The great fascination enveloping folklore, Taylor Swift’s mossy, surprise eighth LP, lies not within the album’s steadfast execution but the attempt itself — that during a global crisis which has paralyzed entire nations, a pop monolith would venture to swerve from her honey-soaked Lover’s lane and rumble deep into the forest, fixated on sonic reinvention. Hell, Swift’s fans would’ve been satisfied with a simple music video for her 11-month-old synth-bop “Cruel Summer.” Instead, she’s written furiously in isolation, launching an organic rebellion far beyond the pseudo-defiance of Reputation (nine Max Martin co-writes don’t exactly scream disobedience) and churning out the quickest album turnaround of her career. For studio expertise, she tapped the National’s indie-rock svengali Aaron Dessner and comfy producer-pal Jack Antonoff, who together shepherded a kaleidoscopic stream of consciousness unlike anything remotely resembling Swift’s past work. “Bad Blood” now feels light-years away.

As Swift noted on Instagram Friday morning, folklore comprises songs of “fantasy, history and memory” — rarely is it obvious across the 63-minute project that Swift is singing from genuine personal experience. “My imagination ran wild,” she said.

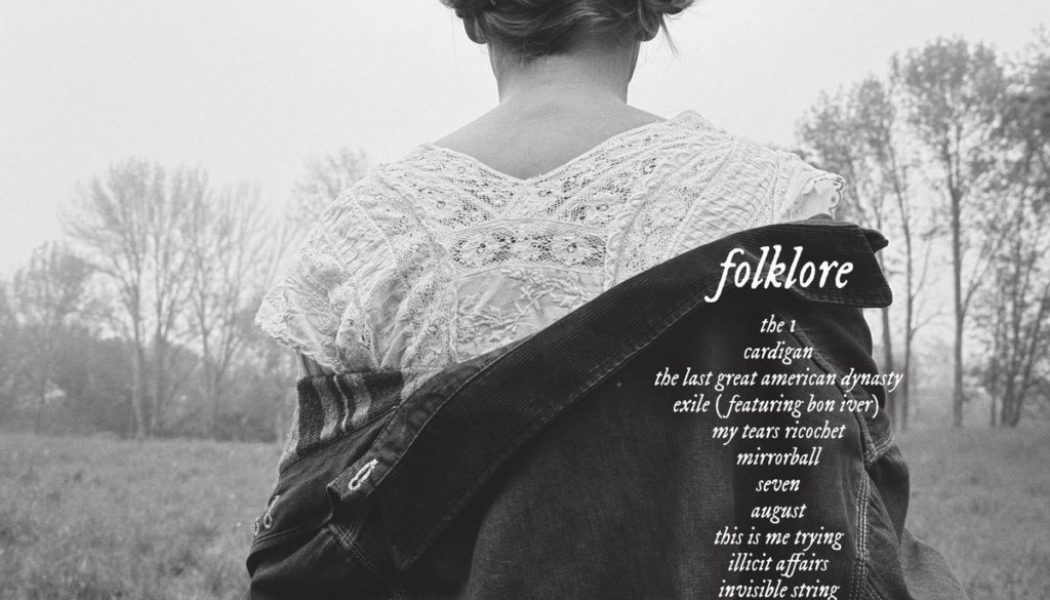

The mainstream deity wears well the role of a solemn storyteller, who’s more comfortable than ever weaving her tales without happy endings (and whose goth-inspired album cover looks like an Opeth throwback). Such an approach reminds of the darker tones found in Bruce Springsteen’s The River, the double-album that first saw the Boss wholly embrace the idea of telling other folks’ tales in the first-person — a formula that would guide him for decades. Swift may not be far behind on Highway 9.

But The River had “Hungry Heart,” the Boss’s first Top 10 single, while nothing from folklore suggests major victory on the Hot 100. The victory is in this album not caring. It floats much closer to the understated orbit of fellow Antonoff client Lana Del Rey, as well as the National’s most recent album, I Am Easy to Find, which welcomed a half-dozen stellar vocal performances from women into its fold. Swift declined to go for broke this time: No smothering roll-outs, no perceived crowdpleasers à la “ME!” or “Shake It Off,” which never seem to capture the essence of their respective albums. Though she couldn’t resist the urge to release eight different CD and vinyl deluxe editions.

“Cardigan,” the lead single (not that it matters), is a slow-burning, sonic cousin of “Wildest Dreams,” driven by tender piano and a clopping drum sample, accompanied by a fantastical self-directed music video. The song is one of three on the album to examine a love triangle, Swift revealed Friday morning, with each track — “cardigan,” the shimmery cut “august” and country-dusted “betty” — honing a different lover’s perspective. Though the story may very well extend further, considering “illicit affairs” is about just that and the break-up tune “my tears ricochet” is surely open to interpretation.

While Swift’s patented easter eggs are all well and good— comb through her ravenous subreddit to read fan theories about how credited songwriter William Bowery is likely her partner, Joe Alwyn — the album’s grandest highlight is “Exile,” her encompassing duet with Justin Vernon of Bon Iver, who opens the track with a rare untreated voice. “I think I’ve seen this film before, and I didn’t like the ending,” both wail as Dessner’s lush arrangement builds wistful piano into a sweeping, cinematic panorama. It’s immediately one of Swift’s most arresting collaborations to date, a worthy successor to her ethereal 2013 Hunger Games pairing, “Safe and Sound,” with the Civil Wars.

Throughout 16 tracks lasting over an hour, neither Dessner nor Antonoff dare to overstep the greater mission, though their markedly different percussive styles — Dessner being generally less linear, Antonoff more familiar — are easy tells in determining who worked on what. While Antonoff has developed a reputation as Swift’s prince of bombastic synth, his touch is notably lighter here, particularly on “august” and the traipsing cut “mirrorball,” which plays like the hopeful last dance of a junior prom.

Only once does Swift explore a ripped-from-the-headlines approach, on the later track “epiphany,” which captures a heartrending snapshot of the coronavirus pandemic: “Someone’s daughter, someone’s mother / Holds your hand through plastic now / ‘Doc, I think she’s crashing out.’” Depending on how much news you’ve read on a given day, it’s almost too much to take.

Elsewhere, “The last great american dynasty” is a meticulous history lesson on the Harkness family, of Standard Oil fame, who once lived in Swift’s Rhode Island mansion — someone did her research. And she drops the first F-bombs of her recording career, first on the biting “mad woman” — “Does she smile? Or does she mouth, ‘Fuck you forever’?” — wow — and again in the refrain of “betty”: “But if I just showed up at your party / Would you have me? / Would you want me?/ Would you tell me to go fuck myself?”

While the album tends to lull around its middle, folklore is far less concerned with its individual tracks than the greater, twisting conversation — the sort of hours-long, sanity-affirming chats that have become vital over these last four months. One musing bleeds into the next; sonic themes maintain a brilliantly downcast cohesion, like smooth obsidian glass. It’s a record born of necessity, a testament to her deep need to make music, even when it makes no sense to do so. She’s become a consummate songstress, even if she still feels underestimated, as she quips on “Cardigan”: “When you are young, they assume you know nothing.” She’s been proving otherwise since signing her first record deal at 15, half her life ago.