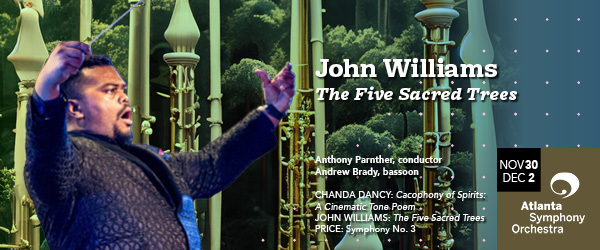

November 30 & December 2, 2023

Atlanta Symphony Hall, Woodruff Arts Center

Atlanta, Georgia – USA

Anthony Parnther, conductor; Andrew Brady, bassoon.

Chanda DANCY: Cacophany of Spirits (2023

John WILLIAMS: The Five Sacred Trees (1995)

Florence PRICE: Symphony No. 3 in C minor (1938)

Mark Gresham | 2 DEC 2023

At the cusp, two weeks on the heels of a program that celebrated African-American women in classical music, the Atlanta Symphony Orchestra presented another program spotlighting African-American musicians and composers, including a world premiere; in fact, none of the repertoire on Thursday evening had ever been previously performed by the ASO.

Guest conductor Anthony Parthner, music director of the San Bernardino Symphony Orchestra in California, opened the concert with the world premiere of Cacophony of Spirits: A Cinematic Tone Poem by Chanda Dancy, an experienced composer of film and television scores who has been working to develop an emerging presence in the concert circuit.

An alumnus of the USC Film Scoring Program and Sundance Composers Lab, Dancy is also a violinist, keyboardist, and vocalist with the indie rock band Modern Time Machine. Among over six dozen items listed in her filmography since 2004, Dancy is known in the film world for her work on the 2022 Sundance Film Festival Award-winning documentary Aftershock (U.S. Documentary Special Jury Award: Impact for Change), the 2020 Netflix TV original miniseries The Defeated (with fellow composer Nathaniel Méchaly), 2022 biopic Whitney Houston: I Wanna Dance with Somebody; the Korean War epic Devotion (2022), and most recently, Lawmen: Bass Reeves, “about the legendary lawman Bass Reeves, one of the greatest frontier heroes and one of the first Black deputy U.S. marshals west of the Mississippi River,” which launched its first season on November 5 — its sixth episode airs this Sunday, December 3, 2023.

Like a sequence of scenes in a film score, over its 12 minutes duration the sectional shifts of moods and emotions in Cacophony of Spirits come across more prominently than its structural description as “a theme and variations in four continuous parts” (“Joy/Winder,” “Fear/Suffering,” “Rage/Destruction,” and “Sorrow/Acceptance”). The piece also hearkens to stylistic elements drawn from Stravinsky (especially the low brass and bass drum parts, derivative of Rite of Spring, in the first segment), Prokofiev, and a handful of 1940s Americana composers; like many film scores, compositionally competent and skillful, but hardly a distinctive, original voice. As such, it will not shift the tectonics of music history. However, the fourth section (“Sorrow/Acceptance”), which felt somewhat divergent from the other three, struck this listener as a potential candidate for effective re-scoring for a mixed chamber-size ensemble.

Compooser Chanda Dancy takes a bow after performance of her “Cacophony of Spirits” by the ASO and guest conductor Anthony Parnther. (credit: Rand Lines)

The theme of music by film composers continued with the central piece of the program, The Five Sacred Trees, a 1995 concerto for bassoon and orchestra by John Williams, whose film score credits are far too extensive and well-known to need reiteration here.

The soloist was Andrew Brady, who became principal bassoon for The Saint Paul Chamber Orchestra in the 2022-23 season after having served previously in the same position with the Atlanta Symphony Orchestra since January 2016.

From the opening unaccompanied bassoon solo (which one could immediately imagine as a flute solo played two octaves lower), Brady was afforded many opportunities for lyrical melodic expression throughout the concerto, although comparatively less emphasis on virtuosity, which rose to the occasion primarily in the two faster movements.

Brady played the concerto with ease and assurance, demonstrating well that the bassoon is far more noble and expressive than the “clown of the orchestra” stereotype taught in shallow music appreciation classes. Bravo to Brady (and his bassoonist colleagues in the orchestra) as sterling advocates for the instrument.

The composer’s typically foolproof orchestration for films, however, curiously felt reticent in its efforts to stay out of the way of the solo bassoon part, an admirable compositional goal; however, Williams’ scoring in this instance made his orchestral colors comparatively dull and atmospheric compared to his film work.

Parnther is also a bassoonist, so for an encore, Brady was joined by him in playing a bassoon duet: the second movement of Mozart’s Sonata for Bassoon and Cello in B-flat major, K. 292/196c, a charming piece, with the cello part played by Parnther on bassoon.

Andrew Brady and Anthony Parnther share a bassoon duet as an encore. (credit: Rand Lines)

Among the symphonies of Florence Price, her Symphony No. 3 takes more risks than the First and Fourth (and presumably the lost Second Symphony), embracing African-American idioms, reflecting the composer’s emotional range from anger to playfulness and her affection for jazz and ragtime.

The dissonant dirge-like introduction sets the tone for the first movement’s formal asymmetry, where the second theme is far more extensively developed than the principal theme. It expresses resentment and anger, depicting the impossibility of remaining undisturbed in a peaceful place and the unhappiness of reality.

The second movement features a pastoral quality and ambiguous jazz moments tinged with whole-tone harmony.

The third movement, titled “Juba,” joyfully explores interlocking syncopations, playing with listener expectations while skillfully integrating African-American musical idioms by incorporating a touch of blues and sophisticated ragtime elements. The “juba” (Haitian: “djouba”) or “hambone” is an African-American style of dance that involves stomping and rhythmic slapping or patting of different body parts (arms, legs, cheeks, etc.).

The fourth movement, labeled “Scherzo: Finale,” deviates from a traditional sonata-allegro form, featuring a pentatonic minor theme that incorporates the G-F-Eb motive that runs through the symphony. Its unusual structure, with plenty of free-wheeling development, defies typical expectations.

Overall, the Third Symphony is marked by eccentricities, reflecting Price’s complex emotional exploration and the unity in the recurring G-F-E♭ motive. In many aspects, it is over-the-top in its expressive means, which came across all too well in this performance. ■

Guest conductor Anthony Parnther leads the ASO in a performance of Florence Price’s “Symphony No. 3.” (credit: Rand Lines)

EXTERNAL LINKS:

Mark Gresham is publisher and principal writer of EarRelevant. he began writing as a music journalist over 30 years ago, but has been a composer of music much longer than that. He was the winner of an ASCAP/Deems Taylor Award for music journalism in 2003.