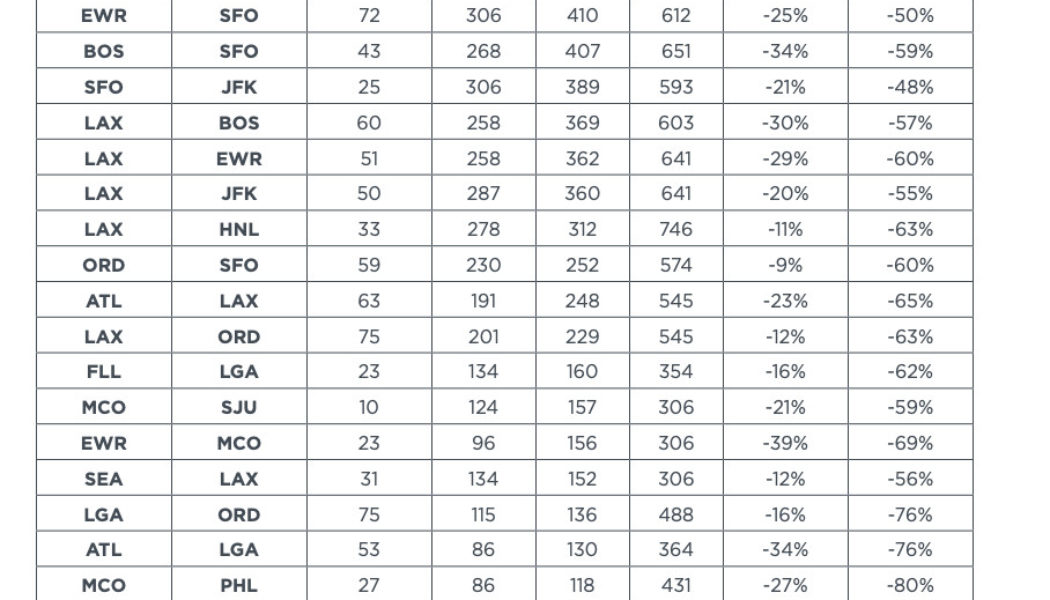

One way jet-setters can cut down on climate pollution from aviation is to choose more fuel-efficient itineraries — if they can figure out which flights pollute least. A passenger on a more fuel-efficient itinerary might generate 63 percent less carbon dioxide pollution on average than a passenger traveling to and from the same locations on a less efficient itinerary, a new report found.

There’s even more good news for consumers concerned about climate change: cheaper flights tend to be more fuel-efficient and thus less polluting. Itineraries among the cheapest 25 percentile of plane fares actually cut passengers’ emissions by about 55 percent compared to the most polluting itineraries, the report found. It’s possible airlines are passing on savings from the fuel efficiency of newer or more densely packed planes to their customers, the report posits. Its findings are based on an analysis of estimated emissions from 20 popular domestic routes in the US in 2019.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22732755/image001__3_.png)

But for passengers to make informed decisions, airlines will need to divulge how much pollution each of their flights creates, and that information isn’t widely available yet. There’s a push from advocates to mandate that disclosure — kind of like policies in some places that require restaurants to tell customers how many calories are in each of their dishes. The researchers estimated emissions based on how much fuel was likely burned for each itinerary. The Verge spoke with Xinyi Sola Zheng, one of the authors of the new report by the nonprofit International Council on Clean Transportation. Zheng shared some tips for finding the most efficient flight paths and other strategies for cleaning up skies.

This interview has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

More people are starting to fly again as pandemic restrictions loosen. What can they learn from your study about the emissions from their flights?

If you are to look for lower-emitting flights without knowing the exact emissions, which is what this study is ultimately advocating for, you can follow some more general rules like flying direct and flying on a newer aircraft. Usually, when you have a layover, your routing is less efficient. You’re going on a slight detour or a big detour depending on where this layover is.

You can usually see the type of aircraft that a specific flight uses when you book a flight nowadays. The newest would be like an A320neo and Boeing’s 787. That newest generation aircraft are, in most cases, more efficient and lower-emitting than other alternatives.

But as we discuss in the paper, that’s not always the case. So ideally, we still want the actual emissions data. Before that happens, consumers can try to rely on more generalized rules. And if they’re more flexible with their destination or if they’re going to somewhere that’s not too far, then maybe consider a trip using rail or car.

Paying to offset emissions from flights seems to be popular with consumers and airlines now. How does choosing a more efficient flight compare to buying offsets?

There are almost no aviation sector offsets available. So whenever you’re paying for offsets for flights, you are paying for the emissions reductions happening in other sectors. Yes, they help reduce emissions in the grand scheme of things, but it’s not asking the aviation industry to claim its own pollution. They’re just ultimately outsourcing their problems to other industries if everyone just continues to fly and fly often.

The quality of offsets and then the price of offsets all vary. Currently, the offset prices don’t really represent the actual social cost of carbon emissions. Some of the projects, they might not actually reduce emissions. It’s widely known in the environmental community that offsets are pretty concerning in terms of their quality. For consumers, it is important to think about, like, if you’re already trying to reduce your carbon footprint — try to do it right. We should try to push for decarbonization within aviation.

Trying to choose a lower-emitting itinerary, even if it costs a little bit more, I think that’s a little more real and more tangible choice to make if you’re trying to make an impact. And as the study already shows, normally, you can find a lower-emitting option without paying more or without paying a whole lot more.

There’s been a lot of focus on “flight shame,” holding individuals responsible for greenhouse gas emissions from their flights. But what about the airlines themselves? What responsibility do they have when it comes to their emissions?

So I do think we’re seeing airlines and aircraft manufacturers increasingly recognizing the pressure from the public. That’s why we’re seeing a lot of announcements for net-zero greenhouse gas emissions targets and for investments in alternative fuels. Those are trends, but what I think is more important is the actual action that they take under these commitments. It is important for them to invest in technologies that are still in their early stages.

But at the same time, there is a lot of potential around fuel efficiency. Ideally, airlines should all think about their fleet renewal plans and try to retire older planes a little bit earlier and purchase some of the newer aircraft to refresh their fleet. As the aircraft grows older, its fuel efficiency also deteriorates. During COVID, especially last year because of the traffic downturn, a lot of airlines already saw an opportunity to restructure their fleets. They retired a lot of aircraft earlier because of reduced demand. That’s a good thing from the environmental perspective.

And if airlines begin disclosing the emissions for their flights, what impact could that have?

We hope people will be more aware of their carbon emissions associated with flying. Ultimately, we’re hoping that the consumers are voting for lower-emitting flights and technologies with their dollars. One person’s choice is not going to affect the entire operation, but a lot of people’s choices will be a very big incentive to airlines. It comes down to consumer preferences as an incentive or an influencing force to the market so that there is a signal to airlines that there is demand for lower-emitting options.

I think the airlines have more or less heard of the idea of emissions disclosure. Everyone’s sort of waiting to see if this is going to become a regulation or if at some point everyone is going to do it. This study is sort of a primer for showing what kind of information consumers would be getting if emissions disclosure becomes a real thing.