BoF’s Imran Amed and Bernstein analyst Luca Solca discuss the factors that have driven unprecedented growth at fashion’s biggest companies — all, incidentally, based in Paris — over the past decade. The conversation touches upon booming luxury sales in a turbulent world and the world’s wealthiest man, LVMH chairman Bernard Arnault. Amed and Solca provide measured perspective, and a little prediction.

Jonathan Wingfield: Is it too simplistic to say that Paris is, more than ever before, the centre of luxury fashion?

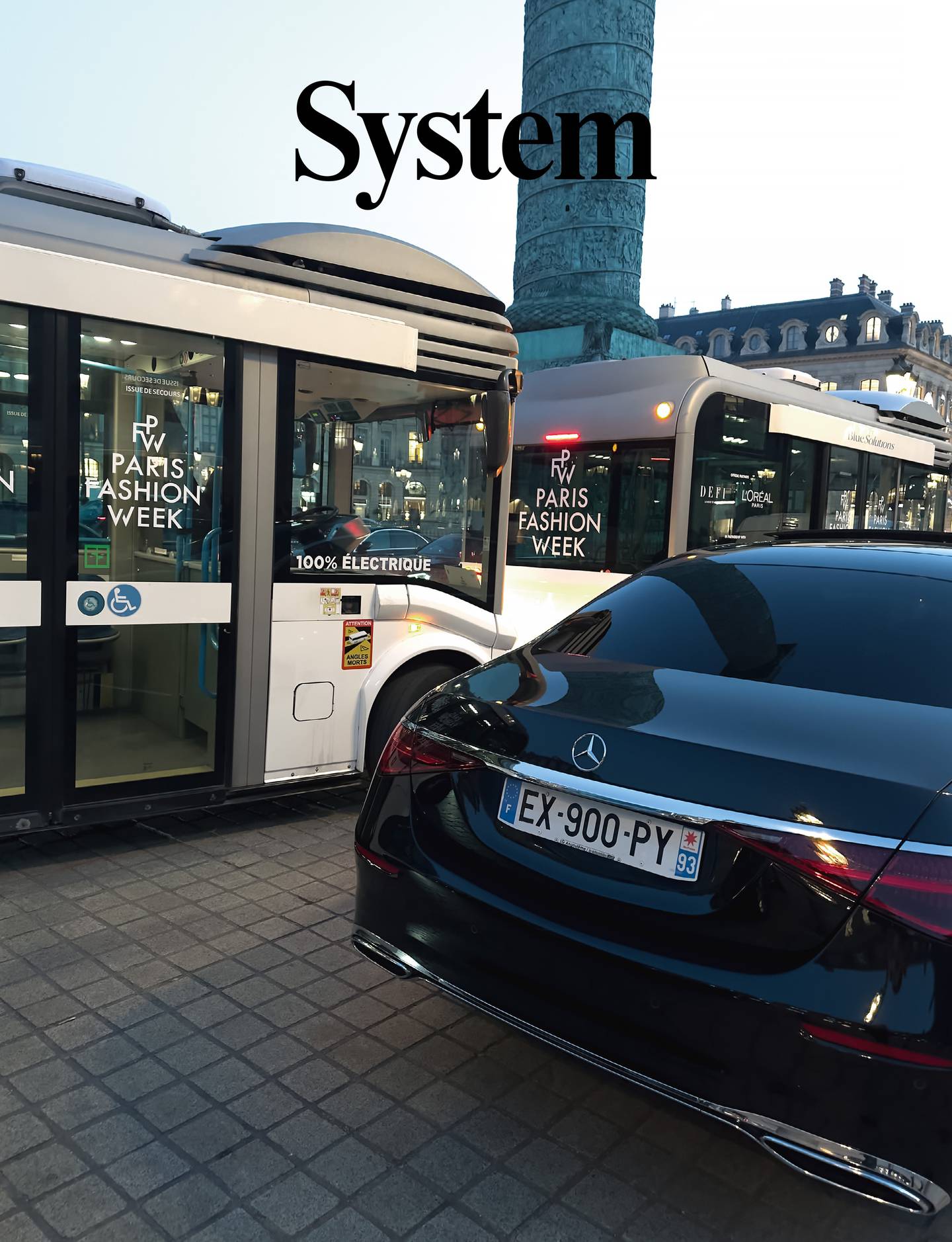

Luca Solca: Paris is all the more central in the grand scheme of things, because the luxury and fashion industry has continued to consolidate, and the primary grabbers of that are the Parisian companies and conglomerates. If we look at LVMH, Kering, Chanel, Hermès, they have an even greater domination of this industry today than they had 10 years ago. As a consequence, they are escalating on a number of fronts, including building extraordinary flagship stores in Paris, which is now head and shoulders above anywhere else for the size and quality of its flagship stores. Just look at what Dior has done on Avenue Montaigne or Vuitton on Place Vendôme. These are incredible developments that were just not on the map a decade ago.

Look at the evolution of luxury fashion’s real-estate presence in Paris over the past 25 years and you’ll see how fashion ‘owns’ significantly more than ever before. There’s the Foundation Louis Vuitton; the Pinault Collection at the Bourse de Commerce; on a smaller scale, Colette is now a large Saint Laurent store; and Le Castiglione is becoming a Gucci megastore. There are entire luxury-fashion retail neighbourhoods that didn’t exist 20 years ago. Has Paris become a fashion playground?

Imran Amed: It’s not so different from what I observe in other cities; this is a global thing. Look at what has happened in Mayfair: Mount Street, Bond Street, Dover Street are all dominated by these luxury brands, hotels and restaurants. We now have entire quarters in cities around the world that are luxury playgrounds. It’s not just the brands, it’s the whole lifestyle: design, art, galleries.

LS: Rather like you have on Omotesando [in Tokyo] or Montenapoleone [in Milan].

IA: You certainly see that happening in Paris, with that incredible Dior store. It is like a symbol of everything that brand stands for, in that historic location where Mr Dior was working, which is now a museum. It is the culture of luxury now. You see the same thing happening even in emerging markets: these dominant luxury brands just cluster together, which in a way is how the customer is shopping, too. It’s of course more exacerbated in Paris because of the scale – Rue Saint-Honoré was always full of luxury brands, but now everything is just bigger. Avenue Montaigne is today on a different scale. The whole eighth arrondissement – everywhere you look is a luxury store.

LS: Luxury brands have become cultural players in that they have redefined the architecture and landmarks of major city centres around the world. These developments have become so large and on such a scale that they have become global attractions in their own right. You now go to Paris to see the Louvre, the Eiffel Tower, the Foundation Vuitton, and the new Dior flagship store.

What is driving Parisian companies and houses’ exponential rate of growth, which is more than, say, their American or Italian counterparts? Is it too easy to say that fashion in Paris has such a rich history?

IA: Ten or 20 years ago, people talked about the fashion capitals interchangeably – London, Paris, Milan, and New York. Over the last few years Paris has become dominant, which I’d put down to the city’s ecosystem, in the same way that Hollywood is where the ecosystem for the US film industry is, or Silicon Valley is where the ecosystem for the technology industry is. You have these clusters that just naturally form and over the last 10 years, and Paris has consolidated its position as the place where the luxury fashion industry is based. An ecosystem is not just the businesses, it’s the talent, the schools, and in fashion’s case, also the métiers d’arts, the artisans who make things. This culture of fashion has seeped into everything in the city, and every designer in the world, whether they are in India, Japan, Belgium or the US, ultimately, wants to show there. They want a presence and a store there. Something has just clicked in the last decade and Paris has become the unrivalled centre.

LS: I totally agree with Imran that the ecosystem in Paris is infinitely better to elsewhere. The root of this lies in a handful of megabrands with a superior business model that they’ve been building for the past 30 or 40 years. If we compare Vuitton, Chanel and Dior to Armani, Versace and Valentino, one of the most important differences that stands out is the ability of the Parisian megabrands to control distribution. Direct distribution – not being in the hands of wholesale – is inherent to their business model, and this has allowed these brands to produce much more effective and more controlled marketing execution, when it comes to controlling your assortment, controlling your shopping environment, controlling your price execution – for example, not discounting. Over time, it convinces consumers that some brands are more valuable than others. Hermès is an investment brand; you won’t find it in end-of-season sales, unlike most American brands and a lot of the Italian brands. Secondly, most of the Parisian megabrands are rooted in accessories rather than apparel, which is a more profitable category. Compare leather goods to apparel and you see better sales-per-square-foot, better full- price sell-through. At the end of the day, you have continuing accumulation of extra resources that you can put to work to reinforce strength and expansion. After 30 or 40 years like that, you build an incredible advantage, in terms of brand appeal and brand recognition, but also, quite simply, financially. The digital revolution of the last 10 to 15 years has only exacerbated this advantage because it has brought more complexity to the industry. It used to be relatively simple: 20 years ago you had to choose a photographer and get photographs published in Vogue; today you need to be on countless social media platforms with different content formats and far more frequent content generation. So you need to spend more money. If you have €20 billion in sales, that can be a rounding error; if you have just €1 billion in sales, that quickly becomes unsustainable.

On the subject of wholesale, the department store was such a significant part of 20th century fashion, certainly in the States, but today’s winning brands completely bypassed that system and reclaimed total ownership of distribution. Who or what is at the origin of that?

IA: It is this old-new phenomenon of taking out the middleman. It is not only the control you have over the entire customer experience, but also the margins that you are able to earn as a result. We have been talking about the direct-to-consumer revolution on BoF recently, but companies like Vuitton, Hermès and Chanel have insisted on that approach for a long time. They were pioneers in the direct-to-consumer revolutions that we now see happening in all parts of the market.

LS: This comes from the Parisian megabrands’ ability to generate high retail-space productivity. When you think about it, being exposed to retail involves a significant amount of fixed costs, like rental costs for prime locations in the most expensive streets in the world, and front-office sales associates who need to be knowledgeable and speak different languages. The difference between making or losing money with your flagship is purely driven by the amount of sales you drive through your square feet. They have relatively compact products with relatively high average price tickets, and scale helps a lot. What lies at the core of our megabrand virtual-cycle concept is that the sales-per-square-foot is driven by the absolute amount of communication dollars you pour into the market. So, as you get bigger and bigger, you can put more and more advertising dollars into the market, while sacrificing a relatively small portion of your top line. In the case of Vuitton today, if you look at 5 percent of their sales, that is €1.1 billion in our calculations, and €1.1 billion is the total sales of many of these small and mid-sized brands that are trying to be revived, like Ferragamo. What is your chance of being seen in this economy of attention when you have a giant dwarfing you and grabbing all of the consumer attention and traffic? Digital has only made the traffic-generation problem more difficult because while consumers have the ability to learn about brands and products online from their KOLs [key opinion leaders], they can also shop online, so there is less interest in coming to the stores. This has forced brands to come to the market with a huge number of new ideas and new initiatives: VIP rooms, temporary exhibitions, pop-up stores, mixing with the art world, and so on. This only increases the bill these brands have to pay, which continues to play into the hands of scale, and continues to increase the megabrands’ advantage. Brands like Vuitton have deliberately driven an escalation in fixed costs because it is in their interest. The more they spend on fixed costs, the more they make it difficult for competitors to keep up and stay in the same premier league.

IA: If you go back to Michael Porter’s ‘Five Forces’ analysis model, which talks about the barriers to entry, over the past decade or so, the ability for smaller players to compete with brands like Vuitton, Hermès and Chanel is now very limited. The barriers to entry have become so high. Not just in terms of the investment, but also because these big groups control all the retail space and relationships with advertisers. They control the whole ecosystem; they have a lock on it. If you are some upstart, you need to be like Jacquemus, a disruptor who comes in with a completely different marketing model based on the virality of the content you are able to create. These viral moments are the only things I can see that can compete with these brands.

LS: I agree. The only successful examples of small players building a niche and carving out a space in the market are those that make the most of being different and can be fast to grab opportunities. If you think about Golden Goose, for example, there was a brief moment during which they could have potentially stepped in and stood out as a specialist in sneakers. Whether that is sustainable in the medium-term is a different debate, but in the short term it allows them to make money and stay in the game.

You have both used the examples of Chanel, Vuitton and Hermès, which all share the idea of tradition and heritage as a fundamental of their communication strategy. It’s this link to Paris and to France that appeals to global consumers. Is the appeal of tradition and heritage here to stay or could new generations of consumers around the world find it less appealing?

IA: I see it slightly differently. Tradition is a fundamental pillar to all those brands, but not their only one; I don’t think it is more important than any of the other pillars such as innovation or culture that they communicate. What is really interesting is when these things collide. Around 2013, I did some video interviews in the beautiful Chanel métiers d’arts ateliers in Paris – like Lesage – what they call the patrimoine of Chanel. We put some of those videos of people making things with their hands onto our social channels – way back before those brands were doing that online – and the response from young people online was incredible. This stuff wasn’t really visible to customers, but the industry has become much more open over the last 10 years. Social media has now enabled the smart brands like Chanel to communicate, beyond the celebrities on red carpets. Have a look at Chanel’s YouTube channel to see the incredible storytelling they’ve done with the Coco Chanel story or about how it creates its products. I don’t think tradition is going away – it’s here to stay – but it is just one of many communication pillars these brands are using to reach different kinds of customers.

LS: The fact these brands have a history allows them to have many different elements in their DNA. Tradition is important, assuming of course you continue to update this tradition, because what we are seeing is how major luxury brands have been very quick to integrate the new relevant values in our society into their marketing narratives. Think about the respect of society and the environment, sustainability — these brands are not just about museum products. They have tradition, they have history, but they are also up to date and relevant in the current zeitgeist. Quite clearly, the brands that got there first occupy the most interesting niche because they relate to mainstream values. Think about Coca-Cola and Pepsi as a comparison to Vuitton and Gucci. Gucci has to be over the top to be relevant, while Vuitton can be mainstream and appeal to a broad audience. That gives them a stronger platform because they are centre stage. In that regard, tradition correlates with the ability to occupy the centre of the market, which makes the brand relevant to a large audience.

To what extent is French dominance of the global luxury fashion industry a factor in the wider backdrop of France, economically and politically? It sometimes feels like luxury fashion is an island of exponential growth within France’s less robust wider economy and its current political instability.

LS: Look back over the past 20 years and luxury and fashion have become so much more important to the French economy. The market cap of the luxury goods sector has significantly increased over that period, which means that a lot of different people can work in this broader ecosystem in one way or another. Luxury is responsible for a significant chunk of the GDP generated in France, as it is in Italy, too. There is an inherent potential conflict when it comes to this industry and broader society, though, because luxury has been thriving by driving income and wealth and inequality. When new markets plugged into the global economy, average GDP per capita increased, but the wealth gap also increased. China and Russia today have very spiky differences between the haves and have nots. As a consequence, luxury has been serving richer and richer consumers, and to some extent is parting ways with the destiny of some of the more mature European economies. Growth has been very hard to come by in the bulk of Europe – particularly in France and Italy – and as a consequence there is a divide between those in this industry and those who are not. What we saw on Avenue Montaigne with the storming of LVMH’s HQ4 is just a sharp example of this.

IA: LVMH also has the highest market capitalisation of any company in Europe now, right?5 That’s another metric. I would underscore Luca’s point around inequality because I think it’s one of the biggest risks the luxury industry faces now. The videos from Avenue Montaigne had a kind of French Revolution feel to them. Whether you are living in London, Bombay or New York, the level of inequality is visible in the streets, and luxury brands and logos might become an emblem of that extreme wealth. I suspect that the next ten years will see more of what we are seeing on the streets of Paris and London. This is just the beginning.

Will that have an effect on luxury’s lustre, its appeal, as the next decade progresses? Or is luxury, with its own eco- system, simply too resilient and robust?

IA: I would take you back to 2008 and Lehman Brothers triggering the financial crisis that affected the world. That was around when Phoebe Philo was starting her tenure at Céline, and there was this whole thing about ‘discreet’ luxury. Now over the last couple of months, what we have all been talking and hearing about is ‘quiet’ luxury. People have become a bit more conscious of the labels and logos and symbols, and so the industry adapts, and starts becoming a little quieter again. We have had an avalanche of really ostentatious, visible luxury these last few years, so maybe this is the trigger for a shift in creative direction that will see more brands like Loro Piana, Zegna and Brunello Cucinelli – the ones riding this early wave – performing well. I think we’ll see that kind of quieter luxury aesthetic move to other brands that have been much louder recently, like Gucci or Versace.

LS: These companies feel this issue, and feel a responsibility to society. Go back to the full-year 2022 LVMH conference and Monsieur Arnault started off by enumerating the contributions that LVMH has made to French society – new jobs added, tax paid over the years, and so on. There is an onus on that, trying to encourage those who have lots of money, and a significantly better living standard than others, to show responsibility to care for the rest of society. When we look at the political implications of this divide, the fine line is when consumers and people at the bottom of the social pyramid stop seeing those at the top as examples to emulate, and instead see them as usurpers and people who got there without merit. That could be a starting point for revolutions. And if, for example, Chinese policy went towards a more populist agenda, then this would clearly be a problem for the global luxury industry. Let me be clear, we have no sign of that at the moment, but I do see a political risk in this inequality situation.

Louis Vuitton surpassed €20 billion in revenue for the first time in 2022 and Hermès this morning posted 22 percent growth for the first quarter of 2023. Despite the turbulent times, there is a sense that some of the bigger houses are now simply too big to fail. Can you envisage in the coming decades Vuitton doubling its annual revenue to €40 billion? Is there a saturation point?

IA: I recently had a conversation with an LVMH executive who disclosed to me that they’d had questions about how big Vuitton could become. In their heart of hearts, they didn’t know it could become a €20 billion revenue brand – but it has. The momentum the brand has shown has given them the confidence that it can grow further. All of that has to be considered against the backdrop of what is happening in the wider economy. We have just been in this unprecedented period of economic growth and then a once-in-a-lifetime pandemic that left lots of money in people’s bank accounts, further propelled by stimulus from various governments. I’m interested to hear what Luca thinks about what the next five years are going to look like.

LS: There are two or three elements we need to factor in. First, the pandemic played a huge role in boosting consumer demand over the past two years. It forced people to save money, and so rich people making significant amounts of money accumulated a huge amount of liquidity. More importantly, it reminded us that life is not forever, and nobody wants to be the richest person in the graveyard. There has been a race to enjoy life, to catch up with time ‘wasted’ in lockdown, and to enjoy the best things in life – including shopping in luxury goods. The theory was that people would swing from spending on products to spending on experiences, but that was clearly wrong. People are in fact spending on everything. This has continued to be especially true at the high end. Look at the statistics: the bulk of growth is being driven by the top decile of consumer spenders. A few days ago, we published data from Global Blue, which can break down their customers by decile, and what you see is that customers in the top decile have increased their spend by 2.6 times between 2019 and 2022. As you move down the deciles, it gets to 2.3 times, 2.1, 1.8, 1.5, to the bottom of the pyramid and the bottom decile, which has increased spend by 60 percent. My assumption is that over time, this post-pandemic euphoria is going to dissipate, people are going to sober up, but the lucky situation for luxury is that the top nationalities are not in sync. We’ve been calling it the ‘growth relay,’ because as American consumers start to moderate their spend growth we have the Chinese consumers stepping in and much faster and to a higher level than most industry insiders anticipated. It is exploding into a spending frenzy that will support the industry for at least another two years. Looking at the fundamental shifts in our society, what we see is the promise that this industry brings to consumers: being better, more attractive, and perceived as more intelligent and more appealing, and the promise of exclusivity. That goes hand-in-hand with a huge rise in people being focused on themselves, which is an effect of social media. On Instagram everyone wants to be a star and stand out. That aspiration to be seen from the best angle has clearly fuelled an appetite for luxury brands, which are conduits to achieving that status. It is not surprising then that megabrands have seen so many new consumers coming to them, and that consumers are trying to find inventive ways to finance their appetites for luxury products. The brands have been smart in branching out into relatively low price-point categories so they can guarantee an entry point to aspirational consumers. Think about all these brands such as Gucci, Louis Vuitton, and Hermès, entering beauty, for example, or eyewear, or multiplying their offer in footwear and sneakers. These are all product categories that allow aspirational consumers an entry point because, while in relative terms to non-luxury products they are expensive, in absolute terms they are not particularly demanding, and a lot of people can afford them. What we need to see is how this exuberant demand will react to a sharp recession and correction in the stock market. So far, the macroeconomic environment has remained benign, with low levels of unemployment and high job security, so the stock market, despite a significant decline last year, is broadly on an even keel. This could potentially be a question mark in the next five years: if we have a real recession then clearly we will not see LVMH and Hermès reporting 18 or 25 percent growth. To the last point you made about how big these brands can become, a couple of years ago, I wrote a report called Selling Exclusivity by the Million, where I went through ten different tools that smart megabrands are using today to get away with murder to sell more and more, while continuing to be perceived as exclusive. Controlling distribution and pricing, and making some of their iconic products very difficult to get, are all conducive to consumers continuing to see these brands as exclusive, even when they sell a lot. People believe Rolex is exclusive and appealing, when in fact they sell more than a million watches a year; Vuitton is selling several million handbags every year. It’s a remarkable feat of marketing that certain megabrands have been able to pull off. This won’t necessarily change going forward because they’ve perfected their methods.

IA: Look at the Vuitton we see in advertising campaigns, social media and at fashion shows, and then at the Vuitton we see sold in the stores: something like 90 percent of Vuitton’s business is made up of products that are part of a growing but relatively stable set of mainstays: classic shapes and silhouettes and materials that are sometimes iterated and specialised with collaborations, like with [Yayoi] Kusama. These are the same designs being made over and over again in quantities that are in the millions. When you have that kind of stable business and you have a product like a Birkin or a Kelly bag or a Cartier Tank watch with timeless appeal, that makes you, to use your words, too big to fail. There are a lot of fashion businesses out there looking for that Chanel bicoloured patent shoe or 2.55 bag that doesn’t date or go away, but most don’t have it. The ones that do, which are those we’ve been talking about, are pretty set.

LS: I totally agree. These brands have very deep and very broad roots. It’s difficult to dislodge them. Brands with less of a set of connections – those with no iconic products or specific values in their history – probably stand a higher chance of falling into oblivion. What I think we are seeing from experience is that even if you run these brands badly — think of Gucci and its near-death experiences in its past history – the moment you dedicate care and attention to them, they come back big time because they are relevant to consumers. So some of the brands are far more appealing as the foundation for a successful luxury goods group. A lot of the success we are seeing today is a function of the industry’s early entrepreneurs securing the best assets. Richemont, for example, is all about Cartier; LVMH – which of course is a very large and complex business – is all about Vuitton and Dior; and Kering is all about Gucci. These brands are indeed, in my mind, too big to fail. Not to mention Chanel and Hermès, which stand out in their own right.

Is there a moment when the groups could become too dependent on the success of one particular house in order to support the rest?

IA: On the contrary, I think that Vuitton generates about half of LVMH’s total profits, and it is exactly having a mainstay brand – a Cartier, a Gucci, a Vuitton – in the group that allows them to invest in other brands. Luca just mentioned Dior as one of LVMH’s megabrands, but five years ago it wasn’t a megabrand. They have invest- ed in that brand for years and years, and then something in the last few years just clicked. To have that patience, and to invest that much money over such a long period and wait, is key. The thing about people like Monsieur Arnault is that they are patient, and part of what allows them to be patient are money-spinning machines like Vuitton.

LS: Indeed, these megabrands almost have a licence to print money. To have such a money-printing machine at the core of the group gives you the ability to invest, be patient, and try to get stuff to stick. Then at some point, it does stick, like in the case of Dior, and recently, Celine. Bringing in Hedi Slimane was a high-profile bet, but in the grand scheme of things, if it had gone wrong it would have just been a rounding error for LVMH. That is because the free cash flow that Vuitton generates is gigantic. Every year it is in the billions of euros, and that covers a lot of mistakes.

Looking at LVMH’s broader stable of brands over the past decade, you can crudely define it as having 50 percent big hitters and 50 percent that don’t seem to be working, and haven’t worked for quite a while. Brands like Kenzo, Berluti, Moynat and others which have never had that same level of performance. How concerning is this for the group?

IA: In the last 10 years, Loewe, Celine and Lora Piana have become billion dollar brands. Meanwhile, others are looking for the right match. What people like Monsieur Arnault and Mr Rupert [at Richemont] and Monsieur Pinault [at Kering] did early on was snap up all the assets and hold onto them. You know, Kenzo not working for a few years doesn’t really matter in the grand scheme of things. A super-high potential, couture-level LVMH brand that everyone is looking at right now, Givenchy, with its incredible DNA and story, has just been waiting for the right match. When they find the right match between the brand DNA, the designer, the business strategy, and what’s happening in the zeitgeist – as happened for Céline and Phoebe Philo in 2008-2009 – one of those brands can become a billion dollar brand. In the meantime they are just part of the portfolio so no one else can have them.

Do you think that keeps Monsieur Arnault awake at night?

IA: What keeps Mr Arnault awake at night is Vuitton and Dior because they are the engines of his business.

LS: LVMH has instituted an interesting organisational framework in which the brands get a lot of latitude, because it would be impossible for senior management to stay on top of what all the brands were doing. The heads of the smaller brands get a lot of latitude and a lot of rope, and if they succeed, fine, and if not, they get replaced. At the end of the day, the amount of damage that they can generate is very small indeed.

About 20 years ago, PPR [the group now called Kering] hired a senior executive from the frozen-foods sector. At the time I remember it raising some eyebrows in the industry. Fast forward to now and it seems that the luxury fashion groups are mature enough that they’ve successfully created a self-recruiting ecosystem. So someone like Cédric Charbit, who started his career as a junior working at the PPR-owned department store Printemps, could then become a successful buyer, and then rise through the ranks to now be CEO of Balenciaga. What are the pros and cons of operating like that and hiring from within, set against hiring people from different sectors who could perhaps be interesting disruptors?

IA: You were referring to Robert Polet, who was CEO of PPR. He brought in the idea of freedom within a framework, which he brought in from Unilever. The talent point is a really interesting one and gets overlooked; it is not analysed as much as it deserves to be. One of the best things these groups have done is cultivate talent pipelines and opportunities so high-potential talents can have mobility within the group. The bigger your group is, the more brands you have in your portfolio, the more opportunities you have to help people develop specific sets of skills that you need to be a successful executive in the luxury fashion industry. The industry might have once joked about the people who’ve come over from the consumer packaged goods industries, but they come with a certain understanding of brand, operating on a global level, and supply chains. What’s often missing though is a certain understanding of the luxury industry, that certain je ne sais quoi that you can only understand once you’ve been brought through the system. The talent pipelines in some of these groups have been a big part of their success, like, as you mentioned, Cédric Charbit, who went from Printemps to Saint Laurent to Balenciaga. There are a lot of people at Kering, like him, who have come up through the Saint Laurent merchandising role to become CEOs or senior executives at other brands. You have these special talent incubators where if you can continue to provide those talents with opportunities, they will stay with you as opposed to being poached to go to another group. You are creating opportunities where they want to move up, if you can give those opportunities within the group, then that is another barrier to entry for competitors, which is another reason these groups become so dominant: they also have a lock on the talent.

LS: Conglomerates have a huge advantage when it comes to recruiting, promoting and keeping the best talent. Another example is Pietro Beccari, who moved from being head of Fendi to Dior and now Vuitton. When you have a good executive, you give them more and more responsibility, which reduces the risk of going wrong and increases the ability to produce strong performance. These businesses are incredibly complex so if you can reduce the mis- takes you make running them, you’re in a very strong position.

IA: Pietro did actually come from the consumer package goods world; he joined Vuitton in marketing.

LS: He did. The luxury industry is still young but getting strong people from FMCG [fast-moving consumer goods] has been a winning strategy at LVMH. Pietro is a great example. I think someone like [LVMH group managing director Antonio ‘Toni’] Belloni has produced quite a significant amount of value. He’s now been at the group for more than 20 years, and before joining LVMH was a senior executive at Procter & Gamble. Or Chris de Lapuente, now running Sephora and the selective-retail division, he also comes from Procter & Gamble. You have companies in FMCG that have been schools of management for a very long time, and a lot of problems within LVMH need a rational mindset and require experience of complex global businesses, like dealing with supply chains, assortment decisions or information systems, and so on. The best companies have been able to combine promoting and retaining talent within the group to being open in terms of recruiting the best possible people from outside industries and getting them to appreciate the specificities and idiosyncrasies of this very different business. They needed to do that because the luxury goods industry literally didn’t exist in its modern format 40 years ago, so you had to build a new generation of managers able to run these businesses one way or another. Those who have decided, by contrast, to work in an imperial way, driving decision-making from the top with the notion that founders and entrepreneurs would never be wrong, have incurred a huge number of mistakes by comparison. Think about Prada and how Bertelli was forced to change his approach; he has recently recruited quite a significant number of senior executives whereas in the past he was concentrating all key decisions on himself.

That leads to my next question. Beyond the dominance of LVMH and Kering, do you sense that other company owners have a clear understanding of where to take their businesses, specifically their heritage brands? For example, Diego Della Valle [of Tod’s] with Schiaparelli, or Mr Rupert at Richemont with Alaïa. Is it a genius strategy that could lead to their potential growth or more a question of alchemy, of creative sparks flying?

IA: With the two examples you cited, it just so happens that the creative talents in those businesses have really put them back in the fashion conversation. I mean, Alaïa was always part of the fashion conversation even if he was happy operating on his own. So, the real challenge was could you find a credible successor who could be respectful of Mr Alaïa’s approach while also trying to bring the brand into the current day and age? And what Pieter Mulier has done is pretty remarkable. With Schiaparelli, that’s Mr Della Valle’s personal investment, it is not part of Tod’s. He is an industry executive who has a deeply held passion and understanding for something as special as Schiaparelli, but to find the talent like Daniel Roseberry who could actually take it and turn it into something that now seems to be working from a creative standpoint and increasingly from a business standpoint is exciting to see. All that said, even with the heft of major billionaire types, those brands still face all the challenges of competing with Vuitton, Dior, Gucci, Chanel on all the different levels we’ve just talked about. So it is going to be a long time before you see those brands achieving anything like the success that you see from the brands within the more domi- nant groups.

You mentioned Tod’s, and Luca, you mentioned Mr Bertelli at Prada. I sup- pose what links those two is the failure of an Italian luxury group to match in any way the success of its French counterparts. With the infrastructure, factories, the allure of Milan and Italian fashion, leather goods, the history of ready-to-wear, all those dynamics, why do you think it has never happened? Is it simply because Italian luxury brands are family-run?

IA: It’s a perennial question.

LS: When you look at what happened in Italy, at least from my perspective, it is like Hermès on steroids. You saw what happened when LVMH tried to take over Hermès, the family reacted very strongly and fought for independence. Look at the Italian fashion and luxury industry 20 or 30 years ago: none of the entrepreneurs of that time was prepared to surrender and sell out to others, or even partner with others. I think there was, on the table, at one point, a potential merger of Armani and Gucci, which was called off at the 11th hour on the back of Armani having second thoughts and not wanting to give up his independence or renounce his role as king of the castle. With many Italian castles and many Italian kings, there was never one king powerful enough to get them all together and to merge into an Italian conglomerate. The difficulty today, if one was to build a fantasy Italian conglomerate, is to find the cornerstone of it, a megabrand that would be able to generate enough cash, as we were discussing before, like Cartier, Vuitton and Gucci generate for their respective parent companies. There is simply nothing in sight, as far as I can see. It is quite an academic exercise talking about the potential of an Italian conglomerate.

IA: The closest thing out there, albeit on a much smaller scale, is what Renzo Rosso has been building with OTB [Only The Brave]. I think he has some beautiful brands – John Galliano for Maison Margiela, Francesco Risso at Marni, Lucie and Luke Meier at Jil Sander, and Glenn Martens at Diesel. I guess Diesel is the biggest brand by far in that group; once upon a time it did a billion euros in revenues. But that is nowhere near where it needs to be. As for Prada, Mr Bertelli tried with a number of brands – Helmut Lang and Jil Sander – and I guess they still have Church’s. So, yes, I am with Luca; I just don’t see it happening.

Let’s turn our attention to Hermès. In an era which arguably is defined by attention-grabbing marketing, logo fashion, and merch-heavy product strategies, Hermès maintains the highest brand equity in the sector, and the company’s stock rose almost 25 percent in Q1 2023. Why?

LS: Hermès clearly has very high desirability and that is a very important asset that the brand can leverage. It also sits at the top end of the pricing pecking order and some of its products have become so difficult to buy that they have become icons and quintessential products. That helps to drive volumes of other products, partly because you want to be associated with such a powerful brand so you buy a lot of trinkets that have relatively inexpensive costs and prices. You can feel you are part of the brand and this very high-end world by spending just a few hundred pounds on a scarf or a belt. Also, if you want to qualify and be allowed to buy a bag at some point, you have to go through the ordeal of buying a lot of other stuff to even be considered. There is the scarcity element that is most relevant and is similar to the scarcity effect at Patek Philippe, where buying the iconic prod- uct has become increasingly difficult.

Would you say Hermès remaining very much a family business means their commitment to maintaining its legacy eclipses the desire for expansion into a group akin to LVMH or Kering?

LS: Yes, I think that this correct; I still see it primarily as a mono-brand business. They have a few other brands already – they have John Lobb and Puiforcat in their portfolio – but these are again rounding errors at best. They have an interest in focusing on what they do and maintaining strict independence, and I don’t see them at any time mov- ing into a different set-up.

IA: I would put Chanel in the same category. Those brands are managed as family businesses in the long term and the only acquisitions you really see or hear about Chanel and Hermès making are in their supply chains. They are acquiring and securing access to the important luxury materials – skins and supplies – that make their products possible. I don’t foresee Chanel or Hermès ever trying to become groups as long as they remain family businesses.

Could the ongoing success of Hermès have a domino effect on the way luxury fashion houses operate in the future, with more emphasis on the house, less reliance on creative directors as marquee names, more constant product range, and less of a desire to become a group?

IA: I actually think the creative strategy is a function of the business strategy and I think that is true almost throughout the industry. If you talk to a lot of people who have been in fashion for 20 or 30 years now, they say the business strategy has taken over the industry, which has professionalised, industrialised, and globalised. The business strategy is a starting point; it just so happens that the Hermès business strategy – putting the house first with less reliance on creative directors and more consistent product range and less focus on trends – is how their creative strategy manifests. At Dior and Vuitton, the creative directors are very much out front, but because there are multiple creative directors, the house is always bigger than the designer. So, Dior is always going to be bigger than Maria Grazia Chiuri or Kim Jones. Vuitton is bigger than Virgil was, and it is bigger than Ghesquière and bigger than Pharrell. But the creative director as hero remains a strategy employed by many brands – Gucci, Bottega Veneta, Valentino and others – that are still putting these stars out front. Gucci had a relatively quiet period with Frida Giannini, who was perhaps not a larger-than-life personality as a creative director, before they plucked Alessandro Michele from behind-the-scenes at the house. He was out front and visible, and his aesthetic was so unique that it became converged with Gucci, and that’s what made the Gucci growth spurt happen. It will be interesting to see what they do with this €10 billion business and what they do when Sabato De Sarno starts. To what extent will Gucci be bigger and more out front than he is? At other brands where they are still scaling up, the designer is still quite important. What Matthieu Blazy is doing at Bottega and what Jonathan Anderson is doing at Loewe makes them really part of what propels those brands, because there is a different business strategy being employed around growth. Sometimes to really drive growth you need a person or a personality who you can connect with a brand. Especially when a brand is in the early stages of entering the public consciousness.

Where do Kering and LVMH go to find growth in new categories? Could you envisage LVMH or Kering acquiring a company like, say, Rolls-Royce? Or perhaps Gagosian, and by extension the estates of leading artists? Or other ‘experiential’ sectors akin to LVMH’s acquisition of Belmond? Or maybe even a Hollywood movie studio or production company to double-down on fashion’s proximity to celebrity?

LS: Two of the most recent initiatives at LVMH – the one in luggage with Rimowa and the one in high-end hotels with Belmond – reveal an interest in potentially exploring adjacent product categories and services, provided that the markets are somewhat fragmented and there is no other obvious incumbent. There should be some potential synergies with what they have already been doing. High-end hotels, for example, are a good way, in my view, to maintain a longstanding relationship with very rich consumers who could potentially get tired of buying personal luxury goods before they get tired of travelling to the nicest hotels in the world. By having them onboard, you can potentially find good ways to reignite a dialogue with them for your core brands, by subtly placing their products or potentially finding ways to talk about them appropriately while they are a captive audience in your hotel. There is definitely an interest in this space. Both LVMH and Kering have recently in- housed their licensees in eyewear, and this dovetails with the interest in more tightly controlling distribution: choosing exactly which stores the products will go to, tighter control of pricing, and also a more cohesive and consistent way of managing communication budgets. So, on the margin, I think that it does make sense. Furniture and lighting are also quite fragmented, and we’ve seen brands like Fendi make good inroads into them. At the end of the day, they relate to a similar desire to stand out and to surround yourself with beauty and beautiful products.

IA: By necessity, category expansion is something these companies will consider for a few reasons. There are only so many of these really special brands that have all that built-in DNA and storytelling material available. When you don’t have many more options of acquiring more brands, you start with the customer. How do you increase that customer’s spend across everything that you do under a certain brand? You lift the overall perception of a brand by operating in those new categories, and the customer then thinks it is a richer brand universe and may engage with you more.

What about brands or groups acquiring, investing more heavily in, or properly developing tech?

IA: Luxury fashion brands are really aware of what their core competency is when it comes to the work they do and the businesses they are building. While tech can be an incredible enabler for luxury brands to engage with customers in a variety of ways, I haven’t yet seen much proof that they can bring and develop and create propriety technology internally that actually leads to successful outcomes. One pretty obvious example is when Richemont first acquired Net-a-Porter, and then subsequently acquired the YOOX Net-a-Por- ter group. Both times, they found that the technology management of that aspect was not something they were very good at. And in fact, they have ended up destroying value there.

LS: When you move into technology, you need to be in a position to do it better than the incumbents. To be fair, this is definitely not the case when we think about products; Apple, for example, is in a much better position – an incomparably better position – to bring value into this space by providing differentiated products in terms of what they do and how they work. Not even companies that have, one could argue, specialised in high-end tech like Bang & Olufsen, are in a position to stay in this championship, let alone luxury brands that come from a totally different background and have no experience either in terms of products or spec services. It requires a different mindset, a different competitive advantage, different people and cultures.

Will that particular case act as something of a cautionary tale for fashion about going into a culture and expertise that is simply too far removed from its core competences?

LS: Yes, I think so. And it is important to take into account what works and what doesn’t in technology, because if you have a strong brand, you are able to generate traffic through your physical stores and also through your brand dot-com, so basically moving into multibrand digital luxury distribution is just not a good idea, no matter how you look at it or who does it. At least, it could be a good idea eventually, after you have lost a ton of money, which is not necessarily what you set out to do as a luxury-goods player.

The luxury groups operate a top-line strategy of merger and acquisition as opposed to research and development. Imran, given that you mentioned earlier this idea of there not being a limitless well of high-potential heritage brands, could you see a point where it would make more market sense for the groups to start developing entirely new brands from scratch?

IA: They have tried, and they have failed. They are not really good at it. This is not an exception in the fashion industry; if you look at most large global companies that generate billions of dollars in revenue, they tend not to be good at creating and innovating from within, which is why they tend to stick with an M&A strategy. If you think about Altuzarra at Kering or Nicholas Kirkwood at LVMH, Christopher Kane, John Galliano, Christian Lacroix – all of these were efforts in one way or another for a major group to try and take something really small and turn it into something big. But it is just not in their DNA to do that. It’s also a structural thing, just how big companies work. The management theory behind this is like Geoffrey Moore’s book Crossing the Chasm9. Typically, it is very hard for big companies to embrace disruptors or new ideas, because they are so invested in their existing businesses that whatever new ideas they may have – and they may be good ideas – they just never focus enough attention or resources to make them a success.

LS: It is not necessarily easier to run a small brand than it is a big brand. I think the point Imran is making is absolutely correct. There is no incentive for executives to focus and concentrate their efforts on small brands, unless they are at the very early stage of their career, and are brought into the group with that, and then promised higher responsibilities as they succeed. For start-ups and entirely new businesses, they probably set up different vehicles for that. Something like private equity or angel investors and keep them out of the LVMH group because it would give them the opportunity to recruit the right people and to have the right incentives in place including equity participation and so on.

IA: The one exception is Jonathan Anderson. When LVMH did that deal for him to take over Loewe, they also made significant investment in his own business, JW Anderson. Because they saw him as a prolific and high-potential creative talent in the group, who has managed to change the fortunes of Loewe, one way to keep him engaged was to put this stake into his own business. And he is one of those rare designers who can oversee multiple brands in a way that is successful and differentiated. On the rare occasion when there is a really high-potential creative talent, these groups will make an investment with a view that the person will take on a creative role in one of their bigger brands, either immediately or down the road. It is a way of solidifying the relationship. Recently we saw LVMH making an investment in Phoebe Philo’s namesake brand, which is coming in September, but again I think that is more about solidifying the relationship.

Turn now to the idea of new markets, certainly the markets we have seen evolving in real time over the last decade. How would you summarise China’s evolution in the luxury fashion marketplace over the last decade?

LS: Clearly, China has been the most prominent new market added to the global luxury goods industry, make no mistake. There has been a series of moments, if we go back 50 years, when the modern luxury goods industry was reinvented from the ashes, thanks to a long list of new markets moving into luxury. Initially Japan, then the Middle Eastern countries, then Russia and then in the past 20 years or so it has all been about China, with even more Southeast Asian markets in the background being added to the long list of countries where luxury goods brands operate. It is not surprising, because my sense is that the fundamental promise that luxury brands offer consumers is standing out from the crowd and being their best selves by owning and buying these products and brands. This desire to stand out is nowhere stronger than in the markets where you had enforced equality. In communist China, where everyone was dressed the same and riding the same bicycle and then all of a sudden, differences were permitted and consumers flocked to luxury brands as if there were no tomorrow. That aspiration to stand out and be different and better will continue to be strong as long as the overall international trade situation allows it.

Imran, what broader impact has this had on the global luxury fashion industry?

IA: The most obvious business impact has been incredible growth and momentum in the market. When you open a new market like that with such huge demographics and undergoing structural economic change that enables it to flourish as the Chinese economy has, it creates a massive opportunity. The Chinese are playing a similar role to the role the Japanese and the Americans did at different points in the past. What is really interesting is the speed at which that discernment around fashion and luxury happened in China, the level of sophistication and taste that Chinese customers have in terms of understanding the brands, and the care with which they engage with those brands. The other really interesting business impact has been diversification, and we are seeing that right now. We were talking earlier about how just a few months ago luxury executives were pretty downbeat about 2023 in terms of maintaining the rapid double-digit growth that we have seen in the industry over the last few years. Then, lo and behold, Xi Jinping in China announces at very short notice that they are doing away with their zero-Covid strategy and three months, four months into 2023, the Chinese market is booming.

LS: Chinese consumers’ significant contribution to the global luxury goods industry also means that luxury goods brands really need to be much more capable of running global organisations. There are countless ways that you can make your business and global messages, even your products, relevant locally, but that demands you recruit the highest level of local talent, and create organisations that are more sophisticated than just working from centralised quotas in Paris and Milan and leaving all the key decisions to French or Italian executives. The significant importance of China, with its very specific culture and social circumstances, has required that large luxury goods companies integrate Chinese talent in virtually all of the steps of the value chain.

You’ve both mentioned how quickly the Chinese have acquired both the business culture and a discernment around luxury goods in China. With this in mind, could you envisage a globally successful luxury fashion brand emerging from China; one that is no longer reliant on the cultural traditions of Europe?

IA: Yes, it is such an interesting point and important question, because one of the frustrations that so many customers in Asia have is that they are only seen as consumers of luxury. I use the word ‘consumer’ intentionally there – I typically don’t like to use that word – because if luxury brands in the West only see Chinese customers, or customers from other parts of Asia, as consumers then they’re missing an opportunity because there is creativity in those countries, as there is everywhere in the world. One of the most recent developments that we have been observing in the Chinese market is the growth of home-grown brands. Are any of those brands on the scale yet of the major European brands? No. But is there interest from Chinese customers in buying Chinese brands? Yes, absolutely there is. One of the interesting ways that that has started to happen is a lot of young creative Chinese people have studied in fashion schools in the West – at Central Saint Martins, Antwerp or Parsons – and then returned to China to set up what you might call hybrid businesses where they do a lot of the operational manufacturing and back office work in China but have strong relationships in the West where they show their collections. It is a Chinese run and Chinese-owned business that is connected to the West. Hermès actually tried to build a native luxury brand called Shang Xia, which didn’t work out for them. You do see the emergence of these Chinese-led businesses and we should one day see a major brand come out of China.

LS: Yes, and we already have a number of brands standing out from the crowd, think of Icicle, for example, which holds promise. I see hundreds of them actually. There is going to be a very high mortality rate though, and only a handful of them will come to prominence. I think this is going to happen sooner in the accessible luxury market than in the high end but I think we should be prepared to find examples at all price points.

This next question is as philosophical as it is related to culture or education, but could you envisage Made in China one day gaining the same status as Made in Italy?

LS: The Japanese were once seen as copycat players and now Made in Japan stands for the highest technology and quality level. So why not? In a number of product categories, China has already reached high and sophisticated quality levels, take eyewear, for example, so I don’t think there is anything particularly standing in the way of Chinese workers acquiring some of the most sophisticated competencies. There are clear learning curves for them to embrace and go through. China has been upgrading the quality of its products for a while when we look at apparel or leather goods, so I don’t think it’s impossible.

IA: The other thing I would add is that I have observed in different markets, not just in China, but in India and Southeast Asia, how the luxury industry is currently obsessed with craftsmanship and crafts in particular. Often times, what countries in these other parts of the world can offer is a link to their own history with crafts. When you marry that craft with design, you take these age-old techniques and com- bine them with a design sensibility that is marketable and appealing on a global level. That is where there are really interesting opportunities for these countries to be part of the ‘Made in’ phenomenon that you see around the world. If you think about the recent Dior show they did in India, for years, these luxury brands have been silently making embellished and embroidered garments in India, which has a very long history and tradition of passing down this age-old craft for generations. The show that Maria Grazia Chiuri did in India was the reflection of a 20-year relationship that she has had with this one particular atelier of artisans in Bombay, and it was just really powerful to see this Made in India, which doesn’t necessarily have the same cachet as Made in Italy or Made in France. But Made in India, Made in China, Made in Vietnam – all these countries have traditional crafts and skills they can offer to the luxury market globally.

A fashion critic told me that Miuccia Prada is genuinely curious about understanding the distinction between making something she thinks is great but that doesn’t sell versus making something more pedestrian that makes her company a fortune. She says, ‘I make a black dress and a pink dress, why does Prada sell 10 times more the black dress? I make a brown coat and a leopard-print coat, how come Miu Miu makes ten times more from the leopard-print coat?’

IA: When you think about the two examples you cited, a black dress and a leopard-print coat, it kind of goes back to what we were talking about earlier. In people’s minds, the thing they want to invest in at a Prada-level price point is a timeless thing: a black dress. I mean, there is a reason why we think of a LBD; for me, part of it comes down to, if you are going to invest two or three thousand dollars in a Prada dress, are you going to get the black one or the pink one? Very few people can get the pink one and justify it. There is that elite customer group that maybe have 70 Birkin bags, but for the average person if they are going to drop that kind of cash, they are going to get the iconic product, which in part is what makes it worthy of the investment.

LS: This is, I think, a very interesting question and the answer is to see that the merchandising director and the creative director are possibly equally important. And this is a point that Kering has embraced very successfully, wanting to get creativity that is both distinctive and commercially viable. We look at the partnership at Gucci between Alessandro Michele and Jacopo Venturini, that has been a very effective duo – both in terms of driving the aesthetics of the time, and in terms of driving financial performance. So, I don’t think the two need to be mutually exclusive, you just need to have an eye on both elements, because this is an industry, not an art. If it was enough to be very creative and produce a piece that goes into a museum, it wouldn’t be a business. In order for it to be a business, the creativity has to be commercially viable. So these two functions, elevated at the same level, probably guarantee that we have better results. I think the old model of having the creative director as an almighty, all-powerful and all-knowing creature in the designer-centric organisations we had in Italy in the late seventies or in the eighties, has long succumbed to the complexity of the market environment. So, you need better set-ups than that.

The representation in the fashion industry of people from broader ethnic, gender, queer, and other communities has evolved over the past decade – arguably, in response to shifts and events felt outside the industry. Where do you see evidence of the positive changes within the industry – in particular at C-suite and boardroom levels – and what have these changes brought about? Where in particular do you see the need for improvement?

IA: I would say that this is historically an industry that has both actively and systemically excluded people who are different from the kind of elite privileged people who originally ran this industry, and who continue to run it. I don’t think that has changed that much, even with the events happening in the world, even with high levels of consciousness about the value that different perspectives can bring to the way a business is run and how it works. This is even more salient if you just think about who the customer base of the luxury fashion industry currently is. It is no longer dominated by people in North America and Western Europe. In fact, as we previously discussed, the biggest, faster-growing markets are all in Asia or the global south, and it is really interesting and slightly counter-intuitive that while your fastest growing markets are in China and the Middle East and India, the boards of most of the companies have absolutely zero representation from those customers. When you are thinking about strategies or having to make decisions about the kind of long-term direction of these companies, if you don’t have those perspectives in the boardroom, how can you make those decisions effectively? Kering has made some progress in its board structures; there are a few female CEOs at Kering and at LVMH, people like Francesca Bellettini at Saint Laurent or Pascale Lepoivre at Loewe, but you can really count the female CEOs on one hand. Probably the most notable appointment in recent years was Leena Nair as global CEO at Chanel, which is a position that had been vacant for quite some time, in fact since another woman, Maureen Chiquet, departed. As a person of colour and someone who comes from India, that is probably the most interesting shift that I have seen, especially for a company like Chanel, which is one of the most elitist exclusive and privileged brands and leadership groups historically. That’s a big and promising change from them. Overall, when I look around the industry, I can say that most of the people don’t look like me. On the creative side, it is almost exactly the same issue, very few female creative directors, and so that is why Virgil’s time at Vuitton was such a lightning bolt for so many people in the industry. Even after his passing, he has become a role model for so many young people who don’t come from these privileged backgrounds and want to see an opportunity for themselves in the industry. So yes, there has been a little bit of change but not nearly enough.

Should LVMH or Kering invest more in philanthropy? Or rather, in the future, would it be naive to think that they’d need to invest more in, say, saving the Amazon forest?

IA: No, it’s not naive, I also don’t think it is a question specific to fashion. All companies are thinking about how and what and why they should give back to the communities they operate in. Some of the sensitivity around the speed with which Kering and LVMH made donations to the Notre-Dame restoration project was that when other things in the world happen, they don’t donate as much money or take action as quickly. I think that is partially because they’re not thinking as broadly about the community that they operate in. As global companies that have supply chains and customer bases around the world, my only reflection is that all global companies need to think and give back globally. That would include things that sit outside where their companies are headquartered, but also where their employees live and work and where their customers live and work. That is where business is heading now, some are calling it stakeholder capitalism; you don’t only think about your shareholders, you think about stakeholders, customers, your employees, and the communities where you operate. It isn’t a naive question; the role these businesses have to play in wider society is even more important now, because they are generating so much wealth and so much profit. And the question is at what point do they need to start giving some of that back?

Finally, Succession has captivated audiences around the world in the last few months, and fashion has its own real-life succession playing out at LVMH. Does the reality of LVMH’s future succession mean the group can sustain its market confidence and growth beyond the lifetime of Bernard Arnault?

LS: He could stay in the job for another five years at least, but for sure the issues of succession will have to be addressed and effectively resolved.

IA: I think the succession feels very secure. The difference between the TV show is that the potential successors here are all ambitious unlike the characters on the TV show. They are more talented and hardworking, and they seem to get along much better with each other. Let’s be honest, Bernard Arnault is a once-in-a-generation entrepreneur who stands alongside legendary business leaders like Steve Jobs and Walt Disney in what he has created. That is his legacy. No single person will replace him. The siblings as a group will succeed him and it won’t be one person who everyone looks at. I think he has left a whole group of people who have been schooled and educated in business from a very young age, and they are all very capable.

LS: My understanding is that this is an issue for all the other companies we have talked about. If we look at LVMH, Kering, Richemont, Swatch group.

What do you think Bernard Arnault’s legacy will be?

LS: Arnault has definitely been able to unlock the opportunity of high-end brands appealing to a very large audience, while maintaining their exclusivity in the eyes of the audience. If I was to squeeze it to the very core, this is the lesson that European luxury has taught American luxury. While American brands or aspiring luxury brands have at some point met with huge commercial success, they were not able to administer and manage this success to maintain the success over time. They went overboard. I remember Michael Kors being distributed on all four corners of the road, and quickly becoming ubiquitous and quickly losing his cachet.

IA: Legacy is very much linked to this idea of giving back as well. If I were in Mr Arnault’s shoes at this stage I would be thinking a lot about that. You know, once you have created so much, what is it that you want to leave behind besides the world’s largest luxury group?

This interview first appeared in System Magazine’s 10th anniversary issue.