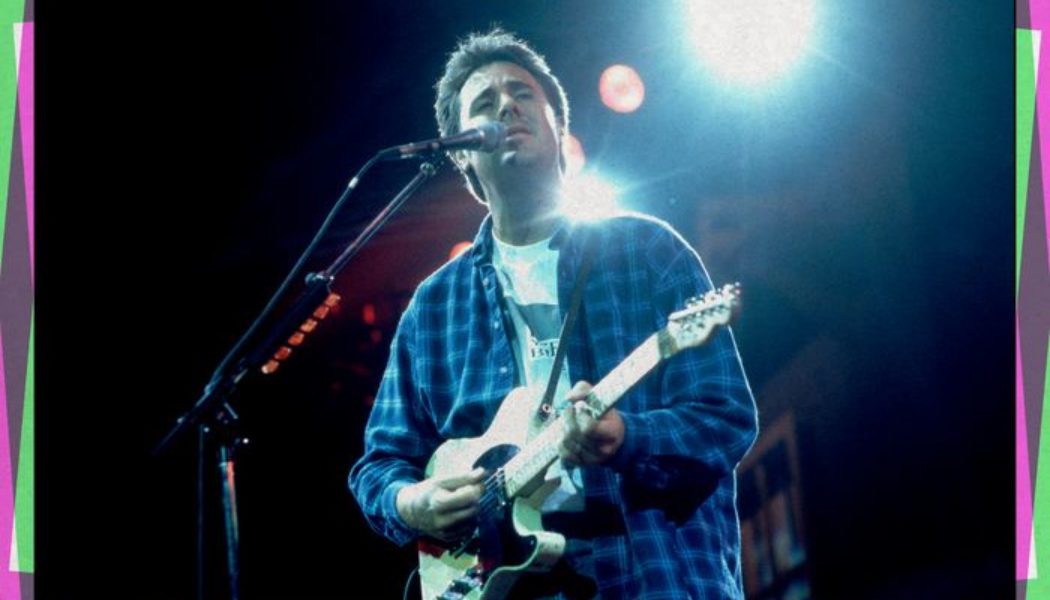

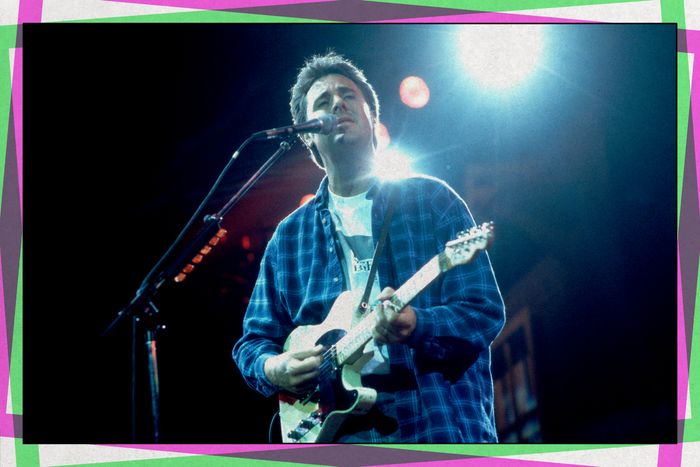

“I’m a much better songwriter today than I was 30 years ago when I had all those hits. Photo-Illustration: Vulture. Photo: Paul Natkin/Getty Images

Vince Gill was so certain from a young age he would be a career musician that, when he explains as much, it doesn’t even sound arrogant. “I always felt like my ears never lied to me,” he says. “They’d tell me, ‘You can sing good enough and play good enough and write good enough to be in this world’ — even though other people were telling me I couldn’t.”

Gill’s prolific career began in earnest when he became the lead singer for the already-successful Pure Prairie League and immersed himself in the L.A. country-rock scene, singing backup and playing guitar for artists like Rosanne Cash, Emmylou Harris, and Rodney Crowell before his own country hit-making began in earnest. Twenty albums and 22 Grammys later, the 66-year-old has worked with more than 1,000 artists as a singer or instrumentalist (or both), expanding beyond country and into rock, R&B, and other genres. Currently, he’s got a gig as the Eagles’ occasional stand-in for the late Glenn Frey, and he just released a tribute album to Ray Price called Sweet Memories with the legendary steel guitarist Paul Franklin.

“I had fun in the process at every stretch,” says Gill while reflecting on his long career. “I was not despondent when I was struggling, I was fine. Because I sang and played on everybody’s records, and was doing things that made it feel like I was contributing and a part of it — like I was good enough. The stretch of selling out arenas and selling a bunch of records, it was just like, ‘Okay, well, this is part of the deal too.’”

Patty Loveless was probably the most special because of what happened when our voices blended together. I sang on her first hit record and she sang on my first hit record. One of the reasons “When I Call Your Name” did so well was because of Patty singing that high harmony. When we were in the studio recording — I had tracked it, all the solos were done — nobody thought, “This is the one.” Nobody said anything about it until Patty’s voice got on it. That last element really gave it a whole lot of its definition. People may not realize why they love it, but a lot of times it’s those little nuggets that happen on a record. Patty’s voice was that, and it was pretty sweet.

I could pick a hit, but one of my favorite songs that I’ve written — a song I really felt was well-crafted — is called “Young Man’s Town.” “You feel like an old memory hangin’ round, and man you’ve gotta face it, it’s a young man’s town.” I now work for one of the greatest songwriters that ever lived in Don Henley, and totally unsolicited, he told me that was his favorite song of mine. A lot of times, I think we equate the best things with the most successful things, and I don’t know that I subscribe to that. There are certain songs that mean an awful lot to me that are just buried on a record somewhere.

For the longest time, I was too bashful to sing. I could always hide behind my guitar, keep my head down, and duck any attention that was coming my way. Then I wound up being in bands where I was the guy who could sing better than everybody else. I became a singer not so much intentionally but by default. I was fine being just a guy in the band, whether I was the lead singer, the harmony singer, the sideman — whatever role I had, I just enjoyed the process. Little by little, I found myself wanting to become an artist. I started wanting to write my own songs. The cool thing about being a writer as well as a musician is that I can tailor-make melodies in my writing that suit my voice. I guess I was meant to sing and play, but I honestly feel I sing like a musician. When I’m playing, I say, “Okay, how would I sing what I’m about to play?”

You know, I haven’t lost anything. I’m 66 and I can still sing as high as I always did. Actually, the lowest notes are usually harder for me. The key that I write any given song in will be predicated on how hard it is for me to get to the lowest part of the melody and make that work.

So those key changes in “When I Call Your Name” are easy?

They kind of are, though they’re getting a little more challenging as the years go by. For the most part, my songs are still in the same keys; I think now I do “When I Call Your Name” a half step lower — mostly because it’s how I want to play the guitar. If I’m doing a bunch of songs in a row, I won’t want to have to use a capo and retune. “Whenever You Come Around,” I do a half step higher than I did on the record.

I’ll be out there touring, and everybody gets run down and loses their voice a little bit. When I do, then I can’t sing high — I sing a good bit lower then, and I finally sound like a man for a change. But the band is so good, it doesn’t matter what you throw at them. They can play the songs in any key that you choose to do.

The first bluegrass song I ever learned was that Stanley Brothers song, “Think Of What You’ve Done” — I’d heard “Foggy Mountain Breakdown” and Bill Monroe, but that was the first one I actually set out to learn how to sing and play. It’s stuck with me forever. The Stanley brothers had that blood-brother harmony that was so cool, and reminded me of the Everly Brothers and the Louvin brothers, family-type things that I was so drawn to. Every now and then there’s a combination of voices that’s just really, really powerful. But when they’re related, when the bloodlines align, there’s something in there that makes it so special. I feel that when I sing with my daughters — I finally get to hear it in our voices blending together.

Guy Clark used to say, “If one word doesn’t add to the story, then it doesn’t belong.” What’s interesting about writing now is that I’m so much more willing to wait for the right word, for the right phrase, for the right cadence, than I used to be. It all has to work, it all has to matter, and it all has to have a point. I’m just more willing to edit now than I ever have. Just because you can cram all those words in a line, do you really think you should? I don’t want to cut that out. Well, maybe you need to.

It’s similar to the way that I choose to play. If I play 12 notes, I think, “Could I say more with eight notes? Can I say more with six notes?” You’ve just always got to be willing — and I think that comes with a little more experience — to edit yourself. It’s a good thing. What I love most about music is emotions. Being impressed is a much different emotion than being moved. The music I hold dearest is the music that moves me, that makes me feel something more than, “Oh, wow, look what they just did.” You can fool ‘em with all kinds of stuff, but at the end of the day, you don’t want anybody to go “Whoooo!”, you want everybody to applaud for a long time. That’s a deeper feeling than the screaming that just lasts for two seconds.

Oooooh, maybe there’s one. Certain songs require you to play a certain way. “Liza Jane” needs that busier kind of solo. “One More Last Chance” needs that kind of solo. But a solo on “Whenever You Come Around,” it’s more melod-driven and not a whole bunch of information. I got a really good lesson when I was a young musician playing on a record. I played a solo on something, and the producer came on the talkback and goes, “Man, that was impressive. Can I ask you to try it one more time? This time, just play me half of what you know.” Neither is wrong. And neither is right. It’s all a matter of what somebody is drawn to — some people love to hear shredders, they just love all that stuff. I never did. My way’s not right, it’s just my way.

Just the fast songs, “Oklahoma Borderline,” “Liza Jane” — those songs that are zippin’ pretty good in a two-feel. I got invited by Eric Clapton to go play his first Crossroads Guitar Festival in 2004. Amy went with me, and somehow I was sandwiched between James Taylor and Joe Walsh. Not fun for the token hillbilly. I think I opened with “Oklahoma Borderline,” and it’s quite a showpiece for the guitar, you know? Amy watched from the crowd, and she came back and said, “They introduced you, and everybody kind of shrugged — like, he’s not Jeff Beck, he’s not some guitar hero god. You started playing ‘Oklahoma Borderline,’ and everybody started leaving en masse to go get a beer. Then you got to the solo, and I watched all these people turn around and find their way back in again.”

Last year, I did about 35 shows over a couple of months. Because of COVID, I hadn’t played much. My style of playing is fairly intense, and I’d been doing my job with the Eagles, which is not a big guitar gig for me — it’s more of a singer gig. I had the hardest time keeping up. It was really fun to make myself woodshed and practice. It took the whole summer to finally feel like I was back to normal. My brain was fine, but my brain wouldn’t coexist with my hands. It’s intense. I’m sitting there going, “OK, is it the fact that I’m in my 60s?” And it came back, and it was a good feeling to have it show up. I won’t be let out of that aging trap, but I’ll get as many licks in while I can. It’s always come pretty easy, and so that was rough on me.

On my previous record, Okie, there are some neat songs about different subjects that are a little more touchy. My goal in writing songs is not to point fingers, but just to be a fair observer of what I see. One is called “What Choice Will You Make,” and it’s about a young girl that gets pregnant. It never says what she should or shouldn’t do, it’s strictly about the moment that she’s in. It doesn’t have a solution, there’s no judgment. I think that the songs are a whole lot better without being preachy. My songs are not that: I’ve got a new song called “March On, March On” and it’s all about race relations in our country. Country music tends to be afraid of some of those things — they want to go down the path of least resistance. But you can have conversations about all these hard subjects if you’re gracious about it. I’m proud of it — it’s not afraid to deal with a tough subject.

My best songs are coming now. They’re not ever going to be noticed as much, but I’m a much better songwriter today than I was 30 years ago when I had all those hits. I kind of got a train rolling — radio would stick with you for a pretty good while, if you finally got the door open. I go back through all those old songs, and I’m grateful for them, but I think there’s an awful lot of good songs still left in me.

I remember singing with Gladys Knight. We were the first ones to sign on to do a duet for this record called Rhythm, Country and Blues. It took R&B artists and put them with country artists. I felt her apprehension — I could see it in her face. She didn’t have a clue who I was. We went in to rehearse the tune in the studio, and she sang and was the great Gladys Knight; then I started singing and she just lit up. She started smiling and I go, “Okay, we’re good. I just passed the test.” We hit it off, and had the best time — and because of that collaboration, I wound up being the first white guy on the cover of Jet magazine. Pretty cool street cred minute for me. I learned as much from Black music as I did any kind of music. Creative people, people that do what I do, we don’t care where it comes from. It’s what Duke Ellington said: there are two kinds of music, good and bad.

How to stay out of the way. Honestly, it sounds funny to say, but the worst thing that happens is when you’re a control freak. The real beauty of making music is the democracy of it. If nobody cares who gets the credit, it’s amazing what you can accomplish — I wish our country would do that. They should really call a producer a reducer, that’s what your job is, just figuring out what you really need to serve that song and tell that story. It’s like making a movie. If you cast the right people in the right roles, they won’t disappoint you because they come to the table already knowing what not to do.

The ‘90s were such a powerful stretch, because everything aligned. There were a couple of channels devoted just to country music — which had never happened — tons of record companies, tons of artists, tons of people selling millions of records. It was by far the most visible and successful stretch in the history of country music in terms of numbers, and you couldn’t have picked a better stretch to have fallen into, you know? I still love my mentors and my teachers, and I’ll always be drawn to the ‘50s and ‘60s era of the music more so than the ‘90s, when I was successful and so many of my contemporaries were successful, I still think that era prior that I grew up on was better. But that’s just a matter of what I like. I think we revere our past and think, “Oh, that was the greatest stuff ever.” But I contend that in every stretch of creativity, there were a lot of great records and a lot of bad records. With time, we’ve forgotten so many of the bad records and the bad songs. We only remember the great ones. Now we’re inundated with what we’re inundated with today, but the really great things will be the things that everybody remembers 20, 30, 40 years from now.

Gill’s 1990 hit that peaked at No. 2 on the Country Singles chart.

Gill’s first big gig was as the lead singer for the already-established country rock group Pure Prairie League; now, he often sings lead in his role with the Eagles, as Glenn Frey’s replacement.

1989’s “Timber, I’m Falling in Love,” which Loveless’ first No. 1 on the Hot Country Singles chart.

Bestselling singer-songwriter Amy Grant, Gill’s wife of 23 years.