AML, a groundbreaking social project and digital hub for collating and sharing extensive knowledge about African music, recently launched the Foster Program.

The founders hope to transform the African music landscape through the initiative by revolutionising how the continent’s music is documented, celebrated, and preserved.

In this interview with PREMIUM TIMES, Anu Onasanya, Project Lead for the Foster Programme, explains in detail how the programme is working to preserve the knowledge of African music and much more.

Excerpts.

PT: What is the African Music Library (AML) all about?

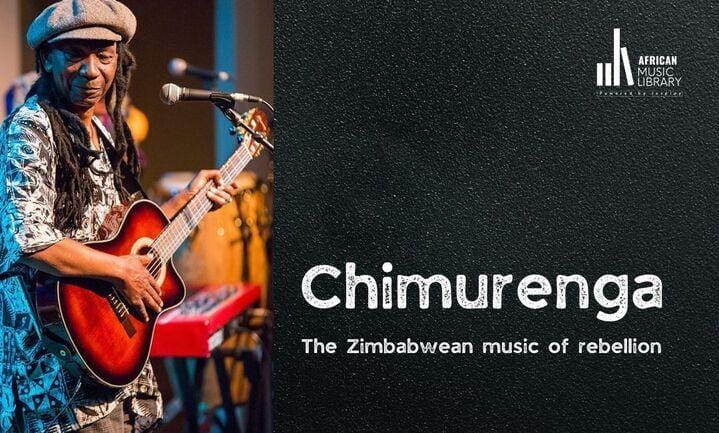

Anu: AML is a social project formed by music enthusiasts and African culture experts passionate about building, collating, compiling and sharing deep knowledge about African music.

So, when people think of African music, they might first say, “Oh, is it not the music that we listen to or what? But African music is much more than that. So the African Music Library encompasses the genres, the African genres, the African instruments, to the African artistes themselves – it contains everything that has to do with African music, including the research. So the African Music Library is like a body of knowledge or a platform for bringing this body of knowledge about African music together.

So, you have musical instruments from pre-colonial to colonial days and postcolonial era that we have researched, working with musicologists, ethnomusicologists, and African music experts and bringing this body of knowledge together on AML. So, AML was officially launched last year, 2022, and we boast almost 12 million data points that we’ve been able to collate on the African Music library.

PT: What solutions are you creating with this data?

Anu: The goal is to document African music metadata – to establish, on record, who did what when it was done, and who were the people that were part of this body of work. In the long run, this would help African artistes get duly rewarded with royalties for what they’ve done or what they do in the future.

It also helps us to solve the problem of misrepresentation of African music. Almost everybody thinks that every music that comes from Africa is Afrobeats. But that’s not true. We have several indigenous African genres, and they exist across the African continent, but when African music is being represented, they say, oh! He’s singing Afrobeats. But it is something more than that. So, AML ensures proper representation of African music on the global stage.

PT: Tell us more about the African music library.

Anu: There are two aspects to this question. AML is an e-library. The world has gradually moved from the physical use of CDs, DVRs, and cassettes in the ’90s. The world has moved from there, so most bodies of knowledge are now saved in soft copies. AML is an e-library where we store all those data points we discussed – almost twelve million (12,000,000). We have over one hundred thousand (100,000) genres, more than eleven thousand (11,000) artistes being represented, and readily available online. You can find any of this information on www.africanmusiclibrary.org.

PT: Why should the average African artiste be interested in AML?

Anu: As an organisation, we have seen over time that in African music, there are different music identifiers (ISNI, ISWEC, UPC, ISRC, etc.) with releases that enable a musician to be paid royalties for their work. Not only artistes now, but I’m also talking about everybody involved in making a song right from the conceptualisation to its release. Besides the artiste who owns the song, different team players unite to make it happen. The writers, producers, sound engineers, publishers, and CMO (Collective Music Organisation) must be rewarded for their efforts.

The African Music Library helps them get rewarded in terms of being able to collate these metadata, ensuring that everybody is adequately represented on the particular song that they were part of the process. When Apple, Spotify and other DSPs want to pay royalties to people involved, everyone involved in the project gets their due royalties for participating. So, the AML helps compile that metadata which most DSPs might not have.

PT: How do you gather this data and ensure all these parties get paid?

Anu: On how we get our data, we don’t just scrape data from the internet because there’s a high chance that you may retrieve the wrong data. We have a well-trained team of quality assurance experts who perform due diligence on the data we collate from different sources – whether it is an artist reaching out to us requesting a profile be created for them. Many are reaching out with requests, whether it is an artiste in Nigeria or abroad. So, whether you are reaching out to us or we are getting the data from other sources, we ensure that we have a team of dedicated experts that provide that every data put out there is correct. It is checked and double-checked to ensure that people are adequately identified for what they do and represented. We have notable organisations like Song Writers Council in South Africa rely on our data and other data to ensure that writers duly pay their royalties.

PT: What inspired the creation of the Foster Programme, and what are the objectives?

Anu: The Foster Programme aims to bring the knowledge of African music to the children, the understanding of it, and ensure that some genres and information about African music continue after this generation. More So, the Foster Programme is trying to ensure that the rich diversity that comes with African music is preserved. So that everybody is not just doing Afrobeats today and then move on to Amapiano, then to Soukous etc., we don’t want that. What we want to achieve is a transfer of the rich diversity of African music to the next generation.

PT: What do you do on a typical Foster outreach day?

Anu: Foster is a three-phased African music education initiative. It is three-phased in that we have the music appreciation first, the music theory second, and the application of what the children learned in the appreciation and theory phases, respectively. Each of these programs lasts for weeks apart. So, on a typical Foster outing day, our first phase starts with appreciation: what does African music sound like across different music, genres and instruments? So, we take that for about six to eight weeks.

The theory aspect now takes them through talking about these instruments, the music and genres.

READ ALSO: MOVIE REVIEW: ‘Obaram’s brilliant musical, cinematographic elements make it a near masterpiece

Depending on your phase or the particular school or community, a typical day can be for appreciation, theory or application. The application phase deals more with the practicals. For instance, we teach the pupils how to beat the Bata drums or the Ogene gong or properly posture properly; what is the dance formation for the average African dance movement? As I said earlier, the phase that a school or community is in determines what a typical outreach day looks like.

PT: Who are your target audience for the Foster Program?

Anu: Since we are still growing, our main audience is typically children – children in primary schools. We do not just all primary schools; we target mainly public and private schools in low-income neighbourhoods. We know their parents cannot afford the luxury music education that the big league or middle-class private schools provide. Note that not just music education but African music education to the children. So, at the moment, we are prioritising public primary schools and private schools in low-income neighbourhoods. This is what we are focusing on right now. In the long run, we are looking at onboarding secondary school students.

PT: Does Foster have plans to collaborate with other organisations to achieve its aims?

Anu: Yes! We intend to collaborate with other organisations to ensure we reach beyond Nigeria or Lagos. We have approval from the Lagos State Universal Basic Education Board (SUBEB) for Akoka Primary School and have started already. We are also negotiating with a privately owned network of schools to see how we can onboard Foster to their schools across Nigeria. We are also considering partnering with music schools and those willing to support us with music tutors. In a hundred or a thousand years from now, African music will not go into extinction but will be passed on from one generation to another. As we speak, there are some African musical instruments that people cannot play anymore because the previous generation did not pass them on.

PT: Some of these schools have children with special needs, and they enjoy African music as well; how does Foster handle inclusivity in its operations?

Anu: For Foster, there is no discrimination in terms of sexes – whether you are a girl or a boy, we usually give everyone equal opportunity. We leave no child behind, whether you are autistic or not. Once we get to a school and discover, for instance, a child with special needs is in the class or group, we usually make special arrangements to accommodate them and make them participate fully.

PT: Are there plans to expand the programme’s reach or introduce new initiatives in the future?

Anu: Yes, we intend to. As I have said, we call on the public to collaborate with us. This is because we plan to expand foster beyond Nigeria to across Africa. We are hoping that in the first five years of the program, we can grow Foster across Africa, and this is why our doors are wide open to collaborations that would make this happen. It takes a lot of resources, funding, experienced personnel, dedication, and capacity to achieve this.

We intend to do this by introducing a scheme we call “Train the Trainer”. We would have different teams working in various locations across the country or continent.

PT: Do you intend to make Foster a continuous program in schools? Will you create curriculums for this program that schools can adopt?

Anu: We currently have a 30 weeks curriculum with the Nigerian education system. So, Foster would be running for 30 weeks spread across a session – three terms. We layered the curriculum with the school curriculum so that there is continuity. It is not just a one-off thing. And we hope that government and state school boards will adopt this curriculum across Nigeria and Africa in the long run.

PT: Does Foster help identify talented and exceptional children?

Anu: Thank you very much for this question. The first is recognition and awards. As I said earlier, we look forward to partnering with music schools. In the long run, once we identify these exceptional children, we give a certificate of completion at the end of the initial circle Foster. Then they get a scholarship to attend a music school after the program based on the music schools we partner with.

PT: Finally, what message do you have for the music community and potential collaborators?

Anu: My message on behalf of the African Music Library regarding Foster is that music education is no more an extended luxury. It has become the fundamental right of every child regardless of background or circumstance. Every child deserves access to music education. Music education can become a lifeline for underprivileged children – offering them opportunities for personal growth, self-expression, and empowerment.

We look forward to everyone joining us to make African music education an opportunity for every child.

To volunteer for the Foster program, please visit our website, www.africanmusiclibrary.org, click the participate link, fill out the registration form, and we will be in touch immediately.

Support PREMIUM TIMES’ journalism of integrity and credibility

Good journalism costs a lot of money. Yet only good journalism can ensure the possibility of a good society, an accountable democracy, and a transparent government.

For continued free access to the best investigative journalism in the country we ask you to consider making a modest support to this noble endeavour.

By contributing to PREMIUM TIMES, you are helping to sustain a journalism of relevance and ensuring it remains free and available to all.

TEXT AD: Call Willie – +2348098788999