In July, I attended a community meeting at the Broadway Armory in Edgewater about the city’s plan to turn the Park District facility into a temporary shelter for asylum seekers. A group of protesters, angry that much of the armory’s programming would be relocated or otherwise disrupted, carried bright yellow signs reading “Don’t Displace Us.”

No matter your grievance, you shouldn’t style yourself as “displaced” by migrants with nowhere to live if you’re going home to sleep in your own bed. But let’s leave that lousy messaging aside. Xenophobic protests like this are fueled by fear that anything given to someone else will be taken from us. And that fear is reasonable, unfortunately, because America’s ultrawealthy have bought themselves a society where we’ll brutalize each other for crumbs rather than confront their staggeringly immoral hoarding of resources.

Take capitalism out of the picture, in other words, and all we’d see arriving on those buses would be new neighbors. But if there’s one thing the rich and powerful have always hated, it’s ordinary people who understand their kinship across categories and borders.

In case you were wondering what this has to do with the World Music Festival, there it is: music brings people from different countries and cultures together, and this festival lets you participate in that process firsthand. No other event gives so many of Chicago’s diverse populations the joy of a concert that says “home.”

World Music Festival Chicago

Full schedule below. Produced by the city’s Department of Cultural Affairs and Special Events (DCASE). Friday, September 22, through Sunday, October 1, various times and venues, all concerts free, many all ages

Download the print version of this guide as a PDF.

Founded in 1999, World Music Festival Chicago is produced by the city’s Department of Cultural Affairs and Special Events (DCASE), with Carlos Cuauhtémoc Tortolero and David Chavez as lead programmers and Brian Keigher of People of Rhythm partnering with Tortolero on Ragamala, the dusk-till-dawn extravaganza of Indian classical music that’s been part of every fest since 2013.

The 2023 festival runs from Friday, September 22, through Sunday, October 1, with 11 events at 11 venues. Nobody fences off a public park, you don’t have to deal with a crowd bigger than the population of Waukegan, and every concert is free.

This guide to the festival includes descriptions of every act (except the three DJs). They come from Burkina Faso, Malawi, Mexico, Brazil, France, Ethiopia, India, Senegal, Morocco, Colombia, and beyond. Some devote themselves to sustaining folkloric traditions, while others update or hybridize them.

In the former category, you’ll find ecstatically funky Addis Ababa troupe Ethiocolor, austere but passionate local Arab group Karim Nagi & Huzam Ensemble, and many of the virtuosos at Ragamala; the latter includes California-based Afro-Latine dance-party starters Quitapenas, intricately propulsive Burkina Faso groove machine Baba Commandant & the Mandingo Band, and the hypnotizing French Occitan voice-and-percussion kaleidoscope of San Salvador.

Of the 35 acts previewed here, 17 perform at two big all-ages events: Ragamala at the Chicago Cultural Center on September 29 and the Global Peace Picnic in Humboldt Park on September 30. More than 45 percent of those 35 acts are locals, a bit more than last year and a steep increase from 2019, when they accounted for around 15 percent of the bill.

The increasing percentage of locals—acts that don’t require DCASE to find money for travel or lodging—suggests discouraging things about the level of city funding for this festival (or the difficulty of supplementing it with grants and sponsorships). But the locals themselves remain worth seeing: they include the cosmic globe-trotting fusions of Magic Carpet, the bittersweet tropical-tinged pop rock of Rudy De Anda, and the playful bossa nova of Silvia Manrique.

The festival continues to make extensive use of conventional music venues, a practice it began in part to help those businesses rebound from pandemic shutdowns. Such venues make for concerts on an intimate scale, but only the Old Town School admits all ages. This approach unfortunately also replicates a bias built into Chicago’s infrastructure.

Nine of the fest’s 11 venues are on the north side—all but the Promontory in Hyde Park and the Cultural Center downtown. The 2022 and 2019 installments were somewhat better about this: they included shows at the Logan Center for the Arts, Reggies Rock Club, the Beverly Arts Center, and Ping Tom Memorial Park.

On the plus side, the total number of World Music Festival Chicago artists has stayed pretty consistent since 2019. DCASE has accomplished this partly by focusing on emerging acts rather than paying for Pritzker Pavilion headliners. I’m sorry to see that this year’s fest hasn’t booked anyone from east Asia—I loved the Yandong Grand Singers and Gamelan Çudamani in 2019—but longer flights cost more.

It’s increasingly difficult to simply exist anywhere in an American city without being expected to spend money—look what’s happening to public libraries, especially under Republican rule. So we shouldn’t take for granted that the World Music Festival offers us ten days of dazzlingly varied performances for free. We’ve all paid for this programming already, and we ought to enjoy it.

In 2006, the World Music Festival booked more than 60 artists at more than two dozen venues, but it’s shrunk since founder Michael Orlove and his staff were laid off in 2011. We won’t convince the city to return the festival to its glory days unless we demonstrate demand by coming out to these shows en masse. So please mask up if you’re headed to an indoor gig—we’re in the middle of another COVID-19 surge—and open your ears. Our species developed music tens of thousands of years before written language, and you’ll be surprised how much you can hear. Philip Montoro

World Music Festival Chicago 2023 is presented by the Chicago Department of Cultural Affairs and Special Events (DCASE) and sponsored by the Chicago Transit Authority and Millennium Garages. Additional support is provided by the following partners: Center Stage, the Chicago Park District, the International Latino Cultural Center of Chicago, People of Rhythm Productions, South Asian Classical Music Society-Chicago, and the South Asia Institute.

Click on an artist or event to jump to details on that show.

Click the up arrow at the end of an item to return here.

Friday, September 22

Baba Commandant & the Mandingo Band, Magic Carpet

Saturday, September 23

Cheikh Ibra Fam, Gizzae

Sunday, September 24

Ethiocolor; Clinard Dance’s Flamenco Quartet Project meets Chicago blues, jazz, and rap

Monday, September 25

Bab L’ Bluz, Así Así

Tuesday, September 26

San Salvador, Silvia Manrique

Wednesday, September 27

Al-Qasar, Karim Nagi & Huzam Ensemble

Thursday, September 28

La Perla, Kafolike School of Percussion

Friday, September 29

Ragamala: A Celebration of Indian Classical Music

Saturday, September 30

Global Peace Picnic

Quitapenas, Rudy De Anda

Sunday, October 1

Madalitso Band, Luciano Antonio’s Funk no Samba

Friday, September 22

Baba Commandant & the Mandingo Band, Magic Carpet, DJ Onwa

Fri 9/22, 10 PM (doors at 9 PM), Martyrs’, 3855 N. Lincoln, 21+

Baba Commandant & the Mandingo Band come from the landlocked West African nation of Burkina Faso, which tends to enter Americans’ consciousness only when international media report on its economic or political travails. But Burkina Faso has a vibrant culture that encompasses traditionally oriented and forward-thinking movements in cinema, fashion, theater, music, and more, and this concert gives us a welcome glimpse of it. “Baba Commandant” is the stage name of Mamadou Sanou, who’s been active in various ensembles since the 1980s, singing and playing donso ngoni. This six-string harplike instrument, which uses a large gourd resonator like a kora, was until recently played almost exclusively in ceremonial settings by a society of traditional hunters known as “donso” or “dozo”; it can also be heard in the music of Toumani Koné, Yoro Sidibe, and Don Cherry. (The smaller, banjo-like ngoni familiarized in the U.S. by Bassekou Kouyaté is sometimes called “jeli ngoni” or griot’s ngoni.) Baba and his associates in the Mandingo Band have crafted a driving, groove-forward sound that leavens classic Afrobeat in the muscular mode of Fela Kuti with an easy, dance-friendly lope and a sparkling lattice of strings and tuned percussion. On the combo’s three albums, all released by Seattle label Sublime Frequencies, chiming melodies leap between layers of liquid guitar, brittle balafon, and lilting donso ngoni.

Baba Commandant & the Mandingo Band released Sononbela in 2022.

Baba Commandant & the Mandingo Band balance elements drawn from the past half century of West African music, many with roots that go back much further than Afrobeat. In some ways they’re a bit old-school, but they also address immediate concerns in their songs (“Chasser les Sachets,” for instance, urges listeners to give up disposable shopping bags on environmental grounds). Baba never lets Auto-Tune near his rough, gravelly voice, and he clearly doesn’t need to—his adroit, unerring singing, in French and several Burkinabè languages, always lands in just the right spot. The band’s grooves are likewise free of electronic intervention, and for exactly the same reason. For this tour they’re stripped down to a quartet, trimming away the balafon and a layer of percussion from the arrangements on last year’s Sonbonbela. Their road lineup consists of Baba Commandant, drummer Abbas Kaboré, bassist Wendeyida Jessie Josias Ouedraogo, and guitarist Issouf Diabaté, whose splendid playing flows with spectacular ease between intricate phrases, terse rhythms, and distorted leads. Bill Meyer ↑

Formed more than 20 years ago, Chicago groove wizards Magic Carpet weave together hypnotic rhythms and cosmic melodies that conjure visions of not-yet-imagined places and endless possibilities. Their music merges influences from Africa, India, the Caribbean, and the Middle East with jazz, funk, reggae, psychedelic rock, and more. Their easy fluidity and impressive chops have made them a beloved local institution, able to fit seamlessly into any setting, whether an intimate club or a massive street festival—though many north-siders know them from a long-running weekly gig at Ras Dashen Ethiopian Restaurant in Edgewater. Magic Carpet recorded their spectacular new LP, Broken Compass (out last month on local label FPE Records), in 2016 with a lineup of drummer Makaya McCraven, percussionist Ryan Mayer, guitarist Temuel Bey, saxophonist Fred Jackson Jr., keyboardist Tewodros Aklilu, and bassist Parrish Hicks. Sadly, Hicks passed away in 2017, but his bandmates have carried on with new music and new members. Since the recording of Broken Compass, they’ve added vocalist and dancer Tracy King to their lineup, and they’ve also recruited a handful of regular substitutes—McCraven is frequently busy with his own gigs, of course, and Aklilu lives in Ethiopia and tours with Teddy Afro. For their World Music Festival performance, Magic Carpet will consist of Mayer, Bey, Jackson, and King, joined by bassist Joshua Ramos, guitarist and oud player Alex Wing, and drummer Justin Boyd. Break out your best dancing shoes—it’ll be worth it. Jamie Ludwig ↑

Magic Carpet finished recording their new album, Broken Compass, in 2016.

Saturday, September 23

Cheikh Ibra Fam, Gizzae, DJ TopDonn

Sat 9/23, 10 PM (doors and DJ at 9 PM), Avondale Music Hall, 3336 N. Milwaukee, 21+

In 2022, Senegalese singer Cheikh Ibra Fam released his first album under his own name, Peace in Africa (Soulbeats), but his career stretches back some 15 years. He’s worked as a vocalist with Orchestra Baobab, a venerable Afro-Cuban dance band whose five-decade history has made it an institution in Senegal, and he’s recorded three hip-hop albums (virtually unfindable in the States) under the name Freestyle.

Cheikh Ibra Fam released Peace in Africa in March of last year.

Given his pedigree, you’d expect Cheikh Ibra Fam to be a polished performer—and you would not be disappointed. In press materials, he describes discovering the soul music of Otis Redding when he was ten as a life-changing event, but as Western touchstones go, Al Green seems more obvious—Cheikh’s silken, soulful vocals are a perfect fit for the lush Afro-pop beats on Peace in Africa. Some of his album performances, including the title song, are buttressed by big electronic production that’s obviously angling for a dance-floor hit. But he’s best when he keeps things relatively analog, like he does with the itchy, butt-wiggling riffs and rhythms of “The Future,” a duet with the commanding Balla Sidibé, one of the founding singers of Orchestra Baobab (who died three days after the sessions in 2020). Another highlight, with a backing track that sounds plausibly like a band, is the reggae-tinged “Diom Gnakou Fi,” which features the remarkable vocals of French Cape Verdean artist Mo’Kalamity.

When Cheikh plays live, he sometimes pares his material down even further—in summer 2021 he posted a lovely medley to YouTube that includes an arrangement of “Cosaan” for just guitar, bass, sax, and voice. He glides and sways over gentle rhythms that feel almost as Latin as West African (and as much smooth jazz as either). Cheikh Ibra Fam doesn’t overwhelm or dazzle, but he’ll sneak up on you and win you over with his warm, feel-good vibe. Noah Berlatsky ↑

Long-running Chicago band Gizzae, anchored by bassist and front man Brian “Rocket” Rock, exemplify reggae’s global reach and the midwest’s work ethic. The group formed in 1992 from members of two groups that both had more than a decade of gigging under their belts: Moja Nya from New York City and Dallol from Chicago, whose members reconvened here in 1979 after leaving Ethiopia and in the 1980s joined Ziggy Marley’s Melody Makers. Gizzae became Sunday-night regulars at Lincoln Park reggae hub the Wild Hare, and though Rock is the only remaining member from those early years, the group have maintained their soulful roots-reggae sound (flecked with country, rock, and gospel) even as their lineup has undergone extensive turnover. When Gizzae came together, for instance, drummer and keyboardist Evans Atta-Fynn (who’s since left the band) was still living in his native Ghana and playing in popular highlife act the Western Diamonds. He moved to Chicago with that group in 1997, bringing him closer to his future bandmates. On Gizzae’s most recent release, the 2008 self-released album Roots Like a Lion, they maintain a Talmudic scholar’s strict adherence to the basic building blocks of reggae—they infuse every accented upbeat and harmonized vocal with learned devotion, even as they flavor their music with twangy harmonica or psychedelic guitar. There’s no reason reggae can’t be big enough to contain 80s rock frizz (“I Just Can’t Wait”), doo-wop harmonies (“Going Steady”), and smooth-jazz piano froufrou (“Love Me”). In Gizzae’s hands, all sorts of pop sounds can work in harmony with buoyant, soothing reggae. Leor Galil ↑

The most recent Gizzae album, 2008’s Roots Like a Lion

Sunday, September 24

Ethiocolor; Clinard Dance’s Flamenco Quartet Project meets Chicago blues, jazz, and rap

Ethiocolor is on tour as part of Center Stage, CenterStageUS.org. Sun 9/24, 3 PM (doors at 2 PM), Sleeping Village, 3734 W. Belmont, 21+

Melaku Belay had a rough time of it growing up on the streets of Addis Ababa in the 1980s, but that’s also where he developed the lifelong love for classic Ethiopian dance and music that’s since taken him far beyond his country’s borders. Today, Belay is a global artistic ambassador who delivers major speeches abroad on the need to preserve this heritage; he also works directly to preserve it by running the multipurpose Fendika Cultural Center, which he founded in 2016 as an expansion of long-running Addis Ababa venue Fendika Azmari Bet. He leads a troupe called Fendika, which has visited Chicago as recently as 2018, as well as the associated folkloric music and dance ensemble Ethiocolor, which performs regularly at the Fendika center and likewise carries its mission around the world.

Ethiocolor’s self-titled 2014 debut album

Ethiocolor features instruments with centuries-long histories, including washint (wooden flute), masenqo (one-string bowed fiddle), and krar (pentatonic lyre). Though the group uses drums arranged like a stripped-down version of a Western trap set, its rolling, swinging beats derive from the Ethiopian pentatonic funk that emerged in the late 1960s (pioneers of the style can be heard on the Ethiopiques compilation series). The music usually provides improvised commentary on current personalities or situations, much like griot songs in the western part of Africa. The accompanying dances, called eskista, feature rapid pistoning of the shoulders, which also directs the musicians’ energy. Throughout a performance, the artists build up a communal ecstasy that makes it clear why this tradition has endured. Onstage, Belay immerses himself completely in the action: during introspective passages, he can enter a trancelike state, and when the music swells in energy, he erupts in moves that have earned him the nickname “the Walking Earthquake.” Belay also embraces any modern technology that can spread his message of cultural and musical heritage: he draws on his collection of vintage Ethiopian jazz LPs when he spins tunes online as DJ Melaku. Frustratingly, the authorities in Ethiopia are hardly unified in support of Belay’s mission—Fendika currently faces a demolition order, the result of a government-sponsored private development. A GoFundMe page has been set up to help Belay and his community fight back. Aaron Cohen ↑

Ethiocolor is part of Center Stage, a public diplomacy initiative of the U.S. Department of State’s Bureau of Educational and Cultural Affairs with funding provided by the U.S. government, administered by the New England Foundation for the Arts in cooperation with the U.S. Regional Arts Organizations. General management is provided by Lisa Booth Management, Inc.

Wendy Clinard’s dance company has been devoted to flamenco since she founded it in Pilsen in 1999, but the group’s interpretations are far from orthodox. Clinard Dance uses the intimate interplay that drives flamenco—among dancer, guitarist, and singer—as the engine for even its most daring experiments. Critic and painter Dmitry Samarov described Clinard’s process in a 2018 Reader article: “Although her work is rooted in flamenco,” he wrote, “she’s just as likely to find new moves watching a bus driver steer his or her vehicle down Halsted as in a performance hall or theater.” The occasion for Samarov’s story was itself a daring experiment: Clinard developed a multimedia collaboration called Everyday People/Everyday Action with Japanese photographer Akito Tsuda, inspired by his 1990s photos of people in Pilsen. Nine years ago, Clinard Dance launched the Flamenco Quartet Project, whose lineup consists of Clinard, guitarist Andrea Salcedo, percussionist Diego Alvarez, and vocalist José Díaz “El Cachito.” Since 2021, they’ve made a point of collaborating with Chicago artists outside their turf, with the goal of using flamenco as a lens to see blues, jazz, and hip-hop in new ways. In keeping with that mission, the other people involved in this World Music Festival set are activist and rapper King Moosa, jazz and R&B vocalist Joan Collaso, and blues harmonica player and singer Billy Branch. Leor Galil ↑

Monday, September 25

Bab L’ Bluz, Así Así

Mon 9/25, 9 PM (doors at 8 PM), Empty Bottle, 1035 N. Western, 21+

The beginnings of Moroccan-French psychedelic rock band Bab L’ Bluz date to 2017, when Moroccan singer and guitarist Yousra Mansour met French guitarist and producer Brice Bottin. They decided together to learn how to play the guimbri (aka gimbri, guembri, or sintir), a three-string bass lute associated with the Gnawa people of Morocco. Traditional all-night Gnawa rituals associate different spiritual entities with different rhythms plucked on the guimbri, using ecstatic music and dance to evoke and communicate with these spirits. These ceremonies foreground a central pillar of Gnawa music: capturing trancelike states through hypnotic repetition. The Gnawa are descendants of enslaved people from the Sahel, south of the Sahara in present-day Nigeria, who were brought north to Morocco and later converted to Islam; their music, in its drumming and singing and purpose, reflects this multicultural reality.

Bab L’ Bluz released their debut album, Nayda!, in June 2020.

Bab L’ Bluz build on Gnawa sounds and usher them into the present. On “Gnawa Beat,” the opener to their electrifying 2020 debut, Nayda! (Real World), they build a tight, swerving groove from bubbly electric guimbri (plus its smaller, higher-pitched cousin the awisha), a heavy sashaying beat, and rustling percussion. Flute melodies periodically adorn the sinuous melodies, but Mansour’s commanding vocals lead the charge. The band’s joyful long-form jamming primes listeners to luxuriate in the textural pleasures of their music: “El Gamra” contains a striking passage of wordless, hocketing vocals, “El Watane” seems to firmly anchor every sound with its shuffling beat, and “Waydelel” builds a solo on rebab (a hoarse-sounding traditional fiddle) from frantic repeated phrases powered by a sudden shift to a staggered beat. Album closer “Bab L’ Bluz” begins in media res, so it feels like you’re stumbling upon a public festival. The instruments’ infectious syncopation and dotted rhythms seem to conjure a centripetal force that drags you into the mesmerizing arrangement, where the guitar solo can overwhelm you with the force of its roaring timbre. Bab L’ Bluz’s songs are always like this: they draw you in and leave you pleasantly dazed. Joshua Minsoo Kim ↑

Guitarist and vocalist Fernando de Buen López formed an eclectic indie-rock outfit called El Mañana in Mexico City in 2009, but when he moved to Chicago in 2012, his bandmates didn’t follow—the group released an album of old material in 2014, but by then they were defunct. In 2018, though, de Buen López ended his music-making drought by resurrecting the project under the name Así Así with new collaborators: the current lineup consists of drummer Ben Geissel, keyboardist and vocalist Celeen Rusk, bassist Sam Coplin, and guitarist Christian Caceras. Despite his relocation, de Buen López continues to write all his lyrics in Spanish, which he says works best with the music he makes. On the 2022 full-length Mal de Otros, Así Así create structured, compact fusions of indie rock, dance, surf, cumbia, and other Latin styles, in contrast to El Mañana, who played looser, jammier songs—in an interview with WBEZ’s Sasha-Ann Simons, de Buen López attributed the change to the pandemic, which prevented Así Así from developing material in live rehearsals. But that relatively understated approach has served his new band well: the title track of Mal de Otros collides space-age surf rock and clanging postpunk in a frenetic, psychedelic odyssey, while “Descubrimientos” builds slowly from a pensive melody into a sleek, industrial throb that could shake a dance floor. Jamie Ludwig ↑

Fernando de Buen López’s first full-length under the Así Así name

Tuesday, September 26

San Salvador, Silvia Manrique

Tue 9/26, 7 PM (doors at 6 PM), Constellation, 3111 N. Western, 18+

I love Occitan folk music, but I feel like the term needs unpacking for the layperson. “Occitan” doesn’t describe a particular country or even a single culture—it’s a dwindling minority language spoken mostly in parts of southern France, northwest Italy, and northeast Spain (specifically Catalonia, where it’s an official language). The Occitan language is beautiful, and so is Occitan folk music, which survives mostly in the valleys of the Piedmont region in Italy. Common instruments include button accordion, clarinet, violin, harmonica, and hurdy-gurdy (called “vioulo” in Occitan), and yearning, soul-searing Occitan ballads accompany all sorts of celebrations in the Piedmont valleys. Because the ruggedness of the region’s terrain has enforced a degree of isolation on its people, each valley has been able to persist in its own melodies and dance steps, even when their communities hold songs in common.

San Salvador write their own music to accompany mostly traditional lyrics.

Young French group San Salvador carry on this ancient tradition, though they name-drop John Coltrane and My Bloody Valentine in their press materials—and when you hear their music, you’ll instantly recognize the trance-inducing qualities it shares with modal jazz and shoegaze. San Salvador are nearly an a cappella outfit—their six voices ebb and flow in dense, hair-raising harmonies, moving in intricate counterpoint that’s augmented only by handclaps, a few low-pitched drums, and tambourine. If this seems like it’d add up to thin arrangements, you’re underestimating what six voices can do—the band’s latest release, the 2021 album La Grande Folie, has a remarkably dense and vivid sound. “Quau te Mena” begins by stacking interlaced vocal ostinatos over hushed drones before exploding into soaring, overlapping melodies, while “La Grande Folie” opens with an immediate rhythmic attack, fueled by snapping beats and deftly woven chants. San Salvador’s music manages to be incredibly intense but also soothing, so that it feels pagan and divine at once. Onstage they’re sure to bewitch anyone within earshot. Steve Krakow ↑

Chicago jazz singer Silvia Manrique recalls wearing out the grooves of the bossa nova tracks on her dad’s favorite albums when she was six years old. That’s part of why she decided in 2006 to focus exclusively on Brazilian music—and why in 2008 she founded the group Beaba do Samba, which specializes in samba, its subgenre pagode, and bossa nova. Manrique’s fourth appearance at the World Music Festival arrives as she emerges from an almost complete performance hiatus that began around a decade ago. In 2020 she was diagnosed with breast cancer, and she says her battle with the disease has changed the way she approaches singing—she takes more risks now.

In May of this year, Manrique dropped her first solo release, the four-song EP Sonho. Recorded in Brazil with coproducer and Afro-Brazilian singer Fabiana Cozza (Manrique’s vocal coach), the EP combines Latin and Brazilian material in a bass-forward mix. It includes a bolero that nods to Manrique’s Mexican American heritage and funky spins of bossa nova classics that share the folksy playfulness of Brazilian singer-songwriter Joyce Moreno.

The EP also showcases Manrique’s vocal prowess, of course. Under Cozza’s encouraging tutelage, she says, she’s been “tapping into the entire system of what makes sound”—a technique her coach calls “o corpo de voz,” meaning “the body of the voice.” It’s easy to hear the work Manrique has put in, because it’s given her already heart-fluttering leaps into bossa nova standards a new boldness. Sheba White ↑

Wednesday, September 27

Al-Qasar, Karim Nagi & Huzam Ensemble

Wed 9/27, 7 PM, Maurer Hall, Old Town School of Folk Music, 4544 N. Lincoln, all ages

What happens when you bring together musicians from Algeria, Morocco, Egypt, France, and the United States? Al-Qasar provide one answer with their sublime blend of face-melting psychedelic rock and North African trance music. They like to call it “Arabian fuzz,” and it pays homage to the Middle Eastern psych-rock bands of the 60s and 70s. Al-Qasar represent an update of that cosmopolitan pan-Arab sound for contemporary ears.

Their debut album, last year’s Who Are We?, weaves together its kaleidoscopic grooves by combining electric guitar with Arabic lutes (electric saz and awtar) and kit drums with traditional percussion (including frame and hand drums, the tabla-like tbila, and the metal castanets often called karkabou in Algeria). “Awal” perhaps best embodies this marriage of Middle Eastern and Western stringed instruments, with guest guitarist Lee Ranaldo (formerly of Sonic Youth) haunting the track with slow-burning, dissonant licks.

Al-Qasar’s debut album includes guest appearances by Lee Ranaldo and Jello Biafra.

Al-Qasar’s poetic Arabic lyrics often touch on political topics, such as the pervasiveness of injustice and government corruption. The seven-minute epic “Ya Malak” speaks on the power imbalance between the world’s haves and have-nots, and it features a not-so-subtle cameo by Jello Biafra (founding front man of Dead Kennedys) reciting an English translation of Egyptian revolutionary poet Ahmed Fouad Negm. Other guests include Algerian oud master Mehdi Haddab, who adds a knotty, impassioned solo to the end of “Barbès Barbès,” and Brooklyn-based Sudanese expat Alsarah, who pours her heart out on “Hobek Thawrat.” She sings about the turbulent aftermath of the 2019 military coup in her homeland, and the chorus even borrows the words of a slogan chanted at protests. Alejandro Hernandez ↑

Chicago percussionist and composer Karim Nagi hails from Egypt, and his expertise in Arab folk traditions colors his music to its roots. Nagi records and performs with the Huzam Ensemble, a quartet of Chicagoans from across the Arab diaspora. On the 2021 album Huzam, he plays a small frame drum called a riqq—essentially a tambourine with a fish-skin membrane. The rest of the group consists of Ronnie Malley (Palestine), who plays the oud, a short-necked fretless lute; Naeif Rafeh (Syria), who plays the ney, an end-blown wooden flute; and Emad Roushdy Ibrahim (Egypt), who plays a violin in an Arabic tuning. “Huzam” is the name of a common maqam (an Arabic melodic mode or scale), and every song on the album employs it. This particular maqam begins and ends on a microtone, placing it firmly outside the framework of conventional Western harmony; Nagi also uses rarely performed traditional Arab art-music forms, in a further effort to create something he calls “un-imperial, unoccupied, and distinctly ours.” Throughout Huzam, the ensemble perform with passion and precision, transforming Nagi’s compositions into immersive environments. Much of the music is heterophonic, with multiple instruments performing simultaneous versions of the same melody, but the players also take occasional solos: when Rafeh steps out near the end of “Longa Huzam,” his peripatetic playing evokes the blissful, aching final steps of a long walk through summer heat. Nagi and Huzam Ensemble will perform original compositions as well as traditional material. Leor Galil ↑

The Bandcamp notes to Huzam describe the titular maqam as “mystifying” and “ecstatic.”

Thursday, September 28

La Perla, Kafolike School of Percussion

Thu 9/28, 7 PM (doors at 6 PM), the Promontory, 5311 S. Lake Park Ave. W., 21+

Founded in Bogotá, Colombia, in 2014 by Karen Forero, Giovanna Mogollón, and Diana Sanmiguel, La Perla is a percussion and vocal trio whose music interlaces vocal harmonies with indigenous flutes called gaitas and a wide variety of percussion: African drums, scrapers, bells, shakers, and more.

La Perla root their compositions in the traditional music of Colombia’s Caribbean coast, but they aren’t bound by it. “We do traditional music our way,” Mogollón told Spanish online newspaper El Español in 2018. As a band of bogotanas, these women stand out among practitioners of this musical style—it originated in rural communities, and it’s often considered the domain of men. La Perla fortify their music with punk attitude and touches of rock and hip-hop, sometimes adding beatboxing to their explorations of South American and Caribbean rhythms such as Dominican merengue, Cuban rumba, and Peruvian chicha. Their lyrics often center women’s rights and social justice, and their 2019 single “Bruja” (featured in Colombian Netflix series Siempre Bruja) became a popular anthem at protests and solidarity marches. Its title means “Witch,” and it indicts misogyny toward women who dare to be different: “Me querían quemar / Ya no tengo miedo / Me quité el disfraz / Yo hago lo que quiero, no me van a callar” (“They wanted to burn me / I am no longer afraid / I took off the costume / I do what I want”).

La Perla’s 2019 single “Bruja”

La Perla titled their 2022 album Callejera, a term for street wanderer or explorer that also has less positive connotations (it can mean “streetwalker”). The record’s 12 tracks include songs that address the rights of the working class and our responsibility to protect the planet from the travesties of climate change, and their danceable modern take on ancestral Afro-Colombian rhythms has the kind of energy that can fuel collective struggle. This performance promises to demonstrate the power of community and celebration. Catalina Maria Johnson ↑

The 2022 La Perla album Callejera

In 2013, Chicago percussionist and educator Sekou Tepaka Lunda Conde founded the nonprofit Kafolike School of Percussion to educate students about West African music, cultural history, ethics, and folklore. Conde began his own studies in 1978 at Muntu Dance Theatre, founded in Chicago in 1972, and he currently serves as the theater’s executive director. He’s spent decades sharpening his skills on the djembe, a large-bodied goblet-shaped hand drum that can produce a wide, expressive range of tones, from piercing pings to deep, resonant booms. Developed around 800 years ago by the Mandinka people (who now live mostly in Mali and Guinea), it’s often played in a traditional percussion ensemble, and it’s loud enough to stand out as a solo instrument in that context.

Conde’s biography includes an impressive list of master musicians—among them Mamady Keita and Famoudou Konaté from Guinea and Moussa Traore from Mali—who’ve guided him on the djembe and taught him the musical culture of the Mandinka. For this World Music Festival performance, Conde and friends will demonstrate a sampling of what Chicagoans can learn through intensive study at the Kafolike School. Leor Galil ↑

Friday, September 29

Ragamala: A Celebration of Indian Classical Music

Presented in collaboration with the South Asia Institute, South Asian Classical Music Society-Chicago, and People of Rhythm Productions. This event continues into the morning of Saturday, September 30. Fri 9/29, 6 PM-8 AM, Preston Bradley Hall, Chicago Cultural Center, 78 E. Washington, third floor, all ages

The Sanskrit word “Ragamala” translates to “garland of ragas.” Since ragas are the fundamental melodic materials of Indian classical music, you might expect a Ragamala to be a music festival—especially because that’s what the city calls this one. But “Ragamala” actually describes a historical style of painting: a set of ornate miniatures depicting ragas with colorful, narrative imagery. Indian classical music has historically developed multidisciplinary, synesthetic forms, and Chicago’s Ragamala participates in that tradition by presenting a “garland” of artists, some budding and others in full flower, who’ve built bridges between their Indian classical training and disciplines such as film, theater, dance, and rock ’n’ roll.

Like its European counterpart, Indian classical music evolved out of devotional practices, blossomed with the patronage of royal courts, and is now beloved around the world. Over the course of thousands of years, interactions among peoples of diverse religions, languages, and geographies generated its rich musical landscape, which is sorted today into two large, regionally demarcated genres, Hindustani (north) and Carnatic (south). Especially in the north, a profusion of musical terms, song forms, instruments, and melodic styles have come from Arabic and Persian sources. Indian classical compositions in general have been shaped by Islamic, Sufi, Buddhist, Jain, and Hindu spiritual ideas, as well as by secular poetry; they’re also sung in many languages, including Sanskrit, Tamil, Telugu, Urdu, Punjabi, Hindi, Kannada, and Rajasthani.

In recent years, violent propagandists have sought to erase this vibrant history of cultural plurality, instead pressing Indian classical music into service to uphold Hindutva, a Hindu nationalist ideology—a destructive lie. This ancient cultural treasure belongs to everyone, and Ragamala embodies that truth.

The vast sea of Indian classical music contains an unfathomable number of fascinating sounds to explore, and at Ragamala you’ll have the opportunity (14 hours of opportunities, in fact) to dive in, wade, float, or do whatever you please. You can drop in for a few hours after dinner, on a typical evening concert schedule; you can roll through at 2 AM, after the clubs close; you can arrive at sunrise, do stretches, and meditate; or you can go whole hog and experience the epic magnificence of the entire marathon event. No matter how much time you commit, Ragamala will commit itself to your memory for days and weeks to come. Leslie Allison ↑

6-7:15 PM Unfretted featuring Sruti Sarathy, Vishaal Sapuram, and Akshay Anantapadmanabhan

The trio Unfretted derive their name from a quality shared by Sruti Sarathy’s violin and Vishaal Sapuram’s chitravina. Neither instrument has frets, and this makes them ideally suited to the melodic contours and expressive bends at the heart of the Carnatic ragas they play. These musical gestures might remind you of the slide-guitar licks that impart an emotional punch to country blues. You might also sense similarities between lap-steel technique and the method used to play the chitravina: the instrument is laid flat in front of the musician, who stops the strings with a handheld cylinder made of glass, metal, or wood. There’s no confusing the chitravina’s complex, nasal tone for that of any other stringed instrument, though—if anything, it sounds a bit like a human voice. This is a highly desirable quality in Carnatic music, where even instrumental performances of a raga relate to the lyrics of a song. Carnatic music, developed in southern India, is usually performed by a trio of one rhythmic and two melodic instruments, and the latter two often divvy up the roles of lead and accompaniment. That delineation isn’t necessarily strict, though, and in the case of Unfretted, either Sapuram or Sarathy might play lead. Akshay Anantapadmanabhan articulates complex percussive melodies and rhythmic figures with mridangam (a double-headed drum) or his own voice. This is a return engagement for Sarathy, who played two Ragamala sets in 2022, but it’s the first Unfretted date in Chicago. Bill Meyer ↑

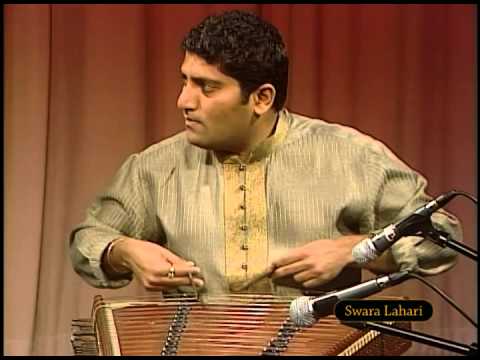

7:45-9 PM Gaurav Mazumdar and Amit Kavthekar

In 1969, the stoned throngs at Woodstock were rocked by the north Indian classical duo of Ravi Shankar (sitar) and Alla Rakha (tabla). These legendary partners did more than anyone else to catalyze the flow of Indian music into the mainstream of Europe and the United States. More than 50 years later, the crowd at Ragamala will be rocked by two of their musical descendants—Gaurav Mazumdar (sitar) and Amit Kavthekar (tabla).

Mazumdar is among Shankar’s disciples, and he’s taken up the unofficial mantle of Sitar Ambassador to the World. As such, he’s performed at an Olympic opening ceremony and at the Vatican for the pope. In July he released an album called Crossing Cultures: India and the West (Ropeadope), which consists of four original compositions for sitar, violin, cello, and tabla. Mazumdar seems to maintain a dialogue with his instrument, as though it commands him as much as he commands it, and this makes clear how intrinsic the act of listening is to his technique. The layered resonances of his sitar’s sympathetic strings rise up with the might of a chanting choir to hold the melodies aloft, then melt into a plush carpet that draws them close with a soft gravitational pull. Whatever a raga’s mood, Mazumdar’s attentive, grounded playing ensures you hear every detail.

Gaurav Mazumdar’s new Crossing Cultures accompanies his sitar with violin, cello, and tabla.

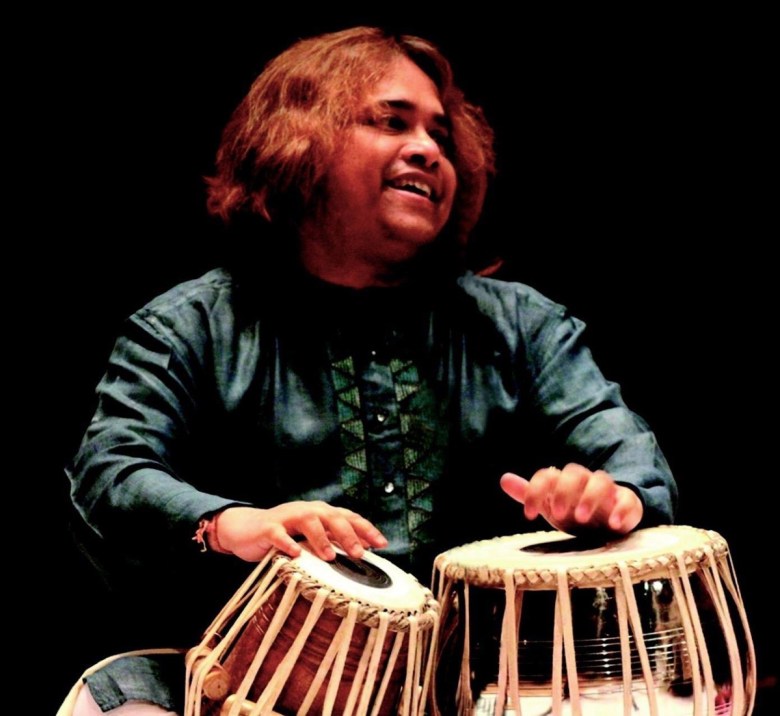

Amit Kavthekar, who’s graced the Ragamala stage many times, was trained from early childhood by Alla Rakha and later by Rakha’s tabla-playing son Zakir Hussain, who might be more famous than his father today. Kavthekar has emerged from this tutelage with the ability to play his paired drums with the impact of an entire ensemble. He’s a charismatic and open performer, and he shares with Mazumdar not only a lineage but also a dedication to exploring the synergies among arts traditions. Together, this powerhouse duo is carrying forward the expansion of Indian music beyond India that their teachers famously began in the 1960s. Leslie Allison ↑

9:30-10:45 PM Ramakrishnan Murthy, Charumathi Raghuraman, and NC Bharadwaj

This stunning set is the only one at Ragamala to showcase the foundational relationship between violin and voice in Indian music. In training and performance, these instruments act as extensions of each other, embracing in an entwined timbre that’s more than the sum of its parts. Two distinguished young Carnatic musicians—violinist Charumathi Raghuraman and vocalist Ramakrishnan Murthy—will unite with fiery mridangam player NC Bharadwaj to deliver the power of this melodic pairing.

Over the past decade, Chennai-based Murthy has galvanized the international Carnatic community, winning prizes, attracting press, and booking performances on several continents. He’s a magnetic performer known for his creative, multidisciplinary aesthetic—in 2019 he collaborated with a visual artist and architect in a performance that combined ragas with paintings. Murthy embellishes his distinctively pearly upper-range voice with round, dancing gamakas (elaborations) that burble like a stream rushing over stones. With his open sound and expressive face, he uncovers each phrase as if for the first time.

Raghuraman is a commanding violinist with a correspondingly impressive performance history. Her ambitious, nuanced playing relishes the secrets hidden between notes; her silken melodies flow with the same organic potential for surprise as a train of thought. Onstage she has a cool, grounded composure that complements Murthy’s intrepid flights of fancy, a balance they’ve developed over years performing together. Illuminated by the focused, burnished patterns of Bharadwaj’s mridangam, Raghuraman and Murthy will maneuver through a thoughtfully curated Carnatic repertoire, delivering their own polished, vibrant, and original interpretations. Leslie Allison ↑

11:15 PM-12:30 AM Max ZT, Kunal Gunjal, and Amit Kavthekar

Santoor player Kunal Gunjal carries on the legacy of his groundbreaking teacher, the late Shiv Kumar Sharma, who’s credited with integrating this south Asian hammered dulcimer into north Indian classical music in the 20th century. Previously performed mainly in Kashmiri music, the santoor is unlike other Hindustani stringed instruments. Instead of creating the distinctive glides between notes (called meends) characteristic of north Indian strings, the player strikes the santoor’s 100 strings with thin mallets, producing sparkling waves of tones that peal and crash into one another. Each pitch is discrete, like those of a harp, but Gunjal has developed a technique that manipulates rhythm and volume to create halos of polyphony from the resonance hanging in the air between notes. With light, rapid trills, he manifests a kind of effervescent tickle for the ears.

In a duet for the ages, Gunjal will be joined by fellow santoor master and Sharma disciple Max ZT, aka Max Zbiral-Teller. Based in Brooklyn, Zbiral-Teller has traveled from Senegal to Mumbai to pursue his training, and he’s a major innovator of the dulcimer in contemporary American music. Zbiral-Teller’s expansive explorations can be heard on his improvised 2022 solo release, Daybreak, created as a musical salve to the pain of the pandemic, and in the ensemble House of Waters (see the Global Peace Picnic on Sat 9/30). Both Gunjal and Zbiral-Teller zealously uphold the santoor’s relatively new place in Indian tradition, and they’ve dedicated themselves to further expanding the instrument’s reach. Gunjal cowrote a 2018 album of cinematic scores featuring the santoor, Nature of All Things, while Zbiral-Teller appears on the 2020 album Periphery by singer-composer Priya Darshini.

Gunjal and Zbiral-Teller will perform with tabla player Amit Kavthekar (see tonight’s 7:45 PM set). The sounds of 200 strings and two drumheads will immerse listeners in a radiant dreamscape of melody and rhythm from which they won’t want to awaken. Leslie Allison ↑

1-2:15 AM Akkarai S. Subhalakshmi, Akkarai S. Sornalatha, R. Sankaranarayanan, and Vijay Ganesh

The violin is generally thought of as a Western classical instrument, but it’s been a staple of Carnatic music for more than 200 years and Hindustani music for nearly a century. It’s an ideal tool for the glides and drones characteristic of Indian classical performance. Baluswamy Dikshitar is credited for pioneering the use of the instrument in Carnatic music in the late 1700s, and he and his peers adjusted its tuning and playing style to fit a new context. In the West, of course, the violin is usually held between the chin and shoulder and played while sitting in a chair or standing, but Indian musicians typically perform while sitting cross-legged on the floor, with the bottom of the violin leaning against the neck or chest and the scroll balanced on the foot. To Western eyes, they may appear to be playing it upside down.

The Akkarai sisters, aka Akkarai S. Subhalakshmi and Akkarai S. Sornalatha, are two of southern India’s most celebrated classical violinists and vocalists. Following in the footsteps of their violinist father, Akkarai S. Swamynathan, and grandfather Suchindram S.P. Sivasubramaniam, the sisters began playing at an early age. Their grandmother R. Sornambal performed harikatha (a form of traditional musical storytelling), and Subhalakshmi participated in a concert when she was four years old.

The sisters’ traditional sound is instantly recognizable to anyone familiar with classical Indian music. But as they saw away together, you may also hear hints of the painful pleasure of raspy Appalachian fiddle tunes. Live, the Akkarai sisters are a joy to watch, whether they’re playing in unison or tossing the lead back and forth—each vigorously bows when it’s her turn and grooves along to the beat when it isn’t. They’re joined for this set by two mridangam players, R. Sankaranarayanan and Vijay Ganesh. With its 2,000-year history, this double-headed drum predates the violin by a few centuries, but in combination they sound like they were made for each other. Noah Berlatsky ↑

2:45-4 AM Jai Sovani, Giri Aigalikar, and Praneet Marathe

Ragas don’t just evoke a mood, they embody a mood—they directly install it in the listener’s consciousness. Central to Indian classical music, these melodic frameworks act more like atmospheres or environments, and to master them is more than a craft. It’s a way of life.

Few understand this better than Jai Sovani. The Chicagoland Hindustani vocalist practices three to four hours per day when her schedule allows, with the goal of keeping herself immersed in the various ragas. She compares her studying to breathing.

“The deeper you go into it, the more it envelops you,” she says. “You do it subconsciously. You’re not thinking about inhaling or exhaling. You’re into the music the whole time, without even actively doing it.”

With her lustrous, agile voice, Sovani completely inhabits the ragas. She glides between notes with grace and tirelessly sustains long tones as if traversing a vast space. Sovani is looking forward to this predawn set, in part because certain ragas are associated with certain times of day—most of her concerts take place in the afternoon or evening, so this will be a rare chance for her to publicly perform early-morning ragas that convey freshness, devotion, and tranquility.

Sovani will be joined by Giri Aigalikar on tabla and Praneet Marathe on harmonium. All three were raised in the Indian city of Pune. Sovani says this shared background adds to their onstage chemistry. “They grew up in similar atmospheres, so they know how to bring out the performance,” she says. “It’s like one homogenous piece of art that we put together. It just works.” Austin Woods ↑

4:30-6 AM Saraswathi Ranganathan and Sai Raghavan

Veena master Saraswathi Ranganathan has been a leader in Chicago’s international music scene for decades, and her many appearances at Ragamala have made her a beloved fixture. The veena is a large wooden lute with its own surround-sound speakers—it has a bulbous resonator at each end, one positioned on each side of the player’s body. The veena is often called India’s most ancient instrument, but its diverse palette of sounds exists outside time and can call to mind unexpected hints of searing blues guitar or warbling theremin.

Ranganathan is a hometown champ—she’s won a Chicago Music Award, composed for the Chicago Humanities Festival, played for Goodman Theatre, and joined the historic Chicago Immigrant Orchestra. She pursues an ethos of intercultural community building, both as a musician and as the founder of two organizations she continues to run: Surabhi Ensemble, a performance collective whose thoughtful, genre-spanning compositions celebrate music as a common global language, and the Ensemble of Ragas School, a nonprofit that uses musical training to help students see humanity as an interconnected family.

Even without these sustained contributions to Chicago culture, Ranganathan’s exquisite playing would speak for itself. Holding court with the elaborately painted veena across her lap, she plucks the instrument’s main strings to craft careening, exuberant melodies that slide, bob, and weave; meanwhile she brushes the drone strings to summon haunting, nuanced harmonies. At this year’s Ragamala, she will duet with Chennai-based Sai Raghavan on mridangam. Raghavan shows his enjoyment of the music through his body language; his movements radiate the feelings of the songs, and his eyes invite you to wonder along with him at the drum’s mysteries. Ranganathan and Raghavan have collaborated before, and they’re sure to build on their chemistry—expect wild creativity, dizzying virtuosity, and generous, welcoming energy. Leslie Allison ↑

6:30-8 AM Lyon Leifer and Hindole Majumdar

Chicago-based bansuri player Lyon Leifer and Milwaukee-based percussionist Hindole Majumdar are like-minded musicians who both excel as educators. In their duo, where Majumdar plays tabla, they blend their expertise in Hindustani music. Leifer has played the bansuri, a keyless bamboo flute, for more than 50 years, and he crafts many of his own instruments. Using his well-honed breath control, he quietly navigates the intricacies of serene ragas, and his fleet fingers help him push through rapid tempos and ornamental improvisations. His dexterity on the bansuri owes a debt to his early years studying with Devendra Murdeshwar, one of India’s most prominent advocates for the instrument. Along with mastering the ragas’ myriad styles, Leifer founded the South Asian Classical Music Society-Chicago, one of the presenters of Ragamala. He wrote an instruction book based on Murdeshwar’s teachings, How to Play the Bansuri, and he also gives lessons online. Along with immersing himself in Indian classical music, he’s also worked extensively within European-derived idioms; among his many accomplishments, he played first flute with the Lake Forest Symphony.

Majumdar has played tabla since childhood and continues to transmit the discipline as the founder of the Hindole Majumdar School of Music and Dance in Milwaukee. His globally minded musical vision includes collaborations with Uzbek percussionist Abbos Kosimov and Mexican American drummer Glen Velez. Also an entrepreneur, he’s released albums on his own Sunanda label. Leifer and Majumdar’s past performances, which include previous installments of Ragamala, suggest that they may be ideal onstage partners; Majumdar’s easy grasp of different polyrhythms matches Leifer’s melodic flow in a seemingly relaxed but undoubtedly intense intuitive dialogue. Aaron Cohen ↑

Saturday, September 30

Global Peace Picnic

This mini festival features nine sets on two stages. The artists on the ¡Súbelo! Stage are presented in partnership with the Chicago Latino Dance Festival of the International Latino Cultural Center of Chicago. Sat 9/30, 1-7:15 PM, Humboldt Park Boathouse, 1301 N. Sacramento, all ages

¡Súbelo! Stage, 1-1:25 PM Mexican Folkloric Dance Company of Chicago with Mariachi Perla de México

The renowned Mexican Folkloric Dance Company of Chicago, founded in 1982, shares the vast richness of the iconic dances from Mexico’s 32 states. The company’s costumes are works of art in and of themselves, reflecting different regional traditions as well as the stories narrated by the dancers’ movements. Their twirls and spins propel their ornate, flowing skirts into ephemeral sculptures of cloth and color, shaped and reshaped by their precise, intricate footwork.

The dance company will be accompanied for this performance by Mariachi Perla de México, founded in 1997 by Margarito “Ricardo” Rivera, originally from Amatitán, Jalisco. The state of Jalisco is the birthplace of modern mariachi (and tequila, which makes total sense). The current lineup of Mariachi Perla includes the genre’s classic instruments: trumpet, violin, guitar, guitarrón (a large bass guitar), and vihuela (a higher-pitched five-string guitar). Their repertoire covers the full range of emotions expressed so well by mariachi music, from tragic lovelorn despondency to euphoric celebration.

This program will showcase two cultural traditions, both transplanted here generations ago, that have grown deep, vital roots in our community. It’s sure to be a feast for the senses, as well as a display of Mexico’s millennial history and Chicago’s immigrant pride. Catalina Maria Johnson ↑

¡Súbelo! Stage, 1:30-1:55 PM Samba1 Brazilian Dance Group with Chicago Samba

One of Chicago’s finest Brazilian music ensembles and one of its most exuberant Brazilian dance companies join forces for this high-energy performance. Chicago Samba, directed by vocalist and multi-instrumentalist Mo Marchini, have been a local staple for more than three decades, stirring up crowds with lively takes on popular Brazilian styles—including not just samba but also bossa nova, forró, chorinho, and blistering all-percussion batucada jams. At this show, they’ll be joined by the long-running Samba1 Brazilian Dance Group, led by Edilson Lima. They’ll kick up the heat with snappy, hip-shaking steps that evoke the “anything goes” spirit of a great Carnaval celebration. The bubbling rhythms will have you dancing your tail off, and even if you’d rather just watch, the brilliantly colorful plumed costumes (designed by Chicagoan Daniel Sabec) will provide a feast for the eyes. Jamie Ludwig ↑

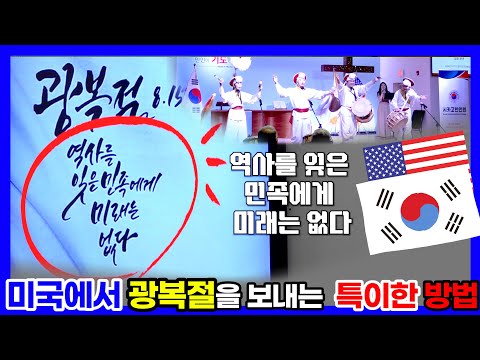

Global Stage, 2-3 PM Korean Performing Arts Institute of Chicago (KPAC)

The northwest suburban Korean Performing Arts Institute of Chicago (KPAC) was founded ten years ago to celebrate a traditional Korean performing art called pungmul. Pungmul includes drumming, dancing, and singing, and it was originally performed as part of collective farmwork and to accompany rituals or mask dances at community gatherings. Korean villagers would use pungmul performances at harvest festivals to speak to the hardships they experienced, but the practice declined in the early 20th century as a consequence of urbanization and suppression by Japanese colonial authorities. In the 1960s, pungmul enjoyed a resurgence at Korean pro-democracy protests, as the people returned to addressing their grievances together through public song and dance.

KPAC presents several other artforms as well, including the semi-improvised solo folk music called sanjo and the dramatic musical storytelling called pansori, but their outdoor public performances for city festivals tend to employ dazzling folk-drumming ensembles made up of KPAC instructors and students. I’m hoping this set will include a demonstration of sangmo pankut, in which the performers wear a special hat (the sangmo) with a long ribbon on top that they can spin using motions of their heads while simultaneously dancing and drumming. Salem Collo-Julin ↑

¡Súbelo! Stage, 3-3:25 PM Center of Peruvian Arts with SolAndino

A troupe of dancers from Chicago’s Center of Peruvian Arts will perform with local Peruvian band SolAndino in a program that honors Indigenous cultures and centers decolonization. Founded by Rubén Pachas and Jessica Loyaga, the Center of Peruvian Arts is based in Belmont Cragin and presents workshops and performances across Chicagoland, highlighting traditional Amazonian, Andean, and coastal Peruvian dances. SolAndino are a four-piece consisting of Pedro Verástegui, Pedro Verástegui Jr., Alberto Otarola, and Huguito Gutiérrez, and they’ll back the dancers with traditional guitar, Andean flute, charango (basically a tiny guitar with strings in pairs, sometimes made from an armadillo’s shell), and percussion (including the box drum or cajón, which originated in Peru). The dancers’ vivid traditional clothing combines with the musicians’ stirring songs to give audiences a taste of Peru’s distinct regions while creating an intentional celebration of humanity and the natural world. Taryn Allen ↑

¡Súbelo! Stage, 3:30-3:55 PM Bomberxs D’Cora

Led by Humboldt Park native Ivelisse Diaz, Bomberxs D’Cora are a Chicago-based collective of dancers, singers, and drummers connected to an Afro-Puerto Rican performing arts school, La Escuelita Bombera de Corazón, that Diaz founded in 2009. Both organizations are dedicated to bomba, an art form developed more than 400 years ago by enslaved African people in Puerto Rico. They combined dance, percussion, and voice in running dialogues as a means of communication, self-expression, and resistance. Bomba dancers sing call-and-response melodies to the beats of hand drummers, one of whom (the “primo” drummer) follows the lead dancer’s movements; other traditional percussion includes the cuá (a wooden barrel on its side, played with two sticks) and maracas.

Telemundo Chicago broadcast this segment on La Escuelita Bombera de Corazón in 2022.

The sounds, movements, and lyrics of bomba merge African diasporic traditions with European and Indigenous influences. The long, flamenco-style skirts and petticoats often worn by the dancers originated in Spain; the maracas and cuá come from the Caribbean’s native Taino culture; and the drums (barriles de bomba) are historically made from goatskin and rum barrels, reflecting bomba’s roots among enslaved African sugar-plantation workers who found ways to assert their identity in the face of colonial rule. Bomberxs D’Cora will bring this history to vivid life in a way that’s sure to stick in your heart and mind. Jamie Ludwig ↑

Global Stage, 4-5 PM House of Waters

Hammered dulcimer player Max ZT (see also Ragamala on Fri 9/29) started learning his instrument as a seven-year-old in Chicago, taking weekly lessons from folk singer-songwriter Kat Eggleston. After moving to upstate New York to attend Bard College, where he studied folk, jazz, and Celtic music, among other things, he expanded his musical horizons abroad: over the course of several years, he took repeated trips to Senegal to learn from the Cissoko griot family (especially kora player Fodé Cissoko) and traveled to India on a grant to study Indian classical music with santoor master Shiv Kumar Sharma. In the late 2000s, he met Japanese six-string bassist and jazz improviser Moto Fukushima in New York, and in short order they’d started a band. Their idiosyncratic trio House of Waters (currently with a revolving-door drum spot, occupied by Antonio Sanchez for the brand-new album On Becoming) perform original instrumentals that capture something from all the genres and countries that have informed their aesthetic. ZT’s intricate technique, inspired by the way kora players weave together lead and bass lines, provides a range of melody that might recall gospel bluegrass on one song and Kashmiri folk on another. House of Waters play sneakily complicated music: it sounds superficially like it belongs in the background (and the group have in fact scored several films), but their dazzling musicianship reliably breaks through the glossy surfaces of their sound to command your attention. Salem Collo-Julin ↑

¡Súbelo! Stage, 5-5:25 PM Tamboula Ethnic Dance Company

Founded by dancer and choreographer Daniel Desir, who’s still the troupe’s artistic director, Tamboula Ethnic Dance Company has been sharing Haiti’s dance culture with Chicago for more than two decades. Tamboula combines elements of contemporary jazz and ballet with traditional Haitian dance forms (including Ibo, Kongo, Dahomey, Nago, Yanvalou, and Mayi) that merge African foundations with Taino, French, and Spanish influences. Tamboula makes tradition approachable, achieving the troupe’s goal of transcending stereotypes and demystifying Haitian culture. The dancers look at once grounded and light as air, and the drumming will stir your body with its pulse. Taryn Allen ↑

¡Súbelo! Stage, 5:30-5:55 PM Laruni Hati Garifuna Dance Group

Formed in 2010, the local Laruni Hati Garifuna Dance Group consists of drummers, singers, and dancers who specialize in traditional dances of the Garifuna people (called Garínagu in the Garifuna language). The Garifuna are of mixed African and Indigenous Caribbean ancestry, descendants of island natives and formerly enslaved Africans shipwrecked on Saint Vincent in the 1600s. Garifuna Settlement Day, a national holiday in Belize, commemorates the arrival of the Garifuna on that country’s shores on November 19, 1802, after being deported from the nearby Grenadine Islands by the British. Members of the Laruni Hati Garifuna Dance Group plan and perform at a Chicago celebration of that holiday each year. The group’s repertoire includes hunguhungu, chumba (a solo dance similar to salsa), and punta, the most iconic expression of Garifuna culture—its lively drumming, dancing, and singing unite the communities of the Garifuna diaspora and connect its past to its present. Tyra Nicole Triche ↑

Global Stage, 6-7:15 PM Amayo

Abraham “Duke” Amayo spent more than 20 years fronting Brooklyn-based Afrobeat band Antibalas, but since he kicked off his solo career in 2021, he’s been embracing seemingly disparate inspirations in much the way a good festival of world music does—he’s not worrying whether things seem to fit together, but rather making sure people are enjoying themselves. Amayo joined Antibalas in 1999, a few months into the group’s first year, after baritone saxophonist Martin Perna and guitarist Gabriel Roth met him in Williamsburg. Before his time in Antibalas, Amayo ran a storefront space called the Afro-Spot, which served as a home for his fashion line, his screen-printing business, and his dojo (he’s a sifu in the Jow Ga style of kung fu, a discipline he’s been practicing since the late 70s). Amayo’s first gig with Antibalas was filling in for a percussionist who couldn’t make it, but with his onstage charisma and skill at writing lyrics, he soon evolved into the group’s lead singer. In 2020 Antibalas released their final album with Amayo, Fu Chronicles, and it’s as close to a solo project as he could’ve gotten: he wrote all the songs and created the cover art, and his Nigerian heritage and martial-arts background informed the material. The album combines the moody side of Antibalas’s take on 1970s Fela-style Afrobeat with serene and focused lyrics that sound lifted from The Art of War. On his own this year, Amayo has been performing with a smaller band, though “smaller than Antibalas” (which could be as big as 15 pieces) still leaves room for shekere, congas, and horns. You can expect some lion dancing along with your booty shaking. Salem Collo-Julin ↑

Quitapenas, Rudy De Anda, DJ La Colocha

Sat 9/30, 10 PM (doors at 9 PM), Chop Shop + 1st Ward Events, 2033 W. North, 21+

“We play dance music that is fun. . . . It’s happy music,” says Quitapenas vocalist and guitarist Daniel Gómez. The southern California band’s name translates to “remove worries,” which also speaks to what they’re trying to do with their infectious tropical Afro-Latine fusions: leave listeners without a care in the world.

A group of Inland Empire–based first-generation friends (some of whom went to high school and college together) formed Quitapenas in 2011, uniting around their shared passion for tropical and traditional dance music from far-off places such as Peru, Colombia, Angola, Cape Verde, and Haiti. Though they had prior experience playing rock, they wanted to dig into Afro-Latine dance-music styles that had developed in the 60s, 70s, and 80s—not just to celebrate their sounds but also to help keep them alive.

“Obviously, we are not from these countries, so [the music] gets reinterpreted through our lens of southern California and also the perspective of students using the Internet as crates, as vinyl crates—digital crates where we get to pull music and pull the things that we like from each area, each culture, each sound,” Gómez says.

The most recent Quitapenas single, released in January 2022

Quitapenas have increasingly leaned into experimenting with tropical rhythms, including Congolese soukous, Colombian champeta, Haitian kompa, and Cape Verdean funaná. “We have improved our craft writing songs,” Gómez says. “We communicate better together, and we have a clearer vision of what we want, what we want to sound like and want to represent.” Cumbia, salsa, merengue, and electronics—mostly drum pads and samples—round out the Quitapenas sound. They offer an excellent introduction to the diverse diaspora of music composed by the next generation of multicultural art makers. Sandra Treviño ↑

Singer-songwriter Rudy De Anda moved from Los Angeles to Chicago in 2020. In a May 2023 interview with Vogue México, he said he’d taken a liking to our city while on tour. At first the pandemic made gathering a challenge, but he found a community of like-minded Chicagoans that included plenty of Latine folks and Spanish speakers. Among the people De Anda befriended was Blake Rhein, a guitarist and producer who’s played in R&B combo Durand Jones & the Indications. De Anda had an album mostly written when he arrived, and Rhein helped him finish the songs on what became Closet Botanist (Colemine/Karma Chief), which came out this April. The record’s poppy, understated 60s-style rock carries De Anda’s wistful, lovelorn voice like it’s ferrying him in a palanquin. He sings in English and Spanish, and no matter the topic, he delivers his lyrics with doe-eyed warmth. On “WYD,” sunny keyboard swells, relaxed guitar riffing, and a busy but wispy drumbeat nudge the song from its restrained verses into its tender, swooning chorus—De Anda starts out skipping through clipped, nimble phrases, then opens up and lets himself soar. Simultaneously melancholy and suave, his performance will keep you following whatever moves he makes. Leor Galil ↑

Rudy De Anda wrote Closet Botanist in Los Angeles and Chicago and recorded it in Austin, Texas.

Sunday, October 1

Madalitso Band, Luciano Antonio’s Funk no Samba

Sun 10/1, 8 PM (doors at 7:30 PM), Hideout, 1354 W. Wabansia, 21+

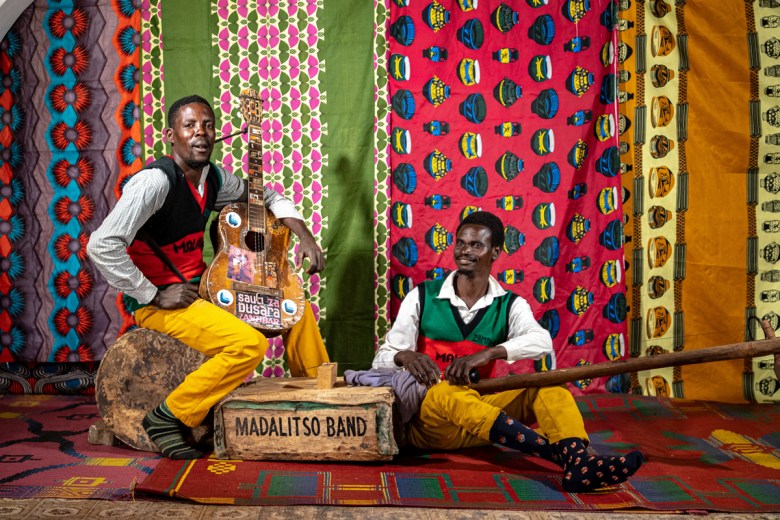

In 2009 a local producer saw Yobu Maligwa and Yosefe Kalekeni busking outside a shopping center in Lilongwe, Malawi. Now the duo is known as the formidable Madalitso Band, and they tour the world with an updated take on their country’s folk music. Kalekeni plays a four-string guitar and a cowskin foot drum, while Maligwa plucks a homemade babatoni, basically a variety of washtub bass whose single string is played with a slide. The guitar fills a role analogous to the hand-built banjos in 1970s Malawian music (similar to the traditional ngoni), and you can hear the spirit of Alan Namoko’s old blues recordings in Madalitso Band’s rhythms. The eight songs on their third album, last year’s Musakayike (Les Disques Bongo Joe), live up to the title—it translates to “don’t doubt us.” On opener “Ali Ndi Vuto,” the duo’s lively vocal back-and-forth mirrors the jubilant pulse of the drum and guitar, and the simplicity of the composition allows it to radiate playfulness. Halfway through the track, Maligwa digs into the babatoni with a rapid series of notes whose resonant thwack crescendos into an almost distorted buzz—it’s a thing of modest beauty. The cyclical vocal melodies of “Mwaza” suffuse it with a joyous splendor that’s complemented and heightened by the urgent thrum of the babatoni. Throughout these songs, the duo maintain an elegant dance: the vocals most often work in perfect lockstep with the instrumentation, but they also maneuver expertly in and out of transcendent moments where they soar beautifully above it. That’s especially true for album closer “Jingo Janga,” which alternates between passages where vocal harmonies help drive the beat and showcases of Maligwa and Kalekeni’s vocal prowess. Madalitso Band often sing of love—on the title track, for instance, they insist that marriage should be rooted in love, not money—but you don’t have to understand the lyrics to feel how warmhearted this music is. Joshua Minsoo Kim ↑

Madalitso Band’s second international release, Musakayike, consists entirely of original material.

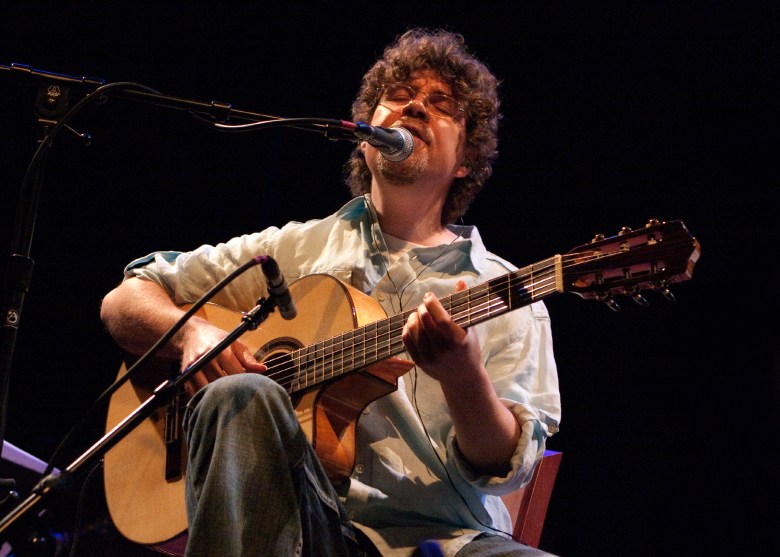

Luciano Antonio arrived in Chicago via a circuitous route from a rural area of the Brazilian state of Paraná, where he was one of several musicians in his family. The guitarist, singer, and composer has been kicking around in local music circles for decades, and he first came here while working toward a bachelor’s degree in music performance at the University of Missouri–Kansas City. He was invited to join Chicago Samba (see the Global Peace Picnic on Sat 9/30), and until he finished his education and relocated permanently, he commuted back and forth from Kansas City each week.

More recently, Antonio has been performing solo acoustic sets at local venues and fronting small combos (usually with piano, bass, and drums) that showcase his knowledge of Brazilian classics and skill with group improvisation. Funk no Samba, he says, is a new group put together specifically for the World Music Festival, inspired by a recent conversation he had about 70s Brazilian funk and samba funk.

Funk no Samba may be new, but Antonio’s bandmates are all previous collaborators of his: Heitor Garcia will play hand percussion, building loops in real time with electronic assistance, while bassist Marcel Bonfim and drummer Jonathan Marks will (in Antonio’s words) “funk it up in a coherent manner with the grooves that Heitor will lay down.” Because Antonio also composes, his sets are a robust mix of classics and originals. He promises detours into material by the likes of Tim Maia, Seu Jorge, and Jorge Ben Jor during his band’s own fusion of experimental funk and samba. Sheba White ↑