In 2014, Lana Del Rey told a journalist that she wished she was dead, and for what seemed like years after, scarcely an article was written about her that didn’t mention it. Back then, the singer was still miserable at the sour critical reception of her debut album. She was, perhaps, peddling its underlying fatalism, pushing back on allegations that her noirish Born to Die persona was fabricated. Almost certainly, she was harboring the sort of creative ambition that craved association with tragic geniuses like Kurt Cobain and Amy Winehouse.

Lana has lived many days since then and seemingly found some of them worthwhile. In due course, particularly since the release of her 2019 national pulse check Norman Fucking Rockwell!, her songwriting received the recognition she always knew it deserved. In conversation with Rolling Stone this month, Lana described a great unburdening in her psychic space. She is still talking—and singing—about death. But now, rather than an escape hatch, it’s a framing device through which to peer at her life. “The Grants,” which opens her ninth studio album, climbs to the metaphorical mountaintop, guided by John Denver’s sense of mystical wonderment, to receive wisdom from on high. “My pastor told me when you leave all you take is your memory,” goes the chorus, resolute like a hymn, wrapped up with gospel backing vocals and orchestral ribbons, “And I’m gonna take mine of you with me.” To whittle the raw material of life into meaning, worth preserving—this is the writer’s task.

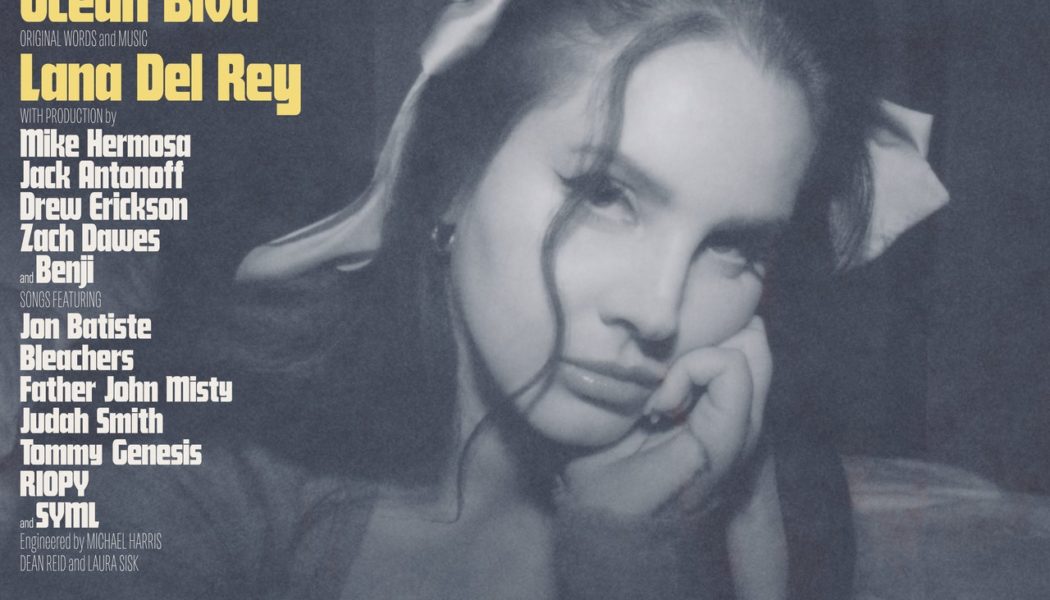

It’s one that Lana takes up vigorously, even if that meaning is sometimes legible only to her. Did You Know That There’s a Tunnel Under Ocean Blvd arrives as a sweeping, confounding work-in-process. It’s full of quiet ruminations and loud interruptions; of visible seams and unhemmed edges, from the choir rehearsal that runs through its opening moments to the sound of the piano’s sustain pedal releasing at its end. Beauty—long Lana’s virtue and her burden—fades or is forgotten, like that titular tunnel, its mosaic ceilings and painted tiles sealed up and abandoned. Here, Lana is after something more enduring, the matters “at the very heart of things”: family, love, healing, art, legacy, wisdom—and all the contradictions and consternation that come along with the pursuit.

Blue Banisters, Lana’s album from 2021, introduced many of the ideas that stand out here: revisiting old material with new relish, releasing pop’s conventional structures and polish, writing about loved ones with tender specificity. Lana, née Elizabeth Grant, opens Ocean Blvd with a track that bears her family name, and she holds her father, brother, and sister close throughout, as if bracing for loss. On one song, she exhales a prayer amid jazzy squiggles, calling on her grandfather’s spirit to protect her father, a maritime enthusiast, while he’s deep-sea fishing. She entreats her brother Charlie to quit smoking. The matter of bearing children—her sister’s daughter and Lana’s own hypothetical offspring—comes up repeatedly, on “The Grants” and “Sweet,” a tradwife fantasy tucked in a mid-century movie-musical score. “Fingertips” broaches the topic of motherhood with a devastating admission of self-doubt: “Will the baby be all right/Will I have one of mine?/Can I handle it even if I do?”

Such a sentiment could easily be extrapolated into a comment on millennial unease, but this feels more personal. It’s Lana, a self-made emblem of vulnerable womanhood—in her own words, “a modern-day woman with a weak constitution”—at her most genuinely unguarded. She was nervous to send early sketches to producer Drew Erickson, she said, and even in finished form, the material sounds like it’s for her ears only. With its solemn hush, meticulously rendered but opaque details, and lack of organizing logic, “Fingertips” seems disinterested in holding our attention. There’s no rhythm, no structure, only the strings and the Wurlitzer picking up Lana’s breadcrumbs as she wanders the misty forest of her own memory.

Elsewhere, Lana throws stones into these still waters, most memorably on “A&W.” She writes from the perspective of the other woman, a familiar figure in her discography—sometimes, a sympathetic lonely heart; here, a symbol of the ire that unorthodox women unleash. “Did you know that a singer can still be looking like a side piece at 33?” asks Lana—unmarried and child-free at 37, a subject of constant physical scrutiny. The title is a fit-to-print stand-in for “American Whore,” and Lana cycles through her many avatars: an embattled attention-seeker, an illicit lover, an imperfect victim (“Do you really think that anybody would think I didn’t ask for it?”). Then, after a radical about-face that steers the song from voice-memo balladry into boom-bap playground rap, she is someone else entirely: a girlish brat tattling to someone’s mom. A critic, albeit a clumsy one, of empowerment feminism, Lana here embodies characters that point to just how little girlbossing has done to remedy societal malice toward women. They reflect an enduring taxonomy, reified in a post-Roe landscape: We are whores who deserve what we get, or else children to be saved from our own decisions.

Where do we go from here? To church, apparently. Lana follows “A&W” with a sermon on lust from Judah Smith, the Beverly Hills pastor and influencer who counts the Biebers (and Lana too) among his congregants. The four-and-a-half-minute homily, accompanied by melancholy piano, is presented with little comment beyond an occasional laugh or affirmation, possibly from Lana herself; given its placement, the track seems designed more to inflame than to enlighten. At the end, though, comes an interesting kernel: “I used to think my preaching was mostly about you,” Smith concedes, “…I’ve discovered that my preaching is mostly about me.”

Now more than ever, Lana’s preaching is mostly about her, reflecting a growing instinct to self-mythologize. On Ocean Blvd, she sings explicitly about being Lana Del Rey, with lyrics like “Some big man behind the scenes/Sewing Frankenstein black dreams into my song” pointing all the way back to the industry-plant allegations that surfaced around the time of her debut. That backward-looking gaze also settles on hip-hop, a longstanding presence in her work that was substantially dialed down after 2017’s Lust for Life. The trap beats are back, at least in the record’s final stretch, where they accompany some of Lana’s most willful provocations. Her lyrics flirt with transgressions that have previously landed her in hot water, within and beyond her music: casual Covid noncompliance, brownface. There’s a sense of doubling down, of insistence that her path is hers alone to forge. On “Taco Truck x VB,” the chimeric closer that is partially a trap remix of Norman Fucking Rockwell!’s “Venice Bitch,” Lana elbows her way in front of the criticism: “Before you talk let me stop what you say/I know, I know, I know that you hate me.” She is fresher yet out of fucks.

Lana is a postmodern collagist and a chronic cataloguer of her references: Take “Peppers,” which samples Tommy Genesis’ ribald 2015 track “Angelina,” name-checks the Red Hot Chili Peppers, and interpolates a surf-rock classic, all in the span of four minutes. At her best, Lana reinterprets others’ work with intention, percolating their meaning through a personal filter. The way that she now applies this same approach to her own past material—beyond the “Venice Bitch” remake, there’s a sliver of “Cinnamon Girl” in the Jon Batiste feature “Candy Necklace,” and chopped-up strings from “Norman Fucking Rockwell” on “A&W”—suggests an artist who is tracing her own evolution and also submitting her work, ripe for reimagining, for entry in the greater American songbook from which she so readily draws.

One of Ocean Blvd’s key takeaways is that perfection is not a requirement for inclusion in this canon. Part of the title track is spent extolling a sublime flaw—a specific beat in the 1974 Harry Nilsson song “Don’t Forget Me.” Lana cites, by timestamp (2:05), the moment when the singer-songwriter’s voice breaks, cracking open the track with raw emotion. As an indicator of Lana’s mindset, this embrace of imperfection may help explain some of Ocean Blvd’s excesses and experiments, which nobly pursue profundity and succeed only sometimes. Still, there are 2:05s to be found within the sprawl.

All products featured on Pitchfork are independently selected by our editors. However, when you buy something through our retail links, we may earn an affiliate commission.