On a recent Thursday, the school day hadn’t yet started at Burnsville’s Gideon Pond Elementary School. But a long-awaited moment had arrived.

In her music classroom, Becca Buck opened a brown paper envelope. “Here we go!” she said. “Our baby!”

Buck and her co-author Qorsho Hassan, who met as teachers at Gideon Pond, were about to hold their new book—The Rhythm of Somalia: A Collection of Songs, Stories, and Traditions—for the first time.

“OMG,” Qorsho exclaimed, as Buck slid the sunset-orange cover out of the envelope.

The two friends examined their book cover in awe, taking in every detail. They praised the care illustrator Joof Farah had taken in designing a dynamic musical scene. On the cover, a man and a woman dance dhaanto in front of an aqal, or nomadic home. The woman’s hijab and skirt move with her steps. The man’s elbow is slightly cut off by the spiral binding, Buck observed. “We’re going to notice every detail,” she said.

The book began as a master’s thesis for Buck, who was completing her degree in music education. Then her adviser, Karen Howard, suggested she turn the project into a book. Buck and Qorsho teamed up, combining Buck’s music education expertise with Qorsho’s knowledge of Somali language, history, and culture. They began writing the book in the fall of 2019.

To create the book, they asked Somali students and parents to share songs, chants, and games they knew from home. They transcribed the words and musical notation, and provided cultural context and pedagogical tips for using these songs in class. Every song, chant, or game, is accompanied by a personal story from the student who shared it. Interspersed with the text are illustrations showing maps of Somalia, musical instruments, nomadic homes, and camels. And the book is full of context about Somali history, culture, and music.

While they were working on the book, the COVID-19 pandemic shut down schools nationally. Qorsho lost her job at Gideon Pond in budget cuts, and was then named Minnesota Teacher of the Year, both a prestigious honor and a major time commitment. She’s since left teaching altogether, and has moved back to her home state of Ohio where she is helping raise her nephew, writing, and consulting. After a years-long writing and publishing process, some kids who shared their songs and stories while at Gideon Pond are now in high school.

The result is a combination of oral history and ethnomusicology; a cultural preservation resource; and a first-of-its-kind guide for teachers who hope to bring Somali music into their classrooms. The initial print run, from the World Music Initiative of Chicago-based GIA Publications, consists of 400 copies. Many districts and teachers have already ordered copies for classroom use, including in Burnsville and Osseo schools.

Howard, an associate professor of music education at the University of St. Thomas and the series editor for the World Music Initiative, said that local music teachers have been asking her for Somali music resources since she moved to Minnesota nearly a decade ago. But until now, she had nothing to offer them.

“The Somali community was just not represented,” Howard said. This book can help teachers challenge a traditionally Eurocentric model of music education, she said: “to treat Somali music in the U.S. as a form of American music.”

Helping Somali students see themselves in the music curriculum has a particular significance—it’s sometimes a subject area of misunderstandings between parents and teachers. Buck said there is a false notion in music education that Somali students do not listen to music. Qorsho explained that some parents may not understand what is taught in music class, and may not want their children to listen to American pop music that they associate with sex and drugs.

“If parents are choosing to not have their children listen to that, that’s their right,” she said. “But you’ll find in most Somali homes, I would say music-making and/or connecting with songs is the bedrock of our culture, of our identity.”

Central to the book is a collaborative approach to music education: Students and parents contributed the stories and songs they wanted to share.

“A very focal part of this song collection is that you don’t just take from a culture, you actually think of ways to contribute and give back,” Qorsho said. “The fact that our students co-authored the book with us—that’s really magical.”

‘When I think of Somali music, I think more than just a song’

Somalia is known as the “Nation of Poets,” with a rich history of storytelling, poetry, and song. Yet until the 1940s, the Somali language did not have a word for music, which took a secondary role to poetry.

“There’s no direct translation for music in Somali, but there are definitely multiple ways to make music in Somali,” Qorsho said. “At a young age, I knew that poems were a form of music. I knew that chants, buraanbur [poetic dance], a lot of the drumming and the dancing that we would do was music.”

Music has many purposes in Somali culture, Qorsho said: It’s used to process grief and to revitalize. Some songs promoted unification of the Somali territories and decolonization. Many students’ relationship with music is also shaped by learning to chant the Arabic alphabet and memorize the Qur’an, she said.

“When I think of Somali music, I think more than just a song,” Qorsho said. “I think of all the ways in which I learned how to speak Somali.”

Because of the strong oral tradition in Somalia, many songs, games, and chants have been passed down within families but have not been written down. Then, the civil war destroyed many physical cultural artifacts. And some traditions were lost as people fled their home country.

Joof Farah, a Columbus, Ohio–based product designer who illustrated the book, said that he had grown up around many of the games, poems, and dances, but had never seen them written down.

“It was just kind of word-of-mouth before,” he said. “It was something that my siblings taught me. No specific rules that I can point to to determine whether they were playing fair or not.”

He knew the melody of some songs, but as a child he did not always know all the words or cultural context, he said.

“Right now, I’m relatively young, but this is something that I hope to also pass on to my children,” Joof said. “This is a resource that allows me to pass that on.”

‘The music does not stand on its own without these stories’

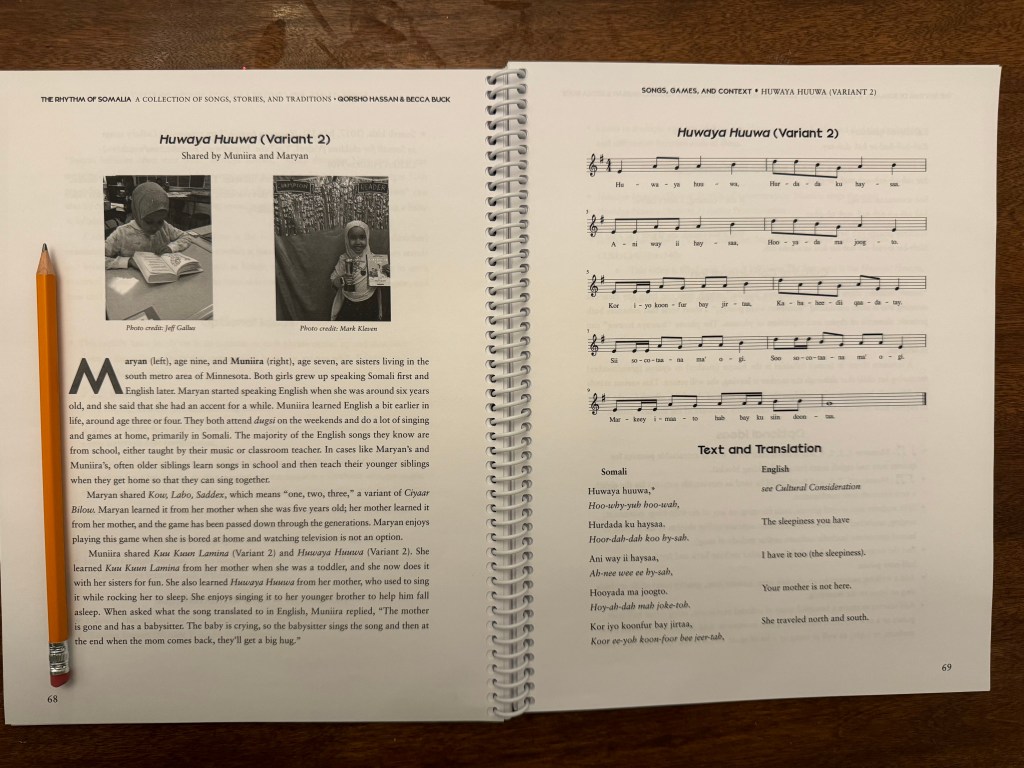

The book brings not only Somali music into the classroom, but also stories from the students and parents who shared their songs, chants, and games. Qorsho and Buck stressed that these stories cannot be separated from the music. They described the students who contributed their songs and stories as the book’s co-authors. Each song or game in the book starts with the story of a child who shared it.

“This gives us a chance to look at who’s sharing a song and why, and what do they want to share with those that are reading and interacting and engaging with this music,” Qorsho said.

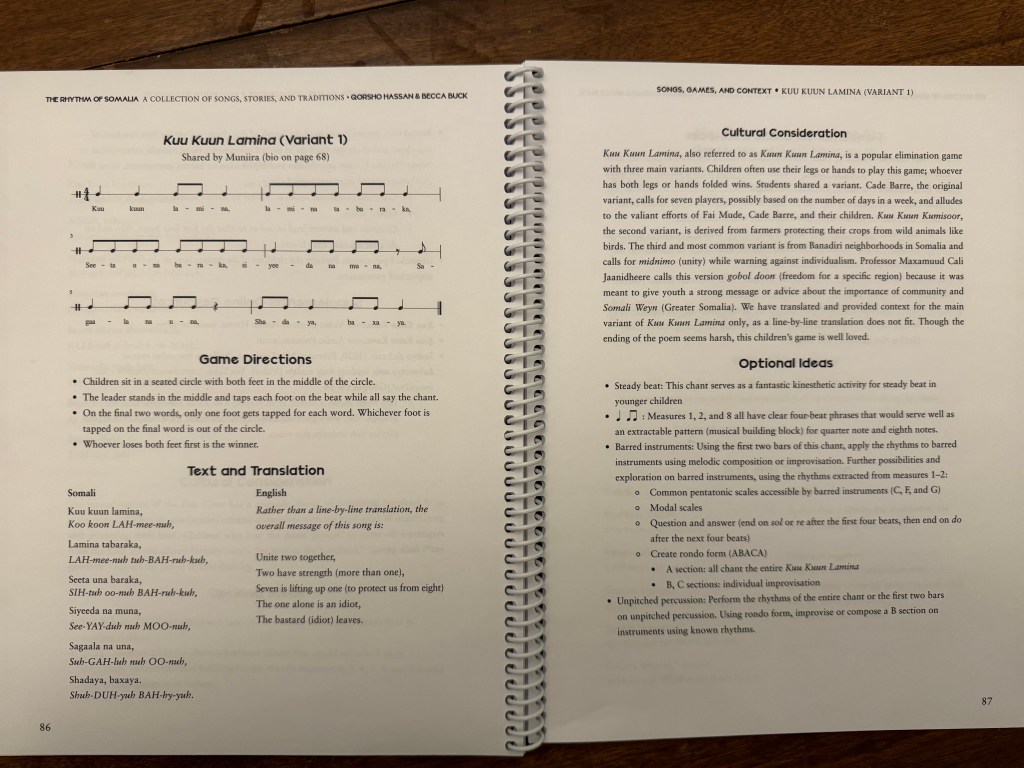

After the student’s story and photo, the book shows musical notation of the song, followed by text and translation, notes on cultural consideration, and optional ideas for class activities—such as discussion topics, rhythm lessons, or suggestions of instruments to add to the vocal music.

Muwahida Hadis, 11, who now attends Nicollet Middle School, was one of the students who shared her story and a song for the book. She contributed the song “Maanta,” a celebratory song that she and her family often sing on Eid, in the car on the way to prayers.

Muwahida said she first heard about the book because “all my friends were in it.” She wanted to participate, she said, “so I can share my life with other people.”

An avid reader, Muwahida said that having her own name and photo in a book was “the most amazing gift.” And what would she do when she received her copy of the book? “Oh, I’m putting that in a frame,” she said.

Sharing songs with other people can help them know they are not alone, she said. She hopes to read the book to her little cousins. “I want them to know that we’re always recognized,” she said.

Amina Hussein helped her daughter, Nashaad, make sure she had the right words to the songs and games she shared for the book.

“Those are the songs my mom used to sing,” Amina said. “Seeing my daughter be part of that book, my Somali culture traditions, all the songs—it was a great deal for me.”

Amina grew up in Kenya; Nashaad was born in America. Watching her American-born daughter share the same songs and games she played growing up was a “privilege,” she said.

Amina runs an autism center in Burnsville. She hopes that singing Somali lullabies may be beneficial to her clients, just as they have helped her son, a special education student. Often, when her clients hear a song, they sing along, she said.

“At least they will know some songs from the Somali culture,” she said. “Like a sense of identity.”

‘A labor of love and community-building’

Harbi Mohamed Kahiye, a Minneapolis-based percussionist and keyboardist who performs often with the Cedar Cultural Center, told Sahan Journal he was “ecstatic” about the book. He has often presented about Somali music at schools and universities.

He said he had recently returned from a residency in St. Cloud where he taught fifth-graders how to play the drums, make beats, and perform traditional Somali dances such as dhaanto and buraanbur. He also taught them songs that Somali students and teachers used to sing. “It was very empowering for them,” he said.

Qorsho and Buck hope the book gives students a sense of empowerment and ownership over their education. Since they started their song-collecting process, they have presented at music conferences. Some teachers already have started incorporating the material into their classes: adapting the lullaby “Huwaya Huuwa” for a choral setting, and playing the foot-tapping game “Kuu Kuun Lamina” with their students. “Music teachers are very amped about it,” Buck said.

Teachers tell her their students light up when they introduce this material to her class, Buck said. She’s seen that with her own students, too. One parent, who also worked at the school, teared up when she saw Buck teaching “Kuu Kuun Lamina.”

Buck emphasizes to music teacher colleagues that they should give students room to talk about their own experiences, because they may know a different variant of a song or game. Teachers often worry about cultural appropriation, she said. But they can avoid it if they share historical context for the songs, and provide space for students and families to share their expertise. The book provides detailed instruction for how to present the material thoughtfully.

“What I really hope that they do is share the stories and share the recordings with their students, and talk about the culture,” Buck said.

For Qorsho, the most meaningful part of the project was the student and family engagement. She’d like to see more educators draw on the expertise of their students and parents, to create classrooms where students feel they can promote understanding of their own culture, and feel safe to make mistakes.

“It’s a labor of love and community-building that I think can be applied to any school across the nation,” Qorsho said. “It’s not just about Somali culture. I think it could be about all cultures.”

You can order “The Rhythm of Somalia” here.

“The Rhythm of Somalia” Book Launch

WHEN: Saturday, December 9, 2023, 3–6 p.m. Program at 4:15

WHERE: Gideon Pond Elementary School, 613 E 130th Street, Burnsville, MN 55337

WHAT: Celebration with Somali traditions and food honoring the contributors to the book

WHO: Hosted by Qorsho Hassan, Becca Buck, Joof Farah, and Karen Howard

RSVP: At this link

Amina Isir Musa contributed reporting.