Once when Sufjan Stevens was in college, he brought an injured crow to the biology lab to help save its life. “You are doing the universe a great favor,” a woman who ran an animal sanctuary told him once he called her to the scene. This is one of several stories Stevens tells in his 10-part essay included in the elaborate physical edition of his latest album, Javelin, all in service of exploring his ever-expanding definition of “love.” He writes in an inquisitive and self-aware tone, joking about how that experience with the crow provided “endless fodder” for his collegiate creative writing: “So much meaning, so little time,” he reflects. But if a young Sufjan once sought these encounters for their symbolic potential, the present-day writer of this essay, and of these songs, tells a more pressing story: even more meaning, even less time.

Over and over again on Javelin, Stevens contemplates the end. Sometimes his language, along with the hushed longing of his voice and the romantic sweep of his largely acoustic instrumentation, points toward the demise of a very long relationship. “I will always love you/But I cannot look at you,” he explains, tracing the broken logic governing the loss. “It’s a terrible thought to have and hold,” he admits after wishing ill to someone he once held dear. “Will anybody ever love me?” he asks in the aftermath.

Instantly, the songwriting feels as raw and direct as ever. And indeed, Javelin is Stevens’ first proper album in a long time that seems designed with no grand concept to unify the material or inspire theatrical adaptations; no autobiographical insight to make you reconsider everything you thought you knew about him; no jarring musical change-ups to remind you he is a proud member of the Beyhive. Running under 45 minutes, Javelin begins with a deliberate inhale and ends with a cover of a deep cut from Neil Young’s best-selling album—a track that Stevens manages to make sound even sweeter and more hopeful than the 1972 original.

Like much of his defining work, Stevens wrote, recorded, and produced Javelin almost entirely alone, minus a few key appearances: some guitar from the National’s Bryce Dessner in the dazzling eight-minute “Shit Talk,” and frequent vocal accompaniment from a small choir that includes Megan Lui, Hannah Cohen, Pauline Delassus, Nedelle Torrisi, and the activist and writer adrienne maree brown. It’s got at least one song that instantly joins the ranks of his very best (“Will Anybody Ever Love Me?”) and plenty that draw direct lines to previous high-water marks, both thematically and musically. Centering the devotional melodies and heart-tugging intimacy that characterized his early masterpieces, it’s the type of record, two decades into an artist’s career, that tends to be called a “return-to-form,” suggesting an embrace of his strengths and a diminished instinct to surprise or provoke.

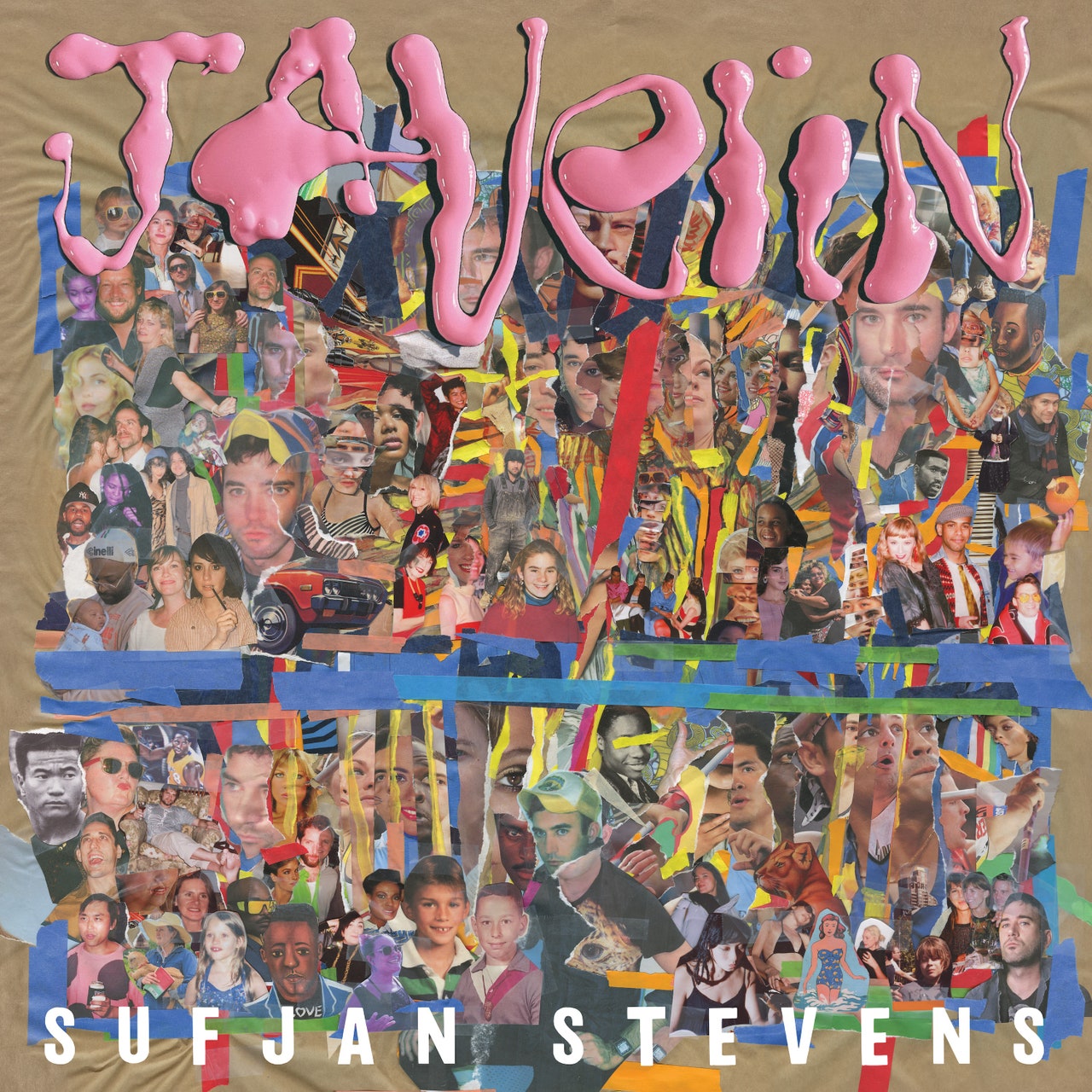

But is anything ever so easy? The intricacy of Javelin is central to the essays and art accompanying the album: collages that overflow with faces of friends and family and heroes, paintings whose colors seem intended to combat Seasonal Affective Disorder. Many songs follow the path of these maximalist projects, beginning with gentle fingerpicking or piano before fireworking into electronic symphonies, orchestral crescendos, and choral rounds. The cumulative effect suggests that, while each story might begin as a stark, personal inquiry, Stevens strives to lead us somewhere divine, an altitude where our lives might appear more beautiful and still.

It is through these trajectories that Javelin, despite its tone of endless searching, becomes one of Stevens’ most uplifting records. In “Should Have Known Better,” a sudden burst of Casio keyboards accompanied an optimistic glance to the next generation—a rare bright spot on 2015’s grief-stricken Carrie & Lowell; Javelin is filled with these kinds of turns. With the notable exception of “Shit Talk,” which dissolves into a long ambient coda that lingers like fog after heavy rain, each song ends somewhere brighter, fuller, and lusher than it began. “So You Are Tired,” which includes Stevens’ most heartbreaking set of lyrics since Carrie & Lowell, climaxes with a lapping wordless refrain from the choir. As his words zoom in closer to a separation (“So you are tired… of even my kiss”), the soothing, major-key resolution suggests an elemental sense of peace, leading to a blend of emotions that feels entirely new within his songbook.

If there is anything Stevens learned from his last proper solo album, 2020’s pared-down synth-opus The Ascension, it is to tell these complex stories in simple ways. Take, for example, “My Red Little Fox,” a love song cast in waltz time, where Stevens uses one of his most classically beautiful melodies to express a series of escalating refrains: “Kiss me with the fire of gods,” he sings, then, “Kiss me like the wind,” and eventually, “Kiss me from within.” Here is the story of Javelin in miniature: The first two are seductions, spoken from person to person; the last is more like a prayer. If the lyrics on Javelin lack the proper-noun touchstones of Stevens’ story-songs, these ones gain authority from an intrinsic sense of self and place. They are approachable like pop songs, but delivered with the same precision as his folk confessionals. They break our hearts from within.

“I know I’ve often been the poster child of pain, loss, and loneliness,” Stevens recently wrote to his fans. “But the past month has renewed my hope in humanity.” He was referring to his ongoing treatment for Guillain-Barré syndrome, a rare auto-immune disorder that left him learning to walk again after losing feeling and mobility in his hands, arms, and legs. In the lead-up to Javelin, he has taken to Tumblr—long his preferred method of communication—to give frequent updates on his recovery. Sometimes he finds humor in the situation—a post about his dream wheels, the “Porsche 911 of wheelchairs”—and sometimes his words are more troubling (“Woke up feeling trapped”). But nearly every post ends with a positive affirmation, or at least a sign-off with a series of X’s and O’s.

This is the tone that Stevens now favors, something familiar and close, where the stakes are high and his sense of empathy is pervasive. This tenderness is partially how “Will Anybody Ever Love Me?,” with its Morrissey-level self-deprecation and whispered instructions to “pledge allegiance to my burning heart,” manages to feel less like a breakdown and more like time-lapse footage of a flower turning toward the sun. Throughout his career, Stevens has used the language of love songs to express religious devotion, and vice versa. Across Javelin, he seems intent on understanding and being understood, with the purpose of exposing the common thread between his pet subjects: raising the endless questions that lead us to seek meaning in one another, and rejoicing in the euphoria of sometimes finding it. And if it sounds like he is occasionally singing to us from rock bottom, it’s only so we can witness the steady ascent onward.

All products featured on Pitchfork are independently selected by our editors. However, when you buy something through our retail links, we may earn an affiliate commission.