The day after New Year’s, the CEOs of the two biggest wireless carriers in America sent a very angry letter to Pete Buttigieg. The companies had been working for years to launch a new portion of their 5G networks, a launch that had been scheduled for December and then unexpectedly pushed back due to vague air safety concerns. Now, the Department of Transportation was asking for more time, just days before the scheduled launch.

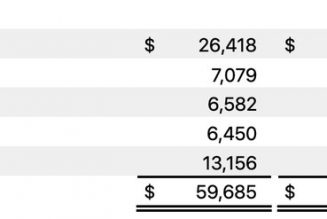

“In addition to the tens of billions of dollars we paid to the U.S. Government for the spectrum and the additional billions of dollars we paid to the satellite companies to enable the December 2021 availability of the spectrum,” the CEOs wrote, “we have paid billions of dollars more to purchase the necessary equipment and lease space on towers. Thousands of our employees have worked non-stop for months to prepare our networks to utilize this spectrum.”

As of yesterday, the spectrum launch is back on — pushed first to January 5th, then two weeks later to January 19th — but it’s been an unusually rocky road for US wireless carriers, bouncing between regulators at the Federal Communications Commission (FCC), the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA), and increasingly vocal unions for pilots and flight attendants. At the heart of all of it is a nagging fear that the latest round of 5G spectrum will pose a threat to commercial airlines and their passengers. But it’s such a complicated issue that it’s best to unpack it one piece at a time.

Carriers and airlines are fighting over a particular chunk of spectrum from 3.7 to roughly 4.0 GHz – primarily used by AT&T and Verizon, sometimes referred to as C-band. (T-Mobile is using a separate mid-band patch at 2.2GHz, so it is largely sitting this fight out.)

This isn’t all the 5G spectrum, but it’s some of the best parts. The most powerful thing about 5G is the ability to transmit huge volumes of data over these mid-band frequencies, and this spectrum is the main way AT&T and Verizon are planning to do it.

“There’s a reason they paid $65 billion for this spectrum,” says Public Knowledge’s Harold Feld, who wrote about the issue at length in November. “They don’t have sufficient mid-band spectrum without it.”

Crucially, we’re at the last step in a very long process. If you bought a 5G-capable phone, you already own a device that can send and receive on those wavelengths, and there are already cell towers that can manage those signals. All that’s left is to turn them on, at which point the C-band airwaves will get a whole lot busier.

Airlines are worried those busier C-band airwaves will interfere with their equipment. In particular, they’re worried about radar altimeters — a device that bounces radio waves off the ground to give extremely precise altitude readings. It’s a crucial device for landings, particularly in conditions with limited visibility, and relies on having an empty patch of spectrum to work in. Faulty altimeter readings can also trigger automated responses from autopilot systems, as in a 2009 Turkish Airlines crash that left nine dead.

As a result, the entire industry is deeply uncomfortable with anything that might interfere with altimeters. As an airline pilot’s association put it in a 2018 filing to the FCC, “the public interest would not be served if tens of thousands of existing aircraft worldwide were inadvertently no longer provided the safety protection enabled by radio altimetry equipment due to interference from adjacent bands.”

This is the 65-billion-dollar question! As one tech trade group is fond of pointing out, this spectrum has already been rolled out in 40 different countries without any resulting altimeter failures, although some of those countries are operating it at lower power levels. But the FCC has spent three years going back and forth with various airline groups on this question, and a lot of them are still worried.

The FCC has a number of measures in place to prevent interference. There’s a full 220 MHz of clearance between the spectrum used by the radio altimeters (which starts at 4.2GHz) and the new 5G spectrum (which ends at 3980MHz). The FCC even carved an extra 20MHz from the 5G holdings when this issue was raised in 2018 to give aircraft extra space. There are also several restrictions on how 5G towers should be configured near airports to avoid flooding the airwaves in areas where planes are landing. In a modern plane with a modern radar altimeter, it should be easy to avoid interference.

The problem is, not every aircraft has a modern radar altimeter. Both sides acknowledge that at least some altimeters are affected by signals from outside the intended spectrum bands. To be clear, this is a malfunction — but it’s a malfunction that wouldn’t have been relevant before C-band came online. As things stand now, it’s not clear how many faulty altimeters are out there or how they’ll respond to a flood of 5G traffic. And because even a single interference-related crash would be tragic, it’s hard for airlines to feel secure about the rollout.

For the FCC and wireless industry, the ideal solution would be for the FAA to launch some kind of industry-wide effort to find and replace faulty altimeters. In fact, they would have liked it to launch in 2019, when the rulemaking for the spectrum first began. But that didn’t happen, and it’s unlikely to happen in the next two weeks.

Verizon and AT&T are coming up against a deadline of their own. 5G-capable phones have been available in the US for two years now, and carriers are expecting a flood of new customers as holiday devices come online. Both networks have some 5G capacity already in place, but without the C-band spectrum, their networks are increasingly stretched thin. In February, AT&T plans to shut down its 3G network entirely as part of the transition to 5G. All that traffic has to go somewhere — and without new spectrum, the result will be spotty, inconsistent service. At the same time, T-Mobile is skating by without any of these problems and has been aggressively marketing its 5G network to draw away customers.

Another two weeks isn’t too big of a deal for the carriers, which is part of why they were so eager to accept the deal, but further delays could start to do serious damage to their business plans. With each passing month, the drag on the network gets a little more severe, and the damage from a $65 billion dead asset gets a little harder for shareholders to ignore.

“The thing the carriers were really worried about was, how long is this going to go on?” Feld says. “You have this combination of surging demand and concern that you won’t ever be able to use the spectrum.”

One way or another, AT&T and Verizon are planning to switch on their networks on January 19th, and the airlines and pilots will be on high alert for the first sign of any interference. The FAA has promised to use the extra two weeks to craft an airworthiness directive for any planes that might be affected, which will stave off the most severe shutdowns or delays. Given the tight timeframe and mounting pressure, it’s very likely the best the agency can do.

But for observers like Feld, the most frustrating thing is how much time agencies have already wasted without addressing the issue. “This shouldn’t have been a problem. Since the FCC started this rulemaking in 2019, we’ve known this was coming. The steps that are necessary to address this are fairly straightforward,” he told me. “It’s unfathomable.”