This article originally appeared in the February 1997 issue of SPIN. In honor of No Code turning 25, we’re republishing this article here.

Here is a joke Eddie Vedder told me. It wasn’t the only joke he told, but it was probably the best, and it bears repeating.

“How many members of Pearl Jam does it take to change a lightbulb?”

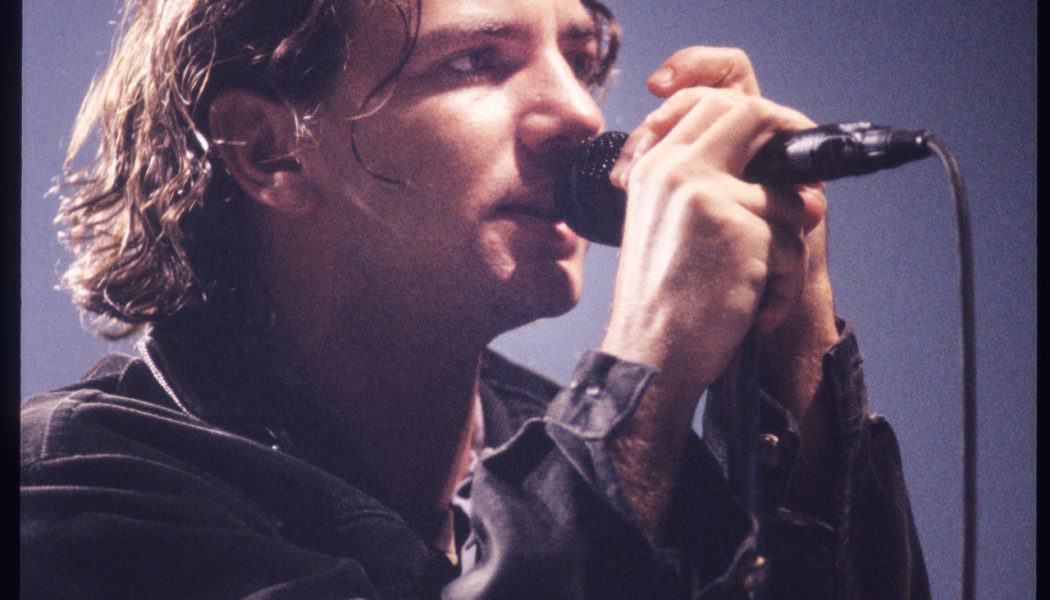

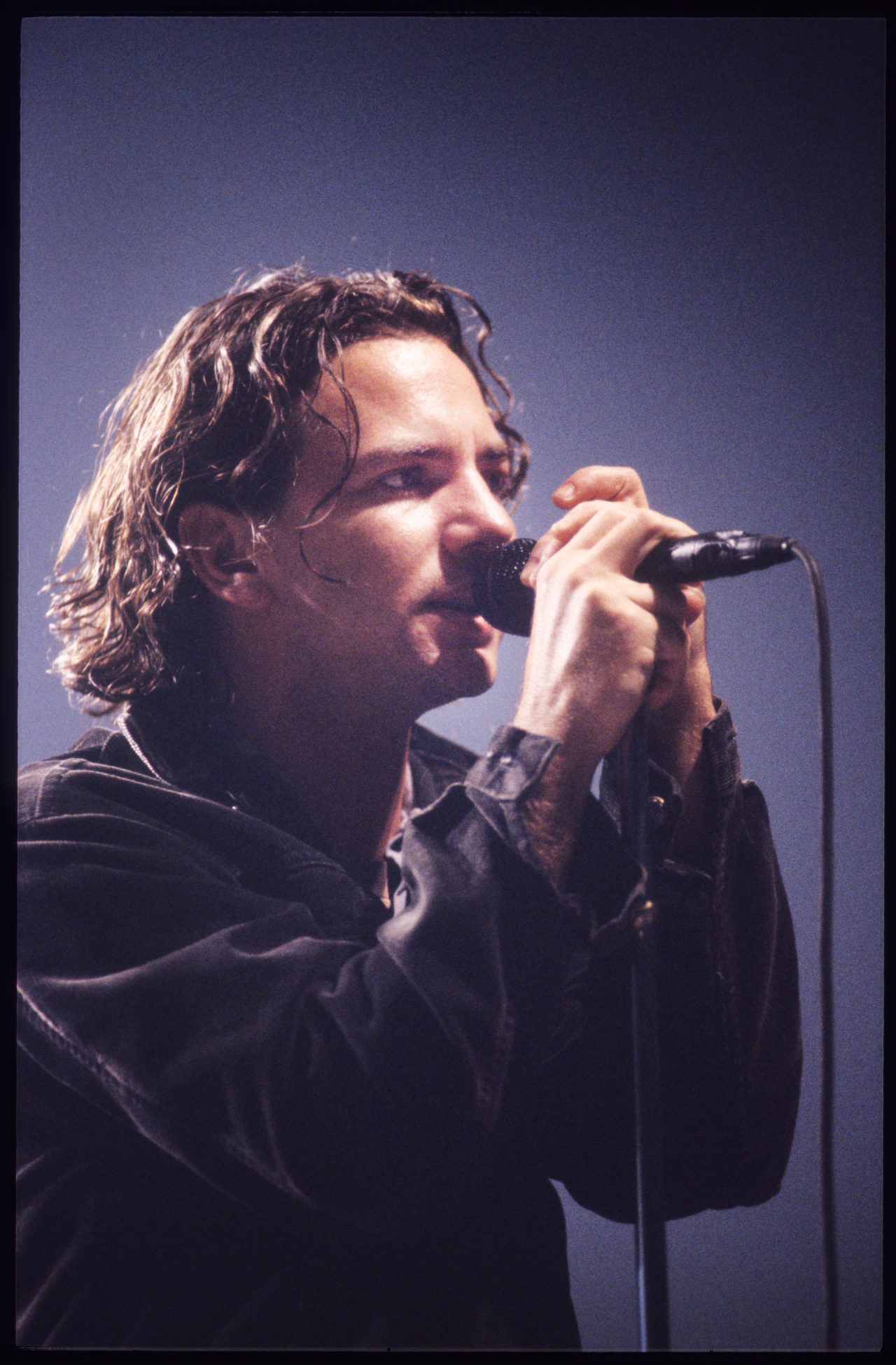

When Eddie Vedder asks a question of you, or you of him, or when he makes an important point, or when he shares something with you and wants a reaction, his eyebrows shoot up so they’re suddenly at right angles to each other. It brings to mind disbelieving girlfriends, mean teachers, and Satan. It’s an altogether unwelcoming look, and it’s immediately amplified by a steely glare and furrowed brow. For a moment—a long moment—you can’t help but believe those damning reports about Vedder’s dour disposition.

But then, just before you flinch, the tension is lanced by a grin. The grin is often set to his own words, and it’s a grin that’s less about self-satisfaction than about breaking the ice, than about inclusiveness. It’s a grin that says forget about what you’ve heard or read, I’m not that guarded, that somber, that paranoid, that humorless, that much of a pain-in-everyone’s-ass. It’s a warm, winning grin, and it works.

“I give up, Eddie. How many members of Pearl Jam does it take to change a lightbulb?”

Vedder stands up, screws his face into a mask of spokesman-for-a-generation pain, and yells: “Change?! Change? We’re not gonna change for anyone! Do you hear me? Not for anyone!“

For just over five years now, Pearl Jam—Vedder, guitarists Mike McCready and Stone Gossard, bassist Jeff Ament, and new drummer Jack Irons—have come to represent most everything that is right, or wrong, with rock’n’roll. They’ve been hailed as saviors, berated as frauds, lauded for their integrity, and ridiculed for their earnestness. They’ve been accused of flagrant careerism and of calculated anti-careerism. They’ve shown genuine empathy for their fans, yet they’ve made it exceedingly difficult for those fans to see them play. They’ve sold too many records, now they sell too few. A recent Rolling Stone cover story even went so far as to question the validity of Vedder’s expressions of anger and betrayal on the grounds that he was a gifted member of his high school drama club. Football team maybe, but drama club?

Pearl Jam have always presented an easy target for snipers. Gossard and Ament helped draw up the blueprints for grunge, first with the Stooges-like Green River, then with the more glam Mother Love Bone, but revisionists have dubbed them opportunists, not pioneers, overlooking the fact that the Seattle sound was always equal parts Black Flag and Bad Company. That Pearl Jam expressed more musical solidarity with the latter than the former outraged those who resented the connection. When Pearl Jam’s AOR-friendly grunge followed Nirvana’s purer version to the top of the charts, they were cast as villains by the indie-rock underground. When they outsold, outdrew, and then outlasted their contemporaries, the resentment grew further. And when they wondered aloud if being on top was so great after all, things got worse even still.

Such is the custom-made cross-to-bear that Pearl Jam carry on their backs. And it’s begun to exact a toll; the world’s most popular rock band is currently suffering through the first popular backlash of its career, and not just because they’ve recently discovered polyrhythms. They find themselves in the unfamiliar position of having a new record, No Code, praised by critics as a brave if not altogether successful departure but treated coldly by record-buyers, relative to the band’s three previous smash hits—Ten, Vs., and Vitalogy. (At press time, No Code has slid down to number 64 on the Billboard charts; according to SoundScan, it has sold 948,000 copies to date). This may bother me more than it does Vedder. “It’s great!” he says about the record’s sluggish sales. “We can be a little more normal now.”

It’s this quest for normalcy that has come to define Pearl Jam’s public identity and has begun to frustrate even their most devoted supporters. Perhaps the only sane way to deal with the crush of fame in the hyperaccelerated ’90s is to tease it, wink at it, blow it postmodern kisses, a la Bono and Michael Stipe. But Pearl Jam are fundamentally incapable of such irony or glibness. They’ve nixed making videos (their last clip was for 1992’s “Jeremy”), declined most every request for an interview, and battled a corporation, Ticketmaster, that no one much complained about to begin with, all of which has left fans feeling confused and resentful, unsure of why their favorite band won’t play ball like the rest of the alternative nation.

“There has to be a basic dialogue between your band and your public,” says Timothy White, editor-in-chief of Billboard magazine (and Spin contributing editor). “People want an ebb and flow of ideas, and they just don’t understand the degree of reticence that has crept up around the band.”

“We’re selfish,” shrugs Vedder. “We want it to be about the music. We don’t really care about any of this stuff,” referring specifically to interviews, but generally to anything that isn’t recording or playing. “We don’t feel we need to justify anything. We know where we’re coming from, and then it gets misconstrued, or people don’t understand certain things, like why you couldn’t play in San Francisco, or why you don’t participate with the music channel. You definitely feel like responding to a lot of this stuff, but then you realize that it just kind of goes away. As long as you focus on the music, all that stuff doesn’t matter.”

The funny thing is, Vedder and Pearl Jam seem to be able to handle “all that stuff.” Beyond Mike McCready’s bout with alcohol addiction (he’s been sober since 1994), they’ve avoided falling prey to the clichés that have become sadly synonymous with Seattle’s rock scene. Their lineup, with the one exception, has remained constant. So has Vedder’s 12-year relationship with his girlfriend-turned-wife, Beth Liebling, who fronts her own band, the space-jamming Hovercraft. Despite their private conflicts and public handwringing, Pearl Jam have emerged from a tumultuous half-decade of superstardom with their dignity, their integrity, and even their enthusiasm intact. Given modern rock’s current undignified state, and a music industry greedier than ever, that is no small feat.

Pearl Jam are both drawn to and embarrassed by their ethical and moral stands, not unlike the way heavy drinkers or sex addicts feel about their poisons the morning after. They build issues up, only to have to live them down. Sizable time must now be spent swearing on a stack of Sub Pop singles that they’re not frumpy killjoys. “We don’t bemoan,” Vedder laughs when I pose a question containing said verb. “I don’t want to be known as a bemoaner.”

So they’ve grown more and more comfortable with who they are, and who they are includes having escapist side projects (Ament’s alt-Eastern Three Fish, McCready’s brooding Mad Season, Gossard’s neo-funky Loosegroove label, Vedder’s meditative scattings with qawwali star Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan on the Dead Man Walking soundtrack, the group’s garage-band fantasies with Neil Young on Mirror Ball, cool hometown supporters (Mudhoney, the Fastbacks), and freaky celebrity friends (Dennis Rodman)). “We’re having a great time these days,” confirms Gossard.

Pressed, they’ll even admit that they enjoy being rock stars, so long as they can decide what that means. “We’re not going to look at the financial end and make decisions based on that,” says Vedder. “If it doesn’t feel right, we don’t want to do it.” Vedder looks at his bandmates and grins. “I’m kind of proud of that.”

It’s four o’clock on a bone-chilling Warsaw afternoon, and outside drab Torwar Arena, hundreds of bundled-up Polish kids are already milling about, their hands torn between the warmth of their coat pockets and the buzz of another cigarette. American rock’n’roll bands rarely include Poland on their European itinerary, and the November 1 Pearl Jam/Fastbacks concert has been sold out for weeks. “We’ll lose money playing here,” said Vedder later, “but I really thought we should do it.”

Inside, Pearl Jam have finished an ear-splitting soundcheck, withstood the trauma of a 15-minute photo shoot, and are now plopped down in their dressing room to sip some hot tea and discuss their new record. The mood is loose and amiable: “Keep it down, you freak!” yells Vedder through the wall to the Fastbacks’ Kim Warnick, who is loudly enthusing about something; “Fuck you, you fuck,” is her eloquent retort. Not exactly renowned for their sense of whimsy, Pearl Jam are visibly giddy when describing the word game they’ve been playing on the road. “You take a well-known person’s name and put it into a phrase,” explains Vedder. “Like, ‘I hope I die before I’m Bob Mould.’”

“Or, ‘SupermodelKimAlexisExpialadocious,’” beams Irons.

“LucIan MacKaye with Diamonds,” adds Vedder.

“Tie a yellow ribbon around Charles Oakley,” cracks McCready.

“This one’s a bit longer, but it’s good,” promises Vedder. “‘You may say I’m a dreamer / But I’m not the only one / I hope someday you’ll join us / Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan.’”

Such mirth is in marked contrast to my initial tug-of-war with the group two nights before. “So,” wondered Ament after 60 minutes of terse Q&A, “maybe you have some questions about the record, something more specific?” I wouldn’t go so far as to call them surly; Ament had been gregarious and kind, Gossard cooperative if guarded, Vedder likewise but more guarded still, McCready reserved, even shy. But the tempo, no pun intended, had been set by the recalcitrant Irons, Vedder’s longtime friend from his San Diego days, who shares the group’s disdain for all things media, and appears to have assumed the role of the band’s spiritual center. Irons, 34, who lives in Los Angeles with his wife and two kids, and who once committed himself to a psychiatric hospital after the fatal overdose of his then-Red Hot Chili Peppers bandmate Hillel Slovak, brings to Pearl Jam not just a supple presence behind the kit, but a Zenlike groundedness in the here-and-now that has helped the group navigate some stormy seas.

“Jack’s personality, maturity, and generosity have really helped us communicate with each other,” says Gossard. “It feels like this is how it was intended to be,” marvels Ament. “This should have been the band from the beginning,” states Vedder simply. Irons gently downplays his role as peacemaker. “It’s just a new relationship,” he demurs. “It’s just one of life’s adjustments.” He knows, though, how easy it is to get sidetracked by the extracurriculars. “The whole point is that we’re making music,” says Irons, echoing the now-familiar mantra. “We’re actually feeling something. And people can sense that.”

Irons is more than just a calming influence; his complicated beats set the rhythmic tone of No Code, from the moody drum circles of “In My Tree” to the Eastern swirl of “Who You Are.” “We realized that we had an opportunity to experiment,” says Vedder of recording with Irons. “For instance, everyone has written that ‘Who Are You’ was obviously inspired by my collaboration with Nusrat, but that’s not where it came from.”

“I’d been playing that [drum pattern] since I was eight,” says Irons. “It was inspired by a Max Roach drum solo I heard at a drum shop when I was a little kid.”

“When I first heard that song, I was totally blown away by it,” raves McCready. “I thought it was the best song we had ever done.”

But is it a single? “Who You Are” was the band’s hand-picked choice for the first radio track from No Code, an obviously difficult song that garnered little enthusiasm at radio and set the table for No Code’s subpar commercial performance. Vedder admits that the band’s selection of “Who You Are” was a “conscious decision” made partly to keep the size of their audience, and hence their lives, manageable, and that’s consistent with the album’s musical experiments. It’s not all odd meters and hushed ballads—”Hail, Hail” and “Smile” crunch nicely, while “Lukin,” “Habit,” and Stone Gossard’s kicky “Mankind” show real scrap and gusto—but No Code does challenge Pearl Jam fans to either accept the band as is, or else go listen to Seven Mary Three, Silverchair, or any other readily available source of vintage grunge. My own wish would be for them to reclaim the confident middle ground they occupied on Vitalogy; for all its good intentions, No Code is too insular, too stingy on pleasure. It’s easy to admire, but I wish I enjoyed it more.

“I guess we’re constantly trying to find a balance,” says Ament. “There are very obviously times with this band when everything’s been thrown out of whack, where things have felt crazy, where you’re just going with the clip and there’s no way you can go back and land. So consequently, there are times when we need to isolate, to figure out what we are doing with our lives.”

“Making No Code,” concludes Vedder, “was all about gaining perspective.”

Later that night, in front of 6,500 screaming Poles, Vedder’s words ring in my ears as I watch the band from the side of the stage. Contrary to published reports of Pearl Jam as cynical stars going through the motions, their two-plus-hour set is joyful and generous, studded with standards (“Even Flow,” “Alive,” “Jeremy”), obscurities (“State of Love and Trust” from 1992’s Singles soundtrack, Vs.‘s “Indifference”), and a rich sampling of material from No Code. And the No Code tracks do more than hold their own against the evening’s better-known songs; they overshadow them. Dirges on record, “Present Tense,” “In My Tree,” and “Sometimes” throb and twitch in concert like R&B slow jams; for the first time in their musical lives, Pearl Jam sound sexy. They’re playing not just to the cheap seats but to each other, with a tenderness and playfulness I would never have expected, and which the Torwar crowd connects with instantly. When Vedder introduces the next-to-last song of the night, No Code’s “Smile,” he makes no attempt to hide his emotions. “This is the happiest song we know,” he announces, “and this is for you.”

You haven’t really drunk deeply from the Big Gulp of democracy until you’ve seen a dance floor full of drunken Polish teenagers contorting their arms in unison to spell out the chorus to the Village People’s “Y.M.C.A.” It’s an otherworldly scene, made more so by the white face paint, witch hats, and mummy suits many of the patrons are sporting for this Halloween celebration. Then there’s the matter of my date for the evening, who, if I may speculate, doesn’t usually go in for this sort of entertainment.

“So,” Vedder turns and asks me, “uh, you want another beer?” It’s past midnight, and supposedly somewhere amidst the dry ice and pumping house music are Gossard and McCready. But an hour has passed since we were whisked into the club, and there’s no sign of Vedder’s mates. The closest we’ve come were a couple of female American exchange students who heard us speaking English and invited us to dance. Vedder, looking stricken, politely declined.

As the music heats up and the crowd thickens, Vedder and I duck into a booth and quickly order another round. The disco was Gossard’s idea—he’s a huge fan of hip-hop and R&B, though he draws the line at the more mechanical strains of house music—and Vedder’s clearly a fish out of water here. It’s not just the strobe lights and BPMs, either; Vedder, like so many celebrities these days, has spent the last two years defending himself, his wife, and his home against the maddening intrusions of a stalker, and he’s understandably gun-shy about chatting with strangers.

“What’s really sad about the whole thing is that Beth and I are the kind of people who’d love to ask some kid, some fan, into our house, you know, sit them down and play them records from our jukebox, that kind of thing.” Vedder finishes off his beer. “But we just can’t do that now.” Instead, he now passes the time at his Seattle home by tossing a ball around with the security guards that patrol his yard 24-7.

Little wonder, then, that Vedder feels so adamantly about keeping his mug out of the spotlight; he’s learned firsthand the dangers of overexposure. “Look at those,” he groans, pointing up to the American tequila posters and beer-bottle floats that hang from the club’s walls and ceiling. It’s as if he recognizes a former piece of himself in those advertisements, and he’s not going to allow his band to be turned into product again. Hence the boycott of “the music channel,” which has lately become anything but.

“The other night I was watching Alice in Chains on MTV Unplugged,” says Vedder. “I’ve known those guys for awhile, and toward the show’s end, I could tell that Layne [Staley] and Jerry [Cantrell] were sharing a real moment. It was pretty moving. And then one second later, some idiot’s screaming, ‘Take 50 guys, and 50 girls.’” He shakes his head in disgust.

“I’ve known Eddie before anyone even cared who he was,” says Soundgarden’s Chris Cornell, who first met Vedder in 1990 at a rehearsal for their side project Temple of the Dog, “and his attitude about things like that has been absolutely consistent. He’s never been interested in selling millions of records. That band has taken an amazing amount of risks throughout their career. New bands could learn a lot from them. I’ve learned a lot from them.”

If Eddie Vedder has a blind spot, it’s this: He believes in heroes. You’d think that the deception he suffered as a kid—he was led to believe by his mother that his stepfather, for whom he felt little, was his real dad—would have curtailed such leaps of faith, but mention any number of musicians to Vedder and you can plainly see that his emotional investment in them borders on the devotional. When he tells me that Bob Dylan recently sold the rights to “The Times They Are A-Changin’” to a financial company for use in a commercial, he looks as if he’s lost his best friend. “I can only hope that it’s some kind of ironic joke,” Vedder says with little conviction. Later, he takes extraordinary pleasure in recounting, song-by-song, moment-by-moment, the solo set he’d seen Pete Townshend perform a few weeks before, and I just don’t have the heart to challenge him on Townshend’s dubious past 20 years. Even when he’s garrulously sharing asides on his all-time favorite TV show, Batman, and talk turns to some of the more titillating revelations in Burt “Boy Wonder” Ward’s tell-all autobiography, Boy Wonder: My Life in Tights, Vedder can’t help but wear his Bat-heart on his sleeve. “I wish he hadn’t revealed so much,” he murmurs.

Vedder loves his boomers—Young, Dylan, Townshend—the ones who extended olive branches to an adolescent San Diego boy struggling to find an identity. He’s indebted to them, and he’s a man who repays his debts. A vital difference between Nirvana and Pearl Jam was that Nirvana, offspring of the Sex Pistols, never trusted a hippie. Pearl Jam, offspring of the Who, couldn’t wait to jam with them.

But Vedder doesn’t let just anyone into his hall of fame, and if you look closely a pattern emerges: Membership is limited to artists who have enjoyed unusually long runs, in part by making willfully difficult music that whittled down the size of their audience. None of the above-mentioned icons sell many records anymore, and only Young continues to contribute to the language of rock, but all three can still pack concert halls, and with varying degrees can still summon the spirit of their greatness. They’ve remained faithful iconoclasts—the same can be also be said for more contemporary inductees such as ex-Minutemen bassist Mike Watt and recent retiree Johnny Ramone—and when Vedder looks in the mirror, it’s their reflections he hopes to glimpse. At 31, he may not be ready to cut the cord quite yet, to write a big fuck-you like Trans or Slow Train Coming. But he’s plainly willing to sacrifice some record sales, even some audience goodwill, in order to maintain control over his art and his life.

“Hopefully, people will continue to extend me the benefit of the doubt,” says Vedder. “If not…” His voice trails off for a moment, but comes back strong. “Well, I’ve gotten a lot, and I appreciate it all. But I could also see myself trading it all in.”

Which is precisely what Vedder did on June 24, 1995, at San Francisco’s Golden Gate Park. “It was amazing to me how unsympathetic some people were to the situation,” recalls Ament. “Neil [Young] happened to be there; we were making a record together so we knew a bunch of songs. He dragged us back out there. We had our heads down, we were like, ‘Oh my God, this is the worst fucking day.’”

Ament, of course, is referring to the nadir of their ill-fated 1995 tour, when, due to a mix of food poisoning and general exhaustion, Vedder walked offstage after only seven songs, leaving Neil Young and the four remaining members of Pearl Jam to finish off the set. Two days later, physically and emotionally drained, they canceled the remainder of the tour. “I think we all agreed that it had gotten insane, that it was no longer about the music,” says Vedder.

What had supplanted the music was a furious battle with the nation’s dominant ticketing agency, Ticketmaster, and the band’s subsequent attempt to tour the U.S. without playing Ticketmaster-controlled venues. A 1994 squabble over service charges snowballed into an obsession that nearly tore the band apart.

“We were trying to keep our ticket prices low,” recalls Kelly Curtis, Pearl Jam’s manager since their inception, “and we were finding that in a lot of cases, the service charge was changing randomly. Sometimes it would be five bucks, sometimes it would be eight, and we didn’t understand why. And the response was a very cocky Fred Rosen [president of Ticketmaster] saying, ‘If you guys are stupid enough not to make what you’re worth, then I’m going to make what you’re worth.’ They wouldn’t even print their service charge on the tickets. It looked like we were charging, say, 26 bucks for a ticket when we were really only charging 18. My brother, who’s a lawyer, turned me on to another lawyer, and he thought it was all very interesting, and the next thing I know the Justice Department is calling…”

In May 1994, Pearl Jam officially asked the United States Department of Justice to investigate Ticketmaster on antitrust charges, alleging that the company’s 1991 buyout of Ticketron resulted in a Ticketmaster monopoly over ticket distribution in the country’s arenas and stadiums. When Pearl Jam tried to mount a summer 1994 tour using non-Ticketmaster facilities, they claimed that Ticketmaster had used its influence to successfully pressure promoters to boycott the low-cost tour. Instead of appearing before thousands of moshing fans, Ament and Gossard found themselves appearing before the far more sedate House subcommittee on Information, Justice, Transportation, and Agriculture, testifying that they “should have the freedom to go elsewhere if Ticketmaster is not prepared to negotiate terms that are acceptable to both of us.” (In July 1995, the Justice Department dropped its investigation; analysts believe that because venue owners and promoters willingly entered into the exclusive contracts, the Justice Department had no choice but to clear Ticketmaster.)

Unwilling to back down from their now very-public stand and still hoping to tour the U.S. on some scale, Pearl Jam began employing upstart ticketing agency ETM Entertainment Network on their summer 1995 tour, impressed by the company’s system, which included tickets printed with the purchaser’s name and an individual bar-code to prevent scalping, 8,000 phone lines to ensure responsive service, and a service fee of only two dollars. “Their service is so much better [than Ticketmaster’s],” attests Curtis. “You don’t have to have a credit card to order by phone. You don’t have to have advertising on the ticket. It wasn’t the ticketing that fucked that tour up.”

The real problems were the still-scarce number of feasible alternate venues and the intense scrutiny the band was now under. The tour’s opening show in Boise, Idaho, had to be relocated to Casper, Wyoming, after a ticketing dispute with Boise State University. On June 5, less than two weeks before the tour’s kickoff, the San Diego Sheriff’s Department demanded that the band move two shows scheduled for the Del Mar Fairgrounds to the Ticketmaster-controlled San Diego Sports Arena, citing fears of insufficient security. On June 17, yet another show was canceled, this time due to torrential rain and hail. By the time Pearl Jam reached San Francisco on June 24, they had just four completed concerts to show for their considerable efforts. A rancid room-service tuna-fish sandwich was the last straw.

“I needed a sick day,” says Vedder, “and you can’t necessarily do that in this job. There are 50,000 people, and they’ve all come to this place, and—oh, it was just brutal.” The band had had enough windmill-tilting, and they called an end to the tour.

But less than 48 hours later, having cast off the pressure of having to play, Pearl Jam realized that they still wanted to play. “Two days later we were calling each other on the phone,” says Vedder. “There were songs that I was really excited about playing, that everyone was excited about playing.”

“We needed to regroup,” adds McCready. “We sat and talked for a good four hours about all kinds of things.”

“Within a week,” finishes Vedder, “we had rescheduled every one of those shows.” And it was after the band’s July 11 makeup gig in Chicago that they quietly booked time in a local studio and began laying down tracks for what would become No Code. Why begin making a new record so soon after flirting with disaster? “The theory is that rather than meet up after you’ve been away for two months and don’t recognize each other, you go in while everyone’s fingers are flexible and our voices are warm,” says Vedder.

But how did the emotional baggage from the tour play itself out on No Code? The answer can be found in the humble, almost New Age meditations of tracks such as “Sometimes” (“Seek my part / Devote myself / My small self / Like a book amongst the many on a shelf”) and “In My Tree” (“Up here in my tree / I’m trading stories with the leaves… / Wave to all my friends / They don’t seem to notice me”). With nowhere else to turn, Pearl Jam turned within.

“I learned to, what’s that martial arts phrase, Jeet Kune Do,” says Vedder. “You know, where someone comes at you with a whole bunch of energy and you just use that energy to let that thing knock itself down. Don’t get in there and try to wrestle those things that are so much bigger than you; just divert that whole energy and let that thing trip over itself.”

Did recording with such renowned Zen masters as Ali Khan and Young provide any shelter from the storm?

“Singing with Nusrat was pretty heavy,” says Vedder. “There was definitely a spiritual element. I saw him warm up once, and I walked out of the room and just broke down. I mean, God, what amazing power and energy.”

“And we learned so much from Neil,” says McCready.

“Yeah, he’s got a really quiet wisdom,” says Ament. “He’s not beating you over the head with his, um, big book of wisdom.”

“I’d never felt, for lack of a better word, as high as when I’d look over and see Neil playing lead on ‘Down by the River,’” says McCready.

“We get along like old neighbors when we’re in the studio,” says Vedder. “It’s as comfortable as can be. But when you’re on stage playing with Neil, well—it’s one thing to be at the zoo and watch an animal pace around its cage. It’s another to be in the cage with him.”

So, I ask Vedder, seeing that you’re hobnobbing with rock stars, not to mention basketball divas, are we really supposed to buy that bit about you being “a book amongst the many on a shelf?”

“You know, you people have given me so much shit for that line. Like, ‘yeah, fucking right, you’re that guy.’ But you know what?” Vedder looks me straight in the eye. “I am that guy.” Then he motions around the room. “We are that guy.”

On the night before the Torwar show, Vedder wanders into the hotel bar at about 6 P.M., notebook in hand, eager to share with me a song he had just written. His face is flush with pride, his eyes beaming. I rub my hands in anticipation, hoping for a scene like the one in Don’t Look Back where Bob Dylan unveils “It’s All Over Now, Baby Blue” to a stunned and select few.

“This is called ‘Room Service Tray,’” Vedder announces, his eyes buried deep in his own handwriting. “And it’s from the point of view of one of those room-service trays, and the tray, it always feels left out because people eat off it and then just cruelly leave it outside for the maid to pick up, wash off, and send to yet another room.” Vedder glances up and tosses me a wide, knowing smile. “I think that this proves that I can find the pain in anything.”