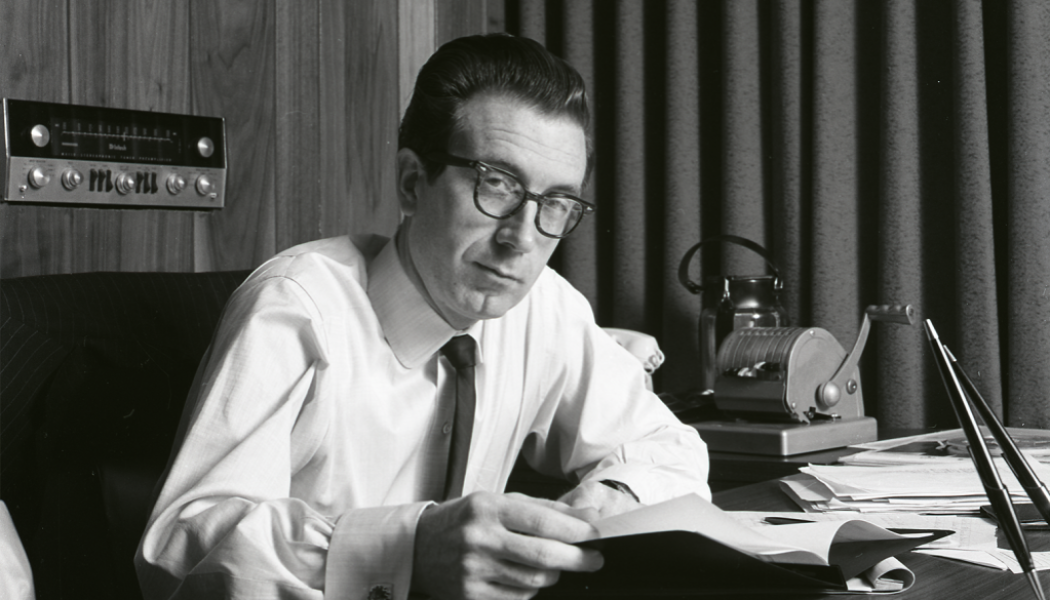

Steve Greenberg, founder/CEO of S-Curve Records, produced “The Complete Stax/Volt Singles 1959-1968,” and box sets devoted to Stax artists Otis Redding and Sam & Dave. He wrote album notes for “Stax ’68: A Memphis Story.” Below, he reflects on a 30-year friendship with Stax co-founder Jim Stewart, who died Dec. 5.

I first met Jim Stewart when I was producing the 9-CD Complete Stax/Volt Singles:1959-1968 box, which came out in 1991. While consulting with him over the phone about the project, he mentioned that legendary Stax songstress Carla Thomas still lived in Memphis, and that he’d really love a chance to work with her again on a record—something he hadn’t done in over 20 years. Almost immediately, I flew down to Memphis, meeting Jim and Carla at the stately Peabody Hotel to discuss the possibility of making a record together. The record never materialized, but a bond began to form between Jim and me.

What initially struck me about Jim was his humility: Here was a man who’d co-founded one of the greatest R&B record labels of all time—who, in addition to running the label, was in the studio producing such classic recordings as Otis Redding’s “Try A Little Tenderness” and Rufus Thomas’ “Walking the Dog.” Perhaps even more impressively, he created an environment at Stax where Black and white musicians could work together in complete equality, all the while situated in the heart of the segregated South during the most tumultuous years of the civil rights movement. Yet, Jim possessed none of the hubris or self-regard typical of many who have achieved greatness or attained legendary status.

Nor did he express an ounce of bitterness, even though his career could be described as a rags-to-riches-to-rags-to-riches-to-rags story: From a modest upbringing in rural Tennessee, he started a record label in 1957 with his sister Estelle Axton originally called Satellite before rebranding as Stax (St+ Ax) in 1961. A string of hits by the likes of Sam & Dave, Booker T. & the MGs, Redding and many more artists brought worldwide fame to Stax, and the label was flying high. But in 1968 Stewart learned that a distribution contract he’d signed with Atlantic’s president Jerry Wexler a few years earlier—without consulting an attorney—had somewhere in the fine print given Atlantic permanent rights to the entire Stax catalog. This calamity occurred nearly simultaneously with the death of Stax’s biggest star, Redding, in a plane crash, and the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr. in Memphis, just a short distance from the Stax studio, causing parts of that city to go up in flames and hastening the demise of the air of racial harmony at the label.

Taken together, these tragedies would have been enough to cause most record companies to shutter. But, together with his new partner, the civil rights activist turned record promo man Al Bell, Jim started Stax Records again from scratch, with the label achieving even greater commercial and critical success in its second incarnation. As the ‘70s dawned, Stax, under Bell’s leadership, became deeply identified with the cause of Black empowerment, and Jim decided it was time to exit, selling his interest to his partner. Now a wealthy man, Jim could have ridden off into the sunset, but a few years later, when Stax began to experience serious financial difficulties, Jim reinvested most of his assets in the label, not being able to bear the idea of his baby’s demise. By 1976, the label declared bankruptcy and closed. Stewart lost nearly everything; his home and possessions were sold at auction in 1981.

When I first met Jim that night at the Peabody, I imagined he harbored no small amount of ill will towards Atlantic Records, the label that had taken away his catalog and was now putting out the box set I’d produced. But no, he said, he didn’t hold any sort of grudge, and when I invited him to come to New York for the launch party celebrating the release of the box set, he was only too happy to do so. The New York event featured a concert by legendary Stax performers and was attended by Atlantic Records veterans who’d been around during Stax’s Atlantic period, including label founder Ahmet Ertegun. Jim offered some remarks from the podium—his first public appearance in nearly two decades—and spoke of what a pleasure it was to see old friends, and what an honor it had been to get to work with such great artists and to have been in business with Atlantic. He even referred to Jerry Wexler as “my hero.” He was the embodiment of grace.

Even after Stax closed, Jim continued in the music business. In the late ‘70s he opened a recording studio in Memphis with former Stax guitarist Bobby Manuel. Eventually, they started the Houston Connection record label, scoring a top 15 Billboard R&B hit in 1982 with former Stax artist Margie Joseph’s “Knockout!” They never had another national hit, but Jim kept at it, producing records locally.

The release of the Stax box brought Jim back into the music industry’s field of vision, and he began to make regular visits to New York, always stopping by to have lunch and to pitch me his newest discoveries. I remember he had a fun record called “Mud Ducks” by Memphis rapper Yan-C which we almost signed when I was head of A&R at Big Beat Records, but in the end the only record I ever worked on with Jim was Lea’Netta Nelson’s “That’s the Way,” a great slow R&B jam that I signed in 1994 when I was an A&R guy at, of all places, Atlantic Records. I had high hopes for that record, but looking back, I think Atlantic only let me sign it as a token gesture to Jim, and it received no attention, only seeing release as a radio promo single. I spoke to Jim shortly after that record disappeared without a trace, and he told me he was retiring from the music business.

Eventually, Jim received his due as one of the great label chiefs of the 20th century. He was inducted into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame in 2002 and made one final public appearance at Memphis’ Stax Museum of American Soul Music in 2019, where he was feted by such Stax legends as Carla Thomas and Al Bell in a special salute.

The last time I spoke to Jim was a phone interview with him for the liner notes of 2019’s “Stax’68” box set, a collection chronicling Stax’s annus horribilus and its aftermath, produced by A&R man/music historian Joe McEwen. Jim was in good spirits, with a sharp recollection of events that happened more than 50 years earlier. He was better off financially, partially due to producer royalty payments for the Stax singles he produced, which began to be paid in the 1990s. Even looking back on that trying year of 1968, he remembered it with fondness. “Most importantly,” he told me, “We still loved what we were doing. We believed it was going to be okay.”

This world will miss you, Jim Stewart. You were a great label executive, a producer of classic records and you believed in the dignity of all people. And you really appreciated that you got to do it at all.

[flexi-common-toolbar] [flexi-form class=”flexi_form_style” title=”Submit to Flexi” name=”my_form” ajax=”true”][flexi-form-tag type=”post_title” class=”fl-input” title=”Title” value=”” required=”true”][flexi-form-tag type=”category” title=”Select category”][flexi-form-tag type=”tag” title=”Insert tag”][flexi-form-tag type=”article” class=”fl-textarea” title=”Description” ][flexi-form-tag type=”file” title=”Select file” required=”true”][flexi-form-tag type=”submit” name=”submit” value=”Submit Now”] [/flexi-form]

Tagged: entertainment blog, Jim Stewart, music, music blog, Music News, Obituary, Stax Records