Mondays With Morgan is a new column in London Jazz News written by Morgan Enos, a music journalist based in Hackensack, New Jersey. Therein, he dives deep into the jazz that moves him – his main focus being the scene in nearby New York City.

This week, Enos reviewed two sets by South African pianist and composer Bokani Dyer and his ensemble on 29 April at Dizzy’s Club at Jazz at Lincoln Center, the second night of a three-night residency — and interviewed Dyer and featured tenor saxophonist Melissa Aldana — as well as Seton Hawkins, the Director of Public Programs at Jazz at Lincoln Center. Bokani Dyer’s new album, Radio Sechaba (Brownswood) is released on 12 May.

When Melissa Aldana received an offer to accompany South African pianist Bokani Dyer, the prospect amounted to uncharted territory.

The Chilean tenor saxophonist, who’s lived in New York for 13 years, had never played with South African musicians. And while she attended Berklee College of Music with Dyer’s South African bass player, Zwelakhe-Duma Bell le Pere, she had only been aware of Dyer in an ambient sense.

That all changed when Jason Olaine, the Vice President of Programming for Jazz at Lincoln Center, asked Aldana to accompany Dyer at Dizzy’s Club — the logic being that Dyer, who’s just now gaining traction stateside, could use an established New York cat in his corner.

Out of a handful of worthy candidates, it was Aldana who ended up available to play — and all involved were lucky she was. An exquisite and deeply personal communicator on the horn, Aldana released her debut album for Blue Note, 12 Stars, in 2022 to deserved applause.

The last time Dyer performed in New York was 2019, in a shared set with South African multi-instrumentalist and composer Hilton Schilder. On 29 April, he came roaring back in his first major New York run where he’s a major headliner — with Aldana as his co-pilot.

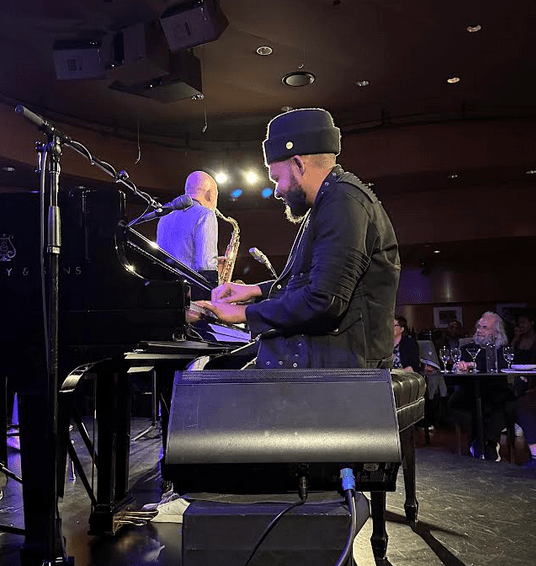

This week, Dyer took Dizzy’s stage in two different contexts. The first was as part of his father, tenor saxophonist Steve Dyer’s group, Genesis of a Different World, in commemoration of South Africa’s Freedom Day. The second put Dyer’s mastery as a bandleader front and center.

His lineup has slightly varied from night to night, but for two sets on Saturday evening, Dyer performed with Aldana, bassist Zwe Bell le Pere and drummer Kush Abadey — with the elder Dyer guesting for a few tunes each on the double-tenor line.

Dyer is currently ramping up to the release of his new album, Radio Sechaba, out 12 May on Brownswood Recordings. Multifarious and genre-straddling, absorbed in the theme of nation-building on interpersonal and intrapersonal levels, tunes like “Ho Tla Loka,” “State of the Nation” and “Resonance of Truth” mark a major evolutionary step for Dyer.

But the audience at Dizzy’s didn’t simply get a preview of Radio Sechaba, as enticing as that would be.

In both sets, Dyer performed only the album’s meditative closing track, “Medu,” an expression of solidarity and paternal love, with rich harmonic and timbral contours courtesy of the two tenos. The composition carries tremendous personal weight for the pianist.

“I was born [in Botswana] at a time when there were a lot of activists who had left their home — including my dad,” he told LondonJazz News between sets. “Fighting the struggle in exile, not knowing if they would ever be able to return home. That song, ‘Medu,’ is a big part of our connection to each other.”

The lion’s share of Dyer’s setlists took a spin through his back catalog. The percolating “Hyacinth,” from 2020’s Kelenosi, is a tribute to Bheki Mseleku, titled after the trailblazing South African pianist and multi-instrumentalist’s middle name.

“Dollar Adagio” pays homage to another Mount Rushmore figure thereof: pianist and composer Abdullah Ibrahim, formerly known as Dollar Brand. “Adagio is kind of a laid-back tempo marking,” Dyer explained. “It was referencing his kind of style, where he leaves so much space in the music and takes his time.”

Dyer wrote “Vuvuzela” — from 2015’s World Music — after South Africa hosted the World Cup in 2010; its repeated notes evoke the clamorous plastic horn. “Hope Spring,” released as a single in 2020, swirls with optimistic energy. The roiling “Waiting, Falling,” also from World Music, is a reference to how the melody relates to the countermelody.

As for the deliberative “Keynote,” from the same album?

“There’s something called a kgotla back home, where the clan gets together, and this is where things get decide if there are disputes or things to discuss,” Dyer explains. “But it’s not an autocratic gathering; it’s something where everyone gets to speak, but the chief gets up to give the main address — the keynote.”

For “African Piano,” from 2011’s Emancipate the Story, Dyer prepared the piano with sheets of paper to render the strings rattling and buzzing.

“I’ve listened to a lot of West African music — Malian music in particular,” he explained backstage. “The way they play the kora is something that I was very inspired by. I’m also thinking about the mbira, which sometimes gives that sound as well.”

As Seton Hawkins, Director of Public Programs at Jazz at Lincoln Center, explained, this concept runs incredibly deep.

“About a decade ago, Bokani began to explore the question of the piano as it related to Africa. The piano, on paper, is sort of the alchemy of Eurocentric music — the device by which chromatic music and tonal harmony of the Baroque era was codified.”

But to South Africans at the helm of emerging jazz idioms, it’s a completely different story. When missionaries set up schools with pianos, they developed a decidedly non-Eurocentric relationship with the instrument.

“For a number of artists, the possibility that the piano could, indeed, be a deeply African instrument had become clear to them,” Hawkins said. “Bokani was looking at some of the other melodic traditions more broadly.”

Aldana was born in Santiago, and her music is steeped in her Chilean heritage. With that in mind, how does South America connect to South Africa, as far as their jazz traditions go?

As Hawkins explains, there are traditions shared between these areas due to forces directly related to the transatlantic slave trade. For instance, the berimbau of Brazil and the uhadi of South Africa — both single-string percussion instruments — are functionally the same instrument.

One spiritual link between Aldana’s artistry and South African music is in the primacy of the tenor saxophone, and her particular approach to it.

“The tenor saxophone bench in South African history is deep, and it is extraordinary,” Hawkins said, citing titans like Winston “Mankunku” Ngozi and Duku Makasi. “What you’ll notice with them is they’ve got a big, rich sound, but they also have a hyperfocal quality — falling off of notes, and bending notes, and sliding into notes… Melissa does that too.”

Backstage, Dyer called Aldana “an incredible musician who is just so focused and aware all the time,” and Hawkins echoes this sentiment. “A good tenor saxophone player can play a billion notes really fast,” he said. “A great tenor saxophone player chooses not to do that. And that’s Melissa Aldana.”

Speaking of bending and shaping notes in real time: Blue Note president Don Was didn’t call Aldana “a beautiful singer” (*) for nothing. Her conversational, lyrical style also connects her to South African musical expression in a major way.

“They’re not as interested in playing in fast, bebop styles,” Hawkins says of players exemplified by Mankunku. “[They prize] all those things that feel like the human voice.”

Dyer closed both sets with “Bua,” which means “talk.” It’s his newest tune — one even newer than Radio Sechaba. Despite, or because of, the composition’s theme of suffering in silence, Dyer’s performance was utterly ascendant — it exuded a glorious sensation of release.

And at the end, Dyer began literally singing — a relatively new form of expression for him. “He’s drawing on Tswana traditions,” Hawkins says, noting that he sings in that language. “To my mind, he’s continuing a lot of what he had been exploring with [his 2018 album] Neo Native with Radio Sechaba, and he’s now adding vocals into it.”

As tourists from all over the world frequent Dizzy’s, it’s safe to say many in the audience aren’t immersed in South African jazz and its attendant context. But they clearly felt the music. And if one wants to venture further into this universe, Dyer’s set opened a multitude of portals.

“There is something going on in the South African scene right now that is breathtakingly creative,” Hawkins said at closing time. He paused to wave to Aldana and Kush as they exited, instruments slung over their shoulders, into the drizzly Manhattan night.

“And Bokani is easily one of its best musicians,” he said.

LINK: Bokani Dyer’s “Radio Sechaba” on Bandcamp