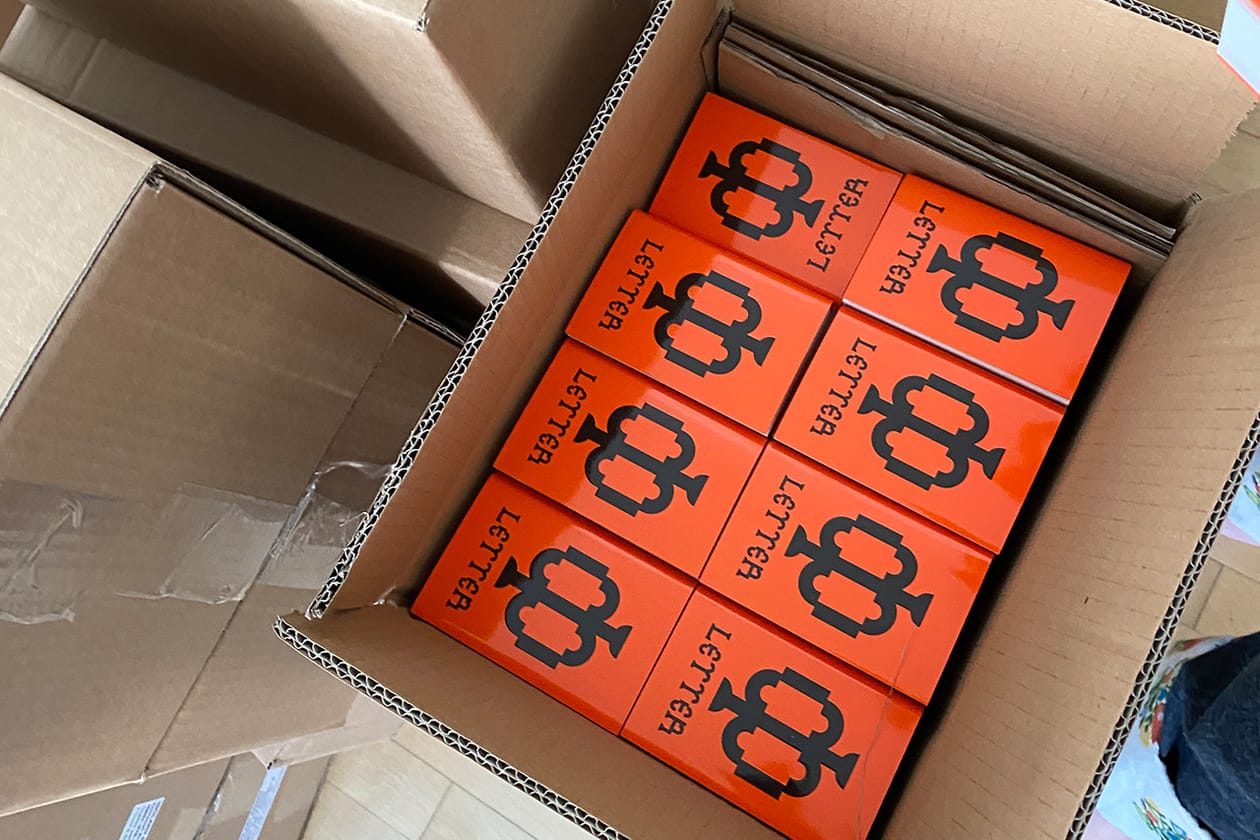

Unveiled earlier in the year, ISOLARII season two is the second installment of the publishing company‘s experimental project that consists of a sporadic release of pocket-sized-edition books. Hans Ulrich Obrist’s Ever Gaia is one of ISOLARII’s series of mini-releases for the second season. The book details a conversation from around 2015 between Obrist, a respected curator, art critic and historian, and the late environmentalist and proposer of the Gaia Hypothesis, James Lovelock.

Obrist is joined by Sebastian Clark for a discussion that centered on their experiences in publishing, art, and fashion, while also bringing light to the unconventionality and rebellious nature of ISOLARII. Read on for their exclusive conversation for Hypebeast.

Hans Ulrich Obrist: Someone recently said to me that ISOLARII reminded them of when Margiela appeared – that ISOLARII are to books what Martin Margiela was to fashion in the early ’90s. There is a similar mystery.

Sebastian Clark: Margiela is a forever icon – no one could ever reach his heights. But fashion houses or publishing houses, maybe there is no difference. Our only aim – whatever the product – is to deliver, beautifully, even if chaotically, what we think the times demand. At the moment, that is your book, Ever Gaia on James Lovelock.

HUO: Well, it launches a new season, which is something you would very much associate with fashion. What is this second season about?

SC: I think we’ll only know when it’s over. A second season is a way to say: we went once, found a way to do a few new things in literature – and now we will go again, and take another step in building a “media company”. I say it like that because I only ever want us to be a “company” insofar as we are the company we keep.

“ISOLARII are to books what Martin Margiela was to fashion in the early ‘90s.” – Hans Ulrich Obrist

HUO: Would you say ISOLARII is a brand? It is an interesting position to occupy, being a “company,” of which of course there is a history in visual art – the Bernadette Corporation, for instance.

SC: I guess so. All that it means to be a brand is to have a disposition and an attitude toward the world, which people trust you to deliver on. And to build a brand is to follow your intuition, and find your disposition.

HUO: What is that disposition? Do you think it is your own?

SC: To try to “tell the news” as it needs to be told: poetically. From project to project, to swing between extremes, the soberingly real and the wildly imaginative – something I think our generation does with great skill. It’s also to respond quickly and thoughtfully in ways other publishers cannot – that’s the disposition, and I think that’s my own too. I want to entertain everything – and make the case, if only for myself, that the human adventure is not over.

HUO: You’ve brought a very unlikely group of people together. Of a new generation like Cooking Sections from London, Yevgenia Belorusets from Kyiv, alongside figures like Can Xue, Art Spiegelman.

SC: Whether they are well known or not, they are all people I think are legends. All people I would bank the future of the world on – who, I believe, have the capacity to alter it materially through writing; who collectively can equip us for the times.

HUO: Or what Bill Cunningham says about clothes – armor to survive the reality of everyday life.

SC: Totally. There’s no building knowledge in many ways without collecting things. Whether it’s clothes or books, it is only through collecting, even if only memories, that we come to know ourselves. For Cunningham, this, I think, gives us the narratives of ourselves that, for him, is armor. So books and clothes serve similar functions in many ways. But part of me thinks it’s very important to kind of play and interfere with this, particularly when building something that is often called a collection.

“There’s no building knowledge in many ways without collecting things. Whether it’s clothes or books, it is only through collecting, even if only memories, that we come to know ourselves.” – Sebastian Clark

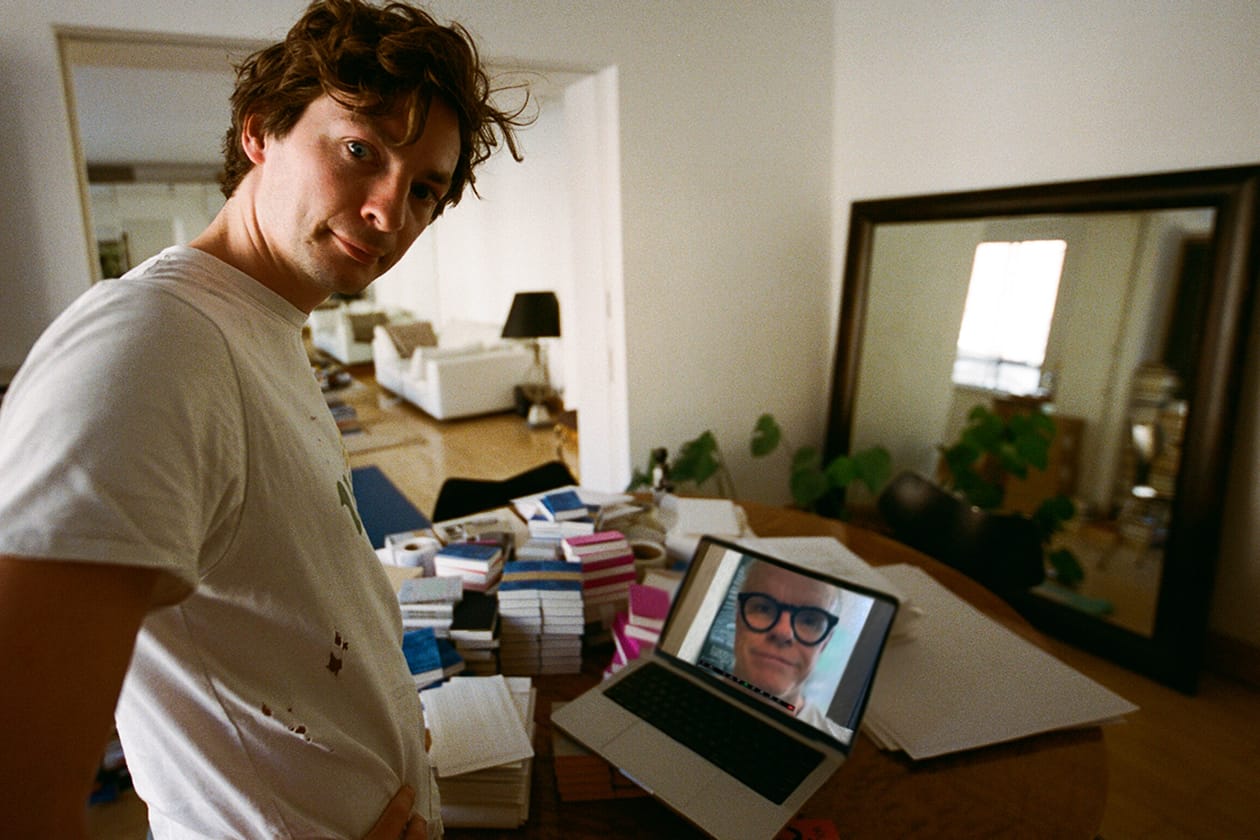

HUO: It is perhaps the size of isolarii that makes them collectible. It is an invention in many ways. What was the thinking?

SC: It is a way for us to say: what might be contained in the tiniest is not limited by the greatest–and that making things smaller can let you do things in a much bigger way – to f*ck with scale.

This ties to the practical reason why isolarii are so small. This is so that we can distribute them, literally ship them all over the world with immediacy, in a way that maybe even Penguin Random House can’t. So it’s the format itself that gives way to the international community that we’re building.

HUO: I was wondering whether we could maybe talk about this. I’ve always been interested in the idea of how we can disseminate art differently. Every industry has its distribution channels. Christian Boltanski said let’s come up with new channels: why don’t we do an exhibition in which everyone can take the artwork away? Make hundreds of thousands of copies of the artwork, so you’d take a bag, take the artwork off the walls, and take it home. But at the end of each day, the stocks will be replenished. This means that the exhibition can continue everywhere, around the world, on people’s walls – almost like a positive virus, as Felix Gonzalez Torres always said.

In the book world, there are ISBNs and ingrained distribution channels – you circumvent that and set up your own distribution system so you can send anything to anyone spontaneously. You never know what you will receive, it’s like Christmas each time it comes.

SC: As others have said, influencing the world today is not about writing new manifestos, but instead, developing new protocols for how we operate and determining how things are produced, how they circulate, and in turn, how reality is materially composed.

As a brand, you’ve got to think, “What’s the protocol I’m putting out there?” Sure, you can design some great graphics, put them on a hoodie and open a Shopify store – plug-and-play commodity capitalism – but you’re not changing anything. That kind of fashion is just trend-baiting, producing, and differentiation without any meaningful difference. That kind of fashion is running on fumes. Inject the unexpected where it doesn’t belong and rearrange things in doing so.

“Sure, you can design some great graphics, put them on a hoodie and open a Shopify store – plug-and-play commodity capitalism – but you’re not changing anything.” – Sebastian Clark

HUO: It is like when we launched our Glissant book in your first season at the Alicia Keys concert for a thousand people in Miami. Everyone walked away with a copy and it unleashed a tidal wave of people from the bus, from the beach, from the street, posting on social media about Édouard Glissant, who otherwise maybe wouldn’t have encountered him. You could also imagine that this happens at a concert at Wembley, or in the 100th hour at Glastonbury, and 200,000 people suddenly have the book all at the same time.

SC: Yeah totally. I’m a great believer in synchronicity, synchronous media, and the idea of people experiencing something at the same time. In the era of Netflix, it is undervalued. That’s what you did with Glissant – you created this moment where you were able to bridge popular culture and philosophy, and put Glissant’s totally essential worldview into so many new hands. Speaking of which, it is worth introducing Ever Gaia, your book on Lovelock, to Hypebeast’s audience.

HUO: Sure. It is important because there are few people who anticipated our current reality – on the brink of AGI, amidst a climate crisis – as Lovelock did, who died last year. He arguably kickstarted the Green movement in the 1960s, and his Gaia theory, developed with the amazing scientist Lynn Margulis, showed how all life on Earth is mutually self-sustaining. He is integral to making sense of this moment. More than that, the book is about his inventions and micro-inventions and, in detailing his life, is a guide to how we might invent as he did.

SC: So, indeed, a “book that equips us.” You’re also currently working on a project about artists as brands right?

HUO: Yes, with Viscose. It’s about the idea that artists are brands, versions of themselves. And amongst a younger generation of artists, they often have brands, fashion brands, and publishing brands. There is a contemporary history of artists, like Martine Syms with publishing, and Alex Israel, who have brands. For some, it’s almost like merch is an artistic medium.

SC: In fashion, unlike a lot of visual art, there isn’t any pretense that clothes are not commodities – so it’s a more honest medium in a way. Clothes are for you, the consumer; they mix into your life in a way that is unique to you, but I think you feel a strength in knowing that other people have those same, identical things, in a way that is unique to them too.

So it makes sense to me that artists would play with that, particularly in an era that is so concerned with the construction of identity. Fashion, as Emmanuele Coccia has said, can be a Trojan horse.

We are currently designing an ISOLARII uniform with the incredible GR10K. I want to think of a “uniform” as a format in the way the books are. We’ll only ever have one shirt or pair of trousers at a time, and each will be made from the deadstock of a highly technical professional uniform from the likes of mountain rescue teams in the Dolomites to electrical engineers in Spain. I’m interested in uniformity during a time when it seems like everyone needs to be hyperindividual.

“Virgil [Abloh] … spoke to millions of people of a younger generation about artists like Piero Manzoni … I think that’s the value of ISOLARII also being in the fashion world; you bring knowledge to it that it wouldn’t have otherwise.” – Hans Ulrich Obrist

HUO: ISOLARII works with many designers who reach into fashion – you’re currently working with Alaska Alaska, the studio of my late, dear friend Virgil Abloh, and with the young Swiss designer, Ben Ganz at a critical time in his career. While many might not know Can Xue, they’ll know Virgil. And by virtue, Alaska Alaska, his legacy in London, along with Samuel Ross. I think it’s very interesting that you’ve decided to work actively with the fashion world.

SC: Yeah, Tawanda and Francisco (from Alaska Alaska) and I have been in dialogue for a few years now. The way they think is brilliant, and, despite obviously being influenced by Virgil, who I did not know, it feels like they are committing to a beautiful chaos that is very much their own. I think they’ll be two of the designers who radically shape our generation.

HUO: I met Virgil very early in his career, as you and Alaska Alaska have. We met, and the next day he texted me asking if I would come to Amsterdam to introduce him to Rem Koolhaas and so I went. That was the start of many brilliant dialogues.

SC: The way I think of you both is that your imprints are so perfectly light. You move, as did he, between things with such ease. Italo Calvino wrote that having lightness is the most important quality of this century. That’s something you and he shared – a kind of lightness that resists the world turning to stone.

HUO: Well, the other thing that Virgil did was that he spoke to millions of people of a younger generation about artists like Piero Manzoni or Lucio Fontana, and I think that’s the value of ISOLARII also being in the fashion world; you bring knowledge to it that it wouldn’t have otherwise.

SC: Exactly, it shouldn’t matter whether you know the author. It’s better that you don’t even. The best ideas often remain unknown to you, and if we only encounter what we know, the world is boring.

HUO: You’re working with Philippe Parreno, right? What’s that like?

SC: Incredible. He has totally influenced what I think literature can be. What people don’t know about him is that more than anything, he is a writer. Everything he does begins with him sitting down and writing – which he then brings into reality in such technologically and temporally complex, and still sensitive, ways.

HUO: And, finally, is there an end goal for ISOLARII?

SC: No, at least not yet. I just want to resist a world in which we’re constantly updating to remain the same – whether that’s a software update or a new bag. That’s a boring world; I’m here for irrationality, the chaos of a world in transformation. No more updating to remain the same.