This $400 kitchen bin eats your leftovers and promises to turn them into chicken food rather than landfill. A nicer-smelling kitchen and less waste are great, but not at this price.

At around 1AM on Sunday morning, my partner sat bolt upright in bed and whispered urgently, “There’s someone in the kitchen!” After listening sleepily for a few seconds to the muffled clunking noise, I replied, “No, there’s not; that’s just the smart bin eating an avocado pit.”

For most couples, this would have necessitated a further middle-of-the-night conversation, but for my long-suffering spouse, the word “smart” was all he needed to hear to roll his eyes and huffily go back to sleep.

The noise-making contraption was the Mill Kitchen Bin — a full-sized, sleek-looking Wi-Fi-connected trash can packed with sensors and an industrial-grade food grinder. It had hit a snag (a large pit) during its otherwise quiet nightly business of munching through its load of melon rinds, egg shells, coffee grinds, half-eaten peanut butter sandwiches, and chicken bones. Over nine hours or so, it worked on shredding, shrinking, drying, and dehydrating the food remnants we’d thrown in the 27-inch-tall, 16-inch-wide bin during the day, turning them into “food grounds” by morning.

The concept here is similar to the electric countertop “composters” you may have heard of — electronic gadgets that grind, dry, and dehydrate uneaten food. But instead of attempting to turn it into compost intended for your garden or houseplants, as those composters do, Mill wants you to ship the food grounds it regurgitates back to the company every month or so, where it turns it into food for chickens.

At least, that’s the plan. Mill CEO and co-founder Matt Rogers tells me they’re still working through some “R&D and regulatory processes” for the feed part. But the idea is that “Food is much more valuable than compost,” he says. “We should keep food as food.”

He’s not wrong. As with Roger’s prior efforts (which include the category-defining Nest Learning Thermostat), the Mill is designed to tackle a huge climate issue. This time, it’s household food waste instead of household energy use. “It’s a massive problem. We throw away about 40 percent of the food we grow, half of which comes from us at home,” he says.

Consequently, food is the most common item in landfills, where it gives off the greenhouse gas methane as it decomposes. It’s a big, little-discussed, global problem, which is a wildly massive issue to tackle with a pricey smart kitchen bin. “It’s this perfect blend of technology meets design meets climate,” says Rogers of the new invention. Mill provides an alternative if you don’t have the time, space, or expertise to manage a compost bin, or if you have all of the above but have nowhere useful to use the compost.

I’ve spent a few months with the Mill in my kitchen, and while there is good tech and design here, the bin in its current form is not the solution to food waste. What it is is a very expensive smart rubbish bin that will make you feel better if you can’t / won’t compost or are unable to make any other effort to reduce what you throw out.

You can’t buy the bin outright. Instead, it’s a subscription model, so you’re basically renting it. You either pay $396 a year ($33 a month) or $45 monthly plus a $75 bin delivery (for a total of $615 for the first year). If you reserve a Mill bin today, Mill tells me it should be shipped to you in about two months. There’s no minimum time commitment, and the monthly fee covers all parts, repairs, replacements, and costs / materials for shipping the grounds back. You don’t have to ship the grinds back, but you still pay monthly either way.

While the bin will reduce the amount of trash that leaves your house, there are cheaper solutions for managing your food waste responsibly, including proper meal planning, non-electric countertop compost bins (if you’ve nowhere to put your scraps, there are organizations that can use them), and municipal and private composting programs. But Mill’s selling point is ease of use, and it’s a lot easier and less smelly than any of the above.

Dropping food scraps into the pedal-operated Mill is as easy as throwing them in the trash, but unlike a regular trash can or countertop composting, the Mill isn’t messy, doesn’t smell bad (even with shrimp shells in there for three days), and never attracts flies.

For me, the main benefit was that I only had to empty it about once a month (an easy process), and because I was inputting less in my regular trash bin, that went out less often, too. Mill reports one customer who shipped a 25-pound box of food grounds back to them kept “8.5 standard trash bags out of the landfill.”

But, unless you can offset its cost by paying for a smaller garbage can from your municipality, Mill is a solution for rich people who care about the planet. Those of us who care about the planet but aren’t able to spend $33 a month for a more convenient way to do good and can’t recoup any costs from downsizing our garbage can are just going to have to keep sticking our food scraps in the freezer and lobbying the local council for better community composting.

We shouldn’t waste food, yet we do. My family of four wastes an unconscionable amount due to busy schedules, picky eaters, and a too-big refrigerator that hides leftovers until they walk out on their own.

We have chickens and a bunny rabbit, so fresh scraps from chopping veggies and fruits mostly find a happy home. But there is a very long list of things chickens can’t eat, including avocados, potatoes, onions, coffee grinds, and anything in butter, oil, or salt (so, most of what I cook).

However, the Mill can eat all these things, which made me skeptical about how Mill Industries will turn these food grounds into healthy chicken food for local farms. According to Mill, the grounds go through several processing steps to make them safe for chickens. “We’re able to test it and blend it to get the right nutritious ingredients,” says Rogers.

But it turns out this is a thing they haven’t actually done yet, at least outside of the research stages. I wanted to try out their chicken food on my chickens, and while Rogers told me I could feed them the grounds directly, the company is still “working to make them into a safe chicken feed ingredient.”

To create food for any creature, you need approval from the Food and Drug Administration and the version for animals, the Association of American Feed Control Officials (AAFCO). As no one has ever made commercial chicken food from household leftovers before (it has been done with restaurant and grocery store scraps), Mill needs approval for its process.

While it’s not there yet, the company is getting close. This week, AAFCO approved a new definition for animal feed ingredients made from Dried, Recovered Household Food. There are still more regulatory hoops to jump through, but Mill spokesperson Molly Spaeth tells me, “We expect the two additional procedural votes to be completed by January 2024 at the latest. We have started [chicken feed] production now and are distributing in an R&D capacity until we have that full clearance in January.”

I’m not intimately familiar with regulatory processes for animal food, but right now, Mill’s product doesn’t deliver on its core promise of turning your food waste into commercial chicken food. Until that’s a proven solution — i.e., the hens are happy — it’s basically a glorified trash compactor that you pay monthly for the privilege of using.

Hungry chickens aside, as a smart trash can, the Mill works well. It made disposing of my food waste easier than my nascent attempts at composting (which is not as simple as it sounds), and I felt less guilt dumping leftovers from my plate or chopping board in there than throwing them in the bin destined for the landfill.

The list of foods the bin can’t take is significantly smaller than things my chickens can’t eat — you shouldn’t put in large bones, hard shells, corn husks, rotten food, or copious amounts of sugar like a whole cake (who throws away a whole cake?!). There’s a handy list of dos and don’ts that attaches magnetically to the bin.

Unlike most of the tech in my smart home, the Mill required minimal attention. Open it with the foot pedal, discarded food goes in, the lid locks at 10PM each night, and the lengthy grinding begins (you can adjust the start time in the accompanying app). Setup was as easy as unboxing, popping in the bucket and large charcoal filter, and plugging it in — although I needed help as the whole contraption weighs a whopping 50 pounds.

You have to sign up for an account to use the Mill and provide your name and email. If you choose to send in the food grounds (which is optional), the company sifts through your garbage to remove any contaminants. Mill says the device and app collect diagnostic data necessary for operation. This includes data from internal sensors that measure humidity, temperature, weight, air intake and exhaust, grinder, and fan speed.

Mill says it also collects device usage data, such as when the lid is opened or closed, the weight of the matter put in the bucket, humidity inside of the bin, whether or not it’s connected to the internet, how long the bin runs for each time it runs (to model energy consumption), what time the bin runs, and whether the bin has jammed.

It’s not possible to opt out of sharing this data, but Mill says it’s secured “using industry-standard protocols both in transit and at rest.” Mill will delete your data upon request.

You have to connect the bin to the internet to set it up, but after that, a connection is not required for the bin to run. Mill says it does not sell user or usage data but will “share aggregated data with certain partners and may disclose personal information according to terms in its Privacy Policy.

Using the bin with its companion smartphone app required setting up an account with my email address. I then paired it via Bluetooth and connected it to my Wi-Fi. The app can send push notifications when the bin is full and if there are problems, and it is also where I could set what time the grinding would begin. It recommends 10PM, and I got a fright when I watched TV in the living room one night, and the bin made a very loud clunking sound as it locked the lid. The grinding process itself, however, is surprisingly quiet (avocado pits notwithstanding).

The bin doesn’t have to be online all the time, and connectivity isn’t required to use it. Its onboard sensors that detect weight, humidity, and moisture run using on-device algorithms to determine how long to grind and dry the food scraps and don’t rely on a cloud connection. However, connectivity helps keep track of the time it needs to automate the dehydration cycles and allows for firmware updates and tweaks to the algorithms.

While I was testing the bin, it received an update that shortened the drying time by an hour or so, ending around 6AM instead of 7AM. Mill also monitors things like the status of the charcoal filter to send a new one automatically and offers up troubleshooting tips in the app if a jam happens.

Subtle LED lights on the bin’s faux-wood lid tell you what it’s doing — grinding, mixing, locked and hot, or ready to be emptied. You can press and hold its single physical button to unlock it while it’s working to add extra scraps, although this process took a beat longer than was useful when you’re in the middle of making breakfast.

When the Mill got jammed, I learned about the other LED icon — two flashing red dots. This was my worst experience with the bin, and the troubleshooting steps the app took me through to try and clear it were sticky, gross, and unsuccessful. In the end, Mill overnighted a new bucket (the removable part, not the whole bin) and had me send my one back for “an examination,” a process included in the product’s warranty.

According to Spaeth, Mill determined the jam was likely caused by adding a bunch of old chard on top of an almost full bucket of overly dehydrated scraps, causing the grounds at the bottom to turn into cement. That firmware update that came a few weeks later and adjusted the drying time was designed to correct this problem so as not to turn the food scraps into powder. But the jam experience was so icky that had I been paying for the service, I would have canceled it on the spot.

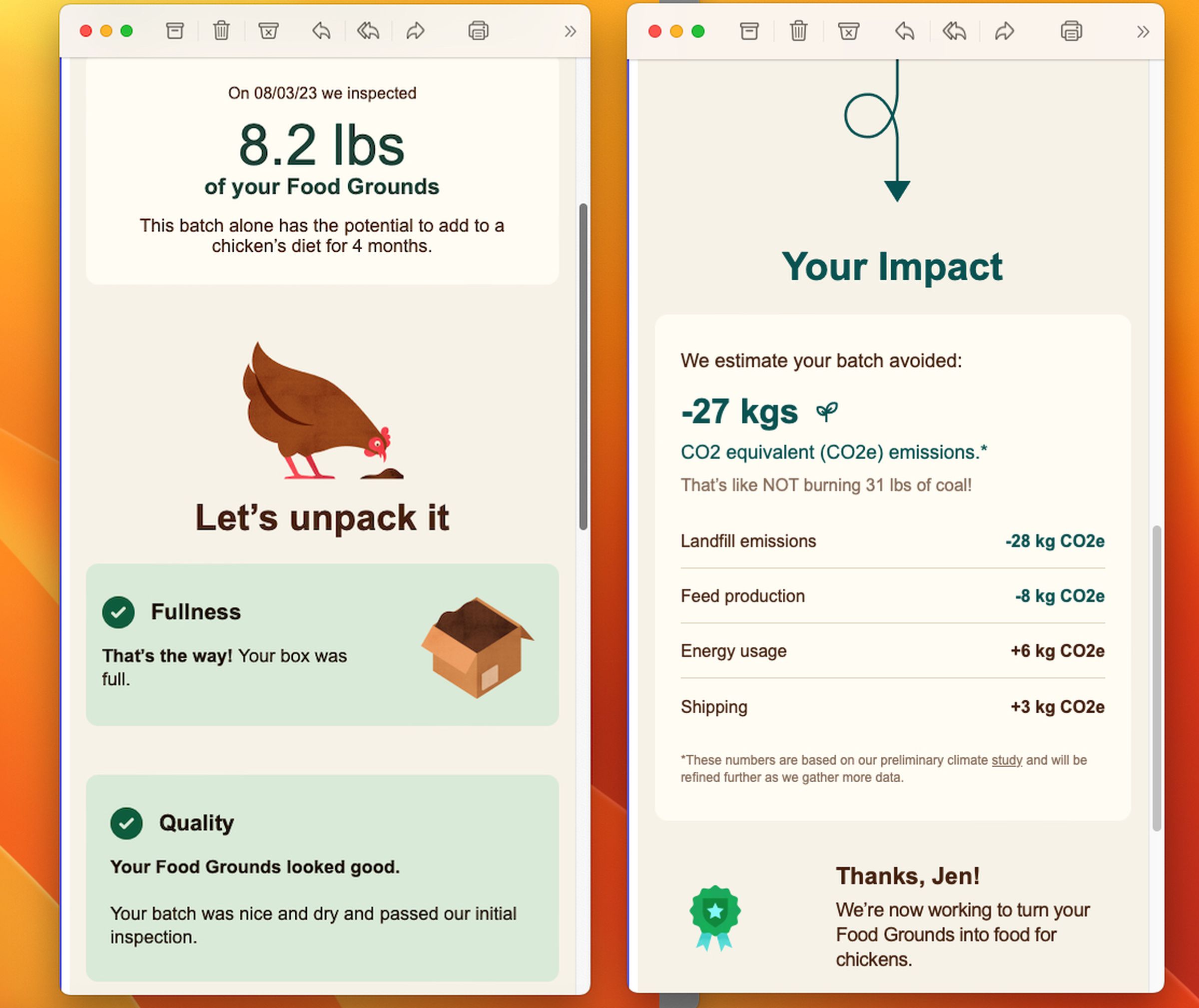

Thankfully, once the dark jam days were over, emptying the bin and sending the grounds off to Mill was simple. Everything you need for this is included in the monthly subscription price. I just scheduled my mail delivery person to collect the prelabeled box on his next visit using Mill’s app. This means no extra truck rolling to collect my box and my two months’ worth of food waste — which, based on how many fewer trips to the garbage cart I took, would’ve taken up around four trash bags of space on a diesel garbage truck — fit into a box smaller than my last Amazon delivery package and weighed just over 8lbs.

According to the report Mill sent me after processing my waste (not a sentence a tech reviewer ever expects to write), I potentially saved -27kgs on CO2 equivalent emissions by using the bin. This included offsetting the energy use of the bin and the shipping footprint. This impact report is similar to the home report a Nest thermostat sends estimating energy saved. This type of positive reinforcement has been shown to help people change their habits. For Rogers, that’s where he sees Mill’s potential success, fundamentally altering people’s daily behaviors.

As it stands, though, this product feels more like a proof of concept. Ultimately, food waste is a problem too big for a Silicon Valley startup to solve singlehandedly. Solutions need to come from municipalities. Approximately 5 percent of US cities currently have a green bin program for food — something that is more common but still not prevalent in Europe. Even when Mill’s $400-a-year bins do effectively close the nutrient food cycle by producing commercial chicken food, we need better local solutions. If Mill is still shipping garbage across the country, then greenwashing accusations start to hold water.

Rogers recognizes this and makes it clear that how Mill is starting is not how it plans to scale. Mill has already partnered with several cities and has plans for more. Mill’s current solution is imperfect, but it does offer a potential alternative to existing systems that do too little. If Mill can scale to provide a viable infrastructure locally — where my food grounds are delivered to a local processing center, and the resulting chicken food goes to nearby farms, that seems like a win-win.

But that is a very big If. As it stands, my kitchen scraps are flying 3,000 miles or so from South Carolina to Mill’s only feed facility in Mukilteo, Washington, and so far, no local chickens have consumed a grain.

I enjoyed using the Mill — I like how it looks, and the convenience promise paid off — but I won’t pay $33 a month for it, and I doubt there are many people who will. Is it better than throwing your discarded food into the regular bin or down the garbage disposal? Yes. At a minimum, and chicken feed aside, the Mill bin dramatically reduced the volume of waste leaving my house, resulting in less space taken up in the landfill and that big diesel garbage truck.

But that just isn’t a compelling enough payoff for most people to invest monthly in a smart kitchen bin. It’s no 15 percent off your energy bill, as the Nest promises, which is a hard enough sell for a device that costs half the amount this bin does.

The experience did make me more aware of how much food we waste. But rather than pay for a fancy device to fix that problem, I’m determined to do a better job of meal planning and eating my leftovers in a timely fashion.

If the promise of the food grounds becoming chicken food pans out and if Mill can scale to a point where municipalities offer these bins to their taxpayers for free or reduced costs, similar to how energy companies give rebates on smart thermostats, I can see more value. If they also eliminate the cross-country shipping issue, that would be even better. But today, it feels like an over-engineered solution to an enormous problem that a few thousand people who can pay for the privilege of feeling better about their waste management just isn’t going to impact.

Photos and video by Jennifer Pattison Tuohy / The Verge

You need to register for a Mill account using an email address to use the Mill app (Android or iOS) and agree to the following:

In total, using the Mill requires two mandatory agreements.