This article originally appeared in the March 1991 issue of SPIN.

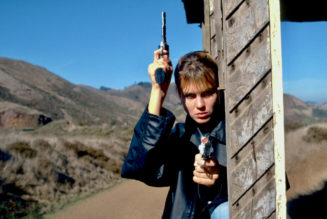

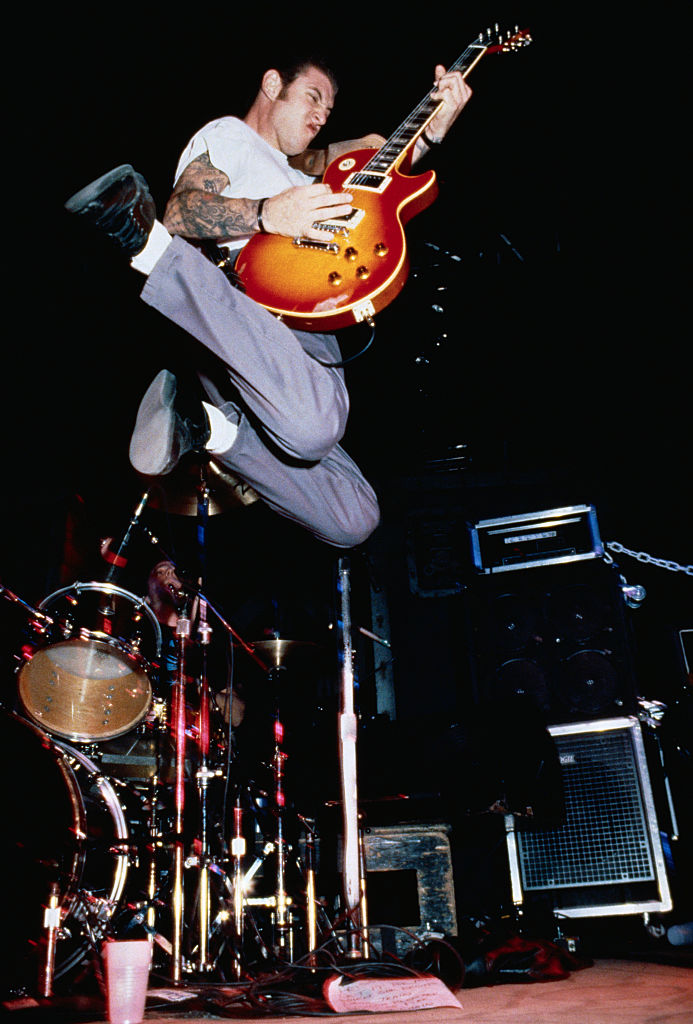

It was like a scene out of Penelope Spheeris’s punk documentary, The Decline of Western Civilization. Social Distortion pounded away onstage while broken glass and a sheen of blood covered the dance floor. Big goony bouncers grabbed kids by their mohawks, or in the case of skinheads, their necks, and chucked them out the door.

While general slam-dancing mayhem erupted near the stage, bassist John Maurer paced back and forth with a shiner, not due to any offstage rumbling, as most of the audience thought, but because earlier that day he had gone to San Francisco’s notorious body-piercing palace, the Gauntlet, to get his belly button done. As he sat on the table informing the mistress of ceremonies that he wanted the flesh on the bottom pierced, she told him it would hurt a lot less if he had it done on the top. No, John knew what he wanted and was determined to get it. As she turned hack to the table after retrieving her tools, he took one look at the tray filled with needles and antiseptic and fainted dead away, falling off his perch and hitting the floor hard enough to blacken his eye, his bad-boy image put to shame.

But this audience didn’t know that, and as the band launched into “Sick Boys,” a tune off its latest album, a chair was hurled halfway across the club…. Some things never change.

Since Social Distortion’s birth in 1979 in Southern California, guitarist, singer, and founder Mike Ness has seen a bad heroin habit come and go, the inside of a few jail cells, and a hardcore punk reputation he can’t seem to shake.

“Just ’cause we came out of the Orange County punk scene, that doesn’t mean that’s what we play till we die,” says Ness. “We were just learning then, but even now we can’t seem to lose the label.”

Even in the early days it was obvious there was more to Social Distortion than most of the other two-chord slam outfits on the scene. It wasn’t necessarily that they could play that well—but there was an underlying bluesy-rock energy that only needed some time to surface. And when they sang their 1983 anthem “Mommy’s Little Monster” the words weren’t so much about “fuck the world, I want to get off,” like a lot of the other 30-second sing-alongs, as “check it out, this generation is getting screwed.” “Most of the bands that came out of that scene aren’t around any more,” says guitarist Dennis Danell, who has been with the band since the early ’80s.

“Either that, or they’re doing lame-assed, meaningless stuff,” adds Ness. “I see some of those guys every once in a while, but there’s not much to say. A lot has changed. Back then the kind of girls I used to hang out with were junkies and lowlifes. Now the ones we hang out with have jobs, money, some direction in life.

“So much has happened in five years in all of our lives. For me, especially, it seems almost like I’ve started life all over. I feel totally grateful.”

Orange County, just south of Los Angeles, is one of the most conservative and wealthiest counties in America. With rows of sprawling houses inhabited by upper-income families, it’s easy to see why this area earned the nickname “Reagan County.” In the early ’80s, this idyllic spot spawned one of the most violent and self-destructive punk scenes to come out of California. The Germs, TSOL, and the Circle Jerks taught Orange County kids how to slam—but the aftermath, in most cases, was crash and burn.

To some people it seemed that, while their English counterparts had dole lines (or at least art school classes) to contend with, the Orange County punks didn’t have anything more than the smog to worry about. But the general feeling of this thriving scene was that wealth was a facade, a way to anesthetize you from thinking, and on any night of the week you could go to the Cuckoo’s Nest in Costa Mesa, the club where this network of bands played, and spit in the face of adult convention. There was Flipside, the magazine that clued in all O.C. punks worth their weight in safety pins to the scene. And the parties—that took place in houses abandoned by parents vacationing in Europe—where, more than likely, some form of physical disintegration would take place. Mike Ness knew a lot about this. He was well on his way to developing a bad heroin habit and would often be seen in the parking lot with a liquor bottle in his hand. “I was very pissed off back then,” says Ness. So pissed that at the band’s first live gig he got carted off to jail for spitting in the face of a plain-clothes cop.

When Ness’s heroin habit hit rock bottom in ’85 and the band started to flounder, it became increasingly clear that unless he got it together he would not live to tell. He went into a drug recovery program and came out with music churning through his body instead of chemicals. “I was always very single-minded about what I wanted to do with the band,” he says. “I mean I figured it was pretty much my destiny, whether it was success or failure. I was just supposed to be a musician. Back then there really wasn’t any alternative. Even though now there are other things I could do for a living, it’s like, ‘Why would l?’”

In 1988 the LP Prison Bound was released with Danell on guitar, Maurer on bass, and Christopher Reece on drums. The album showed Ness wearing his hardships on his sleeve. “Prison Bound was immediately after I got clean,” he says. “Things are a lot clearer to us now as far as what direction we want to head in and what our primary influences are. Whereas back then we were just coming out of a fog, the first record in five years, we were like, ‘Hello, what’s out there?’”

Social Distortion went on the road, building up a steady following that included fans from the old days. Ness says, “We did a lot of live shows and we tried a couple of projects that didn’t come out exactly as we’d have liked them to, so we chose not to release them, and it was an expensive lesson for us.”

“We had gotten calls from guys at some independent labels and they were talking the language,” says Danell. “At the time we didn’t know anything about the industry and they’re telling us, ‘We’ll meet you down at the Harley Davidson shop and buy you guys four new Harleys.’ And I had called my manager going, ‘I want a bike so fucking bad.’ And he goes, ‘Nope, don’t settle for the immediate gratification.’”

“Sometimes you got to wait, and it’s hard,” adds Ness.

“We would have been looking good for about six months until the bikes started breaking down,” Danell continues. “And then we would have had to sell them to pay the rent, and three years down the line we’d have no motorcycles and still have to do three more albums.”

The patience paid off. In 1990, 11 years after the band’s first gig, Social Distortion entered the studio and recorded its first major-label release for Epic Records and then went back on the road. Everywhere the band went fans were waiting, some who obviously thought the slam pit days were still in action, but others who came for the straight-ahead, sweaty rock’n’roll.

“I think we have a good cult following,” says Ness. “Like we don’t see them for a few years, then they show up to say, ‘Hi’ and they’re still crazy.”

“We’re not inaccessible to people,” says Danell. “I like to make new friends. I’m not going to give anyone an attitude that wants to come up to me to ask me questions about the band or myself or whatever.”

“We like to have fun,” adds Ness. “There are times when you want to be alone, but none of us are recluses. You have to have people around to have fun.”

“Yeah,” says Danell, laughing. “No fun hanging out just with yourself.”

After finishing up a North American tour with Neil Young, the Social Distortion crew will release a new album, after which they’ll be off to Europe and Japan. Sometime during this busy schedule, Ness has to return home to Costa Mesa so he can drop off all the collectibles he’s picked up on the road. It’s his hobby. In every town there are at least a couple of antique and thrift stores waiting to be pillaged. In one instance, he found a full-scale deer’s head that he couldn’t live without, so he bought it and enshrined it on the back bench of the bus, taking up an entire seat. And there it stayed with no one allowed to get near it or disturb it. Other faves in the Ness collection: antique dolls, figurines, and ceramic lamps.

“Maybe someday I’ll open a showroom and put everything on display,” offers Ness.

“I’d like to have a shop where we could work on our cars,” says Danell. “And do all kinds of, you know, boy type of things.”

“Where we can rehearse, too,” adds Ness. “And all the people we know cross-country with cool cars and shit can come and visit.”

The band has come a long way from the days of sleeping on floors and fighting for its pay at the end of the set. “We’re at the point now where we can actually think about things other than how to make ends meet,” says Ness.

“Because we’ve had our share of shit jobs,” adds Maurer. “When we weren’t gigging and there were bills to pay I learned a trade.”

“Yeah. We’ve paid our dues as far as that goes,” Ness says. “We know what it’s like to be blue-collar workers.”