Clive Sinclair, who invented the Sinclair ZX Spectrum, an early personal computer, died of cancer Thursday at age 81, his family confirmed. Sinclair was an inventor with an impressive list of electronic products to his name, some, like his pocket calculator, were quite successful, while others, like his Sinclair C5 “electric trike” vehicle, were decidedly not.

Born in England in 1940, Sinclair had a knack for creating gadgets. The Sinclair Executive “slimline” pocket calculator, released in 1972, sold well (likely in large part due to its low price ), and at one point was displayed at the Museum of Modern Art.

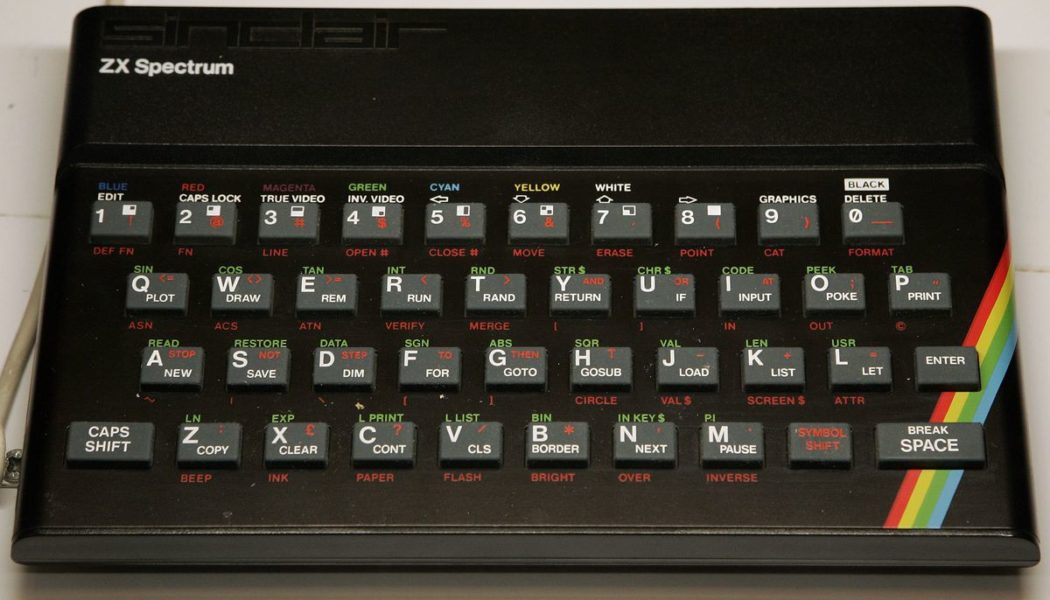

Sinclair’s ZX personal computers were priced lower than the then-popular Commodore 64, and well-liked by consumers in the UK. The ZX Spectrum (nicknamed “Speccy”) had a rubber keyboard and a color display, and eventually a library of thousands of games. The first model had 16KB of RAM and sold for £125 (roughly $170). The ZX Spectrum sold some 5 million units worldwide, before it was discontinued in 1992.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22860075/72224879.jpg)

But even many of Sinclair’s less successful inventions were later validated; Sinclair’s Black Watch, which used “integrated circuit technology” according to a 1970s print ad, didn’t really catch on, but looks it could have inspired some of the fitness trackers everyone wears on their wrists now. Sinclair’s TV80 pocket television wasn’t popular back in the day, but now we all carry little screens around with us wherever we go. And Elon Musk tweeted his condolences on Thursday, saying he “loved” the ZX Spectrum.

The Sinclair C5 electric vehicle, which launched in 1985 with a starting price of around £399 (roughly $550) wasn’t a hit with consumers either; you had to pedal it when the battery died, and when seated the operator was below the line of sight of most cars on the road. Oh, and there was no passenger seat: the C5 was a one-person vehicle. It’s probably a stretch to call it a precursor to the Tesla, but Sinclair was on to something, perhaps just a few decades ahead of the general public.

[embedded content]

“It was the ideas, the challenge, that he found exciting,” Sinclair’s daughter Belinda said in an interview with The Guardian. “He’d come up with an idea and say, ‘There’s no point in asking if someone wants it, because they can’t imagine it.’” And doesn’t that last bit sound a lot like a sentiment often attributed to the late Steve Jobs, about why he didn’t rely on market research for product development: “People don’t know what they want until you show it to them.”

Despite receiving a knighthood in 1983 for his contributions to the UK’s computer industry, and being a pioneer in the field of consumer electronics, Sinclair preferred his slide rule to a calculator. He said he found the internet and email “annoying,” and didn’t use them.

In addition to Belinda, Sinclair is survived by sons Crispin and Bartholomew, five grandchildren and two great grandchildren.