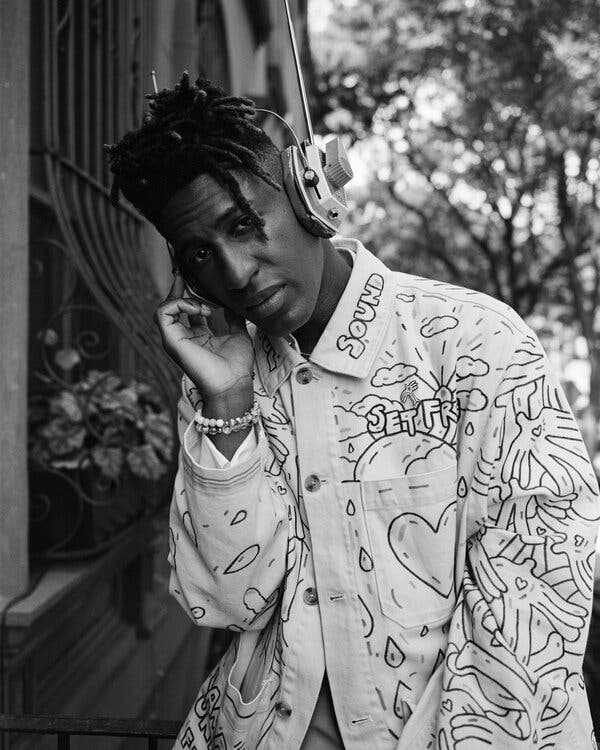

Nothing is simple when it comes to Jon Batiste, the pianist, television personality, New Orleans musical scion and jazz-R&B-classical savant.

He spent seven years as the smiling, melodica-toting TV bandleader on “The Late Show With Stephen Colbert,” yet found some of his widest acclaim for solemn protest performances in Brooklyn after the murder of George Floyd.

He beat Olivia Rodrigo, Taylor Swift and Billie Eilish for album of the year at the Grammys in 2022, despite his “We Are” having just a fraction of their sales — and then presented “American Symphony,” a Whitmanesque canvas of funk, Dixieland jazz, operatic vocals and Native American drums at Carnegie Hall.

Now comes Batiste’s most commercial project yet: “World Music Radio,” an album with guest appearances by Lana Del Rey, Lil Wayne and the K-pop girl group NewJeans, made with a team of producers behind hits for artists like Justin Bieber and Drake, with tightly woven hooks that were engineered to fit on any Top 40-style streaming playlist.

But of course “World Music Radio,” which comes out Aug. 18, is no standard pop release. It’s also a fantastical concept album that challenges music’s provincial genre borders, with a message of open-armed inclusivity for a fractured political era. The album’s central character, a timeless interstellar being named Billy Bob Bo Bob, curates a potpourri of the far-flung musical languages of Earth and transmits it to the cosmos with chuckling, Daddy-O commentary, like Doctor Who crossed with Wolfman Jack.

“He’s a D.J., he’s a griot, he’s a storyteller, he’s a unifier, he’s a rebel,” Batiste told me, describing the character of Billy Bob Bo Bob. “He’s a disrupter.”

That’s also as good an encapsulation as any of the 36-year-old Batiste himself, who can’t easily be pinned down to any single role, or genre, or corner of the music market.

In his own eccentric way, “World Music Radio” is Batiste’s interpretation of what mainstream pop is or should be, in which high-energy electronic dance beats coexist with reggae, Afropop and old-fashioned piano torch ballads. “Be Who You Are,” the first single, has lyrics in English, Spanish and Korean, and its high-tech, partially animated music video, produced through a brand deal with Coke, features Batiste, the Latin pop star Camilo, the rapper JID and the members of NewJeans all vibing alongside each other.

Yet in discussing the album, Batiste was almost totally cerebral, speaking in long, eloquent, practically unsummarizable paragraphs about his mental and creative processes. The album’s origin, he said, was partly philosophical, as he mused on the connections and divergences between “the horrendous idea of what we call ‘world music’” — local traditions viewed through a condescending Western lens — “and the narrow diameter of what’s considered popular music.”

“So then, world music,” Batiste added, shifting professorially on the living room sofa of his airy and immaculate Brooklyn brownstone. “What if we could reimagine that term? What if we could reinvent? What if we could use it as a prompt to expand the diameter of popular music?”

In conversation, he mentioned influences that included some of the most popular cultural productions of modern times, like Pink Floyd’s “The Dark Side of the Moon” and the “Godfather” films. Jamie Krents, the president of his label, Verve, said that Batiste had cited Michael Jackson’s “Thriller” as another reference point.

“He wanted to make music that was approachable to the largest possible audience without compromising,” Krents said.

Still, it is hard to imagine Jackson summarizing his goals for “Billie Jean” or “Beat It” in quite the same way that Batiste does for “World Music Radio”: “By listening to it and experiencing it,” he explained, “you have a realization about self, about community, about humanism, that leaves you in a state of bliss and a hyper-consciousness.”

AS BATISTE SEES IT, “World Music Radio” is the culmination of a career that has long snaked through supposedly disparate traditions and audiences.

Batiste grew up in Kenner, La., part of a family with deep musical roots in New Orleans, and he spent his teenage years playing late-night gigs in the French Quarter with his friend Trombone Shorty, then rushing to high school classes in the morning. He earned bachelor’s and master’s degrees from Juilliard and became a fixture around New York with his band Stay Human, especially for what he called “love riots”: spontaneous, Pied Piper-like performances of “You Are My Sunshine” or Lady Gaga songs that took place on the street or in the subway, interrupting the daily grind with flashes of joy.

At the same time, with his 2013 album “Social Music,” he began to develop a brand of activism that emphasized music’s power to find common ground amid ever-widening political polarization.

“Inclusive is not even the right word,” Batiste said of his approach. “It’s more, OK, we’re coexisting as human beings on Earth. We’re not a monolith. But underneath it all, we’re the same. That’s not something that can be interpreted in the binary climate that we’re in now.”

In 2015, Batiste and Stay Human became the house band on Colbert’s new CBS show, where Batiste performed comedic musical skits but had little outlet to express his broader political or social views. And, with over 200 shows a year, he also couldn’t tour — something that, incredibly, Batiste has never done as a headlining act.

“We Are,” which was begun in late 2019 and completed the following year at the height of the Covid-19 pandemic, became Batiste’s vehicle for protest and for communicating the wider social ambitions of his music. Although the album had barely registered in the marketplace, Batiste became the surprise top nominee for the 64th annual Grammy Awards, getting eight nods for “We Are” and three more for the movie soundtrack “Soul.” (The score for “Soul” also won Batiste, Trent Reznor and Atticus Ross an Oscar.)

At the same time, Batiste’s longtime partner, Suleika Jaouad, had spent years struggling with cancer and writing about it in The New York Times. The day the Grammy nominations were announced, Jaouad began a round of chemotherapy. “At certain points of her treatment,” Batiste said, “her immune system was so compromised that we couldn’t be in the same room.”

They married last year, and after a bone-marrow transplant, Jaouad’s health has improved enough that they recently took a vacation in Europe. “A major, major milestone,” Batiste said.

When “We Are” took album of the year, Batiste became the latest piñata for critics of the entire Grammy system, who pointed to his victory as a sign of an insider-controlled process out of touch with music’s dominant trends. Yet it also represented a necessary tension between artistic excellence, as judged by fellow musicians, and the pressure to reward commercial success. For another example, just look at the last Black man before Batiste to take the top prize: Herbie Hancock, back in 2008.

After his Grammy and Oscar wins, Batiste decided to leave Colbert’s show. Freed of that work, he now describes “World Music Radio” as his return to the concepts he explored a decade ago on “Social Music” — and imagined himself as Odysseus from Homer’s “Odyssey.”

“It’s the hero’s journey we always talk about,” Batiste said. “It feels kind of like, wow, I came back to where I was 10 years before, but now everything’s different, even though I’m in the same place that I was. I’m home, so to speak. But everything’s different.”

Colbert, in an interview, said that when Batiste approached him about leaving, “he didn’t have to tell me why.”

“But I did say I can understand why you would want to take this opportunity at this moment and go full-bore,” Colbert added. “I know that feeling very well: Give me the ball and see how fast I can run.”

THE MUSIC ON “World Music Radio” had its genesis, Batiste said, when he crossed paths with the producer Rick Rubin in Italy a few months after the Grammys. Rubin offered him use of Shangri-La, his beachside studio in Malibu, Calif., and Batiste headed there in August 2022 for a month of immersive work with a crew of producers and artists who came and went, generating what Batiste said were the kernels of upward of 125 songs.

Among Batiste’s collaborators there was Del Rey, who worked with Batiste on “Candy Necklace,” from her latest album, “Did You Know That There’s a Tunnel Under Ocean Blvd,” and she joins him on “Life Lesson,” a melancholy duet on “World Music Radio.”

The producer Rogét Chahayed, who has worked with Doja Cat, Drake and others, said he headed to Shangri-La after getting a surprise invitation from Batiste via Instagram. The sessions, he said, were spontaneous and fruitful, with Batiste sometimes kicking off hours of improvisatory jams after simply being inspired by a synthesizer tone.

“It was just like magic in the room,” Chahayed recalled. “It was right around evening time, the sun was setting over the ocean. I was like, this doesn’t happen often, in the kind of sessions that we usually have in these freezing cold studios with no windows.”

After those sessions, Jon Bellion, a pop performer and producer who has worked with Maroon 5 and the Jonas Brothers, collaborated with Batiste on a process he dubs “Batistifying” the material — combing through piles of half-finished material and whittling it down to a finished, coherent product.

With a deadline from his label looming, Batiste said, he felt that the album was not coming together until he sat in his basement studio in Brooklyn and listened to a vocal track sent by a Spanish singer, Rita Payés. She contributes to “My Heart,” a sepia-toned Latin ballad in waltz time on which Batiste channels Ibrahim Ferrer of the Buena Vista Social Club. Hearing Payés’s voice transmitted over a speaker, Batiste said, instantly suggested the album’s concept.

“It sounds like it’s coming out of a radio that’s sitting on top of the bar at a cafe in Catalonia, Spain,” Batiste said. “The working title up until that point was ‘World Music.’ And it was like, ohhh, ‘World Music Radio.’” He worked through the night to put together a rough version of the album, dreaming up Billy Bob Bo Bob as a narrator who segues between tracks and sometimes chirps in with an approving voice-over.

Another collaborator that Batiste pursued was the smooth-jazz saxman Kenny G. Batiste described him with a certain detached curiosity as a fellow artist who has one foot in jazz and another in pop, who has carved out a hugely successful niche but faced unending waves of critical vitriol.

“Anybody who’s talked about with that kind of extreme disdain,” Batiste said, “I always want to study.”

On the track “Clair de Lune,” which opens with an obscure sample from an old French folk album, Kenny G contributes a minute-long solo that is busier and more harmonically dense than his usual hooks, but with a singing tone that is instantly recognizable.

In an interview, Kenny G said that Batiste had asked him about the polarized reactions to his work.

“You’ve got to play what sounds good to you, and feels good to you,” Kenny G recalled telling him. “Lucky for you, there’s a big audience that seems to like what you do. Then you really don’t have to apologize for that.”

WHEN ASKED ABOUT his commercial hopes for “World Music Radio,” Batiste was typically circuitous and nuanced, saying that on one hand, he wants to compete with stars like Taylor Swift for top chart positions, but he also recognizes that his take on popular culture is more conceptual and abstract. He was most straightforward in saying he couldn’t wait to head out on tour.

He seems most prepared for any reaction to his social commentary on the album. “Love Black folks and white folks,” Batiste sings on “Be Who You Are.” “My Asians, my Africans, my Afro-Eurasian, Republican or Democrat.”

Even that simple message of openness and acceptance is relatively rare in an era when many pop stars shrink away from any social commentary at all, out of fear of alienating part of their audience and sacrificing clicks. It’s a risk Batiste is determined to take.

“To say I love everybody, including Republicans — as a Black guy, I don’t know how that could go,” he said. “That shouldn’t be something that’s frowned upon or looked at in a way that probably to some seems like, ‘Oh, he’s not really clear on what’s important.’”

“It’s radical today to love everybody,” he added. “We are in a time that there’s more of a pressure to make people into the other, and to dehumanize them in the process. But the act of removing a certain baseline of humanity in how we approach living amongst each other, that should be radical. That should be the thing that is disruptive.”