The U.K’s ‘lad mag’ culture meant that teenagers in the early 2000s had access to a startlingly adult education. From the top shelf of corner stores loomed titles like Nuts, Zoo, Loaded, and Max Power, which combined rudimentary soft pornography with a fetishized idea of young masculinity: one that centered around the twin pillars of topless girls and modified cars.

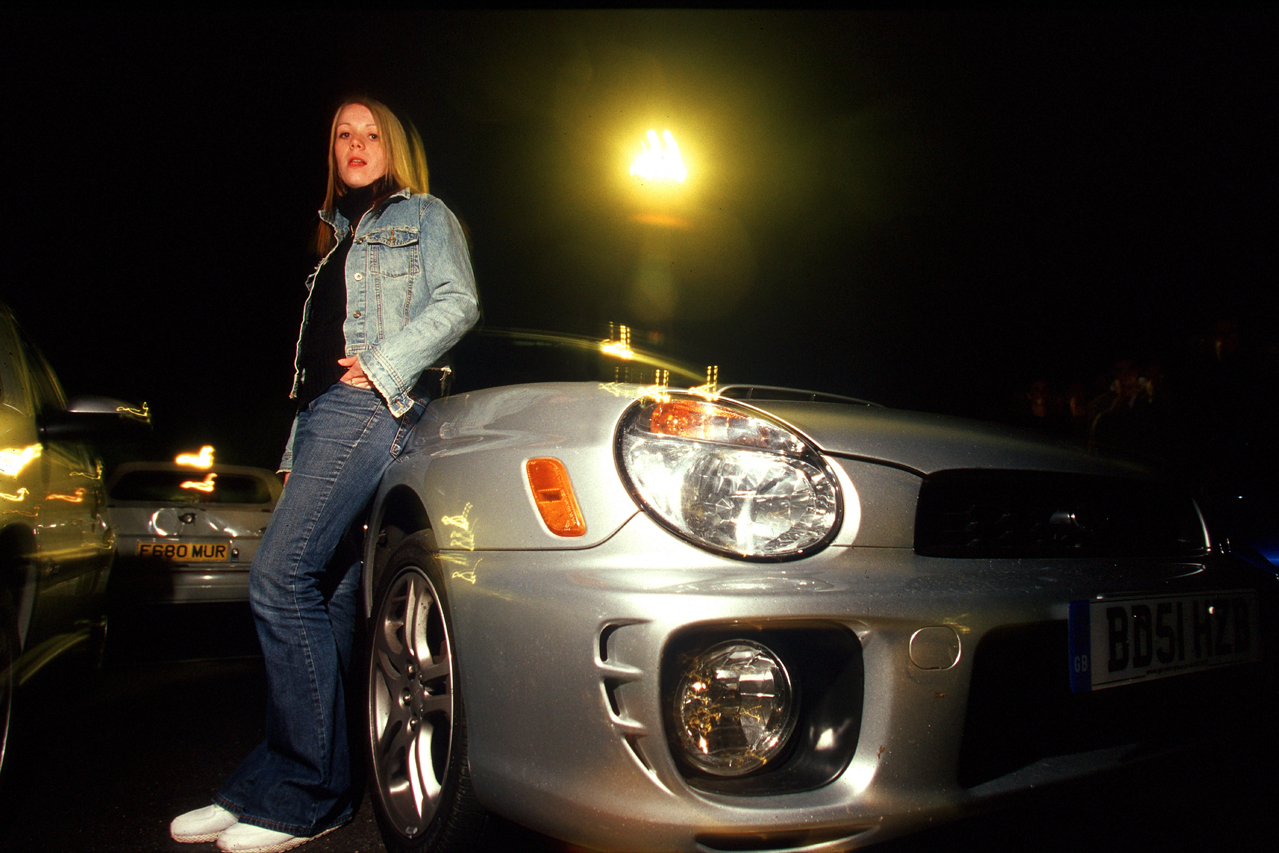

At their height, these publications were a cornerstone of British adolescence. The glossy pages were hidden from conservative parents, and instead were ogled over between friends in the back of someone’s first car – one which was complete with go-faster stripes and an oversized exhaust, in an eager, if misdirected, attempt to impress girls. They both documented and inspired a short-lived, but vastly influential subculture of young automotive fanatics.

20 years ago, the modified car scene – and those within it, who were branded as “Boy Racers” by sensationalist tabloid media – was rife, frivolous, and hedonistic. But it was also a place for people of all ages to come together over a shared passion for cars.

The scene and everything that came with it – plumes of tire smoke, bass thumping into the early hours, modified cars decorating your local industrial park – was endorphin-inducing for the crowd that called this their chosen family.

“One of my earliest memories is my brother’s friend’s Seat Ibiza – it had smoked lights at the back,” recalls John Joseph Holt, a magazine editor and former racer. “They were going to a nightclub and asked if I wanted to jump in. I couldn’t believe it: I sat in the back of this car, a Nicky Blackmarket mix blared through the sub in the back seat, reverberating through my body, as we hurtled through. When you’re that age, there’s nothing more adrenaline-fuelled.”

Remember: this was a pre-Instagram and TikTok era, when teenagers had little else to do to escape their parent’s watchful eyes. “In the night, when the headlights are on, the bodywork gleams, the smell of petrol and the smoke of tires, the injection of drum‘n’bass as someone opens their car door… I get goosebumps now even thinking about what it was like,” Holt says.

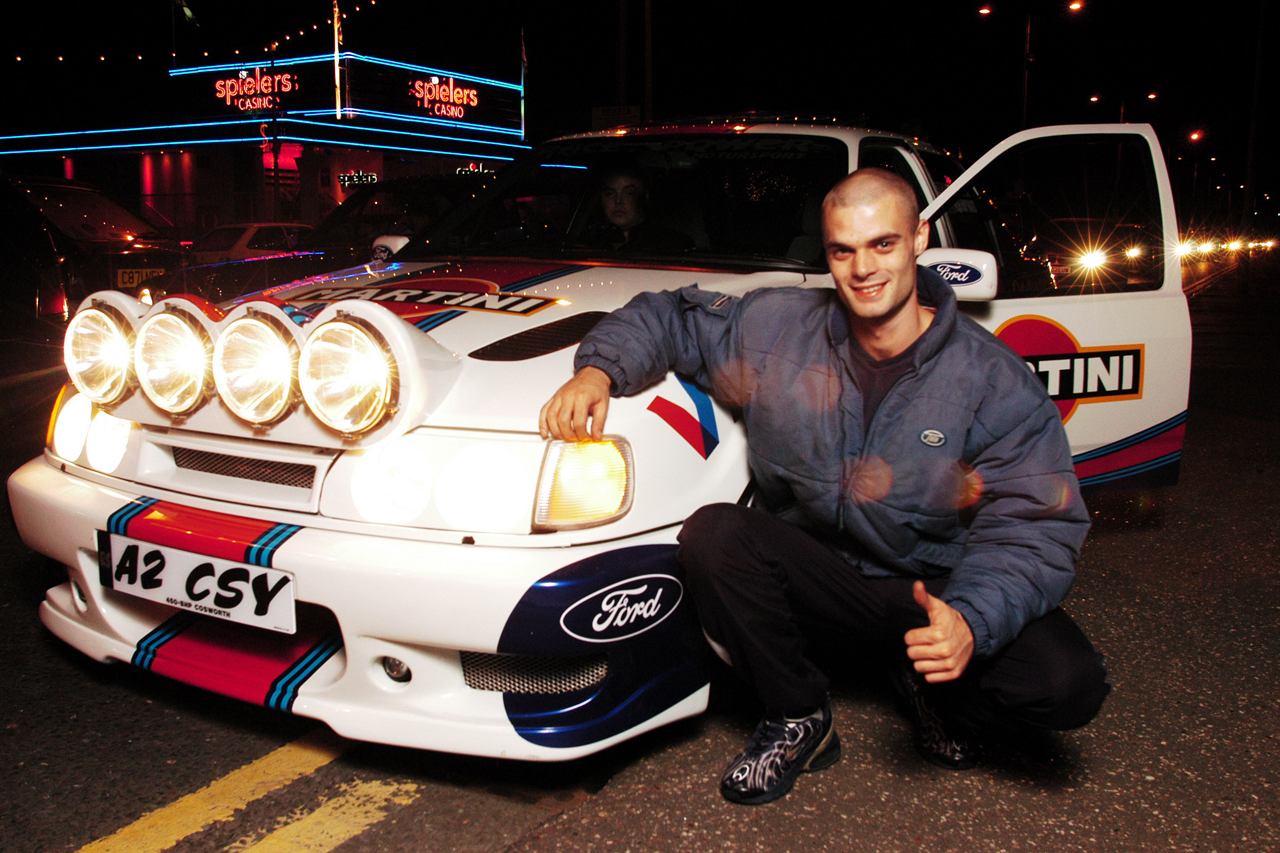

In the early 2000s, cult magazines and early incarnations of the Fast & Furious franchise spurred a new generation of high-octane enthusiasts. The automotive world – which had previously seemed reserved for middle-aged men – became simultaneously aspirational and subversive.

It exploded, particularly, in England’s Home Counties; semi-rural, suburban areas set just outside of London, including Essex, Kent, and Hertfordshire. “There’s a working-class culture that comes from these areas — places such as Essex, where there’s a lot of aspiration,” explains Jamie Brett, a car tuning fanatic and now the creative projects manager for the Museum of Youth Culture.

“The peacocking element of it all peaked in the South,” he adds. “It was an outlandish, cartoonish period of time. We always say at the museum that it was the scene, styles, and sounds that make youth culture, but it’s also what you drive. It was just as important as music and clothing.”

“You’d sit with the boys on the bonnet, listening to them talking about their engines: they might as well be talking in a different language… they’re poets, but they wouldn’t know it.”

Bringing this all together were privately-hosted events, colloquially known as cruises. Hundreds of teenagers would assemble on the motorway, before finding a spot to line up their cars: a remote suburb, perhaps, or the Southend seafront.

Holt spent many nights attending cruises with his friends. “It was a place to congregate, to share ideas,” he remembers. “You’d sit with the boys on the bonnet, listening to them talking about their engines: they might as well be talking in a different language. I didn’t know what they were talking about, but it was fascinating when you hear them talk – they were poets, but they wouldn’t have known it.”

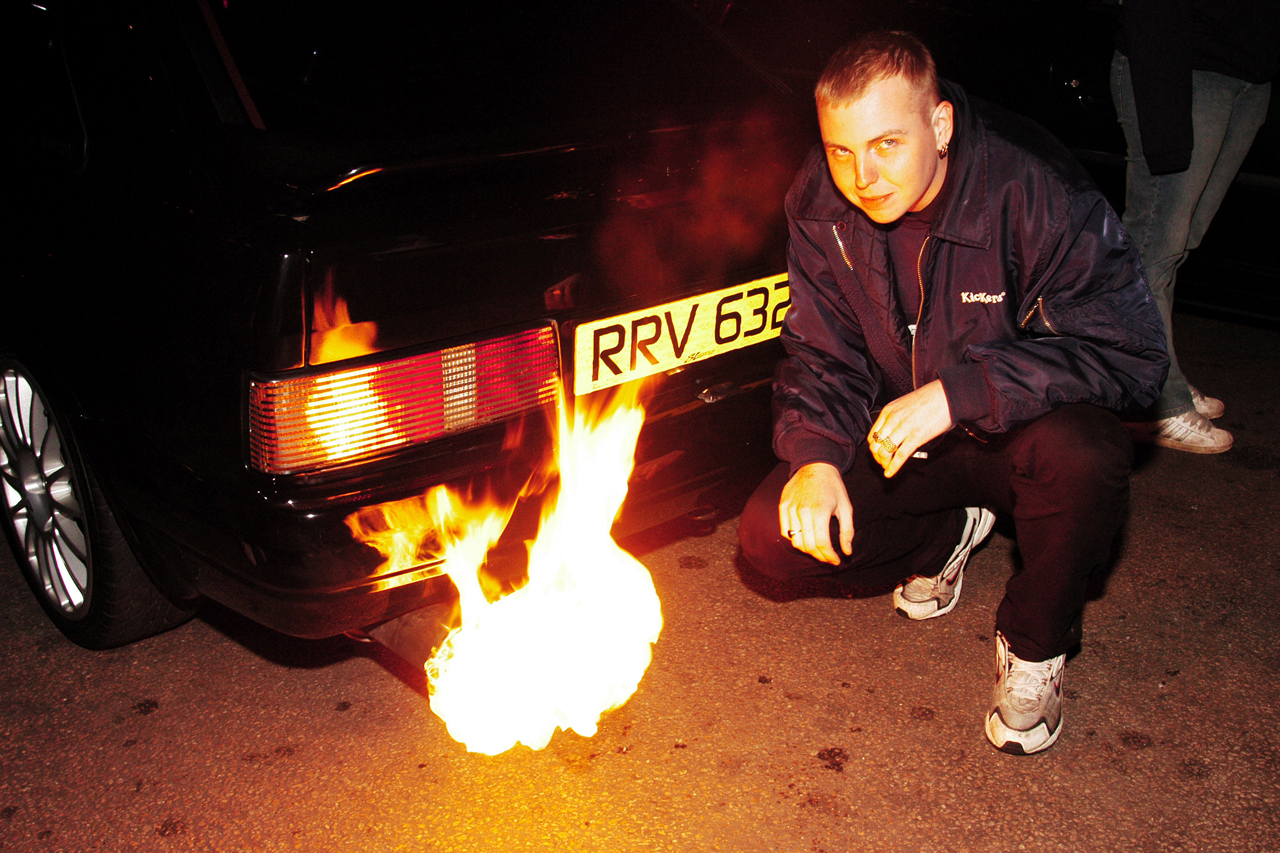

The problem was that, at such a young age, drivers seldom had the ability to control the cars they had so finely tuned. As Holt remembers, “you felt indestructible and untouchable when you were younger, but the sound of crunching metal would put you in your place.” Coupled with the noise of roaring engines, the perceived risk to pedestrians, and the occasional collision, the ‘boy racer’ culture soon became a byword for anti-social behavior, which often left its teenage drivers in high-risk situations.

Dan Anslow, an ex-staffer of Max Power and the co-founder of the online community MAXERS, concurs. “Sometimes you’d walk away at the end of the night and there’d be litter, damage to the tarmac, some cars might be stolen and set on fire – it was all getting a bit Wild West. I understand how people could get pissed off.”

It’s unsurprising, then, that the community was demonized and vilified by the press, and was largely chased out of youth culture. 20 years on from its heyday, the scene is a shadow of its former self. In a world saturated with electric cars and manufacturer restrictions, cars today are harder to modify and – arguably – less interesting.

Those with fast Fords in the 2000s grew up to own Porsches that they take to ‘Cars and Coffee’ meets in local villages, while today’s teenagers are largely priced out of the automotive industry.

And yet, there are signs of a revival. Second-hand cars are also rising in popularity, as a new generation are seeking something visceral: a tangible experience only found with cars that make a clunk when the door closes. “Just like there’s a revival in youth subcultures, people are also looking back at vehicles. People want to buy a piece of their past,” says Brett.

And as nostalgia for the perceived freedom of the early-00s reaches its zenith, modified car culture has begun to feel appealing all over again. “The U.K. is in a state of disarray at the moment. Growing up in the ‘90s and 2000s, you didn’t appreciate how special it was,” says Holt. “You look back at the ‘60s and ‘70s, how exciting those eras were, and you don’t appreciate your era. But looking back, there was so much to be proud of. It’s inherently British; we adopted these cars and made them our own. We made a scene out of it.”

A special thank you to the Museum of Youth Culture (and the photographers) for sharing its archive with HYPEBEAST. You can find the MOYC on Instagram, and you can submit your own images to its archives online.