Trial lawyers say whoever tells the best story wins. And love her or hate her, in her memoir Rememberings, Sinéad O’Connor tells a case-winning story of her life. Of the Americans under 30 who even know her name, most probably have it archived with #pretty, #skinhead #onehitwonder, #SNL and #meltdown. Three of these hashtags derive from the event that shit-canned her career: when the global pop star closed out a gig on Saturday Night Live by displaying a photo of the Holy Father of the Roman Catholic Church, declaring “Fight the real enemy!” then tearing the photo — and her life — in two.

This is lost in translation to YouTube, but in 1992, that Pope-icide really wasn’t a crowd-pleaser. “Total stunned silence in the audience,” she writes, going on to report not seeing a single person backstage as she made her way to the dressing room, then exit, then outside to get egged on the sidewalk. By Monday, major media were calling O’Connor a blasphemous twit, shrill loudmouth, spoiled brat, and other synonyms for bitch; two weeks later she was booed off the Madison Square Garden stage in a Bob Dylan tribute concert. And she remained essentially banned for life from the media’s main stage.

Even if subsequent headlines didn’t vindicate her views, the events in her book leading up to SNL all tumble with a domino-chain inevitability. Growing up in Ireland, a small country run by the Catholic church, where abortion and divorce are both illegal, Sinéad is regularly tied up and beaten by a mentally ill mom who keeps a photo of John Paul II on her bedroom wall. At 12, she watches Bob Geldof celebrate the Boomtown Rats’ single having bumped “Summer Lovin’” from its week-long reign at number one by showing up on “Top of the Pops” to rip up a photo of Olivia Newton-John and John Travolta. At 21, she’s a major-label recording star, at 24 a global icon, and at 25 so un-stoked by all of this that she retreats into a New York City rasta community whose spiritual elder tells her “The Pope is the devil and the devil is the real enemy.” The week of SNL, she sees an Irish newpaper’s exposé of abuse and predation within the Catholic Church, an article whose main surprise is making it into print. She takes a cab to 30 Rock carrying the photo of John Paul II that she took from her mom’s wall after she died.

From this account, the only weird thing about any of this is that she kept getting asked about that night many years after the fact: Did Sinead O’Connor know what she was doing? Does she regret being self-righteous? At least that’s what I asked her, for this publication back in 1998, and ever since, as I followed her career and life — through media scandals that include posting details of her sexual practices, tweeting that all non-Muslims are “disgusting,” declaring “I’m a dyke” then retracting it, and appearing on Oprah, on Dr. Phil, and in various world religions — I’ve been stuck in a chicken-or-the-egg quandary about Sinéad O’Connor: Was she more traumatized by life events that compel her to speak out or by the vilification she got for doing it?

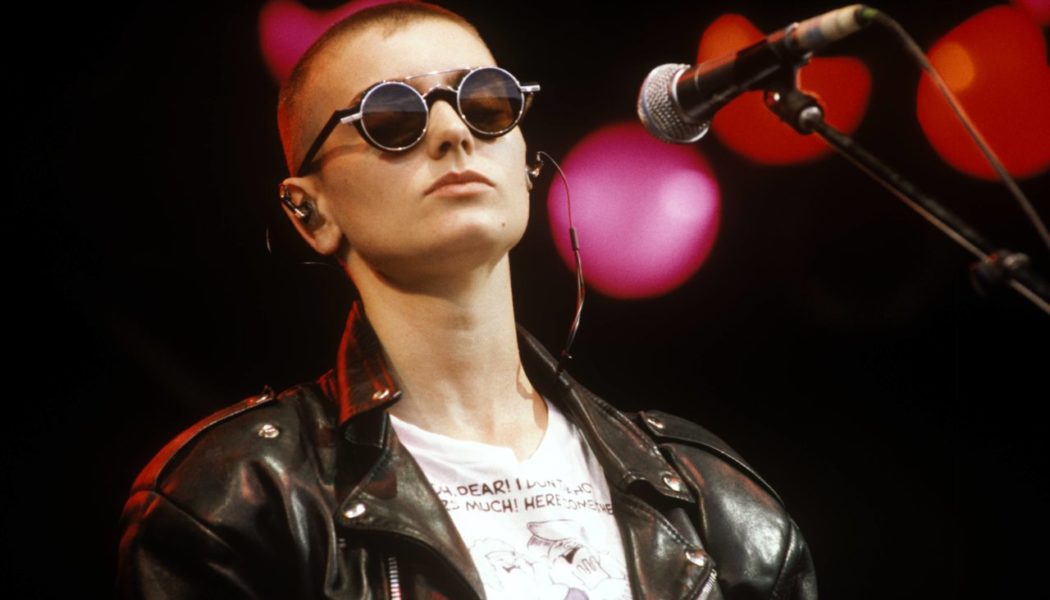

As you can see from some of the newly-published photos in her memoir Rememberings, Sinéad O’Connor was, and likely is, disruptively magnetic. After chatting with her for only about two hours, I was so comfortable with the smart, funny, petite, soft-spoken, (and to be frank, more than slightly attractive) single mom that I put a question to her as I would to a buddy: Ever wanna tell your younger self “Oh c’mon, shut up”? She rolled with this in our talk — “Yeah, but I’m not gonna say, ‘You all were right. I’m a complete wanker’” — but later on, she faxed me (this was 1998) several pages of earnest, respectful, handwritten self-advocacy that was so touching and so revealing most of it wound up in the piece. By today’s light, it was also indisputably right. “I am a good and loving person and I deserve to be treated with love and respect” she faxed. This, in a period, her book reveals, she was seeing a shrink six times a week. But back then, outside her safe space, that stark assertion was only unnerving.

At 25, Sinéad O’Connor got a horse-killing dose of what it actually means to be “cancelled” — without a string of sex-assault charges or, say, blowing up a daycare center. She got it years before the Dixie Chicks were vilified for opposing the war in Iraq, or Taylor Swift was sued by a DJ for saying that he’d groped her, before #MeToo and a host of victims’ groups, and before everyone figured out that calling an outspoken woman “crazy” is usually a pathetic attempt to change the subject.

But now, after social media set the fame bar low enough to include thought leaders in personal grooming, it’s hard for many people to believe that someone might actually try to lose a million followers. Many still believe that celebrity makes you bulletproof, and that vindication protects you. None of this is the case with O’Connor, whose bolder statements often weren’t about any discernible cause.

Back in 1998, her former publicist told me: “Here was this incredibly talented woman who was inevitably going to ruin her career and there was nothing I could do to stop it.” Which certainly jibes with O’Connor’s claim in her book: “I feel that having a number-one record derailed my career.” she writes. “And my tearing the photo put me back on the right track.” Maybe that track would never have been straight or easy.

A little less than a decade ago, O’Connor began writing this memoir, getting as far as the SNL affair before an emergency hysterectomy prompted a series of nervous breakdowns that wiped her memory clean. She resumed the book about two years ago, in what she says is a different voice although it’s quite recognizably her. She picks up after her international shaming, when she returns to Dublin to study the intensely personal form of classical singing called bel canto. This has her begin singing in her natural accent, embracing the unfettered soul singing of Irish sean-nós that had already been in her vocal signature.

She begins writing frank, personal songs about family members past and present, making a turn into therapeutic chamber-folk that’s as much a middle finger to rock expectations as her Grammy-snubbing, Pope-shredding was to stardom. She appears as the Virgin Mary in Neil Jordan’s killer film, The Butcher Boy. She has flings with Peter Gabriel, dubmaster Robbie Shakespeare, along with the four fathers of her four children, plus the three other men she married, and an impressive roster of supporting characters. She attempts suicide on her 33rd birthday.

That’s the maddening thing about Rememberings: how strong, resourceful, and fuck-what-you-think its author’s actions often seem, yet how fragile she sounds relating them, how deeply the wounds cut. This is a memoir by someone who says she’s lost her memory. Its main consistency may be in its depth of feeling, which often feels transliterated from music itself. Yes, she writes, she really is crying in her arresting video for “Nothing Compares 2 You.” But she often cries while singing, whether it’s a folk ballad or showtune. “Some songs, you just even think about them, you cry,” she writes. “Like ‘America the Beautiful.’” She gives an absolutely convincing account of a visitation she had at five, cozying up to her grandma’s piano and whispering, “Why do you sound sad?” and hearing “Because I’m haunted.”

It’s clear we miss half the story if we’ve never heard the 54-year-old sing. Her front-page dedication includes “Qui cantat, bis orat”: “Who sings well prays twice.” That almost genetic musical spirituality runs throughout, aligning superficial incongruities like her rejection of Roman Catholicism’s patriarchy and devotion to Jesus Christ, the Holy Spirit, and the dozen-odd priests and nuns who’ve helped her out. But even those who haven’t heard her will find a uniquely sharp, insightful, and funny book in Rememberings, which is clearly written in her hand, and gives a wealth of the specific insane experiences no author can ever invent. An epic failed attempt by a grade-school nun to give O’Connor’s class a chalkboard-illustrated sex-ed class; a post-scandal Chelsea Hotel hideout where she drops acid with a late-stage Dee Dee Ramone; getting force-fed soup by Prince in a private audience/kidnapping that ends with her escaping by foot to hitchhike back to Los Feliz. And you’ll find no other book with a sentence like this: “After I actually leave Jon Bon Jovi, I go up the road to see Dónal Lunny and we end up making love, and I conceive my third child.”

Without trying, Rememberings forces you past contradictions like “tough yet tender,” “strong yet fragile,” and other mental clichés that male journalists, or maybe males, often fall into with powerful female artists.

It’s good to read, a few months ago in The New York Times, that O’Connor had settled into a remote Irish cottage and had a tight crew of single ladies from the hood. “We bury bodies for each other,” she said of her friends. But I’m sure her piano is still haunted and won’t let her be silent long. That’s the strongest pull of this exceptional memoir, its sense of a powerful, everyday truth about creative humans, a truth only found in the accumulated details of one human’s unreproducible life.