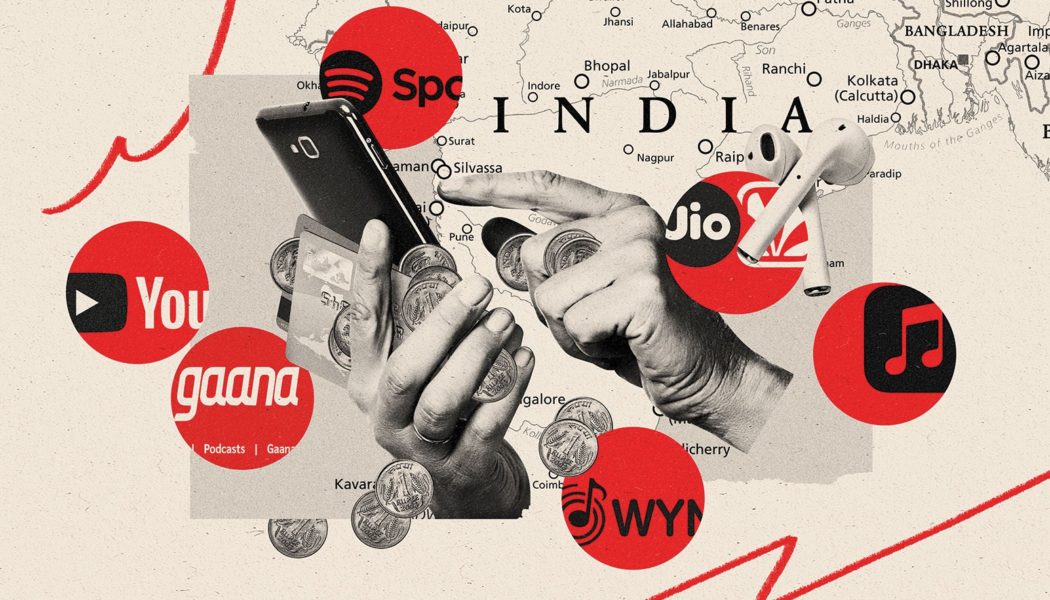

Only two countries — China (45% ad-supported), the seventh-biggest market, and Venezuela (58%), IFPI’s lowest-ranked sector — rely more on ad-supported audio streams than India (38%). And China, for the first time, generated more revenue last year from subscription-supported streams than ad-supported streams, IFPI figures show.

Lodha, who previously was an executive at hospitality chain OYO Rooms, says it’s time to change India’s revenue paradigm. To help Gaana regain its edge in India’s crowded streaming market against its well-financed competitors, he’s focusing on boosting subscription income, which he says is more important than hitting Gaana’s target of 500 million MAUs — a figure at which he says the streaming platform would finally turn profitable. Subscription income fell from 33% to 23% of Gaana’s revenue in the fiscal year ending March 2020, and 68% came from advertising, according to documents filed with India’s Ministry of Corporate Affairs.

It’s a shift India’s music industry will welcome — especially if Gaana’s rivals follow suit. Labels have long griped that the country’s streaming platforms are more focused on acquiring customers to help raise their valuations than on boosting revenue. India’s recorded revenue per capita was just 13 cents in 2020 — only Vietnam (10 cents) and the Middle East and Africa (12 cents) generated less, IFPI figures show. (The Indian Music Industry, which represents over 200 labels, estimates India’s overall streaming market exceeds 300 million MAUs.)

Indian consumers have proved stubbornly resistant to paying anything at all. While India has removed most of the barriers to a “healthy digital economy” — such as the availability of cheap data, affordable smartphones, convenient payment mechanisms and a range of well-marketed subscription options — what’s missing is a “good enough value proposition for premium music,” says Ed Peto, the founder and managing director of music industry services company Outdustry, which has offices in China and India.

In 2019, a month after Spotify’s arrival, Gaana and Indian rival JioSaavn slashed the prices of its annual subscription packages by over 60% to 399 rupees ($5.40), leading Apple to reduce its monthly fee from 120 rupees ($1.60) to 99 rupees ($1.30). The discounting did little to affect the level of paying subscribers for the Indian streaming platforms, which has remained around 3% to 4%, says the founder of an Indian digital music distribution service. Gaana won’t be reducing its prices any further, says Lodha. “If anything,” he says, “prices will go up.”

JioSaavn, for its part, is still trying to lure more paying users by offering lower prices. The platform plans to introduce, likely early next year, a “more affordable” package to “lift up our ‘freemium’ users to the subscription model,” says Keshav Bhola, JioSaavn’s vp content partnerships.

At Gaana, Lodha and his team have their work cut out for them. For the year ending March 2021, Gaana’s operating revenue grew 2.6% to 1.23 billion rupees ($17 million), while losses fell 7% to 3.27 billion rupees ($44 million). That followed a year in which revenue rose 53% to 1.2 billion rupees ($16 million) but losses ballooned 82% to 3.52 billion rupees ($48 million). These financial results have contrasted with Gaana’s claims of rapid user growth. The platform reported that its MAUs more than tripled from 60 million in February 2018 to 185 million in August 2020. (A year later, that sum has remained unchanged. Gaana has set a target of 250 million MAUs for 2021.)

Complicating matters, the platform’s parent company, Times Internet, doesn’t have the deep, in-house cash reserves of the profitable telecoms that own JioSaavn and Wynk Music, another popular streaming service. Lodha says he is nonetheless confident of reaching the half-billion MAUs goal in two to three years, by making “the product the best in class, from the search engine to the recommendation engine, playlists, look and feel,” and the volume and range of content. (Currently, in terms of content and features, there’s little to distinguish Gaana from its competition.)

The new CEO attributes Gaana’s flat growth last year to the pandemic, which reduced travel and, in turn, hurt music streams.

Raising prices in a country still recovering from a second pandemic wave would be a risky move, and Gaana is likely to seek another round of funding next year to help see its plan through, says Lodha. One likely source: Chinese tech giant Tencent Holdings, which already owns a 34% stake in Gaana, 60% of which is now controlled by Times Internet.

In June, the platform raised $40 million in convertible debt from Tencent Cloud Europe, a deal that values Gaana at around $570 million. (Potentially complicating matters, in China Tencent has been on the receiving end of an ongoing crackdown by anti-trust regulators, which has contributed to a falling share price.)

Gaana could also seek an initial public offering — but likely not just yet. “First, we have to become profitable,” says Lodha. “Once that happens, all avenues [available to] a successful startup open up.”

Additional reporting by Alexei Barrionuevo