After the loss of her closest collaborator, the singer-songwriter paused but didn’t retreat. “The Greater Wings,” the follow-up to her 2017 breakthrough, is due Friday.

“I’m not trying to be eccentric, I promise!” Julie Byrne joked as she carefully arranged colorful tiles and bits of clay on the dining room table of her minimally furnished Queens apartment. The singer-songwriter, cozily stylish in a milk chocolate-colored tank top, cargo pants and snug knit slippers, located a pair of jagged white tiles that bore a phrase scribbled in black Sharpie: “Letting go.”

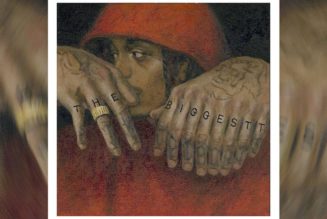

“There was a third one that said ‘future,’ but I gave it to a friend,” Byrne said, explaining that those messages help tell the story of her first record in six years, an incandescent collection of ambient folk titled “The Greater Wings,” due Friday.

Byrne, 32, hadn’t necessarily planned the long gap after her 2017 breakthrough, “Not Even Happiness,” an elegant and emotionally astute album that brought her critical acclaim. But that album’s closing track, “I Live Now as a Singer,” became something of a manifestation. She toured for two years and relocated to Los Angeles from New York in late 2018, and found herself living as a working musician for the first time. It was an uneasy transition.

“It was a period of tremendous absorption in my own doubt,” Byrne said. “It took me a long time to learn to work well on my own time.”

Byrne grew up in Buffalo, N.Y., where she passed time climbing grain mills and exploring the city’s abandoned Central Terminal. She picked up the guitar at 17 and taught herself on an instrument that belonged to her father, a fingerstylist who stopped playing after a diagnosis of primary progressive multiple sclerosis. “My guitar work,” she noted, “is a family inheritance.”

After high school, Byrne spent the next few years floating across the United States. “My mom traveled quite a bit when she was that age, and I fell in love with her stories about that time,” Byrne said. “I had hardly been anywhere and was hungry to experience more. There was a lot of romance in that dream.” She developed her songwriting voice along the way, releasing several cassettes of haunting folk songs, which were later compiled into her 2014 debut, “Rooms With Walls and Windows.”

Three years later, “Not Even Happiness” brought her music to a wider audience, propelled by Byrne’s dedication to nonstop touring. The success, however, generated some stress around her process. “While there is mysticism in creativity, there would be times where I was lost in a mind-set of only wanting the process to be mystical,” she explained, letting loose a bright chuckle before turning pensive again. “When I was younger, I approached writing as something that occurred spontaneously, rather than through perseverance and the raw, honest effort of showing up day in and day out.”

In the winter of 2020, Byrne had recently moved to Chicago from California to be closer to Eric Littman, her longtime creative collaborator. After meeting in 2014 at South by Southwest, where Littman engineered a performance that featured Byrne playing in a dried-up creek bed, the pair were immediately aligned, creatively, and for about a year, romantically. Littman became Byrne’s go-to musical partner while also making his own bedroom pop under the moniker Steve Sobs and leading Phantom Posse, a New York-based collective featuring artists like iLoveMakonnen, Vagabon and Emily Yacina, whose solo music he also produced.

After a first attempt at recording “Not Even Happiness” in Brooklyn, where they struggled to capture a tranquillity amid the chaos, Littman and Byrne relocated to her childhood home in Buffalo for four months. Both were eager to recapture that immersive creative energy for “The Greater Wings.” While Littman worked as a cancer researcher by day, in the evenings and on weekends he and Byrne would tinker away at song drafts that became tracks like “Summer Glass,” a shimmering, synth-driven standout on the new album that ends with the line, “I want to be whole enough to risk again.”

By early 2021, Byrne and Littman were working steadily on songwriting, traveling the country to record harp and string arrangements. But in June of that year, Littman died suddenly at 31. Byrne declined to speak to the circumstances of his death, which remains a profoundly destabilizing loss.

“He was a truly brilliant person, he had so much faith in me and what we had set out to do together — that never wavered,” Byrne said. “It wasn’t even his vision or technical skill or artistry that made the collaboration so rich and singular, it was his love and care.” Work on “The Greater Wings” paused for seven months as Byrne moved back to New York to be closer to her support system; her current apartment is just down the street from the one she and Littman shared around the time they made “Not Even Happiness.”

At the time of Littman’s death, most of the album had been mapped out and at least four songs were near completion. When it came time to reopen the record, Byrne sought outside support. Ghostly, the experimental and electronic record label that later signed Byrne, connected her with Alex Somers, a producer known for his work with Sigur Rós and Julianna Barwick.

“Julie and I had been friends for years and Eric was a big part of my community,” Somers recalled over the phone. A friend at the label gave him a message: “Julie doesn’t want to retreat.”

After several informal hangouts at Somers’s Los Angeles home, Byrne and her collaborators regrouped in January 2022 at a cozy studio in New York’s Catskill Mountains. “It was a really charged experience,” Somers said. “Every single day, at least one person was in tears.”

But as Byrne sings on the serene “Portrait of a Clear Day,” “Love affirms the pain of life.” So while loss loomed over the album’s completion, Byrne emphasized that “a majority of it came from life, our life together, not from death and grief.” She added, “The deep wild romance of friendship is very much at the heart of the record.”

It’s a sentiment clearly articulated on the title track, which Byrne completed after Littman’s death. Atop a meditative guitar melody and celestial ambience, Byrne sketches scenes from her shared past with Littman while committing to continued artistic evolution: “I hope never to arrive here with nothing new to show you, as so many others have.”

“There’s a sense of responsibility in that line, to embody the statement with my actions, not only with my words,” Byrne said. “Perhaps the act of finishing the song itself is one of many beginnings in that effort.”