Is Kendall Roy a fashion icon?

The idea that the weak-willed scion of “Succession” is a figure whose wardrobe is worthy of emulation is an amusing realization to Michelle Matland, the costume designer for the HBO drama that tracks corporate and familial ladder-climbing of the fictional Roy dynasty. After all, Kendall’s fashion choices — like a pair of pricey Lanvin sneakers purchased to impress the founders of an art start-up or the enormous Rashid Johnson pendant he dons like a talisman of virtue signaling — are used to relay his cluelessness and insecurities.

“These are costumes, not fashion,” says Matland. “And so it’s very interesting that they become fashion.”

In other words, Kendall’s clothes are not meant to be aspirational, but rather tell us how desperately he’s trying to belong. But somehow, his expensive bomber jackets and cashmere baseball caps have made him into the face of America’s biggest fashion trend: the “quiet luxury” movement.

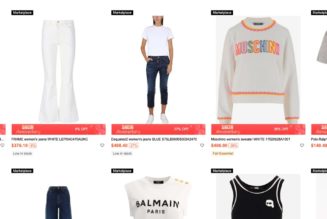

Across TikTok, creators opine that the luxury logomania that thrived over the past several years — putting a Balenciaga logo hoodie over a Supreme T-shirt and Gucci-print sweatpants — is hardly the uniform of the one percent.

“This is not luxury fashion — that’s a billboard,” says creator Jansen Garside in a video from late March. Instead, he says, the wealthy buy “quiet luxury, where the luxury aspect comes in the form of incredibly high-quality materials, construction, and reputation.” As another user, sherhymeswithorange, described the look, “‘I’m so rich, I don’t even need to tell you how rich I am’— otherwise known as quiet luxury.”

Instead of Gucci and Balenciaga, creators direct viewers to the Italian brands Brunello Cucinelli, whose T-shirts and tailoring are beloved by Jeff Bezos and Mark Zuckerberg, and Loro Piana, whose Gift of Kings fabric, which is visually indistinguishable from your average wool but promises an “infinite lightness” that is softer to the touch than cashmere, is cut into T-shirts and sweaters that sell for upward of $2,000.

Matland says that in researching the show’s costumes, she and her team followed one percenters into stores like Brunello and Loro, “and we would literally kind of mimic what they were touching, feeling. And it is so much textural.” The appeal of clothing to this kind of person, Matland says, is “just in the fabrication of the garment. And obviously, certain cuts are going to be minimalist and refined just based on the styling.”

Though quiet luxury (and its siblings, “stealth wealth” and the “old money aesthetic”) have been topics of conversation on social media for almost two years now, the idea has become even more discussed since the premiere of “Succession’s” fourth and final season. A number of creators demonstrate how they get the quiet luxury look — “people with quiet luxury wear tailored pieces often in monochromatic tones,” explained Liz Teich, a.k.a. thenewyorkstylist, in a quiet-luxury explainer that’s been viewed on TikTok more than half a million times as she loops a black leather belt into a pair of cream high-waisted trousers and throws on a tobacco-colored blazer — to a soundtrack of the show’s opening theme. A number of these videos are hashtagged “successioncore.”

The idea was further popularized by Gwyneth Paltrow’s ensembles throughout her highly watched ski trial, when she arrived in court wearing subdued blue Prada blouses and skirts, and oversize coats by the Row. Vogue, the New York Post, Time Magazine and the Daily Mail have all written recent guides to quiet luxury, extolling the virtues of starkly plain $1,390 Tom Ford hoodies and $625 Loro Piana cashmere-blend baseball caps.

“Succession’s” latest season even provided its own allegory on the quiet luxury versus logo-crazy dynamic in its opening episode, when Greg’s date, an arriviste named Bridget, attends Logan Roy’s birthday party with what Tom Wambsgans deems “a ludicrously capacious bag” in a screeching Burberry plaid that, in the Roys’ world, telegraphs the item’s cost and therefore, her poor taste.

The idea that the American elite embrace a way of dressing that is coded, designed to be understood by only their fellow one percenters, is nothing new. If the American Dream means that anyone, theoretically, can aspire to expensive clothes, how do the truly rich signal their status? Counterintuitively, by wearing understated or even worn-down clothing.

Edith Wharton’s books carefully chronicle the ways that upper-crust Manhattanites at the turn of the 20th century dressed to ensure their look was inaccessible to anyone who merely had money, refusing to wear new clothes until they were a few years old. (In fact, streetwear fanatics often treat their new Supreme merchandise the same way, “putting it on ice” until the hype has mellowed.)

Maggie Bullock, author of the new J. Crew history “Kingdom of Prep,” describes how students at Ivy League universities in the early- and mid-20th century — the era from which J. Crew took inspiration — would wear their most-worn-in clothes as a point of pride. “It was all about how slouchy it was, and how broken-in it was, and you didn’t want it to look new, and you didn’t want to look like you tried too hard,” she says. “They could afford to dress that way because it wasn’t going to knock them off their social platform or their rung of the ladder. They could afford to almost flagrantly play with their presentation.” Someone who wasn’t White or rich, in other words, had to look “presentable” or had to “try”— a classist reality that is also percolating in the quiet luxury discourse.

Emily Cinader, the daughter of J. Crew’s founder who would lead the company through its first golden period, in the 1990s, had such an understated sense of style that employees well-versed in the vibrant pouf skirts of Christian Lacroix and the pastel, pony-embroidered polos of Ralph Lauren thought she was badly dressed: “They thought that Emily was a super boring dresser,” Bullock says. “Like, there’s nothing to this.” Perennially makeup-free, she favored white button-downs, gray trousers, and chunky loafers — quiet luxury, in other words — and colleagues were even encouraged to remove any bracelets before entering her workspace so that they didn’t clang in distraction. (Sounds like material for a Roy family eccentricity!) That period, unsurprisingly, is newly trendy for its minimalist and unfussy classics, which is now lionized by fashion fans and Instagram accounts like @lostjcrew and @simplicitycity.

And unpacking those codes, as creators are now obsessively doing on social media and editors in magazine pages, is almost an American rite of passage. Podcaster Avery Trufelman recently dove into the anthropological obsessions with class and “American style” on the latest season of her show “Articles of Interest,” tracking how in the 1960s, Japanese retailers came to Ivy League campuses to capture the frayed chinos and sun-bleached rugbys worn by students, and created the book “Take Ivy,” which has since its 1965 publication become a permanent fixture on American menswear designers’ mood boards. Similarly, Lisa Birnbach’s “The Official Preppy Handbook,” first released in 1980 and now considered a cult classic that sells for upward of $300, broke down the habits of dynastic WASPs decades before “old money TikTok” was a thing. Intended as satire, the book accidentally became a manual for those outside WASP inner circles to learn about boarding schools and the art of layering L.L. Bean pullovers. Perhaps it’s a way to insist that, no matter how complicated or arcane the sartorial codes of the rich get, they can and will be made accessible to all. “The really American thing about this,” says Trufelman, “is the potential attainability of it.”

Or perhaps the difficult truth is that we all just want to look rich, or at least know what they look like. Income disparity may be at a historic high, but it feels as though the wealthy are less visible than ever. Other than the dysfunctional family we see on television every Sunday night, the one percent is almost out of view, especially for those who have spent the past few years learning about clothing (and status) through social media.

There is also a sense of shock that the name brands we know well, and which have been marketed to us as signals of success, are not. Instead, a vast conspiracy of secret brands we’ve never heard of is being worn by countless billionaires. In fact, the brands often name-checked in these videos — Brunello, Loro, Akris, Khaite — barely qualify as elite for people with an extreme amount of money.

Tiina the Store, in the Hamptons enclave Amagansett, has become something of a refuge for one percenters who are horrified by the obvious excesses of neighbors who have a more showy relationship to their wealth. “I’m sure you know what’s happening in East Hampton,” says Tiina Laakkonen, who founded the store in 2012, referring to the appearance of Gucci and Prada on the town’s main commercial drag. “Maybe at one point in their lives, Hermes meant something to them, but I think today, they are not interested in that world. It’s almost like, it’s a little nouveau riche for them.”

Their husbands may still gravitate to Loro and Brunello, but her women customers wear what she refers to as “a parallel universe of brands,” like the Arts&Science, a Japanese brand of workwear-inspired, soft tailoring; Casey Casey, a Paris-based line of simple cotton skirts and blouses; and Wommelsdorff, a collection of hand-knit, almost naive sweaters that cost up to $2,450.

“The idea that you are wearing something that nobody else knows exactly what it is [or] where you got it — they like [that],” Laakkonen says. “They like the idea that, I’m the only one who has this.” What they look for, Laakkonen says, is “uniqueness, and that feeling when it looks kind of like nothing and [it’s] simple, but you know it is the most beautifully made, in the most beautiful material.”

These are the kinds of brands that Jeremy Strong, the actor who plays Kendall Roy, often mixes into the wardrobe of his character as he collaborates with Matland — brands like Geoffrey B. Small and Haans Nicholsa Mott, who make what’s often called “slow fashion” for its seasonless, trend-averse appeal. Kendall, at least in terms of his wardrobe, is right on the money.

But why does this obsession with the wardrobes of the wealthy persist? “Because we’re interested in anything we can’t have,” Matland says. “I would love to have a million bucks too.” She laughs. “I think we inherently always want to reach a little higher than where we are, just by nature of being human. It’s not a negative. We always want whatever is just unobtainable.”

If Matland had a million dollars, would she dress like a “Succession” character? Without missing a beat, she answers: “No.”