The current state of NFT art is best described as “visual dogshit,” the artist and provocateur Brad Troemel argued in a recent Instagram slideshow. Nobody actually cares what these images look like, Troemel said, so long as they can be produced quickly in large quantities, while also avoiding risky artistic gestures that might alienate crypto bros.

“The defining production method across all NFTs is that they’re auto-generated as a batch of hundreds or thousands of images to be sold at a time,” Troemel wrote, a strategy that he believes was created to “give a lot of people as little as possible.”

Looking at the viral hype-driven NFT collections, it’s easy to see what he means. The biggest NFT series tend to be procedurally generated cartoons offering variations on a theme: a monkey with sunglasses, a monkey with a gold chain necklace, and so on. These characters are more like intellectual property than art. Like Pikachu or Baby Yoda, they can be endlessly exploited for their recognizability without having to offer us anything new.

This is a common frustration in the art world. In strictly economic terms, NFTs are the biggest thing to happen to art markets in a long time — but most of them are just so insipid that they’d be more interesting if they were actively, aggressively ugly. When investors spend vast sums for a prized token, they are mostly buying bragging rights, more like a rare Fortnite skin than an object of beauty.

But it doesn’t always work that way. Literally anything can be an NFT, even a physical object, as long as it’s tagged to a token on the blockchain. And if you look closer, you’ll find a lot of genuinely interesting digital art that’s been written off because of the general NFT exhaustion.

The critic and curator Tina Rivers Ryan, one of the foremost historians of digital art, told me it’s important to distinguish different tendencies in the NFT space. There’s what she calls blockchain art, which are projects that not only use the blockchain but actively explore its limits to make us rethink concepts like value, ownership, and authenticity (this is the stuff she finds most exciting). Then there’s crypto art, a term she uses for art that celebrates cryptocurrency and its attendant subcultures — ”illustrations of you know, Elon Musk with red laser eyes, or giant gold bitcoins rotating in space.”

Then there’s everything else, most of which is neither blockchain art nor crypto art. “I would simply call it digital art, or digital design, that’s been tokenized in order to allow it to be bought and sold,” she explains.

Profile picture projects (PFPs) like Bored Ape Yacht Club mostly belong in the digital design category, and my issue with them is not that they’re repetitive, or even formulaic. Mark Rothko painted the same window-like abstractions in different colors and configurations for over twenty years. Warhol proudly manufactured his silk-screen celebrity paintings at an industrial scale with as little effort as possible — thus the name of his headquarters, the Factory. But unlike PFPs, the work of Rothko and Warhol rewards contemplation. For Rothko, the color field format was his way of inducing a state of transcendent self-examination, since the paintings resist interpretation in a way that diverts viewers’ awareness back to themselves. Warhol, meanwhile, applied industrial logic to fine art in a way that made people completely reconsider their position on what makes an object valuable or beautiful.

What makes CryptoPunk #5822 special? Not its visceral presence, nor its clever meta-commentary, but the fact that it belongs to the rarest batch in a collection of 10,000 NFTs. CryptoPunks play on nostalgia for low-bit graphics and, like many other PFPs, on gamers’ fondness for customizing characters. But making sense of a work of art requires that you look closely and try to figure out what you like, what you don’t like, and what stories it might be trying to tell you. Distinguishing one CryptoPunk or Bored Ape from another asks nothing of you; it can be done at a glance, in passing, without ever stopping to ask how it makes you feel. It provides the illusion of discernment without actually asking you to discern, in any real way, who you are and what matters to you.

There are still plenty of NFTs that do scratch my itch, even just perusing the list of bestsellers. Mad Dog Jones’ short video Replicator, which sold $4.1 million at a Phillips auction in April of 2021, is indicative of an NFT trend I call the “mood piece”: a scene that’s static but for a handful of animated elements. These animations tend to be unintrusive and relaxing—think of the Lofi Girl with the headphones on studying at her desk. On paper, the scene depicted in Replicator couldn’t be more nondescript: a copy machine in a high-rise office after hours blinks to life and starts doing its thing, then turns off again. But the neo-noir shadows and the glowstick hues cast by the office equipment create an ambiance that’s interesting for how inscrutable it is: a little cozy, a little sinister, like the placid scene is hiding a secret. Meanwhile, the copy machine — this dinosaur beeping its way towards obsolescence — is working late, unloved; it appears to gaze longingly out the window to contemplate the countless other lives it could have lived. This is a piece about alienation, nostalgia — and ultimately, death.

It’s interesting to note that the work also has a conceptual element, which is that the NFT self-generates unique variations of itself, mimicking the copy machine in a way. While I’m not fully convinced that it works (how can the artist assure that randomized variations even produce the desired effect?), it’s an interesting use of the technological function.

Pak’s NFT The Pixel, which sold for $1.36 million, builds on a time-honored tradition in conceptual art, which is to take something most people wouldn’t consider art and call it art. (You might call this trolling.) In this case, the something is a single gray pixel, minted as an NFT and put up for sale. What I like about The Pixel is its continuity with the great monochrome rectangles of art history, starting in 1913 with Black Square by Kazimir Malevich (sometimes called the “zero point of painting”); going up to the post-war period, when Yves Klein painted with his trademark ultramarine blue; and continuing to the minimalist Robert Ryman, whose white-on-white paintings eliminated color and depth of field to focus purely on texture and light. The funny thing is that, even 110 years after Melovich’s Black Square, passing off a monochrome rectangle as art is still a great way to cause a scandal. “The Pixel” is also provocative insofar as it’s extremely difficult to display, since one pixel is so tiny as to be barely visible. If you blow it up to visible size then it’s no longer a pixel, which invalidates the whole conceit.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/23610477/Screen_Shot_2022_06_06_at_1.11.39_PM.png)

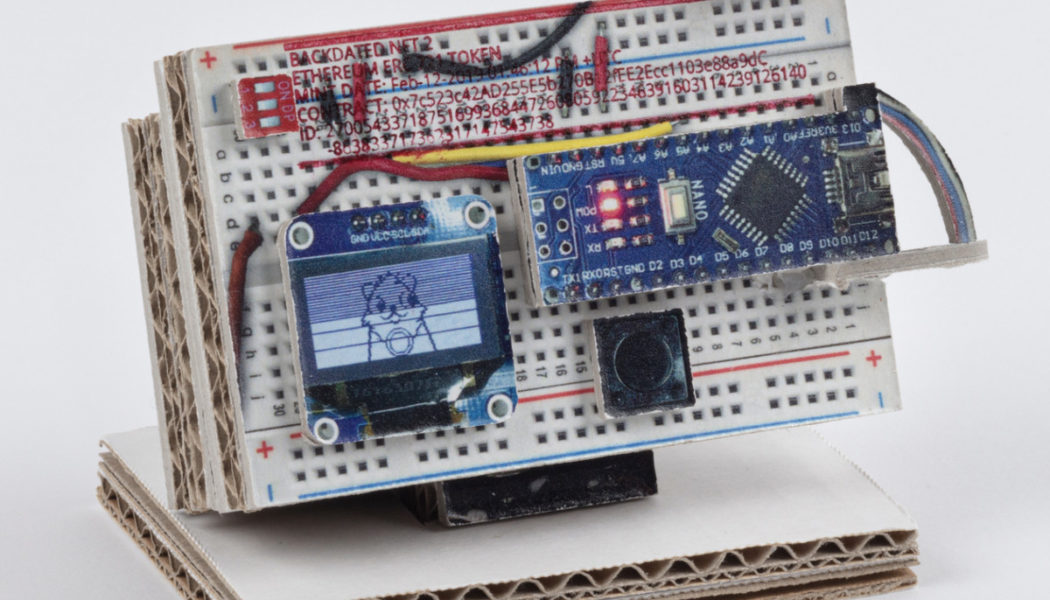

There are also more provocative specimens of what Tina Rivers Ryan deems blockchain art. Berlin-based contemporary artist Simon Denny, who represented his native New Zealand at the Venice Biennale in 2015, was one of the first established artists to speculate on the technology’s social ramifications. His project Backdated NFT/ Cryptokitty Display Hardware Wallet Replica (Celestial Cyber Dimension) challenges a fundamental tenet of crypto culture, which is that tokenization of a given asset certifies it, in perpetuity, as one-of-a-kind and unchangeable. The problem is that the digital image or video in question is usually too big to be stored on the blockchain, so the token points to a URL where the file is stored on the open web. “This means the digital assets that a blockchain entry points to can be changeable,” Denny told the magazine Flash Art in January of 2022. “For instance, you can stick a different image in the URL that hosts the original image. So, I did exactly that.” By purchasing older tokens and making them point to different media, a process he calls “hijacking,” he revealed the limits of the permanence that is supposed to distinguish blockchain from other forms of archiving.

These three examples couldn’t be more disparate in terms of genre, but in their own way, they each invite viewers to contemplate a mystery. What makes this sterile white-collar scene seem so tragic? Should a pixel that you can’t even see qualify as a work of art? Will our data ever truly be permanent? Art doesn’t have to be high brow or hard to grasp in order to be worthwhile, but it should at least make you reconsider something you thought you knew, if only a sunrise or a field of flowers. And when the collectible PFPs go the way of the Beanie Baby, the long-standing movement of artists who use technology to make people think will still be here tinkering.