Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Luxury ecommerce platform Farfetch won approval from the European Commission last month to complete its acquisition of a large stake in rival Yoox Net-a-Porter, more than a year after the deal was announced.

As a result Farfetch, which acts as an online platform for more than 1,400 boutiques that sell high-end brands including Alexander McQueen, Gucci and Prada, will be able to sell the brands of Swiss luxury group Richemont, Yoox Net-a-Porter’s other owner.

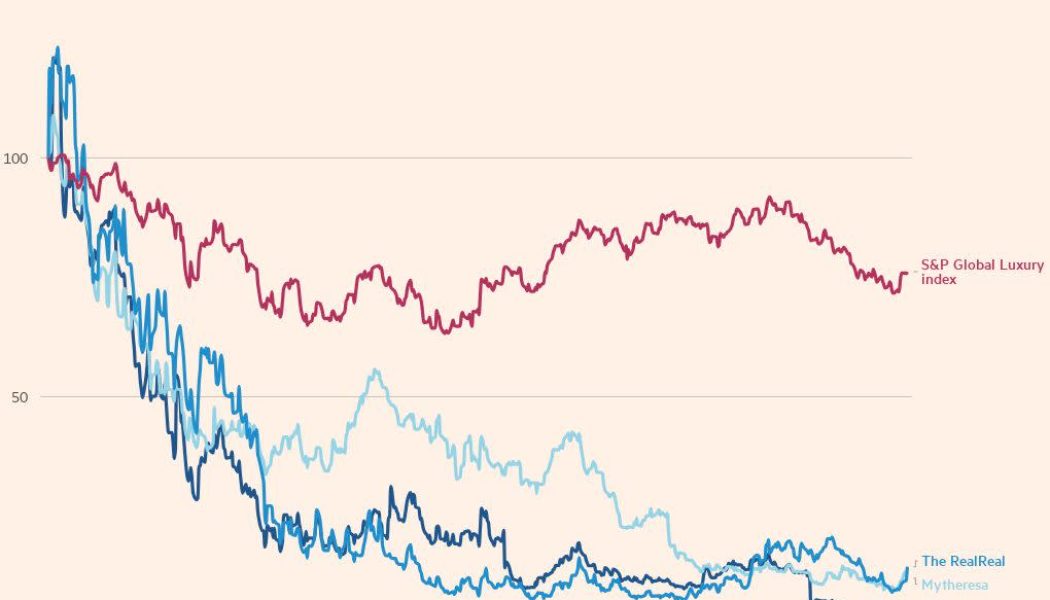

It is a rare bit of good news for the New York-listed marketplace that floated in 2018. Farfetch shares have slumped about 98 per cent since their 2021 peak, its market capitalisation crashing from about $26bn to less than $600mn today.

Luca Solca, a luxury analyst at Bernstein, has long been critical of the company, accusing it of burning cash in the hopes of becoming, in his words, the “Uber of luxury”.

“Companies like Farfetch have been dispersing their resources and increasing their costs on too many different fronts,” he said.

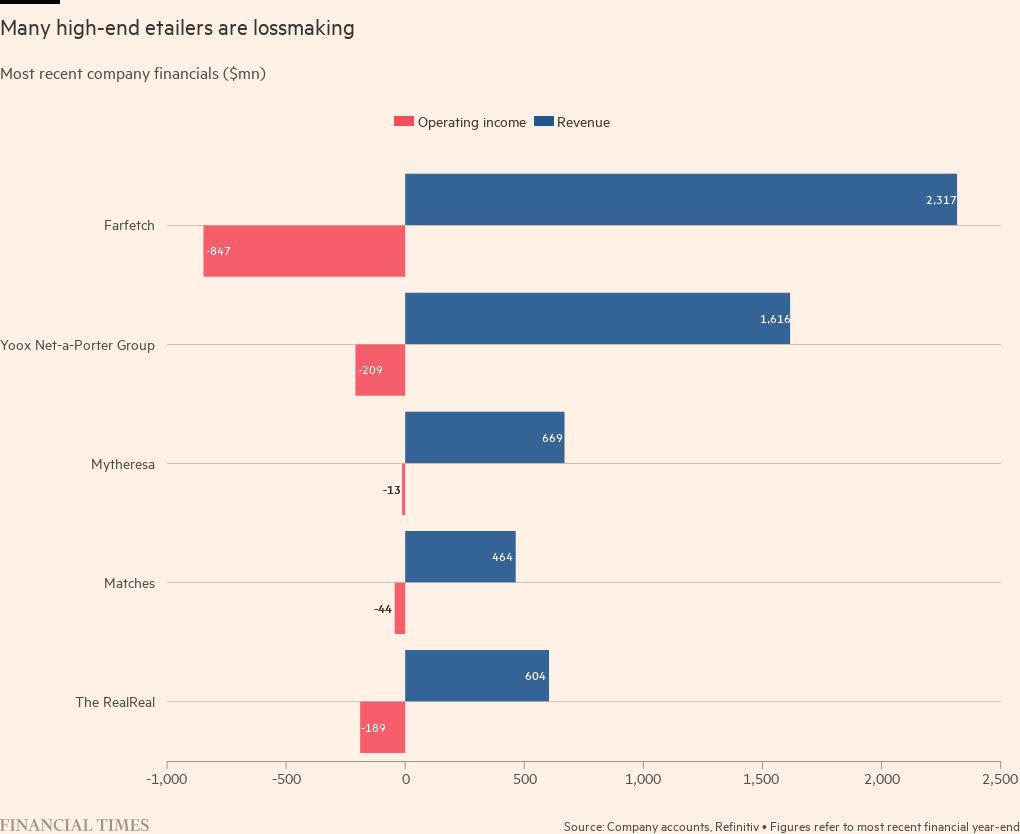

Farfetch, which did not respond to a request for comment, is not the only luxury ecommerce group to be struggling.

Yoox Net-a-Porter, which operates online stores Yoox, Net-a-Porter and Mr Porter, reported a net loss of €541mn in the year to March. Richemont has taken €3.4bn non-cash writedowns previously on the company; it announced an additional €500mn non-cash writedown when it reported results on Friday.

Matches, a London-based high-end ecommerce company, secured a £60mn support package from its owner Apax Partners after reporting widening pre-tax losses of almost £39mn for the year ending January 2022.

Lyst, a fashion search engine that lists brands such as Gucci and Tory Burch, cut 25 per cent of its staff last year while resale platform The RealReal has begun a turnaround plan under a new chief executive.

Shares in smaller Munich-based operator Mytheresa have fallen about 65 per cent over the past 12 months. It posted a €15.1mn net loss in the year to June 30.

Others are cutting costs in anticipation of tougher times ahead. SSENSE, a Canadian company that targets younger shoppers and was valued at $3.6bn in 2021, dismissed 7 per cent of its workforce this year.

The waning fortunes of ecommerce groups partly reflects a tougher environment post-coronavirus as the luxury and ecommerce sectors cool. However it also points to the increasing digital heft of the luxury or high-end brands that make the products.

“Covid heavily accelerated the technological catch-up of luxury companies, in both the interfaces and the customer experience but also logistics — making more product available for the online platform,” said Claudia D’Arpizio, head of luxury goods at Bain & Company.

She added that many were now using digital tools such as apps to cultivate closer relationships with top-spending customers and offer them personal shopping or home delivery services.

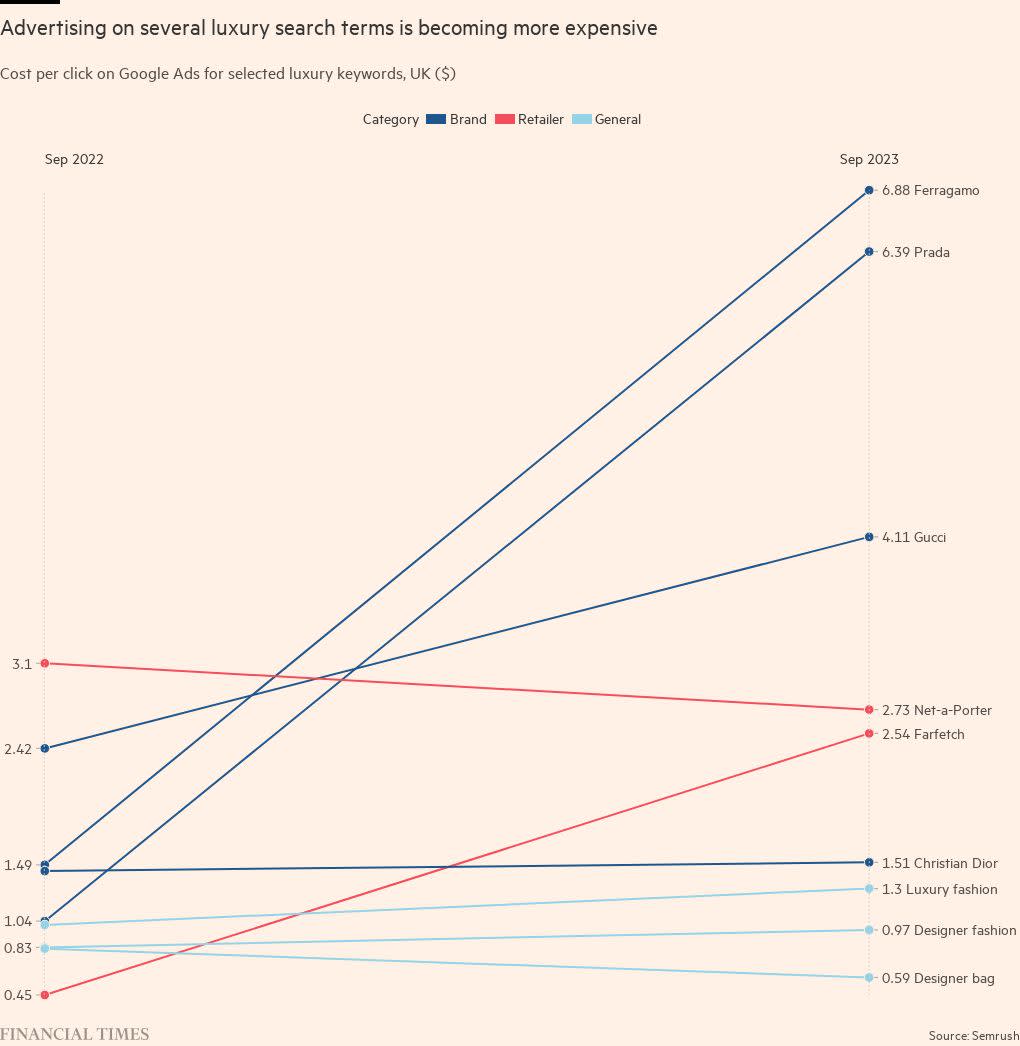

Increased competition for high-end ecommerce has affected the cost of online advertising, which is vital for the sites to attract customers.

Data from Semrush showed the cost per click for several luxury-related search terms has shot up over the past year.

At the same time, the wholesale model used by many multi-brand retailers is coming under strain. As overall demand cools, luxury groups are increasingly trying to reduce the number of discounts offered on their products and control how their brands are represented online, said D’Arpizio.

Kering, for example, reported a 29 per cent year-on-year drop in wholesale revenue for its luxury brands in the third quarter of this year, as part of its efforts to “tighten its control over distribution”.

To offset this, Net-a-Porter and Matches have in the past couple of years started offering e-concession models — which allow designer labels to operate their own storefronts — alongside wholesale. While more appealing to brands, it does reduce the retailers’ margins.

Farfetch’s white label product, which provides ecommerce technology, is a small but promising part of its business, according to analysts at Wells Fargo.

Others are looking to capitalise on the popularity of discount luxury and second-hand. Yoox Net-a-Porter owns The Outnet, which sells last season’s styles at discounted prices, while Matches Outlet launched last month with 6,000 items at up to 70 per cent off.

Web traffic data indicated that focusing on a more selective edit of styles and brands, as SSENSE does, may also help retailers stand out from the crowd.

D’Arpizio believed that multi-brand ecommerce sites would continue to play an important role in the market. Unlike brands’ own websites, they allow shoppers to mix-and-match items, browse curated collections and discover new labels.

But she expected to see more consolidation. “Many of these companies have had very high valuations for their growth trajectories,” she said. “At a certain point, they will need to find the right formula to be profitable and sustainable in the long run.”