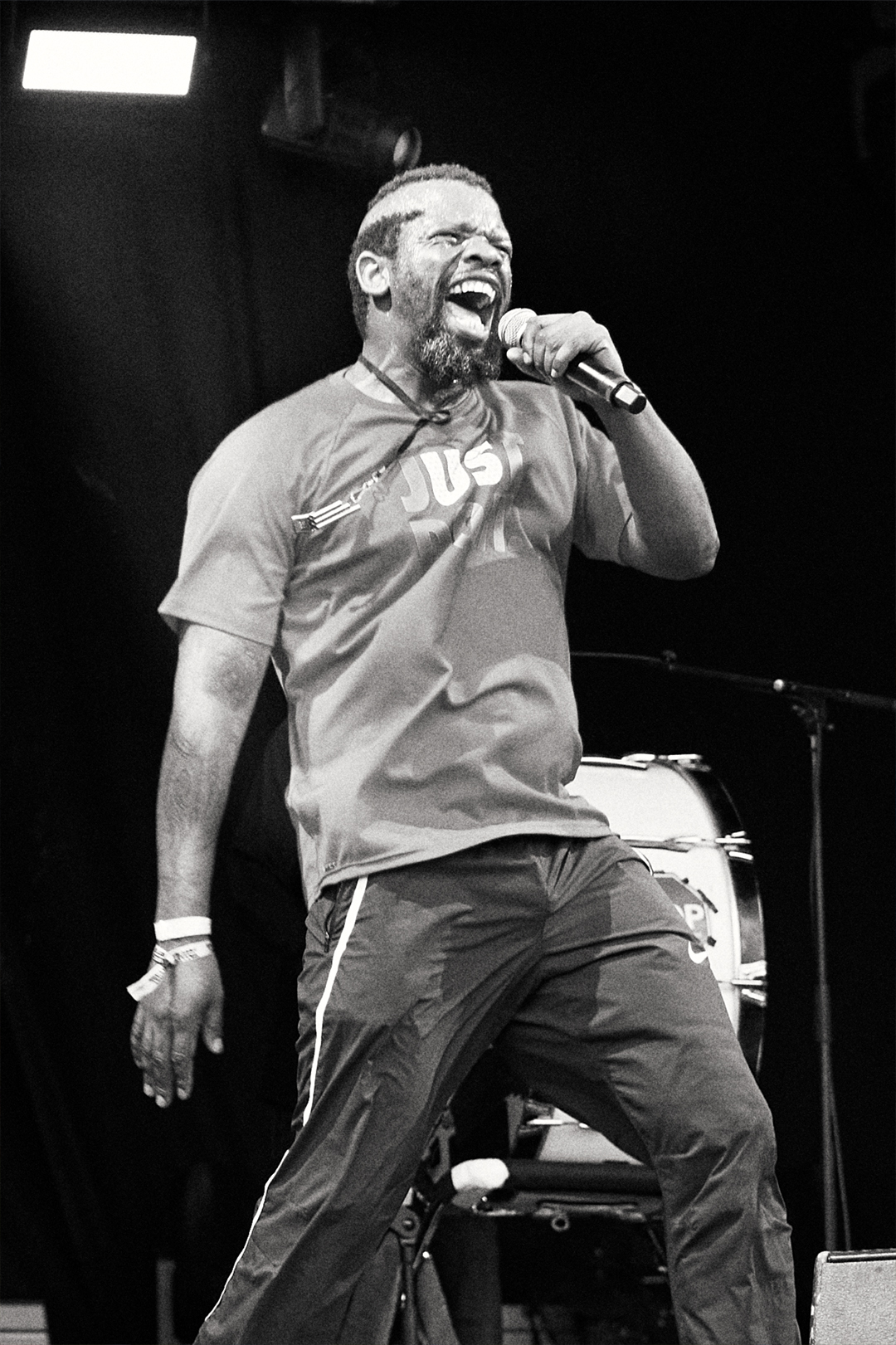

Not much comes close to the experience of watching BCUC live. The South African seven-piece have spent the past 20 years honing their raucous improvisatory sound, journeying from weekly open jams in their local Soweto parks to prime slots at the Glastonbury and Womad festivals. On stage, they weave 20- or 30-minute-long tracks into a trance-inducing tapestry, combining harmonised chanting with fierce, polyrhythmic drumming. Their audiences dance, jump and stare in awe, pummelled by the sound.

“You should at least watch one BCUC show in your life,” vocalist and bandleader Nkosi Zithulele says with a wide smile. “It’s good, spiritual and uplifting, but it will also mess you up because we cover a wide array of emotions. We can take you from being sombre to feeling ecstasy – and there’s chaos, too.”

Zithulele is biased when it comes to selling the vitality of his band’s live shows, but their hectic summer tour schedule speaks for itself. When we chat over video call, the band are in Bordeaux, France, halfway through a four-month European run of almost 60 dates, supporting the release of their most recent album, Millions of Us. They have been battling the continent’s heatwave while playing to packed crowds of sweaty revellers. “It’s a rollercoaster being on tour,” Zithulele says from his white-walled hotel room, his hands flailing to illustrate his point. “You miss home from week one but the adrenaline and joy of being on stage carries you through. Our mission is to communicate our culture, to show people that modern South African music is much broader and more unhinged than they ever thought.”

This lively, new music of South Africa has been having its moment in the global spotlight lately. From Johannesburg’s house-influenced amapiano and the free jazz of community-based labels like Mushroom Hour Half Hour, to the frenetic beats of Durban gqom, grassroots scenes are thriving and have gone on to be interpolated by the likes of Drake and Beyoncé in their latest releases.

“The internet has been very good to the South African music scene,” vocalist Kgomotso Mokone says, joining Zithulele and perching on the end of his bed. “Everybody in that space is creating music for themselves, music that they like. No one has been chosen, they are just getting recognition because they have built a vibe among themselves and their crew, something that other people can’t help but take notice of once they find it online.”

Yet, BCUC don’t think their jazz-influenced, wall-of-vocals psychedelia has as much potential for popular crossover. “We’ve never been part of any Joburg scene. We’ve always been on the fringes,” Zithulele says. “We’re a bunch of risk-takers, intentionally not refining our sound. If we want to start a song at an unreasonable ferocity, we will, because that’s what the music demands. It might mean that the journey has been long but the fruits are sweeter.”

Forming in 2003, BCUC’s journey to international acclaim has indeed been a slow burn. Zithulele and Mokone first met at high school in Soweto when Zithulele was interested in becoming a rapper and Mokone was studying saxophone. The pair soon bonded and began pulling other friends into a free-form ensemble exploring live instrumentation and South African traditional music.

“We raised each other,” Mokone says, nudging Zithulele playfully. “Most of us all live in the same neighbourhoods and initially there were 13 members of BCUC. We just wanted to play all the time and to be seen, so we would rehearse anywhere we could – most often in parks under trees.”

These long jam sessions soon became notorious and the band attracted a committed local following. “We were raised on chants – as South Africans, we can chant until the sun comes out. It’s a meditative, beautiful thing,” Mokone says. “What we wanted to do as a group was to infuse our music with this trance-like chanting, while making sure we weren’t repetitive. It was all about creating a sonic tapestry that could communicate emotions, without even needing to know or understand what was being said. People really responded.”

“Our mission is to communicate our culture, to show people that modern South African music is much broader and more unhinged than they ever thought” – Nkosi Zithulele

Taking on the name BCUC – Bantu Continua Uhuru Consciousness, or people continuing the freedom of consciousness – the group made it their mission to ensure their listeners and community were centred within their creativity. Keeping their shows at home free to attend or heavily subsidised, BCUC wanted to encourage other artists to follow their path, especially if they were from working class Black backgrounds. “We’re trying to show other bands in South Africa that this career is possible,” Zithulele says. “We are a blue-collar working band and our office is the stage. We earn the same money as professionals with a stable job back home, like teachers or nurses. We want to show artisans that you can do it too. You just have to dream.”

As well as inspiring other artists, BCUC are committed to using their music to challenge their country’s politicised racial dynamics, only a few decades on from the end of apartheid. “We don’t think of ourselves as a Black band in a white world. We just want to be an amazing band,” Zithulele says. “We don’t separate ourselves from our audience and that means that we have to build a connection between white bands and Black bands.”

Initially finding themselves sometimes segregated into playing shows for majority white audiences, while their white peers didn’t feel able to find Black audiences, BCUC took matters into their own hands and began to put on their own events. “We found ourselves divided, and while the white bands wanted to come to Soweto, they didn’t know where to play, so we’d book them and we’d show them the place and people,” Zithulele says. “They would see our Soweto and we would ultimately try to make people see that there can be a relationship between Black people and white people that isn’t employer-employee.”

In a country where 11 languages are spoken, these multi-band shows would see BCUC hosting groups who sang in Afrikaans – a language mostly spoken by the country’s white population – communicating messages that not everyone in the crowd would understand. “It’s no different to us playing in France tonight – how do you express yourself when the language isn’t there? How do you make the sound connect?” Mokone says. “We just want to play in front of different people, and different South Africans especially, and make sure that by the end of the show, they feel uplifted and know that new things are possible.” Or that a common understanding runs deeper than just language.

After spending the best part of a decade playing and hosting these local shows, BCUC appeared on the radar of French booking agent and Nyami Nyami label head Antoine Rajon who signed their debut album, 2016’s Our Truth. Across its four tracks, two of which run longer than 17 minutes, BCUC distil their live energy to maintain momentum even in the most ferocious settings, traversing the earthy funk of Yinde to the guitar-strumming yearning of In My Blues. 2018’s Emakhosini and 2019’s The Healing continue in the same narrative vein, with the latter featuring collaborations with Femi Kuti on the anthemic Sikhulekile and Saul Williams on the bass-pounding Isivunguvungu.

“Not everyone was a fan when we started,” Zithulele laughs. “Some people were like, ‘Come on guys, just make a short track. Do a normal song!’” That was a complaint shared by a minority, since the strength of their longform recordings brought bookings at festivals like Gilles Peterson’s Worldwide in 2017, and Glastonbury in 2019. And yet, the band kept on wondering what it would sound like if they did try to cut down their compositions. When Covid hit, they found they had the time for the experiments that would ultimately lead to Millions of Us.

With the shortest of its six tracks still running at a respectable five minutes, Millions of Us is a new frontier for BCUC. Harnessing punchy top-line melodies and driving, percussive grooves, the band maintain their signature cyclical chanting and propensity for a euphoric musical explosion within more compact structures. Featuring propulsive, endless crescendos and earworming melodies on tracks like Ntuthwane, Millions of Us is perhaps the closest the band will come to a radio-friendly crossover.

There is also a message behind this fierce music. “As one person, I come with all my ancestors, and when we combine with our audience, there are millions of us,” Zithulele explains. “We’re all in this life together and we have to look after each other – Covid showed us that much. It emphasised that this music we make is by the people, for the people.”

Making their music intrinsic to their sense of community, it’s clear that BCUC is a lifelong project and one that the band feels can only continue its slow burn. “We’ll be here for another 20 years at least,” Zithulele says, leaning into the camera. “If we were from money or white, we would be a legendary band by now. But we will have our time.”

For now, their time is coming to wow their French crowd, and Zithulele is already looking forward to giving the room a taste of the unexpected. With two decades worth of experience playing in their own lane, at a level of intensity few groups can match, it feels as if BCUC are well on their way to becoming a “legendary band” by virtue of their irrepressible live energy. “You never know what you’re walking into and that’s what gets us so excited,” he concludes with a laugh. “Some rooms you play and you’re not ready for that level of response. That’s when you need to go back for round two.”

Millions of Us is out now via On the Corner