![Cheongdam Fashion Street in Gangnam District, southern Seoul [KIM SANG-SEON]](https://www.wazupnaija.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/why-why-do-koreans-love-luxury-brands-so-much.jpg)

Cheongdam Fashion Street in Gangnam District, southern Seoul [KIM SANG-SEON]

In Korea, the Chanel Medium Classic Flap Bag priced over 14 million won ($10,700) is famously known as the “wedding guest bag” due to its popularity among attendees who prefer luxury bags for weddings. Likewise, the two-million-won Louis Vuitton Speedy 30 bag is dubbed the “three-second bag” as it can be spotted every three seconds on the streets.

Kim, a 28-year-old office worker, is currently on the hunt for a high-end designer bag for her university friend’s upcoming wedding next month. Luxury brand bags hold significant cultural importance in Korean society, especially during events like weddings, where they serve as a means to showcase social status and success.

However, Kim’s ambitions clashes with the weight of a significant debt burden, consisting of 50 million won in credit loans for her recent home acquisition and an additional 4 million won in credit card installments for car insurance.

“Although my friends won’t judge me for not owning a luxury bag, I can’t help but feel a bit down about the sight of everyone else carrying a designer brand but myself,” Kim sighed.

Michelle Park, a 42-year-old residing in the United States, recently visited Korea and was taken aback by the prevalence of Moncler-wearing individuals on buses and subways.

“I was really surprised to see so many people wearing Moncler in the winter, on buses and subways,” Park said. “If you don’t know the brand, you’d wonder what it is that everyone is wearing.”

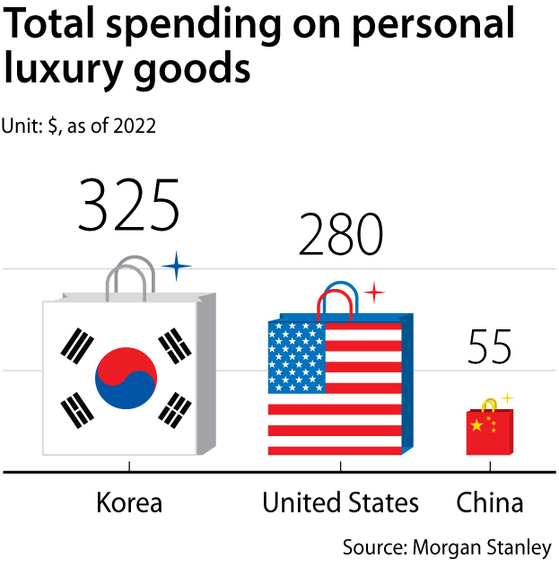

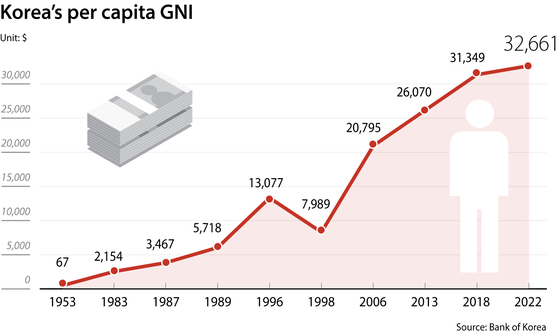

Korea stands out as the world’s largest spender on luxury goods, with a population of 51.7 million and a land area smaller than Kentucky. In 2022, Koreans ranked first globally in per capita spending, splurging an average of $325 on luxury items, totaling $16.8 billion. It surpassed economies like the United States at $280 and China at $55.

Even amidst the Covid-19 pandemic, the allure of luxury brands remained strong, with Korean luxury goods sales resilient in 2020 compared to the global decline.

For brands like Moncler, revenue in Korea “more than doubled” in the second quarter of 2022 compared to pre-pandemic levels. The Richemont Group, the owner of brands like Cartier and Piaget, reported that Korea was one of the few regions where sales saw a “double-digit” increase in 2022. Prada, while facing a 7 percent retail performance decline in the Asia Pacific region due to China’s lockdowns from the Covid-19 pandemic, said it managed to compensate for the drop through strong sales in Korea and South East Asia.

A study conducted by Bernstein, a US investment firm, found that Seoul stands as a global luxury brand haven with 221 outlets, ranking second worldwide just behind Tokyo.

So, why do Koreans have a particularly strong affinity for luxury goods?

A blend of desire and economic growth

Korea’s passion for luxury goods is deeply intertwined with its historical journey of desire and economic prowess.

“The expansion of Korea’s luxury market is closely connected to Korea’s globalization,” Seo Won-seok, an economics professor at Kookmin University, told the Korea JoongAng Daily. “Korea’s economic strength has considerably grown since the mid-1980s and overseas travel became allowed — enabling Koreans to explore the world of foreign luxury goods.”

Back in the ‘70s, strict import restrictions through high tariffs made foreign products, especially luxury items, a rarity.

However, a pivotal moment emerged with the 1988 Seoul Olympics, when import tariffs on clothing and shoes were relaxed, paving the way for a flood of foreign brands into Korea. Louis Vuitton’s entry into Lotte Duty Free in 1984 and the establishment of Louis Vuitton Korea in 1991 were significant milestones.

The liberalization of overseas travel played another crucial role. Surprisingly, until the early 1980s, leisure travel abroad was nearly impossible due to limited passport issuance. However, in 1989, travel restrictions were lifted, and outbound travelers surpassed one million, exposing Koreans to fashion capitals like Paris and Milan, igniting their fascination with luxury.

Driving luxury brand success is the purchasing power of consumers. During the late 1980s and mid-1990s, Korea experienced an economic boom, witnessing per capita GNI soaring from a mere $1,870 in 1980 to surpassing $10,000 by 1994. The growth rate of per capita GNI reached double digits annually until the brink of the 1997 Asian financial crisis.

“With an influx of imported consumer goods, those who experienced luxury found it hard to settle for less, driving their persistent pursuit of foreign luxury brands,” Prof. Seo said.

The conspicuous display culture

Korea’s luxury market has experienced rapid growth, partly influenced by its distinct cultural characteristics, including conspicuous display culture.

Conversations about personal wealth and earnings — even about performance bonuses at different organizations — are common in Korean online communities and even make news headlines, highlighting the significance of economic status.

In Korea, the possession of luxury items is often seen as crucial to avoiding feelings of social insignificance. People strongly link owning luxury goods with showcasing their worth, leading to a sense of defeat or deprivation if they lack such items.

“There is an obsession among Koreans, especially women, to own at least one luxury item if they are in their 30s,” said Kim Soo-jin, a 36-year-old housewife living in Seoul. “Having luxury goods reflects the economic status, and many would even consider using knock-offs as an alternative.”

In fact, the term “myeongpoom” in Korean, referring to luxury goods, has its hanja (Chinese characters) origins in the idea of “masterpiece” or “master-work.” However, to avoid potential resistance to the term “luxury goods” when they were initially introduced in Korea, a Louis Vuitton Korea marketing team purposely used “myeompoom” to provide a firm sense of superiority and judgment criteria, making people perceive it as an overwhelmingly superior product or item.

A survey conducted by McKinsey revealed that displaying luxury items is widely accepted in Korean society, with only 22 percent of respondents considering it not a good thing.

![Amidst Chanel's price increase announcement, customers queue up in front of Lotte Department Store in Jung District, central Seoul, on May 13, 2020. [YONHAP]](https://www.wazupnaija.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/why-why-do-koreans-love-luxury-brands-so-much-3.jpg)

Amidst Chanel’s price increase announcement, customers queue up in front of Lotte Department Store in Jung District, central Seoul, on May 13, 2020. [YONHAP]

The “Veblen effect,” an economic phenomenon that occurs when the demand for luxury increases as their prices rise, combined with the impact of social networks and word-of-mouth, created a natural connection to luxury goods. For example, Chanel’s continuous price increases in the past years sparked frenzied consumer interest in Korea, resulting in long queues forming outside department stores even before their opening time — known as “open runs.”

“Korea’s high social and cultural homogeneity, along with its dense residential communities, has fostered a culture of comparing with neighbors in daily life,” explained Kang Joon-man, a professor at Jeonbuk University, in a media interview. “The ‘neighbor effect,’ which hinges on finding life satisfaction through comparing oneself to others, plays a significant role in driving the desire for owning luxury goods.”

“As the Korean economy experienced rapid growth during the past 30 to 40 years, it became important to ascend the social ladder,” said Lim Woon-taek, a sociology professor at Keimyung University. “Thus people are feeling the need to keep up with their neighbors, such as owning foreign brand cars, which is a trend more pronounced compared to other locations such as Europe.”

Youth embracing luxury goods as ultra-low birthrate deepens

In the first half of 2023, major domestic department stores are finding that nearly half of their luxury brand consumers are Millennials and Gen Z. The percentage of young people in their 20s and 30s accounted for 41.7 percent at Shinsegae Department Store; Lotte Department Store at 45 percent; Hyundai Department Store at 42.2 percent; and Galleria Department Store at 39 percent.

Korea faces challenges with a significant low birth rate issue and a growing number of young Koreans choosing to opt-out of marriage. With no immediate family obligations, the trend of self-reward among the youth through luxury purchases is on the rise.

Thirty-two-year-old Jeon, who is single, is an example of this trend. Despite her monthly salary of approximately 2.4 million won after taxes, Jeon recently purchased two Chanel and two Saint Laurent bags, viewing them as an “investment” in herself.

“They may have been costly compared to my assets,” admitted Jeon, “but I still see it as a rare opportunity to indulge in self-care.”

The surge in property prices is also influencing luxury consumption trends among the younger generation. With the dream of homeownership seemingly out of reach, many young Koreans have redirected their income towards luxury treats instead of saving for a home. This shift has made luxury bags and items more appealing as a form of stress relief and personal enjoyment.

The 20s and 30s cohort showcases a distinct consumption pattern compared to previous generations. They prioritize their own happiness and values, engaging in rational consumption. Embracing a flexing culture that showcases success and wealth, they confidently spend on brands and products that highlight their self-worth.

![Gucci held its Cruise 2024 Fashion Show at Seoul's Gyeongbokgung Palace on May 16. Preceding this, Dior hosted a fashion show at Ewha Womans University in April 2022, and this year in April Louis Vuitton presented its first fashion show at Jamsu Bridge over the Han River in Seoul. [GUCCI]](https://www.wazupnaija.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/why-why-do-koreans-love-luxury-brands-so-much-5.jpg)

Gucci held its Cruise 2024 Fashion Show at Seoul’s Gyeongbokgung Palace on May 16. Preceding this, Dior hosted a fashion show at Ewha Womans University in April 2022, and this year in April Louis Vuitton presented its first fashion show at Jamsu Bridge over the Han River in Seoul. [GUCCI]

K-pop influences the global luxury brand market

The growing domestic luxury market size, coupled up with the popularity of Korean culture, is now attracting renowned overseas names.

“Many are literally ‘lining up’ to host pop-up stores in Seoul’s department store branches,” said a spokesperson from Hyundai Department Store.

Notably, the Italian fashion brand Prada is set to introduce Prada Mode, a cultural event combined with a social club, in September. Other luxury brands like Gucci, Louis Vuitton and Dior have expressed their affection for Seoul by hosting fashion shows at iconic locations, such as Gyeongbok Palace, Jamsu Bridge and Ewha Womans University.

The influence of Korean content as a major Asian market plays a crucial role in attracting global luxury brands.

Brands like Louis Vuitton and Chanel have chosen popular K-pop idols such as BTS and Blackpink as their global ambassadors due to the country’s high consumer loyalty and influencer culture.

Nick Bradstreet, the head of Asia Pacific Retail at Savills, said in an interview with a Korean media outlet in January that Korea is making significant strides in the luxury industry, surpassing Japan and China to become the most important market in Asia. Savills, a London-based real estate advisor, has been involved in the global expansion of major luxury brands like Chanel and Louis Vuitton.

With its K-pop influence, Broadstreet stressed that Korea has become a “vital barometer” for the success of global luxury brands in the Asian market, while adding that existing luxury brands are considering expanding their presence in Korea post-pandemic, while new brands are exploring entry opportunities into the market.

![Members of the K-pop girl group NewJeans strike poses at a Chanel pop-up store event held in Seongdong District, eastern Seoul, on Aug. 2, 2022. Danielle has been appointed as a global ambassador for Burberry, Hyein was selected as a Louis Vuitton ambassador, Minji as a Chanel ambassador and Hani as a Gucci ambassador. Three out of five members are minors. [NEWS1]](https://www.wazupnaija.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/why-why-do-koreans-love-luxury-brands-so-much-6.jpg)

Members of the K-pop girl group NewJeans strike poses at a Chanel pop-up store event held in Seongdong District, eastern Seoul, on Aug. 2, 2022. Danielle has been appointed as a global ambassador for Burberry, Hyein was selected as a Louis Vuitton ambassador, Minji as a Chanel ambassador and Hani as a Gucci ambassador. Three out of five members are minors. [NEWS1]

While this trend is attractive to brands, there is also concern about the lowering age of brand ambassadors fueling the interest of teenagers in luxury goods.

Young K-pop idols have become luxury brand ambassadors, including members of the group NewJeans: Minji, Hyerin, Hani, Danielle, and Haein, who have collaborated with major brands while three of the band are still minors. The rise of these young idols as luxury ambassadors is gaining strong support from elementary school students, even influencing their fashion choices.

“K-pop idols’ appearances in luxury fashion on social media and other platforms make it easier for children to become aware of these brands and sometimes even discuss them,” said fifth-grade elementary school teacher Kim Mi-hyeon. “A colleague teacher who teaches in Gangnam frequently notices students wearing luxury brands like Moncler, Burberry and Fendi, and there are more such students as they get into middle school and high school.”

![Shoppers buy goods at a Daiso store, a low-cost chain. [DAISO]](https://www.wazupnaija.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/why-why-do-koreans-love-luxury-brands-so-much-7.jpg)

Shoppers buy goods at a Daiso store, a low-cost chain. [DAISO]

Divergent consumer behavior in the face of rising prices

As everyday prices continue to soar, consumer patterns in Korea are taking an interesting turn. On one end of the spectrum, there is a surge in luxury purchases, with people flocking to department stores to indulge in high-end goods. Simultaneously, on the other side, a different trend is emerging, where individuals are gravitating towards the representative affordable brand, Daiso, to find budget-friendly items.

Daiso, a low-cost chain, has become a haven for those seeking pocket-friendly options — offering some 32,000 products across 20 categories, all priced at 5,000 won or less. The majority of its inventory consists of items priced between 1,000 to 2,000 won.

Jang Ji-hyun, a 25-year-old working professional, revealed that she frequents Daiso at least once in a week to buy everyday essentials at a bargain.

“I recently purchased a scouring pad and masking tape,” Jang said. “The reason behind my choice was purely the affordable price.”

Experts have coined the term “ambisumer,” a shortened term for ambivalent consumer, to describe the consumer trend currently unfolding. This trend sees people boldly spending on goods they highly value, such as luxury items, while becoming more prudent with discretionary expenses amidst inflation. While essential goods are primarily determined by their price due to little variation in preferences or quality, luxury goods are now evaluated based on the brand’s aesthetic and the psychological value they offer.

“The consumption patterns of particularly young people in their 20s and 30s are characterized by their willingness to spend on products that align with their tastes and their emphasis on experiences,” said Lee Eun-hee, a consumer science professor from Inha University. “As a result, they are emerging as the primary consumers of luxury goods and omakase [chef’s choice] dining experiences.

“They occasionally indulges in high-end luxury goods, not only for the quality but also to savor experiences that resonate with a higher social status, but at the same time, they are quite mindful of cost-effectiveness when making everyday purchases,” she added. “This trend of divergent consumer behavior, where people seek affordable options amidst high inflation while still splurging on luxury items, is expected to persist in the foreseeable future.”

BY SEO JI-EUN [seo.jieun1@joongang.co.kr]

![[WHY] Why do Koreans love luxury brands so much?](https://www.wazupnaija.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/why-why-do-koreans-love-luxury-brands-so-much-1050x600.jpg)