When actor, novelist and musician David Duchovny was 10 years old, he failed his Grace Church School choir audition in front of a bunch of his friends. Even worse, they’d assured him that nobody gets rejected.

As Duchovny tells it, he misunderstood the instruction. When he was told to sing the note “after” the one the choirmaster played on the piano, Duchovny interpreted “after” to mean the next note in the scale and sang a higher note instead of matching what was played — a mistake he repeated several times in a row. Although he didn’t make it into the choir, his audition was impactful, nonetheless, as evidenced by the baffled looks on the faces of those who witnessed it.

Even now, five decades later, Duchovny winces as he relays the anecdote. “I went home, and I was just mortified,” he says. “I was devastated and humiliated.” Dressed casually in a black t-shirt and black jeans, Duchovny is sitting at a Burbank studio where he was just interviewed for a podcast to promote Gestureland, his latest record and third release since 2015.

Duchovny conceived the album’s title at the height of the pandemic, when everyone was stuck at home and forced to connect remotely amid a chaotic and politically charged era. “I was yearning for a more substantive conversation instead of trading signs,” he says. “We’d been signaling to each other through screens…wearing t-shirts and hats, all these things that affiliate you or get you in trouble, and I started to think, ‘I’m lost. I’m swimming in a sea of gestures.’”

Musically, Gestureland fuses myriad influences, from Neil Young to Neutral Milk Hotel to The Smiths, into a timeless and melodic collection of mid-tempo tunes, ballads and rockers. Orchestrated with strings and horns, the 12 songs are at turns gritty, stark, and dreamy. It’s a rich and textured sonic tapestry, with Duchovny’s vocals sitting high in the mix. His introspective lyrics beautifully express the profundity of human connection, making Gestureland as intimate as it is existential.

Duchovny is eager to perform Gestureland live and says he’d like to do a cross-country tour of America, something he’s never done. But for now, the pandemic’s put show plans on hold. Over the last several years, however, he’s played select American cities and headlined legendary rock venues including The Roxy and The Stone Pony. What’s more, he drew 3,500 attendees to his overseas concerts, with a group of particularly zealous fans traveling across Europe to catch each gig.

Still, Duchovny’s music may come as a surprise to those who know the two-time Golden Globe winner by his portrayals of paranormal-obsessed FBI special agent Fox Mulder on The X-Files and the charming, complicated novelist Hank Moody on Californication.

But no one’s more surprised by his music than Duchovny. “I still have wonder and awe that I get to make songs because it was never anything I thought about,” he says. “But I always loved music so much.”

An avid music fan since childhood, Duchovny is as knowledgeable about it as he is enthusiastic. He’s currently engrossed in The Magic Years: Scenes from a Rock-and-Roll Life, a memoir written by former Bob Dylan and The Band road manager Jonathan Taplin.

Throughout the afternoon, Duchovny sings parts of various songs aloud, from Robbie Robertson’s “Broken Arrow” to Blue Oyster Cult’s “Shooting Shark.” He quotes song lyrics (Elton John’s “Come Down in Time” and Warren Zevon’s “Desperados Under the Eaves”) and references numerous artists spanning various genres and eras — Laura Nyro, Sly and the Family Stone, Alice In Chains, Lynyrd Skynyrd, Hayden, Sia, and Pine Grove. He beatboxes while tapping his fingers enthusiastically on the table in front of him when he mentions Timmy Thomas’s “Why Can’t We Live Together.”

He’s also swift with a quip or observation, whether it’s Hanson’s “MMMbop” (“That song was magic.”), Aimee Mann’s “You Stupid Thing” (“Deadly. You don’t want to break up with Aimee Mann or make her mad.”) or Stone Temple Pilots (“I love that band. They really got shit on from the critics, didn’t they?”). And he speaks earnestly about songs he finds particularly moving — Daniel Lanois’ “The Messenger,” Harry Chapin’s “Cats in the Cradle” (“As hokey as it is, I’m defenseless.”) and Bob Dylan’s “Blind Willie McTell” (“It’s the perfect lyric that ties unrelated historical sadness to personal sadness in a mystical non-linear way.”).

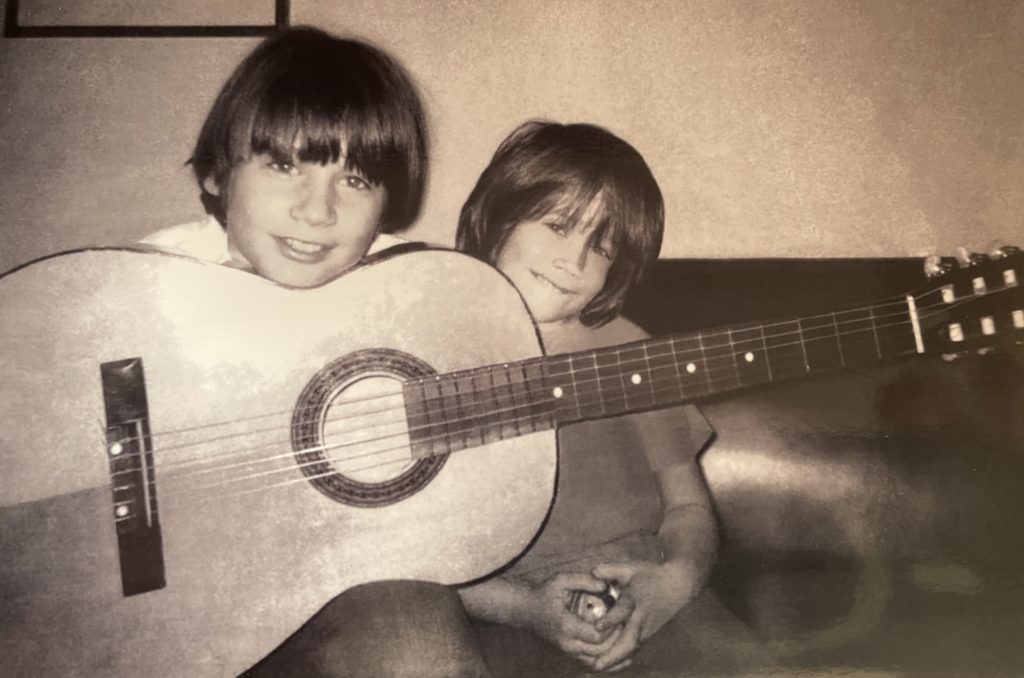

It seems inevitable that Duchovny’s lifelong passion for music ultimately led him to make his own. In fact, he might have started sooner were it not for a couple of uninspiring guitar lessons from a musical instrument shop owner when Duchovny was 10 years old.

“I guess the teacher wasn’t good or I wasn’t good,” he says. “My dad would take me into the store, and the guy would start the lesson, but behind the cash register, and then my dad would leave and the teacher would leave me there and say, ‘Practice that.’ It was unfortunate because it’s always those things that if you had a good teacher…”

Between that and his failed choir audition, Duchovny’s experiences at the age of 10 stopped him from returning to music for decades. It was 40-ish years before Duchovny picked up the instrument again, teaching himself to play chords before receiving weekly lessons on the Californication set after he suggested to the show’s creator, Tom Kapinos, that Hank Moody should play guitar.

Initially, Duchovny was content to play covers, looking up chords online. The Flaming Lips’ “Yoshimi Battles the Pink Robots, Pt. 1,” Tom Petty’s “Free Fallin’” and the Allman Brothers Band’s “Melissa” were among the first tunes he learned. However, when he started hearing original melodies in his head, he was keen to shape them into songs, which his musician friend, Keaton Simons, helped him save to his phone in Simons’ recording studio in his garage. That was as far as Duchovny’s recording aspirations went.

But after he performed his song “Stars” as a guest at one of Simons’ gigs, Brad Davidson (a music industry veteran who later became Duchovny’s music manager) encouraged Duchovny to make a record and introduced him to a talented group of musicians: Colin Lee (keys), Pat McCusker (guitar), Nathan Reich (guitar), Mitchell Stewart (bass), and Sebastian Modak (drums).

Initially, Duchovny’s band fleshed out his songs as Lee took the production reins (along with McCusker and Stewart co-producing), culminating with Duchovny’s debut record, 2015’s Hell or Highwater, which Rolling Stone called “a likable, lyrically tart, vaguely Wilco-ish debut album.” Duchovny and his band leaned into co-writing on their second LP, 2018’s Every Third Thought, but he says they finally hit their sweet spot with Gestureland (co-produced by Lee, McCusker and Stewart, with drummer/percussionist Davis Rowan replacing Modak and guitarist Keenan O’Meara replacing Reich).

“This one is really collaborative,” Duchovny says. “Not only that, but they’ve gotten more confident in imposing their soundscape on me, and I’ve gotten more articulate and confident in being able to describe what it is I want.”

He is less confident, however, when praised. In the face of the ubiquitous skepticism toward actors’ music pursuits, Duchovny has distinguished himself from the bulk of his thespian rocker counterparts, receiving positive reviews and comparisons to some of his favorite artists, like Tom Petty, Warren Zevon and Lou Reed. Still, he’s conflicted. “It makes me quite happy, and I also feel like a terrible imposter,” he says.

But Duchovny works diligently to develop his vocal chops, taking weekly voice lessons and maintaining a daily 25-minute warm-up regimen. However, he remains self-conscious. “It’s very personal,” he says. “Singing is so vulnerable, especially for me who’s not great. For me to sing, it’s very naked, and my singing is not super-expressive. I’m not belting shit. It’s not like [A Star is Born’s] ‘Shallow.’”

“But just me singing is something,“ he adds. “I don’t play it as safely as I used to, which is good. That’s something I got over later in life.”

At 61 years old, Duchovny easily looks a decade younger. He stays in shape with a combination of pilates, boxing, swimming, tennis and yoga. But beyond his later-in-life music career, Duchovny’s path has never been a straight line.

Born in summer of 1960, Duchovny grew up on New York’s Lower East Side in what he describes as a lower-middle class family. A middle child (older brother Daniel is a commercial director and younger sister Laurie is a schoolteacher), Duchovny says his personality was influenced by birth order. “I think you’re a mediator, a peacemaker and maybe not as spoiled,” he says. “The oldest was an only child for a while, and the youngest is the youngest. You get the reality earlier than other kids. I think it’s good.”

For the most part, Duchovny says he was a “good and gentle kid,” “very sensitive to others’ feelings” and “shy and quiet, especially around adults.” With a fondness for basketball, tennis and baseball, he dreamed of being an athlete when he grew up.

His Russian Jewish father, Amram (“Ami’), worked in public relations at the American Jewish Committee and, later, Brandeis University. In his heart, however, Amram was a writer like his father, Moshe, a playwright, novelist and journalist. In his downtime, he penned several political satire books, a Broadway play and, at 72 years old, a novel. He instilled the importance of books and reading in Duchovny.

Duchovny’s Scottish Lutheran mother, Margaret (a.k.a. “Meg”), was a second grade teacher and school administrator who, when raising Duchovny, stressed the importance of education — which was the pathway out of the poverty into which she’d been born.

“I’m impressed with my mom, looking back,” Duchovny says. “She was the first woman in her family to get a college education, probably one of the only people ever to leave her town (Whitehills), so it wasn’t easy for her.”

As a result, Duchovny says he was raised with a “life hurts” philosophy, which “makes me funny, but I probably have a cap on my ability to experience joy. I don’t go to 11 on that meter.”

Duchovny is also prone to depression. He’s not sure when it first started, although it may possibly have been when his world was shattered by his parents’ divorce when he was 11 years old. Their parting left a “formative rupture” that still affects him. “I think divorce can make you distrust the ground beneath your feet forever, and that may be the case for me,” he says. “When I experience a setback, I wake up with a crushing feeling in my chest and I feel like I’m in danger. And that could be coming from there.”

The divorce also marked the end of a close relationship with his father, who, when Duchovny was 14, moved to Boston for nine years, before settling in Paris where, in 2003, Duchovny hoped to impress him. At the time, Duchovny was preparing to film House of D, an independent movie he wrote and directed, shooting primarily in New York with three days on location in Paris.

“My father had not been present for my switch into show business,” Duchovny says. “I never really saw him once he moved to Paris. We exchanged letters, but we didn’t talk on the phone much. I just really wanted to show him I was a man, had a job and was like a [military] general on the set because I was the boss. I was creative. I was writing. I thought he’d be proud of me.”

Sadly, that moment never came to be. The elder Duchovny died of heart disease at 75 years old while the film was still in pre-production. For two weeks following his father’s death, a grief-stricken Duchovny listened repeatedly to Warren Zevon’s version of “Knockin’ on Heaven’s Door.” Zevon died two weeks after Duchovny’s father.

“It’s a sadness I carry,” says Duchovny. “I miss him, but, even more, I miss how we didn’t do it. I don’t get to have him. I’ll never get to have him. We didn’t come through for one another, and I don’t get another chance.”

However, Duchovny has always been close with his 91-year-old mother, who he describes as his “mama bear” growing up. “She was my greatest defender and my greatest advocate,” he says. “Her love was fierce in that way.”

When child psychologists assessed Duchovny as hyperactive at approximately five or six years old (“It seems so weird because it’s not my vibe, but I guess that’s what was coming out of me.”), his mother said, “Just because you can’t handle him, doesn’t mean there’s anything wrong with him.”

Duchovny pauses, choked up for a moment by his mother’s protectiveness, and says, “How fucking beautiful is that?”

But Duchovny, who always excelled at school, is nothing if not focused, explaining that somehow he got the lesson that he had to rein in his excess energy.

He attended Collegiate School (a private high school for boys) where, as athletic as he was heady, he was captain of both the baseball and basketball teams. He was also awarded the distinction of Head Boy, bestowed for extraordinary academic and athletic achievements.

Duchovny continued to play basketball and baseball in his first year at Princeton, where he completed his undergraduate degree in English literature. Next, he pursued his Ph.D. at Yale, where he was on track to become an English literature professor who wrote novels during the summer months. But while Duchovny was pursuing his doctorate, things changed course dramatically — literally.

At home on a summer break from Yale, he wanted to earn enough money to carry him through the next school year. As per a friend’s suggestion, Duchovny signed with a talent agency and immediately got work in commercials. When his agent said she would send him on theatrical auditions if he took acting classes, he signed up immediately, studying Method Acting under the tutelage of Marcia Haufrecht and the Meisner Technique with Robert Modica.

The now-84-year-old Haufrecht, an actress, filmmaker and artist who retired from teaching 10 years ago, remembers her former student fondly. Over the phone from New York, she recalls Duchovny as being “a very good-natured and generous person with a wonderful sense of humor.”

What’s more, his striking intelligence and thoughtfulness impressed Haufrecht, who says Duchovny was also noticeably reticent. “He didn’t take anything at face value. He had to think about it first,” she notes. “But then he’d jump in with four feet, so to speak. He goes 100 percent with whatever he does.”

Haufrecht was unfazed that Duchovny started acting at 26 years old, but it came as a shock to Duchovny’s friends and family, who thought he’d lost his scholastically oriented mind. To this day, his mother still asks Duchovny why he acts.

“People were saying, ‘What the fuck are you doing? Why are you doing that?’” Duchovny says. “I didn’t seem to be that needy person who needed to be looked at. I didn’t seem to be a person who was interested in money.”

Duchovny’s explanation was simple. He thought acting was fun. Ultimately, however, he discovered it served a much greater purpose, allowing him to delve deeply into his emotions, which was never his comfort zone.

“I needed to find my heart,” he says. “I needed to give voice to my feelings somehow. That was never anything that was encouraged from me in my life. I was raised to use my brain and my body — to think and play sports. I was dead set against feeling, and then I got into this space of acting where that’s what you’re supposed to do. That’s your job. That’s fantastic.”

Once it was clear to Duchovny that he preferred the excitement of life in front of the camera to a staid life in academia, he dropped out of Yale with an ABD (All But Dissertation). He moved to Los Angeles, where New Year’s Day, the first film in which he was cast (after appearing as a party guest in Working Girl), was opening in two theaters.

He was initially incredulous when the film was screened at the Directors Guild of America. “When I first saw myself on screen, I thought, ‘Oh my God, I’m an actor. That’s crazy.’ It’s an odd feeling to see yourself on screen like that.

“But I thought it could work. I didn’t look away,” he adds with a laugh. “I didn’t seem terribly uncomfortable or disappear like a black hole — there was a presence there. Certainly, I had a lot to learn and experience to get, but that was a nice moment.”

Unlike academics, however, his acting career didn’t come without its struggles. “The work that I had done up until that point in my life, I didn’t have any credit in the acting world for it. No one gives a fuck, ultimately, that you went to Princeton and Yale.”

Without having built up much of an acting résumé yet, Duchovny was struggling to land the TV guest star roles he was primarily sent to audition for, leaving him to squeak by on his earnings from commercials. “I got tons of rejection. They’d reject me by saying, ‘He’s not a TV star. He’s a movie star,’” he says, before wryly noting the irony. “I didn’t have any money, so this ‘movie star’ couldn’t pay the rent.”

But sometimes the rejection wasn’t as flattering. Duchovny was frequently told he was low energy and that his acting was flat. “I still get that, and it still hurts my feelings. Whatever. They’re just feelings,” he adds self-consciously. “But it doesn’t feel flat on the inside. I feel full of life. I can’t help the way it’s coming out, that I’m not bouncing off the wall and trying to sell you something.”

Still, somehow, Duchovny knew acting would pan out. “I don’t know why,” he says. “I had no right to feel that way at all. I would think, ‘They’ll get it.’ I wasn’t just memorizing lines. I was going through processes and feeling things. I wasn’t super expressive about it, but I knew that somebody, sometime, was going to see it.”

Sure enough, his instincts were spot-on, with Duchovny soon deftly balancing roles in television shows (transgender DEA agent Denise Bryson in Twin Peaks, host and narrator Jake Winter of Red Shoe Diaries) and films (Kalifornia, Beethoven and Chaplin).

But playing Fox Mulder on The X-Files gave Duchovny his big break. And among the show’s legions of viewers was his former acting instructor.

“I think the role suited him really well,” Haufrecht says. “The character, except when it came to his science, was reticent and not revealing. You felt something was going on all the time, but he wasn’t open to showing the specifics.”

The sci-fi hit also attracted rock star enthusiasts, some of whom dropped by the set, including Barenaked Ladies (who famously name-checked The X-Files in “One Week”), which led to Duchovny joining them on stage later that week for their The Tonight Show with Jay Leno performance. He played the egg shaker and sang backup “woo hoo hoo”s.

The Smashing Pumpkins’ visit, however, landed Duchovny in hot water. “I got in trouble because I was sitting with Billy Corgan and he said, ‘I like Mulder’s watch.’ So I said, ‘You take Mulder’s watch.’ I thought it was just a cheap prop watch because that’s usually how it is. It just has to look good. It doesn’t even have to tell time. But then I found out later that I’d given him an expensive watch.”

The fervor surrounding the show extended to Duchovny, who became a ‘90s pop culture phenom. He hosted Saturday Night Live twice, had a cameo as Mulder on The Simpsons and graced a variety of magazine covers, including Esquire (where he was also one of 1997’s “Men of the Year”), Rolling Stone and GQ.

In 1999, Bree Sharp’s song “David Duchovny” not only secured her record deal — but it spawned a comedic music video filled with celebrity cameos, including X-Files co-star Gillian Anderson and Brad Pitt. There was also an ardent online fan community called the “David Duchovny Estrogen Brigade.” A red Speedo Duchovny wore in The X-Files’ second season ended up in the Smithsonian Institution. “I couldn’t be prouder,” he says in jest.

Duchovny also received a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame in 2016. “It’s cheesy and surreal,” he says, expressing ambivalence. “I’m proud of it. But it’s also meaningless in some way.”

He hung the plaque above his toilet. “Every time I pee I look at it,” he notes. “I think that’s the right frame of mind to have.”

Not particularly keen to discuss accolades or fame, Duchovny says he understands others’ fascination with the latter, but he doesn’t find fame to be particularly interesting. Except for iconic athletes Mickey Mantle and Muhammad Ali, not only did he not idolize anyone growing up, but Hollywood and stardom were so foreign to his existence that they were incomprehensible.

When tabloids first put Duchovny on their covers, he asked his mother how she felt about it. “She said, ‘I don’t know. You’re just my David. It doesn’t make sense to me.’ I guess that’s the way I feel too.”

In fact, as his celebrity soared, Duchovny grew increasingly ill at ease in public, frequently isolating when he wasn’t working. “It’s hard to be an artist because what an artist wants to do is observe, and when you’re famous you’re being observed,” he says. “Fame is bad psychologically. It makes you self-conscious. You’re not being normal. You can become used to the attention and feel good or bad about it, but you react to it and become reactive to situations.”

Illustrating his struggle to bridge the gap between fame and regular life — what Duchovny calls “the make-believe and the not” — he says Duran Duran’s “Ordinary World” periodically resonates.

But I won’t cry for yesterday

There’s an ordinary world

Somehow I have to find

And as I try to make my way

To the ordinary world

I will learn to survive

“From time to time, it’s been in serious rotation in my head,” he notes. “I would make it mean how hard it was to live a regular, beautiful life — walking from set to home, from fame to home, shuttling back and forth, getting whiplash between the two … How do you do it? ‘There’s an ordinary world…’”

Authenticity is crucial to Duchovny, who loathes pretension and disingenuousness (“I hate both those things. I have a very childish reaction to them. It’s very Holden Caulfield of me — very ‘Phony! Phony!’ It gets me pissed off.”), and whose understated acting technique hinges on conveying the raw truth of his characters in the least conspicuous manner.

“What do I really feel on a gut or soul level that I can bring to this that’s going to make it deeply authentic and not be bullshit? What can I do that is so fundamental and so subtle,” he says, elucidating his process. “If I can find that, then I feel like I can do it in a way that is particular to me and not just paint by numbers — and then I can apparently do so little [Laughs] — and yet I’m not scared, because I’ve plugged in on an existential level and I know I’m coming from a place that’s real.”

Whether it was honing in on Fox Mulder’s irreverence, Hank Moody’s candor or the anachronism of LAPD detective Sam Hodiak on the short-lived TV series Aquarius, Duchovny has cultivated a personal and idiosyncratic acting style, while moving fluidly between comedic and dramatic television and film roles. His diverse and noteworthy performances also include an alternate version of himself who has a crush on Garry Shandling’s talk show host character on The Larry Sanders Show, the romantic lead in Return to Me (opposite co-star Minnie Driver), a biology professor in sci-fi comedy Evolution and a hand model in Zoolander.

What’s more, Duchovny is just as versatile off camera. He wrote and directed episodes of The X-Files and directed episodes of Californication, Aquarius and Bones.

There have, however, been disappointments along the way. There were parts he wanted but didn’t land in The Doors (he auditioned for both Jim Morrison and Ray Manzarek); Sex, Lies and Videotape; White Men Can’t Jump and Flatliners.

Then there was the critically panned 1997 film Playing God, in which Duchovny plays a drug-addicted surgeon who loses his medical license and goes to work for the mob. It marked his first headlining movie role, appearing alongside Angelina Jolie and Timothy Hutton.

“That was really tough. It was sad when it wasn’t received well, and I was disappointed,” he says. “But I thought the movie was bad, so I didn’t disagree. I thought the script wasn’t there but that we’d play around and make it work, and that’s where I got into trouble. If I had been a different person, I’d have said, ‘No, this script isn’t ready. It doesn’t work. Let’s just not do it.’ But also, timing-wise, I had to get it done over a certain period. I didn’t have time to get the script to work because I had to go back to shooting The X-Files.”

Still, legendary film critic Roger Ebert attributed the film’s credibility to Duchovny’s performance, which he lauded: “He has the psychic weight to be a leading man and an action hero.”

It was more difficult for Duchovny to endure the negative reaction to 2004’s House of D, which took a brutal hit from critics and fared poorly at the box office. Duchovny wrote, directed and starred in the bittersweet and tender coming-of-age film alongside his then wife Téa Leoni, Anton Yelchin, Robin Williams and Erykah Badu.

“I haven’t seen it in a long time,” he says. “I don’t know what I’d think of it now. I’m sure I made first-time director mistakes and compromises I shouldn’t have, but there’s some sweetness to that movie that’s real. I think the sincerity of it was seen as strategic when it wasn’t.”

Beyond professional disappointments, Duchovny navigated weighty personal challenges at midlife. In 2014, When Californication wrapped after seven seasons, he found himself back in New York, alone and struggling as he went through a high-profile divorce after 14 years of marriage to Leoni with whom he has two children, West, 22, and Kyd, 19. He coped by channeling his emotions into writing novels and music.

His first book, 2015’s Holy Cow, was a New York Times bestseller. He’s since written three more. The Washington Post called his most recent book, 2021’s Truly Like Lightning, “provocative” and “entertaining,” “the best of the batch, and makes a solid case for him as a real-deal novelist.” Duchovny’s currently adapting it into a TV series. Earlier this year, he released The Reservoir, an Audible original that will be published as a novella next year.

Duchovny’s books, including several rooted in the surreal and fantastical, are populated by compelling and distinctive characters. He skillfully blends pathos, humor, sharp psychological insight and astute sociopolitical commentary while examining the nature of life’s myriad relationships.

In his songwriting, however, Duchovny solemnly and melancholically lays himself bare. “I’m an older gentleman, and I’m going to write songs about the state I am in,” he says. “I’m not going to write about necking in a car. I missed that time. I’m going to try to write about what I’m dealing with or what I’m feeling. I don’t write, ‘Don’t Worry, Be Happy.’ That’s not where I lean.

“Sometimes I feel like it’s too dark, but that’s what comes out when I sit down to make music,” he adds. “Not all of them are desperately bleak, but they are certainly experienced.”

Although Duchovny draws upon his life for artistic inspiration, he’s not seeking personal catharsis through songwriting. “The way I write, I try to make it as general as possible — what’s human, not what’s you or what’s me,” he says. “I am not interested in confessional songs. I don’t think confession is art. I think that’s just spewing. How do you transform that into something that’s healing, beautiful or art? The art part is making it universal.”

Indeed, it’s Gestureland’s sweeping humanity, as Duchovny ponders the past, love and heartbreak, that makes for a cathartic and commiserative journey for the brokenhearted and the ruminant, while also appealing to romantics and dreamers alike.

“I’m kind of obsessed with time as a concept and memory and love. They all kind of come together,” he says. “That’s the juice of poetry and songs. Regret and love and being in love and losing love. It’s not that I’m obsessing about these things, but if I’m going to sit down to write a song, I find myself going there.”

The opening track, the catchy, ‘90s-infused rocker “Nights Are Harder These Days,” finds Duchovny tapping into late-night anguish evoked by a reproachful lover from his past haunting his dreams and insomnia brought on by the guilt of not having detected a trouble friend’s warning signs before he died.

Duchovny sings, “I lay awake and count the ways that the nights are harder / Watching the numbers change / The minutes fading away…Yeah, the nights are harder these days”

As the song swells ferociously to its climax, McCusker’s frenzied, wailing guitar and Rowan’s pounding drums and crashing cymbals emulate a racing mind before tapering down to a final moment of calm, ending on a single, lingering guitar note.

On the mournful ballad, “Chapter and Verse,” Maria Kowalski’s heart-stirring violin underscores Duchovny’s grief as he ruminates on a past relationship. Vividly reliving every painful detail in his unrelenting mind, there is an especially poignant moment when Duchovny, sounding resigned, switches to spoken word: “Well, I guess this is the end”

The song’s chorus (“Got no plans but time on my hands / You on my mind and nothing but time / Got no plans and nothing to hide / Time on my hands and you on my mind”) came to Duchovny when he shot the most recent X-Files film several years ago. “I woke up in Vancouver and sang that chorus into my phone. It came to me like nothing else has ever come to me,“ he says. “I had it forever, and I didn’t have a song around it, so I sent it to the band and said, ‘Let’s try to write some verses around the chorus.’”

Beyond the perils of romance, Gestureland traverses politics on the lyrically pointed “Layin’ on the Tracks,” parental love on the affecting “Call Me When You Land” and the juxtaposition between the dark underbelly of Hollywood and cruising along the sunny coast on the breezy “Pacific Coast Highway.” Then, it all winds down with “Sea of Tranquility” (co-written with Simons), the plaintive closing track which finds Duchovny longing for connection and wholeness.

“Like a dying planet, something’s missing from my side,” sings Duchovny. “Like a moon, like a friend, like something from inside / I just keep on wandering deeper in the night”

Still, the chorus of the song remains optimistic: “Oh but one day you’ll find me swimming in the sea of tranquility / Yes and one day you’ll find me as high as I can be, as high as a man can be / Yes and one day you’ll look up and I’ll be free, oh free / Yes and one day you’ll find me swimming in the sea”

But “Sea of Tranquility,” named after the crater in which the Apollo 11 astronauts landed on the moon in 1969, isn’t the end of Gestureland overall. Duchovny is readying a deluxe package with bonus material, including unreleased tracks, for the winter holidays.

In the meantime, acting has also been keeping him busy. Recently, Duchovny received widespread acclaim for his self-satirizing cameo in TV series The Chair, and he voiced “Ice Cream Man” in the animated TV show Ten Year Old Tom. He’s also wrapped several upcoming films, including Judd Apatow’s The Bubble, M. Sayibu’s Adam the First and Lindsey Beer’s Pet Sematary sequel. Currently, he’s filming the untitled Kenya Barris/Jonah Hill Netflix comedy.

Owing to his prolificity, the media routinely calls Duchovny a “Renaissance Man,” which he addresses with his characteristic self-deprecation and droll sense of humor. “I’ve been called worse,” he says. “I like the Renaissance as much as anybody else.”

![Atari CEO and “Beat Legend: Avicii” Developer Discuss New Rhythm Game, Share Unearthed Photos of EDM Legend [EXCLUSIVE]](https://www.wazupnaija.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/atari-ceo-and-beat-legend-avicii-developer-discuss-new-rhythm-game-share-unearthed-photos-of-edm-legend-exclusive-327x219.jpg)