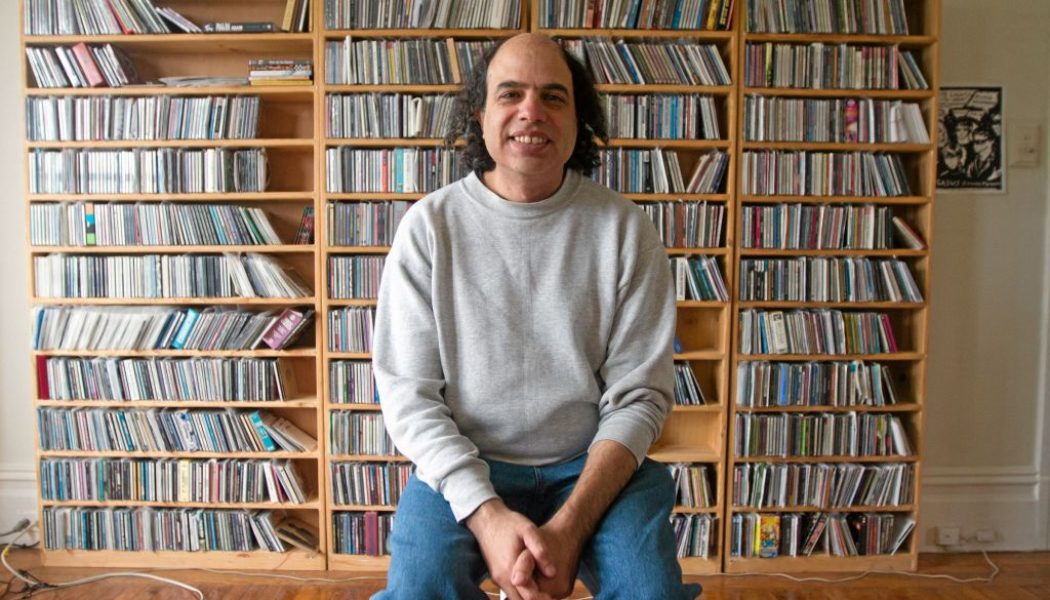

San Francisco-based music historian Richie Unterberger has written more than a dozen books and has taught numerous classes at College of Marin in Kentfield on the history of rock music. He frequently gives presentations at libraries in the Bay Area, accompanied by rare clips and unreleased recordings. On Saturday, Unterberger will present a program on soul music in the 1970s, featuring videos of artists like Nina Simone, Sly Stone, Marvin Gaye, Stevie Wonder and Curtis Mayfield, who pushed the genre in a more intellectually and artistically challenging direction during that decade. Though the focus is largely on African American music, Unterberger will also discuss reggae artists like Jimmy Cliff and Bob Marley, who brought the Afro-diasporic culture of tiny Jamaica to global attention in the ’70s.

The talk will take place at 11 a.m. Saturday at the Novato Library at 1720 Novato Blvd. in Novato.

This presentation is in conjunction with the Novato Library Book Club, whose most recent selection “Another Brooklyn” (Jacqueline Woodson, 2016) focuses on a Black woman growing up in ’70s New York who likely would have been surrounded by music such as this.

Unterberger took some time to explain the significance of his upcoming presentation and why the ‘70s were such a fertile time for soul music.

Q How did you narrow down which artists and videos to show?

A I decided to focus on the ones that showed soul music developing into a more socially conscious form. But it’s not all protest music or songs reflecting the worst conditions of African American life. I have a couple of clips from Wattstax, a major soul music festival that sometimes has been forgotten in relation to the famous rock festivals of the time. Wattstax was a major statement in the heart of a major Black community, Watts (in Los Angeles), that had a negative image in much of the press because of the riots that had happened there. But it was a real community, and (Wattstax) was a celebration not just of soul music but of that Black community.

Q Tell me about the social and political climate that inspired this music.

A I think throughout the ‘60s a greater surge of African American pride had been growing. African Americans had to some degree more social and political power than they had ever experienced in this country, and it wasn’t just through elected officials but also through activist organizations like the Black Panther Party, which, of course, was based in the East Bay and became a national movement. And for the more negative aspects, there are various theories as to why the prevalence of drug use, especially hard drugs, increased in African American urban communities in the ‘70s. But it was definitely there, and it wasn’t just affecting the community as far as addiction. Quite a few young people turned to selling and profiting from drugs, in part I think due to the limited economic opportunities for African Americans and other minorities.

Q The 1970s was an amazingly creative period for soul music. What do you believe inspired this surge of creativity?

A Although soul music of the ‘60s was a great and important form, in the ‘70s it was moving in exciting new directions with the blend of influences from rock — not just sonic influences like Jimi Hendrix and psychedelic rock, but also how music was assembled and packaged. In the 1960s, soul music had been very oriented towards singles. That was starting to change in the mid- to late ‘60s by artists who were considering the album as a total experience and an art form. Songs, even if they weren’t about politics per se, were addressing subjects aside from romance or dancing and partying, which in soul and rock had been the main subjects before the mid-’60s.

Q Is there a particular artist or album you feel exemplifies the artistic and social currents in 1970s soul?

A Personally, I think Curtis Mayfield’s “Superfly” reflects inner-city realities in a really interesting way. There were a lot of what are called “blaxploitation” movies in the ‘70s, and there were quite a few soundtracks — there was Marvin Gaye’s “Trouble Man,” for instance — but “Superfly” is easily the best of those. The movie on the surface is like a shoot-’em-up thing with a bunch of bad guys dealing with guys who aren’t quite as bad. I think the soundtrack tells you what’s really going on, not just in the movie, but with the drug wars and fatalities that were growing in the African American community in the early ‘70s. It’s interesting, too, that the soundtrack ended up being a lot more enduring than the movie. The movie I think is pretty mediocre, but the songs tell you what’s really going on in the inner city beyond some of the more sensational aspects.