As part of a push to get our logistics unstuck, the president is prodding the Port of Los Angeles, one of the most important in the country, to operate on a 24/7 basis. This is welcome news, although it might cause most people to stop and think, “Wait a minute — our ports don’t already operate 24 hours a day?”

No, which speaks to the thick layer of irrationality that encrusts our supply chain. It’s beyond the power of any one person to change this anytime soon, but trying to scrape off as many of these encumbrances as possible should be a national priority.

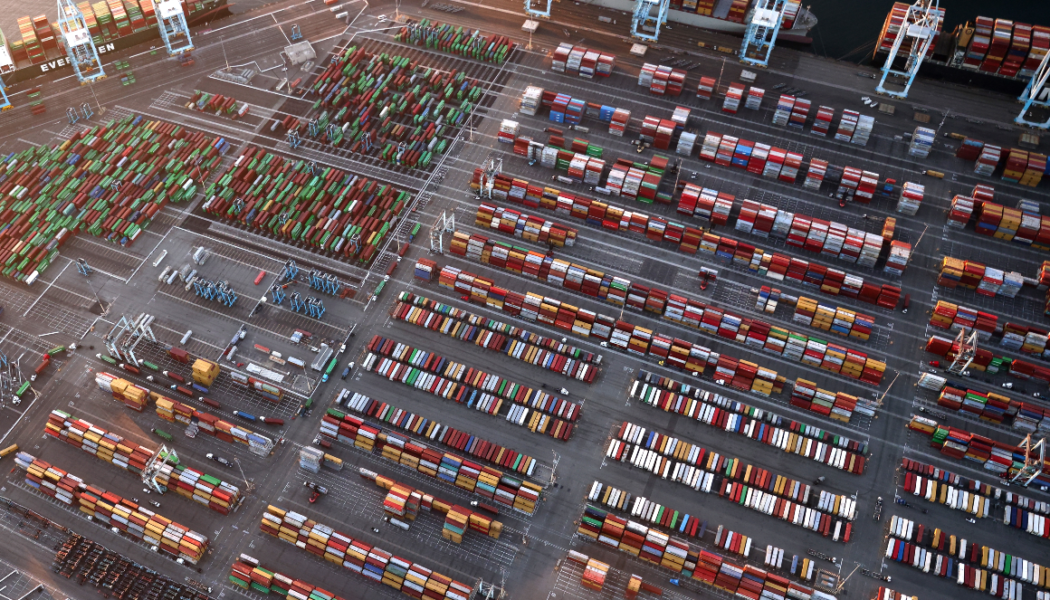

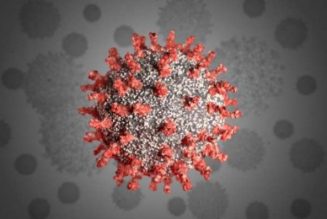

We are experiencing the worst disruption of the supply chain since the advent of the shipping-container era in the late 1950s, driven, at bottom, by the pandemic. A surge in e-commerce, coupled with a labor shortage, helped to create the conditions for a spiraling series of bottlenecks.

Ships are idling waiting to unload their cargo at ports, while containers are waiting at the ports to be shipped further inland, while cargo is waiting outside full warehouses on chassis that aren’t available to use to pick up other containers, and so on. In theory, there are plenty of ships, trucks and other capacity to handle the volume, but not if so much of that capacity is tied up and frozen in place.

So, there’s no underestimating the challenge here. Everyone along every part of the U.S. logistics chain is pointing fingers at each other, and everyone deserves some blame, whether it’s the ports, the truckers, the warehouses, the railroads or other players.

Yet the situation also highlights how, as Scott Lincicome of the Cato Institute persuasively argues, our logistics system is beset by idiotic policies and practices that make it hugely inefficient. There is a tendency in the political debate over infrastructure to assume that more — and more spending, in particular — is better, but it matters how you are making use of what you already have.

Consider our ports. U.S. facilities are nowhere near the top-performing facilities around the world. They are generally less automated and less efficient than those in other advanced economies. It takes, for instance, twice as long on average to move a container from a large ship at the Port of Los Angeles than it does at top ports in China. Ports in Asia operate 24 hours a day, matching the 24-hour-a-day pace of factories, whereas, until now, the Ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach were operating only 16 hours a day.

The White House made a pointed, if understated, reference to this in its recent fact sheet on its new logistics push, “Unlike leading ports around the world, U.S. ports have failed to realize the full possibility offered by operation on nights and weekends.”

Uh, yeah.

The main culprit for this massive inefficiency is the incredibly powerful International Longshore and Warehouse Union, which has a lock on the ports up and down the West Coast. It hates automation, and has won extraordinary pay for its workers (dockworkers make an average of $171,000 per year, with foremen making nearly $300,000) and strict work rules. When it negotiates contract renewals, the union can effortlessly snarl freight everywhere in the West — work slowdowns are its specialty.

As Peter Tirschwell writes in the Journal of Commerce, “Huge cost increases, limited ability to automate terminals, chronic avoidable disruption during contract negotiations, and far lower productivity and working hours compared with ports in Asia and elsewhere around the world are at the core of the issue.”

Notably, the highly automated Port of Virginia has been weathering the current crisis better than its counterparts.

Nothing comes easy in our current regime. The truckers have complained that various restrictions have made it difficult for them to make use of the additional nighttime hours that have already been available at the Ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach. In its fact sheet, the White House said 3,500 more containers will be moving at night, an incremental change in the right direction, but a drop in the bucket in the scheme of things. Tirschwell points out that’s about 3 percent of what goes through U.S. ports weekly.

Long-haul truckers around the country need about 20,000 more drivers, and have also been hit by a shortage of chassis. In the midst of a major logistical nightmare, the U.S. International Trade Commission imposed roughly 200 percent duties (on top of Trump-era duties of 25 percent) on the world’s biggest manufacturers of chassis, China Intermodal Marine Containers. The company does indeed benefit from unfair subsidies, but the timing of the trade commission’s action was hardly propitious. The head of the Harbor Trucking Association, representing port truckers on the West Coast, complained, “Now we’ve created scarcity and increased the cost.”

U.S. trade policy shouldn’t proceed heedless of the real-world consequences to the U.S. economy.

Then, as Lincicome points out, there are longstanding rules like the Jones Act, which makes it much more expensive to ships goods from port to port within the U.S., putting a premium on the over-taxed ground systems.

Eventually, U.S. logistics will get out of the current fix and reach a new equilibrium. Still, this crisis should prompt a rethinking of the needless inefficiencies we foist on ourselves. It will be too late to hold this coming Christmas harmless, but will serve us well going forward, whatever the season.