The exorbitant cost of luxury fashion has left us out in the cold, wondering who can sustain this market?

Historically, luxury fashion brands have enjoyed strong pricing power, meaning that they can apply considerable increases without necessarily losing customers. But in 2023, price tags hit eye-watering highs — and there has been no sign of the trend slowing.

According to the data company EDITED, average luxury prices are up by 25 percent since 2019. Many brands attribute their increases to everything from inflation and the balancing out of regional price disparities to the fallout of the pandemic and impact of the war in Ukraine. But for many luxury fashion brands, the uptick has been taking place over a longer timeline.

Take Chanel, where handbag prices have more than doubled since 2016. The auction house Sotheby’s found a classic 2.55 Chanel bag sold for around $1,650 in 2008. In 2023, that figure from Chanel is closer to $10,200. (If the cost had risen in line with inflation over the 15-year period, it would be expected to cost $2,359). This week, Pharrell Williams, the men’s creative director at Vuitton, unveiled the label’s new Millionaire Speedy Bag. The crocodile hide bag is made-to-order, costs a cool million and has a distinctly Scrooge McDuck aura.

“Industrywide, the pricing has gotten truly absurd,” the influencer Bryan Yambao noted in an Instagram post this week when discussing a $6,000 woolen Miu Miu coat. “I do think this is a good time for most brands to lower their prices.”

In the past year there have been signs that so-called aspirational customers, who buy entry-level luxury products like cosmetics and spirits, have curbed their spending. Middle class professionals who once saved up for a luxury investment handbag or coat have been aggressively priced out.

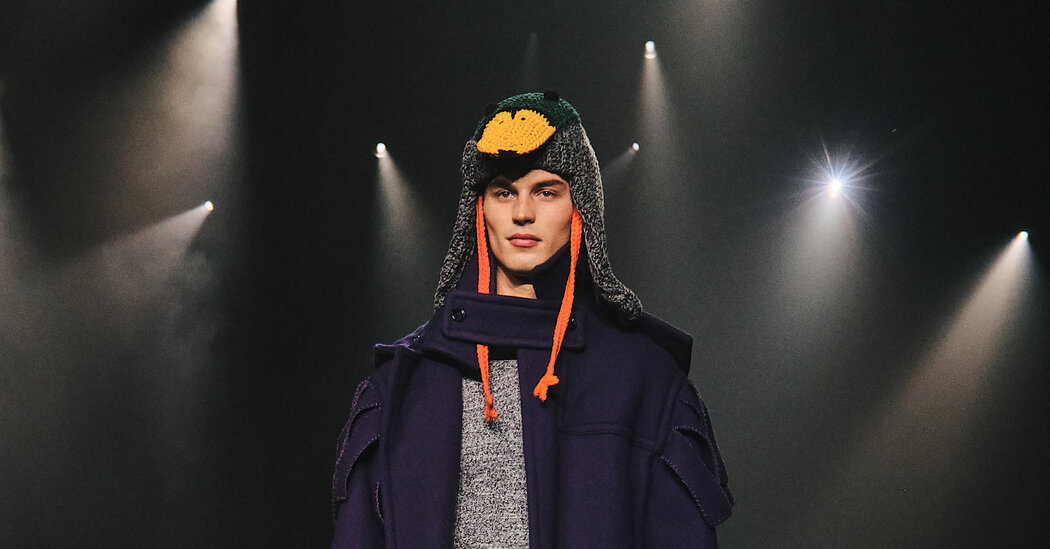

So who is spending $3,000 on a knit hat shaped like a duck from the British brand Burberry? What about $24,500 on a vicuña jacket by Brunello Cucinelli? Or $1,250 on a white cotton shirt by The Row?

The answer is the 1 percent, obviously (or those willing to incur credit card debt). Luca Solca, an analyst for Bernstein, estimates that the top 5 percent of luxury clients now account for more than 40 percent of sales for most luxury goods brands. As wealth inequality increases globally, luxury brands are doubling down on an ever smaller slice of their clientele. Will this strategy work? Or is there a backlash brewing which might force the luxury pricing bubble to burst?

The below discussion among Style journalists has been edited and condensed.

Elizabeth Paton To many people, luxury price tags have always been absurd and almost amoral. And prices in luxury fashion keep going up, and up, and up. Does it matter to customers?

Vanessa Friedman The high prices of Phoebe Philo’s new line certainly struck a nerve, despite the fact they are actually at the lower end of the luxury market. It made me wonder why it was the Philo line that sparked such outrage.

Stella Bugbee It’s rare to see a collection for the first time and be simultaneously confronted by the prices. We go to fashion shows and admire or critique them on a conceptual level, but often what we see on the runway doesn’t make it to the store. It was also more expensive than the old Celine.

VF Although, almost everything “luxury” (including new Celine) is now more expensive than old Celine. Also, perhaps, because Phoebe has become such a mythic, fashion-savior-of-women, rightly or wrongly, and we were waiting for years for her line, a fantasy arose in which she also saved more women by making her clothes available to more people. For some of her fans these prices almost seem like a betrayal.

EP The balance between accessibility and exclusivity has always been a tricky one for luxury fashion brands, especially as the sector expanded into new markets. Now, many people who might have treated themselves with a bag are tightening their belts.

VF Well, the 1 percent are the target market for high fashion. The rest of us are left with perfume and lipstick.

EP Right, but a certain type of professional used to feel like they could save for a special piece. A Burberry raincoat. A Gucci handbag. Those are out of range for nearly everyone now.

Guy Trebay Don’t forget about credit card debt, which the Federal Reserve currently pegs at over $1 trillion.

SB The resale economy has also changed the calculus. You can get all of those things secondhand, not long after they sell for full price.

EP And if they are hot enough items, they can sell for even more than full price! Like an Hermès Birkin for example.

VF There’s a sort of warring imperative here between people who see it as a badge of honor not to buy full price and those who belong to the very tiny club that can. Economics are involved, but as much as anything, it’s also psychology.

EP Resale is also a good barometer for whether pricing strategies are working. Chanel and Hermès drive the top of the resale market. More trend-driven high-fashion houses — who have been raising their prices — don’t fare so well. If there is a market correction, it will be more directed toward brands where people take a loss on products they want to sell on the secondary market.

Jessica Testa I know of at least one resale website, the Paris-based ReSee, where Philo-era Celine is the third most popular brand, below Chanel and Hermès. And there are several independent sellers on Instagram dedicated exclusively to selling Philo-era Celine designs, fetching prices above what they cost at retail 10 years ago. There are people who spend years hunting eBay for one specific product in their size.

VF Which brings me back to Phoebe Philo’s current scarcity model: We don’t even know how much of any piece they produced (the company wouldn’t say) but the message is the market will bear the prices, since the products are sold out. We think because it is more expensive, it has more value.

GT This is the stuff for which Daniel Kahneman won the Nobel. Subjects shown two identical cashmere sweaters, one at a far higher price, inevitably chose the more costly of the two. His point was that we don’t think. We act irrationally.

VF I go back to the idea of betrayal. Because so many women relate to Phoebe Philo as a person, or at least the idea of Phoebe and what her work once represented, they felt excluded or ill-served by the pricing of her new line. They cared deeply about what she was going to make, and then it seemed as if she didn’t really care at all about including them.

EP Also that Phoebe — and the powers that be in luxury — spent a considerable period courting aspirational audiences. It’s just now they’re pulling the drawbridge up. Fashion is always at risk of looking out of touch with the wider world, and certain items that seem to have gone viral on social in recent months — like the Burberry duck hat — triggered particular wrath, more so than usual.

VF Burberry is also selling a $21,000 viscose dress with a Burberry knight riding across the front.

GT Better at that point to pin dollar bills to your chest.

EP Speaking of dollars, a quarter of a trillion them have been wiped off the value of Europe’s seven biggest luxury businesses since April, and sales are generally down across most fashion groups. That is the aspirational middle class stepping away from the credit card machine.

JT My pet peeve is when high-end brands collaborate with mass-market brands and yet the pricing doesn’t even meet in the middle — it’s still $900.

EP Like the recent Banana Republic collaboration with Peter Do.

GT And that’s relatively new. By contrast, there were the wonderful and completely affordable collabs Jil Sander, Tomas Maier and others did with Uniqlo.

JT Guy Trebay may have complimented my Clare Waight Keller Uniqlo bag a mere two days ago, folks.

EP The collabs do occasionally have some treasures!

VF In a sense they give the luxury brands an excuse for their pricing, because they can say, “Well, but we did this or that mass market collab.”

EP I agree and I don’t think we will see this approach by the luxury powers changing anytime soon. The bubble doesn’t seem to be bursting — yet.