Hermès is among the three luxury-goods companies that together snagged the majority of incremental revenue in 2022.

Photo: Edward Berthelot/Getty Images

In a world coping with inflation, war and bank runs, it seems counterintuitive that demand for luxury is still running hot.

Yet in recent days, two big designer brands reported bumper first-quarter sales. Paris-listed Hermès said its revenue grew 23% from a year earlier in the three months through March, ahead of the 13% analysts were expecting. At LVMH Moët Hennessy Louis Vuitton—owned by Bernard Arnault, the world’s wealthiest person—sales grew 17% in the same period. This was also much higher than analysts had forecast.

Even before these results, European luxury stocks were on a tear, gaining 23% on average this year compared with a 14% rise in the MSCI Europe index.

Many shareholders see Europe’s luxury brands as a good way to gain exposure to wealthy Chinese consumers, who are keen to shop again after almost three years of pandemic disruption. LVMH said sales in China at fashion brands such as Louis Vuitton, Christian Dior and Celine increased more than 30% in the first quarter compared with a year earlier.

Chinese consumers have accumulated spare cash, which could help to drive sales for the rest of the year. According to Bank of America estimates, in 2022, household deposits in China increased by 7.9 trillion yuan, equivalent to $1.15 trillion at today’s exchange rate—much higher than annual averages of around 2 trillion yuan.

Ultrawealthy consumers are now propping up the luxury-goods industry, with signs of weakness lower down the income ladder. According to Bernstein analysis, people who spent up to 1,000 euros on designer goods in 2019 slashed their budgets in half in 2022. Meanwhile, spending at the top is booming. A wealthy shopper who shelled out around €50,000 in designer shops in 2019 spent €135,000 in 2022.

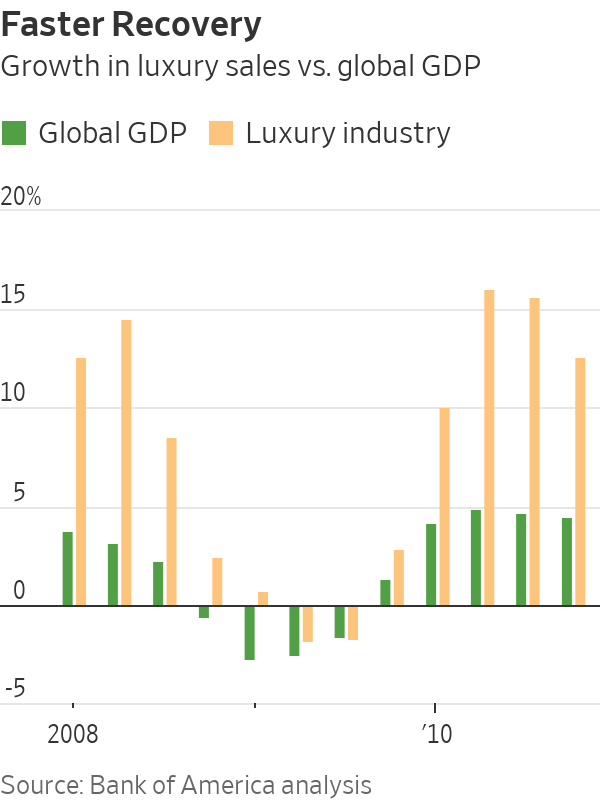

The luxury industry has been surprisingly resilient in previous economic downturns. In the global financial crisis, the sector had two quarters of lower sales before it began to grow again, while global gross domestic product contracted for four.

But current trends are out of whack with long-term averages and might not be sustainable. In the decade before the pandemic, the luxury sector typically grew at double the rate of global GDP. This year, bullish analysts expect luxury industry sales to increase by 8% to 10% compared with the International Monetary Fund’s 2.8% forecast for global growth. Other pockets of abnormally strong demand seen during the pandemic—such as for rented housing in the U.S.—are beginning to unwind.

It will be harder for luxury brands to flatter their top lines with additional price increases after they hiked aggressively in 2021 and 2022. And unusually generous ad budgets—European luxury-goods companies spent 33% more on marketing in 2022 than a year earlier—might not last either.

Demand is likely to become patchier among brands, so investors should be choosy. Last year, three companies—LVMH, Hermès and Richemont—took home 75% of the industry’s incremental revenue, according to Bank of America analysis. When rivals, including Burberry and Gucci-owner Kering, report their results over the next few weeks, it will become clearer who is winning or losing market share.

Luxury is still shining in a roiled world, but maybe for a narrower selection of brands in the future.

Write to Carol Ryan at carol.ryan@wsj.com