Vacationing during the off-season has long been considered a cost-saving boon. But can families with school-aged children take advantage? Should they?

For her family vacation next year, Liz Thimm has booked a 10-day trip to Bocas del Toro, Panama, in February. She requested time off from her pharmacist job a year in advance, checked out guidebooks from the library and has shared itinerary ideas with her daughter and son — who are 11 and 9 — to involve them in the planning process. One thing she has not and will not do? Schedule the trip around a school vacation.

Much of Ms. Thimm’s approach to planning comes from the high costs and time constraints endured during a spring-break vacation the family, who lives in Wauwatosa, Wis., took to Puerto Rico in 2019.

“We paid $2,260 for four seats, had a six-hour layover on the way there and a 2:15 a.m. departure on the way home,” she said. “And those were the cheapest tickets we could find.”

Taking a trip during the off-season traditionally offers travelers fewer crowds and reduced fares and has long been considered a boon for budget-conscious planners. This trend is all the more pressing as the appeal of a traditional summer vacation has diminished, particularly after this year’s hot, crowded, expensive and natural–disaster–filled season.

But can families with school-aged children take advantage? While tacking on a day or two before or after winter and spring break has been a relatively normal occurrence for some families, now some well-off parents, emboldened by the rise of remote work and schooling in the pandemic and fed up with the record-breaking high prices of peak-season travel, are saying yes.

“People are feeling more freedom to be flexible,” said Natalie Kurtzman, a travel adviser with Fora Travel in Boston, noting that many of her clients with families are increasingly comfortable extending school breaks, and skipping a few days of classes in the process, to avoid high airfare prices that tend to appear during vacation periods.

“You can see that parents are becoming more and more brazen about doing it,” said Karen Rosenblum, the founder of the Spain Less Traveled travel agency.

But teachers and school administrators worry about ramifications, like students falling behind in schoolwork, and the mixed messages that the practice of skipping school might send.

“I feel like education is a privilege, and some students see it as a burden,” said Joanne Davi, a middle school teacher at St. Peter Martyr School in Pittsburg, Calif., who has noticed a major uptick in students missing school to travel since the pandemic. “When you make choices over school, that often translates to how students make choices during the day.”

More travel year-round for all

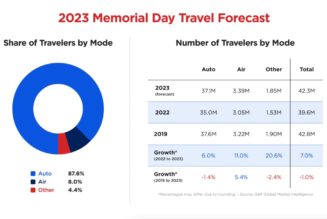

Not all families in the United States are ditching school. This year, in its U.S. Family Travel Survey, the Family Travel Association noted that summer and spring vacations remain the most popular times for families planning trips. But 56 percent of respondents found the timing of school breaks to be a challenge, and 59 percent cited affordability as their most pressing issue.

Travel costs are just one part of the financial equation, of course. Since the pandemic, many Americans have been struggling to keep up with a rising cost of living. Persistent inflation has led to changes in spending behavior, including, for some, around travel.

“Affordability has always been the most challenging thing. We’ve seen that since the survey began in 2015,” said Lynn Minnaert, a professor at Edinburgh Napier University in Scotland and co-author of the 2023 Family Travel Association study. “But now, prices are the highest I’ve ever seen them. Being able to travel off-season would make a big difference for many families.”

Anecdotally, at least, a desire for scheduling flexibility is taking root. Melissa Verboon started the Facebook group Travel With Kids in 2017 and writes a blog covering her family’s travel; she said that the group’s membership had grown since the pandemic, with more conversations centering on traveling during the school year. Ms. Verboon, who lives in Holiday, Fla., and has four kids (15, 13, 11 and 9), believes that family time at home during the pandemic was a major impetus for reimagining vacation scheduling, as well as reimagining the types of trips that parents could take with their children.

Stephanie Tolk voiced similar thoughts. Ms. Tolk currently lives in Portland, Ore., but in 2021 and 2022, traveled internationally with her husband and two daughters for more than a year.

“People had bought into the idea that their kids went to school at 8:15 and that you don’t see them again until 4 in the afternoon. That was all shattered in 2020,” she said. “I found that I wanted more time with my kids.”

Easier with younger children

For parents eager to travel with their offspring year-round, a prepandemic truth remains: It’s significantly easier with younger, grade school children who have fewer academic, extracurricular and social demands. Ms. Thimm, whose daughter started middle school this year, has discovered that school-year travel planning is more challenging.

“I’m getting a little more nervous about taking her out, and she doesn’t want to miss out on anything that’s going on in school,” she said.

Alison McMaster, a travel adviser and corporate travel planner who lives outside Boston, has been traveling with her two sons, now 11 and 13, during the school year since they were young, sometimes tacking on extra days or weeks to school breaks. The family has even spent close to a month in destinations like Peru, Colombia and Europe.

“The education that they’re going to receive by way of international travel and cultural experiences outweigh days missed in the classroom,” she said. “The best version of my kids is when we are traveling.”

She’s unsure, however, if she’ll be able to pull off an extended trip this year.

“As they’ve gotten older, it’s become more important for them to be physically present in school,” she said of the shift from elementary school. The upper schools require more work and holding students more accountable. “There’s a sort of unspoken pressure,” she said

Ms. McMaster’s sons attend a private school, which has been generally accepting of their absences, extra work and increased accountability aside. But public elementary and secondary school systems, which educate about 50 million students, or about 88 percent of U.S. schoolchildren, have varying levels of tolerance for missed days of school. In recent years, they have also been contending with a rash of absences, travel-related or not, and plunging test scores among their students.

In Ms. Thimm’s Wisconsin school district, families may receive a letter from the school district requiring a meeting between the parents and school staff, should a child miss more than 10 days of classes.

“We’ve never gotten a letter; my kids are both great students and we usually only pull them out for five to seven days,” she said. “But last year, my son had Covid and he was out for five days because of that. I was definitely stressed about a trip we had planned, knowing that he couldn’t get sick again and miss any more school.”

In Ms. Davi’s school in California, a student missed the first three weeks of classes this year for a trip. Others have traveled to Las Vegas, Disneyland and Washington, D.C. The school’s policy allows these absences, so long as the administration is informed beforehand, but teachers are not obligated to put together work packets for children missing class for vacation.

“I tell the students, ‘We continue without you, so the responsibility is on you when you get back,’” Ms. Davi said, adding that classroom work and other assignments are online on Google Classroom. Whether or not a student will check in and keep up is “case by case.”

“There are some students who are intrinsically motivated as it is,” she said. “But then, there are students who are completely cut off. They come back and have no idea what’s going on.”

Out of the classroom, out in the world

For some parents, the incompatibility of school schedules with travel desires leads families to drop out of school systems altogether, at least for a little bit.

“Worldschooling,” a loose term that refers to making travel a central part of a child’s educational experience, can involve a monthlong trip to Europe, or years spent traveling. Parents might try to stick to the curriculum of a school back home using workbooks and remote learning tools, or choose to engage in more free-form, interest-driven learning.

Ms. Tolk worldschooled her daughters during their years on the road. The girls were 10 and 12 when they left, and while she and her husband initially tried to stick to a semi-strict schedule — daily math lessons, grammar exercises and spelling lists — they quickly found themselves easing up, focusing instead on the places they were exploring.

“We ended up doing a lot of family projects. All four of us would research something we were interested in and present it to each other,” she said. While they were in Egypt, one daughter did a project about ancient makeup traditions in Egypt, while another delved into the story of the wife of King Tutankhamen.

Though there has long been a small community of families who travel with their children, Ms. Tolk believes that the pandemic and social media have both made worldschooling a more approachable option. She is currently working to set up three worldschooling hubs through her company, Deliberate Detour, where families can meet up for learning and socializing, in Peru, Guatemala and Mexico.

Meanwhile, her daughters, now 12 and 14, are adjusting to attending public middle school in Portland, which has been challenging. The day feels long and overly structured, while other students strike the girls as closed-off. The jury’s still out on how they’ll fare academically, though so far, they are finding the work easy, said Ms. Tolk. Still, the value of these trips remains incomparable for her family.

“I’ve had a life of really impactful, powerful, transformative international experiences,” Ms. Tolk said. “I always knew that I wanted that for my children.”

Follow New York Times Travel on Instagram and sign up for our weekly Travel Dispatch newsletter to get expert tips on traveling smarter and inspiration for your next vacation. Dreaming up a future getaway or just armchair traveling? Check out our 52 Places to Go in 2023.