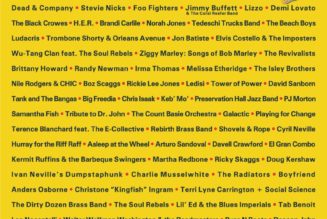

BCUC has to be one of the more unusual bands to emerge from South Africa‘s alternative music scene in recent years. Not amapiano or gqom or hip-hop, and certainly no throwback to Soweto jive, “bubblegum” or its post-apartheid offspring kwaito. No, no, no. You might describe them as Afrofuturistic punk, but really, that starts to feel like throwing words at a sound that defies classification. This seven-piece band presents a frenetic boil of energy on stage, as we discovered recently seeing them perform at the Sauti Za Busara festival in Zanzibar. The sound is a barrage of drums, voices, whistles and booming electric bass. Melodies collide with shouted chants and multi-lingual raps in a dizzying swirl of pent up energy, spirituality, political passion and no-holds joy. You have to experience it to truly get the picture, but you can get a clue from their fourth studio album Millions of Us, out this week from On The Corner Records.

BCUC stands for Bantu Continua Uhuru Consciousness. They rehearse in what their PR describes as a “shipping container-turned-community-restaurant.” (Still trying to picture that one…) In any case, after seeing the band‘s headlining set one late night in Zanzibar, Afropop‘s Banning Eyre reached lead singer Zithulele “Jovi” Zabani Nkosi by telephone from Johannesburg to learn more about the group. Here‘s their conversation.

Hello, Jovi.

Yeah, man.

How are you today?

I’m good, man.

It’s nice to talk to you. I saw you guys at Sauti Za Busara in Zanzibar not long ago. That was a great night.

Yeah, so cool, man.

We‘ve been covering South African music for a long time, but I must say, you guys are really unique. So to start, just introduce yourself and tell me a little bit the story of the band.

My name is Jovi Nkosi. I’m the lead singer of BCUC. We started in 2003. We were just friends. That’s when we were kind of tired of electronic music because at that time it was just electronic music. It was a bad era for live music in South Africa. And we were fans of live music. We were listening to the rules. We were listening to the agents, you know? But there was that thing that was happening in America that we wanted to replicate in South Africa. So when we started, we were more of a soul band than what we evolved to become.

And it was how many musicians at that point?

I think we were 13 in the beginning.

13? Wow.

Yes. But then a lot of soldiers fell off because soon we discovered that the music industry is not about becoming rich. There are trials and tribulations. So other people didn’t want to go through that. Others, their parents told them, “No, you are not doing this. You have to go to work.” We were left as the lucky, unlucky ones to go through everything.

How many were left after that?

After that, it was four that were left. And then the following year, we were joined by Kgomotso [Neo Mokone]. I recruited her because I thought she could sing like Jill Scott, or even better than Jill Scott at the time. I encouraged her to sing with us, and I told her that we are amazing. She’s not going to regret it. She’s going to be rich. And here we are. She’s still not rich today.

Ah, well. There’s still time. You said that in the beginning, when you had all those members, you were more like a soul band.

Yeah, we were trying to not do neo soul, but soul in a South African way because from the onset, we were never replicators, but we wanted to do something that resonated similarly, with a lot of falsettos and deep bass–something like that.

Nice. So when you recruited Kgomotso to sing, and you were starting on a new path, what was the idea going forward?

At this point, the idea was to sing something that’s going to be palatable and easily accessible to the masses. Because in South Africa around that time, as I say, we were listening to a lot of neo soul, like your Dwele or Maxwell. So we wanted to sing something that was going to be easy on the ear for the people who are listening to that genre.

O.K., but that‘s not really where you ended up, is it? What happened?

I think once we stopped singing in English, everything changed. Because at first we were singing in English and then we were like, “Nah, this English thing is not working.” English doesn’t have the expressions and the poetry that our language has. And because we’re telling the stories of the people, it was imperative that we start using the language of the people. And when we started doing that, we fell in love with our music again.

And it just went Afrobeat way a little bit, but the real Afrobeat, like Fela. And the drums, became important. We started adding drums, adding drums. Instead of using Western instruments, we just added drums, added drums. And we were using the guitar, but also the guitar was putting us too mainstream and a little bit more jazz. And jazz in South Africa is known as the music of older people.

Right.

And we were trying to not be playing music of older people. [Laughs]

I get that.

Yeah. And then I don’t know how punk got us. Then it just started becoming punk.

But using native language. What language are we talking about?

Zulu, Xhosa, Sotho, Tswana, Pedi. And then we put some words of ndebele, some words of shangaan, some words of Swazi. We found ourselves just singing in all the languages of South Africa.

That’s great. Roots punk. What year are we up to now?

We are around 2012. 2008 was when we are starting to travel. And as we are traveling to play live the way we want to play, it means we have to loosen up, and get unhinged. So as you get loose, you get unhinged, because it’s resistance music most of the time. So it begins to have an attitude of punk and edge and the necessity to come across, whether it’s going to go down well or it’s not going to go down well. Because in the beginning, this thing we were doing was forever strange. But we insisted that we’re going to do it like this, and that attitude ended up becoming the attitude of our music.

We going to do it like this. As I am speaking now, that’s how we were singing. “Come on, man! Yah, yah yah!!”

Very emphatic. I got it.

Yeah. And then because we had the blues, and we always had funk in our back pocket. Once you get blues, funk comes in. And then the blues becomes the cry. We think that Africa started the blues. We think that the Africans that were taken as slaves to America, they didn’t create this music that they ended up singing in America. We don’t have proof, but we suspect that it was the music that they were singing from here at home. The thing that changed was the language. They brought the music with them.

O.K.

And then we started to claim that attitude. We started to own it. Because sometimes when you do the blues, like, you become guilty. You feel like, “Oh, now I’m doing American music.” But once you start owning it, it automatically stops sounding like America. So it sounded like us. By the time we are already addicted to this sound that we are doing, addicted to these feelings that we are having when we’re on stage. It was just a matter of time that if people discover us, they will discover why we love doing what we are doing.

That’s for sure, man. I’ve been hearing about you guys for a while, and listening to the recordings, but when I saw you live in Zanzibar, then I really got the message.

Yeah. We are a live band. We are still learning how to record. We are a band that is better experienced live. But this new album, at least it has similarities to our live shows.

It’s an interesting album. What was your idea? You say you’re still learning the best way to record. What did you try on this album?

The concept was we don’t need a sound engineer who is a producer. We need a sound engineer who is going to hold our concept and capture our concept. We are a very improvisational band, so we needed a sound engineer that’s going to capture us as we are doing our freestyles. Because some of the songs there on the album are just freestyles. We know those songs now, because we had to learn what we improvised in the studio.

You had to learn it to perform it live.

Yes, and when you learn it to perform it live, we feel like we don’t owe any allegiance to it sounding exactly as it is recorded. Because whatever we recorded, it just becomes the base of what is going to be on stage. So we remember all those things and take all those things, but we add and omit other things for the live show. Because for the live show, there are other things that need to work.

The recording is just a starting point.

Yes, it’s a starting point.

So what about the title, Millions of US?

O.K., now we’re going to our belief. Our belief is that as human beings… Like me, I carry the genes of my mom and my father, who carry the genes of her mom and father and his mom and father. So by the second to the third generation, I’m already carrying about eight to 16 genes, individual genes. So, like, when you multiply that by seven of us on stage and everyone that is working with us and everyone that’s listening to us, everyone that loves us, then it just becomes millions of us. We multiply, you know? And we were trying to reach the soul and the mind and the heart of not only whoever is listening, but also their ancestral line.

That‘s beautiful. Speaking ancestrally, I have to ask you, since your name is in Nkosi, you don’t happen to be any relationship to the late West Nkosi, the producer who worked with Ladysmith Black Mambazo and Mahlathini and the Mahotella Queens and others of that era. I ask because he was one of the first people we met when we went to South Africa in 1987. And I know he had a big impact on the music industry.

He had, but no, we are not related. It’s because of him that a lot of amazing artists in South Africa had success. He believed in them. For me, he was the anthropologist of music. He was a giant that never walked without steps that trembled the crowd. Everything he touched became, like, gigantic. So, amazing guy. Amazing man. I wish I was related to him actually.

That’s great. I had to ask. Anyway, let’s come back to the album. I really like the opening song, “The Woods,” which features your singer, Kgomotso. What‘s that song about?

The woods is a metaphor. It’s a double entendre, a metaphor for us. The woods is the hood. It’s like our hood. But because we are in Africa, we are connected to the soil, the trees, and we are people that still use African medicine. We still respect the African ways. So we call it “the woods.” The woods is our hood. This is a song about the continuation of the struggle, and as we go forward, it seems like it’s becoming more difficult. But it needs to be more difficult because you are going forward. As you are going forward, you are going to the thickness of the forest, and in the thickness of the forest, it’s not going to be easy. You still have to push.

We are also addressing things like the drug pushers in the hood. They are disturbing a lot of potential that could be had. We are pushing against self-hate, because if one from my hood makes it their job or their mission to stand in our way, then it’s not good for all of us. We are pushing against those things. And we are also trying to say to people, “Hey man, just be you. And do you. Everything is going to be O.K., but it’s going to take time. And sometimes you will lose. But it doesn’t mean if you lose, you should stop.”

Amen to that. How about the song “Pieces of Ish.”

Woooo! Self-destruction! Something like this, because it says most of us, we are toxic pieces of s$%#. We are sabotaging our every relationship and when they each hit the fence, they will cry foul. Goddamn it, we are full of sh&%*, basically. So like the hypocrisy that we as the people are living…. We are not doing things that we know we are supposed to do. We’re not stopping to do things that we know we’re supposed to stop. The result is always not right. Yet we are still looking for somebody to blame, and we have to fix ourselves.

That’s strong.

And I have to assume that there’s a political message in the song “Ramaphosisa.”

Highly political. Highly political. It’s about our president, man. Our president is an amazing businessman and a very educated guy, emotionally. He knows how not to ruffle feathers, but he will never stop messing us all up. He is an amazing guy that we should look up to. But the thing is that the intent that he says he has is questionable, because the result is always to the detriment of South Africa. He was involved in killing the miners and Marikana. He did not call the shots to kill them. No, he did not call the shots, but he knew that the miners were in trouble, and he did not warn them.

We still don’t know who actually gave the order to shoot the miners. But we know that he is one of the big shareholders of that mine, and the mine workers died. And me, I put it strongly and I will take the fire that comes with it. Me, I am saying that for the fact that he has financial gain in that massacre, then somehow he is guilty. And the fact that he is even a president of South Africa–that means the ANC is losing its direction. So this is what we are saying in “Ramaphosisa,” Ramapho is Ramaphosa, and to “posita” is to lie. So like we are saying he is Mr. Lies. This is not accusing him. We are just insinuating that he knows what is happening.

Also now in South Africa we don’t have electricity. We are running short of electricity. How can we run short of electricity when we’ve got so much coal? And he agreed on terms that did not benefit the people of South Africa. He agreed to stop using coal, and when we stop using coal, that means we stop more electricity on the grid. If we have less electricity on the grid, then the grid is going to break down. And instead of building new electric farms, he is busy trying to fix machines that are already broken. Like, it’s years now. He should just build new machines because the money that he is using would have built maybe about eight or nine power stations by now, instead of fixing things that he and his friends broke.

Like I say, I think I’ve got love and dislike for him because his hands are forever clean. His hands are forever clean. But by virtue of being in the highest office, that means you know what is happening. He can just shake his shoulders and say, “Look, I don’t know what is happening with the minister of what, what…” But when he is in the highest office, he can’t say that. He can’t. So this song potentially is going to put us into a lot of trouble with the ANC. But what do we do with music if music cannot tell the truth?

Well, that’s very interesting. I want to talk about that because having known South African music since before apartheid, I know there have been different times when people could not speak out, or when they had to be clever about hiding their messages to avoid oppression. I think after apartheid fell, some people thought that musicians weren’t political enough. They were just celebrating all the time. So what is it like now? Do you worry about making a song like that, that there might be repercussions?

Yeah, we worry. We worry because we are from Johannesburg. And in Johannesburg we already have lost about three mayors that died. South Africa is a mafia state. It’s not a secret. The one with bigger balls and access to gangsters in the street will be untouchable. You know? So we worry. But we also know we are part of the world community. And whatever we are saying, we never talk to older people as if they are our age. We respect them and we recognize that the president is an older person than us. But that being said doesn’t mean he is immune from being criticized.

You said you lost three mayors.

Yes. They died. Car accident, sudden sickness. And we know South Africa he comes from the school of apartheid, Ramaphosa himself. His advisor is a guy called Roelf Meyer. Roelf Meyer was an advisor for National Party, the party that was sitting in office and looking to not abolish apartheid. That was the party in power when you people were protesting for freedom of South Africa. That is the party that was not granting freedom to the South Africans.

Yes, I remember.

So that guy who was advising President de Klerk is now advising President Cyril Ramaphosa. So we are coming for him hard on that song.

You said earlier the struggle continues. But in the world of music and culture, do you feel like other artists are being brave and speaking out about this stuff, in the world of hip-hop maybe?

There’s more people that are speaking covertly, because people don’t say exactly what they mean, but when you hear it, you know what this person means. So I suspect we are the first ones to just go and just straight up say it.

Well, that’s brave of you. I hope it goes well. I understand that it’s a difficult time in South Africa. You’ve been through a lot and you’re still in the woods, as it were, right?

Yes, that’s it. It’s going to be O.K. because we believe if we keep on talking about things without saying what those things are, then those things don’t get fixed. The only way you can fix things is when you say things as they are. It would be unfair when you ask me, “What is your problem?” And then I start talking to you in similes and metaphors. What is my problem? I should answer what is my problem? So I suspect that we are at the crossroad now where we need to fix the country. And to fix the country means that the guys who are in office just for their self-benefit. I suspect and suggest that their time should be over.

Because we have fought against apartheid, we can’t be busy ruled by these classists. Your voice matters in South Africa if you drive a Range Rover, or if your mother has got how many millions in the bank, or if your grandfather was so-and-so. So all of us, the ones from the hood, who should we talk to? Because now everything is being spoken about in fancy, shiny places. But the votes are coming from the dirty, angry places.

I hear you, man. Well, you‘re doing important work…

…and dangerous work. But it’s only that song, though. Just that one song is exposing us. That’s why we haven’t even started performing it yet. We still are not brave enough to perform it.

That’s tricky.

No, it’s not tricky. There is a method to this madness because not so many people buy our music. Not so many people will know that song.

I see. Well, that brings me to another question. Talk to me a little bit about the South African music industry, the music scene today. How do you fit into it? We‘re in the time of amapiano now, but there‘s a lot else going on too. What’s your place in it all? How are you received by the people who run the music industry?

It’s dicey, difficult. It’s a challenge. Every promoter and booker loves us, so everybody loves us, the people that should know about us. But the problem is that they are not prepared to pay us the money that we say we want. And I understand why they are not prepared, because our audience is not that great. On Facebook, we’ve got 18,000 people. On Instagram, we’ve got around 8000 people. So it’s understandable why they are reluctant to pay us the money that we are asking for. We understand that. But the problem is, every time when they put us in front of the audience, we will capture that audience and we will make them look so amazing because everyone will have the best time of their lives. Everyone will change their perspective of life and everything, and everyone will go back home warm and fuzzy. You know what I’m saying? For us, that is value, but for them, value is in the algorithm. So this is where we are in the music industry in South Africa.

Wow. Well, speaking of that, I told you that I saw you were in Zanzibar. What was your experience of that festival? I don’t know if you got to stick around and check it out some, but what was your experience like in Zanzibar?

That was our second time playing there. We love that festival. We also love what it is trying to do for the island. Because that festival is not only about music, it’s also about creating opportunities for the islanders, and they’re putting a lot of islanders on stage. Potentially, they will change, or have changed, the lives of the musicians. Maybe five musicians a year, their lives get changed. And if you change five musicians’ lives, you have changed more than like 15 families’ lives. Because, let’s say a band has got seven people. They’ve changed seven families’ lives. The other band has got four people. They’ve changed four people’s lifes. So they are doing a good job.

It’s true. We went to that festival back in 2004 when it was just starting. And we hadn’t been back until this year, and it was just amazing to see the growth. It‘s exactly what you’re talking about. They’ve made a huge difference.

Yes. And now also, it has brought attention to different styles of music, in Tanzania and in Zanzibar, in Kenya. It’s good. It’s good for the region. It’s an amazing festival. And the guys that are doing it, they are not getting rich out of it. They are still doing it because they love it, because they are trying to help.

They are true believers.

And those are the people that we don’t mind to play for. And they pay us whatever they can afford, because they are doing what we are trying to do. So playing for them, it’s not for coming back home with how much. It’s for planting the seeds. When we go there, we are one of the bigger bands there.

That’s right.

A lot of bands come to see us because they’ve heard of us. They are first time seeing us and they learn stuff about our stagecraft and they learn stuff because our music is so different. They become confident if they are also playing something different.

That’s great. Love that. So, one more question about the album and the way you’ve put it together. For the song, “Millions of Us,” you have the long version, almost 20 minutes, and then you have it broken into three shorter pieces. What was the idea there?

The idea of breaking it into three pieces is to make it accessible to the age of the internet. That it’s for internet purposes, for the listening span. But if we can behave like chefs, we would like it being eaten in 20 minutes.

I understand. Are you doing videos for these songs?

Not yet, but we’ve recorded them live, some of them. We are in the process of editing stuff. We’re still looking for someone that will take this as what it is, and just combine it.

We’ll be watching for that. I see that in the past, you worked with Nyami Nyami Records with our friend Charles Houdart in France there, right?

Yes, we did.

Cool. He‘s doing interesting stuff. Jovi, it’s really great to talk to you, and I look forward to seeing you over on this side one of these days.

We are coming to the U.S., with Center Stage, where they take artists from other countries and they come to play in the U.S..

Yes, we know about Center Stage. We‘ll be looking for you.

Thank you. Peace, Banning.

And peace to you. Bye bye.