Afrobeats rode on its own generated zeitgeist to become a staple of the global cultural marketplace. How does it negotiate a bigger piece of the pie?

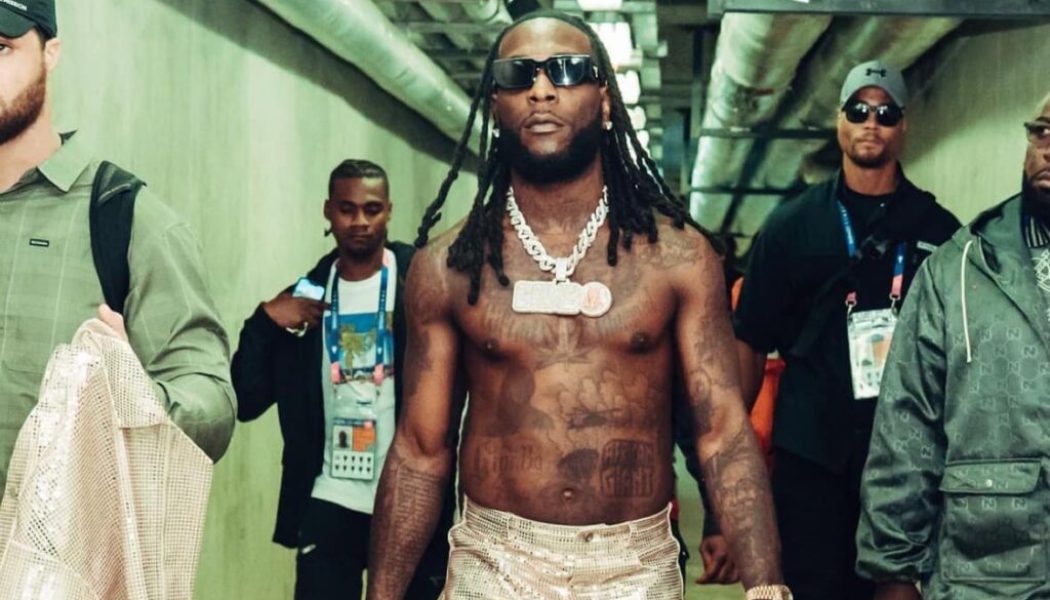

Burna Boy was the main act the 2023 UEFA Champions League final in Istanbul on June 10th.

Afrobeats – not to be confused with Afrobeat – reached unprecedented heights in 2022, with established stars like Burna Boy and Wizkid lodging their names deep in the global music scene, while new-comers like Pheelz were able to break through the noise and carve out a space for themselves in the hyper-competitive music space.

Despite seemingly overnight success for the relatively young music genre, its trek to the peak has been over 70 years in the making, its triumph being the culmination of inter-continental traversal, borrowing from music genres like jazz and rock and roll, musical and personal inspiration from Afrobeat legends like the late Fela Kuti and extremely crucial endorsements from people all across the globe; from British radio hosts who helped introduce Afrobeats to listeners in the United Kingdom to D’Banj and Fuse ODG, arguably the first Afrobeats superstars.

Indeed, Afrobeat forebears laid down the cultural groundwork that Afrobeats artists now enjoy. Afrobeats is an all-encompassing phrase for music that fuses contemporary genres like hip hop,house and RnB with West African rhythms .Similarly,the birth of Afrobeat is linked to sounds from Nigeria and Ghana –highlife,Yoruba music, juju– that Fela Kuti later blended American jazz with. It is this persistent interchange of cultural artefacts among the West and Africa that continues to breed invigorating new music.

To understand why Afrobeats is popular today, it is important to explore the forays taken by African artists over the years and how this paved the way for Afrobeats. The quest for appeal beyond African borders is not unique to Nigeria;African musicians across the continent have all worked to expand their art beyond the confines of their countries. Africa’s musical appeal dates to the 1950’s and early 1960’s with Congolese bands like Franco’s OK Jazz and African Jazz, who integrated new instruments like electric guitars in their music, transforming Congo into Africa’s music hub.

South African born Miriam Makeba was particularly successful in the United States.In 1967, she made history as the first African artist to appear on the U.S Billboard Hot 100, a chart that tracks the most popular songs in the country.Her iconic song “Pata Pata”, peaked at number 12 and stayed on the charts for 8 weeks. She was embraced by American audiences due to her songs as well as her live performances, and was responsible for creating a notion contrary to what Americans knew about Africa. The trumpeter Hugh Masekela was also massively popular. In 1968 he released the chart topping hit “Grazing in the Grass”.

During Fela Kuti’s 10-month tour of the United States, he recorded the album known as The ‘69 Los Angeles Sessions.This turned out to be a watershed moment in the Afrobeat movement. Tejumola Olaniyan’s Arrest the music: Fela and his Rebel Art and Politics describes it as a ” fusion of indigenous Yoruba rhythms and declamatory chants, highlife, jazz, and the funky soul of James Brown”. The album birthed Afrobeat, and was recorded at a time when Fela’s worldview was rapidly radicalising, as he embraced the radicalising: he was looking to Black America for soul, funk and Black nationalist ideology, was embracing the Black Consciousness movement and becoming a leading voice against neo-olonialism and Big Man corruption in Nigeria and Africa. It was this new consciousness that set the stage for his anti-government protests and music.

The drummer Tony Allen was a key figure in fashioning Afrobeat. Here is an excerpt from his biography describing his style.

Tony’s sound is most accurately described as a jazz and funk-inflected rearticulation of rhythms drawn from local Nigerian and West African genres such as highlife, apala, and Nigerian mambo.

This set Fela up for success for the next decades.

Improvements in music technology in the ’80’s saw significant leaps in popular music. African music was not left behind. King Sunny Ade’s juju music’s success in international markets was particularly impressive. Following the decline of highlife from the 1970’s as a result of emerging genres like Afrobeat, Sunny Ade adopted distinct patterns that enabled him to stay afloat. His use of the pedal steel guitar alongside standard Yoruba instrumentation, coupled with his elite showmanship in live settings resulted in the landmark 1982 album Juju music, the first West African album to be heavily promoted in the West. Sunny was the first African artist that music labels attempted to introduce to a global audience, using tactics like collaborations with American artists, touring all over the world and culling from his massive catalogue to create tunes that Western audiences would like.

Just like decades prior, where music genres coalesced to form novel sounds, Afrobeats emerged. Abrantee Boateng, radio host and event promoter who coined the term and championed Afrobeats, said in an interview with The Guardian that Afrobeats is an amalgamation of traditional Nigerian and Ghanaian music – think highlife, juju – but infused with hip hop,EDM and funky house music. It developed from radio shows and music festivals in the UK and coincided with the rise of popular musicians like Wizkid and P-Square. In an article on Billboard magazine, culture writer Christian Adofo said that England’s nightlife scene, particularly among black university students in London, pioneered the sound.

Afrobeats takes the best from both worlds: elements from Afrobeat and from popular American and European music.This heterogeneity has aided its rapid popularity and has given rise to a new breed of superstar artists. Afrobeats lends itself well to the American and European popular music formula, and its best offerings, from Sarkodie’s rapid-fire flow or Tems’ soulful singing isn’t particularly different from anything on the BillBoard Hot 100.

The last decade has consequently served as a homestretch for Afrobeats, with the benefits of global communication opening doors for African artists and music to the West.Proof of global appeal due to songs like Ckay’s “Love Nwantinti”, Rema’s “Calm Down” or Tekno’s “Pana” coupled with Africa’s emergence as a viable music market has once again led to interest from music labels; global marketing firms responsible for finding, nurturing and exploiting musical talent have returned to the continent.

Afrobeats stars are confident of Nigerian music’s takeover. They have taken stock of the changing tides in popular music consumption, and how the world is reacting to music from Africa.

As a result, these artists have gotten recording and tour deals, business partnerships that grant marketing and promotion of an artist’s music in exchange for a percentage of the royalties generated from the music.

Perhaps this desire for acceptance abroad could prove to be a stumbling block. Signing to a label is beneficial for an artist’s career growth, but it may impede new artists and genres as the labels try to align their music with what they think will appeal to European and American audiences. Afrobeats artists thus have to be wary of exploitative deals and educate themselves on the music business.

Burna Boy revealed that he was giving away a huge chunk of the money generated from his biggest song, smash hit “Last Last” to Toni Braxton because he sampled her 2000’s song “Wasn’t Man Enough”.

“She is taking 60 percent”, said Burna in an interview.

Fela Kuti and King Sunny Ade were adamant about signing to music labels. Despite Sunny’s success, his refusal to abide by the West’s pop terms contributed to the termination of his contract with Island Records.

In addition, “the pop-ification” of Afrobeats has led to the loss of a component that made Afrobeat tick- its political consciousness. Afrobeats artists –not unlike American artists– stay conspicuously silent about politics

In conclusion, Africa’s foray into global music visibility can be likened to a relay race. Afrobeats stars are taking the baton from their forerunners and are racing, hurtling to the finish line that is mainstream appeal. The race has been fascinating to watch thus far, and the world is eager to see what happens next.