Upon its premiere on Netflix in 2019, Tuca & Bertie was the animated talking bird sitcom we didn’t know we needed. Created by Lisa Hanawalt, an award-winning graphic novelist and illustrator who served as production designer and producer for the beloved Netflix animated series BoJack Horseman, the series was met with rave reviews, and immediately earned a dedicated fanbase of cosplayers.

If you have no idea who we are talking about, Tuca & Bertie chronicles the delightful friendship between Tuca (voiced by Tiffany Haddish), an impulsive toucan that balances a series of gig economy jobs while trying to maintain her sobriety, and Bertie (voiced by Ali Wong), an anxious song thrush that balances a boring desk job with dreams of becoming a baker.

With its blend of character-based comedy, bizarre jokes, stacked vocal cast (Steven Yeun voices Speckle, Bertie’s insanely sweet boyfriend; and Reggie Watts brings a foppish air to Pastry Pete, Bertie’s baking mentor) and incisive social commentary (Bertie eventually has to call out Pastry Pete for being a creep) Tuca & Bertie seemed destined to fill two voids: the “strangely human show about weird animals” void created by the impending end of Hanawalt’s old show (BoJack creator Raphael Bob-Waksberg serves as an executive producer of Tuca & Bertie) as well as the “wacky feminist show about mismatched female friendships” void created by the end of Broad City.

Instead, Netflix — who created its reputation, in part, by saving prematurely canceled shows such as Arrested Development that had deep fanbases — canceled the show after only two months, declining to order a second season. Perhaps this is proof that the alpha streamer is losing its touch.

Fortunately, Walter Newman, the vice president of comedy development at Adult Swim, began pursuing the Tuca & Bertie team for a deal. After staying grounded for two years, the second season premiered in June on Adult Swim. (Episodes air Sundays at 11:30 p.m., right after Rick and Morty, and are also available on the Adult Swim app.) The series remains as whimsically weird and touching as possible, finding time for judgmental plant people, Tuca’s “sex bus” (don’t ask) and an honest look at how aggravatingly tough, but necessary, it can be to find a good therapist.

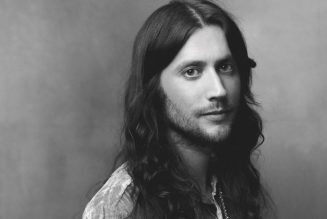

Hanawalt is hopeful that the second season of Tuca & Bertie is a new beginning, as she’s got a lot more bird stories to tell. A few days after the season two premiere, she spoke with SPIN about second chances and how to avoid easy buzzwords when crafting topical comedy.

SPIN: It’s well known that Netflix doesn’t share viewership information, which is very frustrating for creators. Were you surprised that Tuca & Bertie got canceled only two months after it premiered, or did you see it coming?

Lisa Hanawalt: No, I was surprised. They made that decision much quicker than after two months, right? We were only able to tell people then. I felt very confident that we delivered a really good show — based on the critical response and feedback from people who were watching the show. It really seemed like it was connecting with people. We were definitely blindsided.

It’s been pointed out that it was a bad look for Netflix to cancel a show with two women of color as the leads so quickly after it premiered.

I mean, I would like it to not be remarkable that the show features women or has a cast with people of color in it. That shouldn’t be the most important thing about the show. But that’s the landscape we’re in right now, that it still seems remarkable or rare for some reason, which is kind of a bummer. I would like more shows to have that demographic. I think more and more are coming out, but they don’t always get as big of a chance as those shows with more traditional white male creators.

For now the show will be released week to week, and there are a little more restrictions on Adult Swim than on Netflix. Has that changed the way you’ve approached making the show?

Not really, I’ve always liked the show to have an episodic feel in addition to having the larger story arcs go throughout the entire season. I want each episode to feel special so that you can drop in at any moment and understand the self-contained little story of the episode. So I just leaned into that a little harder, knowing that it would come out weekly.

Where did the idea for the show come from? Was it something you came up with as BoJack Horseman was winding down, or has it been percolating in your mind before that?

I had made this webcomic about Tuca for Hazlitt and Bertie kind of came out of this comic I did for Lucky Peach, where I made a comic about a bird couple getting a new house, so those characters turned into Bertie and Speckle. And just at some point while working on BoJack, Raphael started asking me if I had an idea for my own show, and I had been starting to think about it a little bit. So then we just talked about it for a few years and very slowly developed this idea.

So BoJack had anthropomorphic, talking animal creatures, but it did feel more or less based in our reality. But Tuca & Bertie has sassy talking plants and pedometers that smell farts, so it’s a lot more outlandish, in a way. Did you consciously want this show to have a very different feel from BoJack and not exist in the universe of that show?

BoJack is really Raphael’s show — he wrote it. I had input and I illustrated the backgrounds and characters and art directed it, but I really didn’t have much control over the scripts, which is fine.

I love BoJack, but when it came time to do my own show, we really went to my sketchbooks, my art, my writing and picked out what we liked and what seemed like a good show — it’s really my world. I would always joke when working on BoJack that I would put in a plant person and Raphael was like, “No, that’s against the rules!” But when it came time to do my own show, it was, “OK, now all this crazy stuff belongs.” I still think it’s very grounded in reality. It’s just like the surface of it is a little more cartoony and surreal and objects can come to life and talk if they need to.

You’ve been in the animation and illustration game for a while, but like you said, this is your first time running a show. What’s it been like to be the person in charge?

I’m really glad I had years of experience working on BoJack. I think if I’d gone directly from being an independent cartoonist to running my own show, that would have been a very difficult transition. I think I just learned to trust my team. It can feel strange when you’re used to working alone to open it up to all these other people collaborating on it.

I don’t actually do much drawing on my own show. I make notes here and there, but I really kind of hand over the reins to Alison Dubois. She’s a friend of mine who is the art director and she does a better job than I ever could. She’s actually much better at drawing a lot of things than I am, and it makes the show better. I can hand the script over to our supervising director — this year was Aaron Long — and he can say, “I don’t understand the scene, and also this is the fifth montage you’ve had this season already.” So, “OK, throw it out, make it better. Let’s put in something different.”

So much of the show is about mental health, from Tuca maintaining her sobriety to Bertie dealing with childhood trauma. In this season, she’s trying to find a therapist. Often, these issues can sometimes feel like buzzwords that people just throw around. Are you using your show to interrogate how serious people are about mental health issues?

A lot of my stories come from what I’m interested in and what me and my friends are going through and I never want to do a really simplified take on it. I try not to do stuff that feels too trendy, but maybe it does just because it’s in the zeitgeist and because I am an elder millennial [Hanawalt is 38]. To some degree, I can’t avoid that. I mean, it’s nice that more and more people are destigmatizing and seeking help for mental health issues. I support that.

Our first episode is about Bertie seeking a therapist, but a lot of the therapists she meets are really bad. They suck. They’re not going to help her. It’s not that simple. It’s not going to fix all her problems. I hope to always do a slightly nuanced or twisted take on whatever I’m interested in.

There’s an episode where Pastry Pete is trying to make a comeback after getting called out for sexual harassment. There’s been a lot of talk about cancel culture, and I watched my screeners the day after Jeffrey Toobin got rehired at CNN, which made me wonder to what extent powerful men are facing the consequences for their actions. When you’re talking about topics that are so omnipresent, how much of a challenge is it to find your own take so you don’t say the same things everyone else is saying?

When I’m working on the script, I don’t want to feel like I’m just repeating something I’ve read online or that I’ve seen a take of on Twitter. It’s hard to avoid, but in episode three we dip into how people who should be, quote-unquote canceled are not. They come back, they don’t just go away and disappear. But I don’t think we even use the word canceled in that episode, because to me, these words are buzzwords or jargon. You hear them so much that your brain just starts to shut down when you hear them. So I want to avoid that shutdown.

It’s rough because sometimes those words are helpful. But I want to explore these ideas without hitting these easy markers that we’ve already decided how we feel about them. You say the word “cancel” and people are either yes or no. It’s a very black-and-white response. I want to get into that gray area as much as possible, which is hard to do within a 22-minute cartoon. I mean, it’s a very silly show. It’s not like it’s not going to be as serious as an hour-long drama. But we do our best.

How do you know when you have the right balance of silly jokes but also thoughtful commentary on important and often sensitive subject matter?

It’s how I feel when I’m watching it over and over again. I watch each episode 100 times, just watching the animatics and replaying every scene. It feels almost like we start with a serious issue or whatever I’m interested in for the episode. And then all the jokes are like a glaze on top that you can either add more of the glaze or take some away. It’s very easy to add or subtract jokes.

The underlying structure or meaning of the episode is the hardest part. How do you make an episode about gentrification without it seeming very, very pat or very easy? I don’t know. And I don’t know if I succeeded, but a lot of it is just “OK, here’s what I’m thinking of. What is a unique angle on this? Or how would our characters react in this environment? What is the problem with this relationship?” That’s always underlying in each episode.