This article originally appeared in the August 1996 edition of SPIN. With Biography: KISStory airing tonight, we’re republishing the story here.

Whoo-hoo, it’s a firehouse inside Gold’s Gym, a Hollywood sweatbox packed with waiters looking to be actors, actors looking to be bodybuilders, and bodybuilders looking at their reflection in the mirrored walls. In one corner, Paul Stanley, singer and rhythm guitarist in Kiss, and at 44 its youngest member, strains against the forces of nature as he hangs from the Gravitron. The man usually seen with a huge star across his face is, this Saturday afternoon, seeing stars. He may be masked for a living, but momentarily, dangling from the Gravitron, Stanley’s face contorts into a mask of pain.

“All right, let’s do it!” barks Anton, the official Kiss trainer. Stanley hunkers down in a device known as the Roman Chair and performs three good sets of lateral raises. As a reward, Anton hands him an amino-laced sports drink.

“The guy’s an animal,” says the drill sergeant in the Kiss Army. And the proof is in the pecs: Stanley is indeed a fine physical specimen, arriving here five days a week to sweat out the ’80s.

“It’s not my choice,” he says through clenched teeth. “Too many people are expecting too much this summer.”

Lock up your eight-tracks and dust off your daughters: Kiss are back. Jimmy Carter was president when drummer Peter Criss got the boot from Stanley, Gene Simmons, and Ace Frehley back in 1980. Two and a half years later, guitarist Frehley left to pursue a solo career. Something calling itself Kiss—Simmons, Stanley, and assorted ringers—has recorded and toured on ever since, though they took the makeup off the market in 1983. And somewhere right now, too, there’s a dinner-theater production of Man of La Mancha.

But something unexpected happened earlier this year, as the modern lineup—Stanley, Simmons, Bruce Kulick, and Eric Singer—prepared for “surprise” cameos from Frehley and Criss in an MTV Kiss Unplugged special. The lawyers talked, then the musicians talked, and they discovered that after all these years they liked talking to each other. They looked nervous, possibly uncomfortable together again, on Unplugged, but an irresistible force had been set into motion.

The original foursome—classic makeup, classic costumes—have reunited for a two-year-long world tour. They sold out Detroit’s—that is, Rock City’s—38,000-seat Tiger Stadium in 47 minutes, front-row tickets scalping for $7,000. A set of live tracks culled from the 1975 Kiss Alive! and 1977 Kiss Alive II era entitled You Wanted the Best, You Got the Best!! was released in June. The group that once clocked Doctor Doom are teaming up with the X-Men for a new Marvel comic. God knows there’ll be new Kiss merchandise, new Kiss action figures, perhaps even another Garth Brooks Kiss cover. Everything but new Kiss songs: The set list is pure 1978 and earlier. The golden years. Before they can even think about recording a new album, they have to see if they can get through the summer together without anyone spitting up real blood.

“Right now we have no plans to do anything other than to take this one step at a time,” says Stanley. “If we look too far in the future, we won’t be enjoying the moment.” Or as Van Halen once philosophized: “Only time will tell if we can stand the test of time.”

Kiss’s tour is the cowcatcher on the hard-rock railroad crossing the country this summer: Metallica headlining a Lollapalooza that also features Soundgarden; the Scorpions doubling up with Alice Cooper, Def Leppard recording again; and Iron Maiden, Deep Purple. Warrant, and Slaughter all on the road.

But if the summer of ’96 is a new iron age, it’s not a new age of irony; Kiss have been apart for so long that they can’t possibly occupy the same niche in the pop consciousness. What was once contemptible comes back collectible. The kind of people who’d call you a fag for liking Kiss in high school are going to be shouting it out the loudest for them this time around. Kiss split up as the biggest, richest joke band in the history of the universe, disparaged by hipsters and rock critics coast to coast as showbiz. But these days, everybody wants to be in showbiz: Darius Rucker and Trent Reznor sing Kiss’s praises; Pearl Jam’s Mike McCready toted a Kiss lunch box to school; Courtney Love was turned in by her mom for boosting a Kiss T-shirt when she was 12. Indie rock scenes from every industrialized nation on earth have issued Kiss tribute albums. They went out as cheese, and they come back as, well…fromage, anyway.

Kiss have the highest recognition factor of any brand name in America: for millions, thoughts of high school, of first sex or the first time you threw up in the backseat are trademarked Kiss, all rights reserved. Their stage-wide, megawatt-burning logos autographed your corneas; even when you shut your eyes, you saw their name in lights. Kiss brought salesmanship right out into the open of rock’n’roll. And that’s what fascinates today’s Kitsch Army. Kurt Cobain was a Kiss fan for all the right reasons—they rocked—and for the irresistible wrong ones—because they made it easy to pretend it’s all a con.

And now, by some strange pact signed in blood and comic-book ink, Kiss return as elder statesmen. They’ve become gods to a generation that was young enough to prefer Lancelot Link and the Evolution Revolution the first time around. J Mascis got into Kiss when he was a college student at the University of Massachusetts in the mid-’80s, learning guitar while listening to Ace Frehley’s solos. “But I can’t duplicate the master. He’s got this low vibrato that’s hard to imitate.” Should Kiss request him to open on the summer tour, Mascis is characteristically terse: “I’m ready,” he says.

They’ve inspired others to imagine the lowest common denominator, like the moon and the stars, as something worth shooting for. “The Troma team is clearly part of the Kiss Army, no question about it,” says Lloyd Kaufman, co-founder of Troma Pictures, the bottom-feeding studio that brought you such pop rocks as The Toxic Avenger and The Class of Nuke ‘Em High. The studio formed in 1974, the same year Kiss debuted; if you could bang your head to a movie, it would be one of Troma’s. Their latest, Sgt. Kabukiman N.Y.P.D., tells the tale of a Bronx cop who inexplicably morphs into a martial arts warrior, one who bears a hardly accidental resemblance to Kiss’s bassist. “We thought about calling the picture Sgt. Gene Simmons N.Y.P.D.,” claims Kaufman. “Sometimes we need superheroes to battle the forces of evil.”

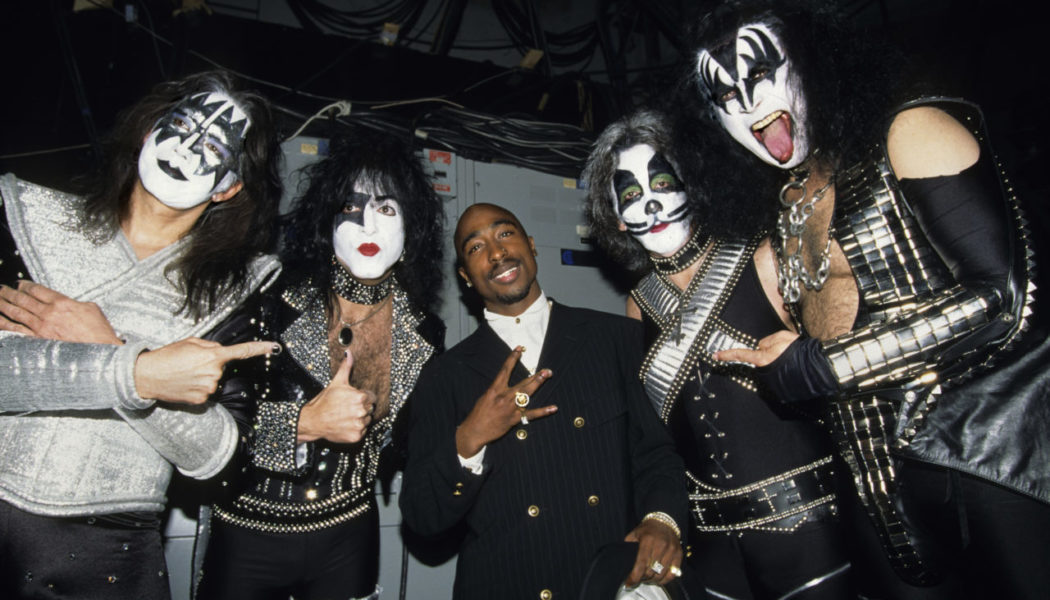

Kiss looked grand booking grunge ornaments Stone Temple Pilots as their opening act, like they were sharing their heaviness with icons of a generation too freaked to enjoy the glory. Then, when singer Scott Weiland’s addiction jeopardized everything, Kiss looked all the grander by comparison. Weiland can’t deal with success? Lemme tell you about success, kid. The band has sold over 75 million albums worldwide, and is four releases shy of eclipsing the Beatles’ record 29 gold albums. Kiss had an ice cream and a toothpaste named after them; love guns and wastebaskets molded in their image. Just a few months ago, they made an appearance at the Grammys with Tupac Shakur, and Mister Tough Guy looked humbled. Hey, when asked to loan some costumes for an exhibit, Kiss told the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame to take a walk (well, the actual words were more like, What do you mean it’s a charity?).

With so much expected of them, Kiss can’t just slip into costume and go through the motions. This time out they have to blow more shit up, be bigger, grander, louder, and stupider than ever. It will take some preparation. Months of a demanding physical and mental regimen are required.

“When we sat down together,” says Stanley, “I said to the guys, ‘We’re training to fight Tyson.’ ” He sounds like Kevin Costner narrating a Civil War documentary. “And if we can’t go in there and whip his ass we better stay home, because false bravado and any delusions we have about who we are will go right out the window the first time you step up there and meet the enemy.”

Is he worried? His huge jaw sticks out a little further, like he’s daring me to throw the first punch.

“I predict a first-round knockout.”

After his workout, Stanley heads across the street to the small rehearsal space where Kiss is putting its game face on. There are no costumes, no makeup; just musicians getting in sync after years of atrophy. They are scraping a decade and a half of muck off the songs, getting them into shape, too: metal squeezed into a pop jacket, Rolling Stones blues riffs, Zeppelin screaming, and Detroit-band feedback made gregarious, all individualistic excess driven out.

That’s the goal, but in the studio they can’t quite agree on how their monster hits went. The rehearsal should be posted on the Internet: That way every time Criss and Simmons disagree on a drum line, a nation of Kiss fans could e-mail the proper lick. The vibe is loose, friendly; is it boom-boom-boom-boom I wanna rock and roll all night, or….

But then a funny thing happens. They roar into “Deuce,” and as the band vamps the ending, Frehley, Stanley, and Simmons line up at the front of the “stage,” old movements and fragments of choreography coming back to them with no apparent consciousness. Stanley brandishes a wicked moue, and then the three whip their guitar necks in tandem, first toward heaven, then to hell. The endorphins have kicked in. There is nobody in the room but a crew member and a journalist, but suddenly we are all in Budokan. Gym rats do not lie: Muscle memory is a reality.

Like a hairdresser who becomes a Hollywood producer, or a porn star who resurfaces as a respectable disco diva, the Sunset Marquis Hotel has seen other days. As surely as vices can turn into habits, so in Hollywood, where history is measured in minutes, can habit turn into institutions. Gene Simmons, 46 years old, sits by the hotel pool, casting a steady gaze across the water. It’s a classy establishment these days, with white tablecloths on the tables and cellular phones on the tablecloths. But Simmons remembers staying here early on, when this celebrated hotel was, well, a dump. Rock bands holed up on the cheap, leaping off the second-story balcony into the swimming pool. For a moment, it’s almost as if he wishes things could be like that again.

“It’s time to change,” says Simmons. “It’s time for everybody to lighten up and enjoy life. There are no world wars. There is no Communist menace. There are still little evils around the world.

“There is still—” He looks vaguely distracted. “There are still very large breasts about to jump in the pool.” Water splashes the patio, and Simmons refocuses. “There is still man’s inhumanity to man and all that. But if you take a broader point of view about history, times are good. And even in the worst of times, I want Kiss to be able to go up there and lighten the load a little. For two, three hours, let Kiss take you away.”

Even if he’s not leaping off the balcony in six-inch-platform dragon’s-head boots, these are the best of times for Simmons. He’s putting aside the Hollywood turn his life took—managing Liza Minnelli, dating Cher and Diana Ross, starring in Runaway with Kirstie Alley. He plays them off as diversions now, junkets that distract you from your day job.

He’s a rich man—”Trinkets? You go buy a fucking car, I want land”—about to get richer. Kiss reportedly stand to make between $35 million and $50 million on the world tour, and they’ll owe a lot of it to reputedly the best businessman in the group. When Simmons was bargaining with agencies to promote the world tour, one report had him “accidentally” leaving his date book behind in an agency’s office, opened to pages itemizing (golly, could they possibly have been inflated?) bids from other agencies.

Gene is Kiss, says Peter Criss. He’s the prime conceptualist, the first face fans think of. If Kiss has inspired more rumors than any other band in history, more of them are about him. Was he replaced by a clone when his movie career began? (Actually, the clone wrote the songs to The Elder.) Is that really a cow’s tongue sewn on? (It’s all Simmons, and he does exercise this muscle.) Does he spit real goat’s blood? (The official story is it’s an evil mix of melted butter, food coloring, ketchup, eggs, and yogurt.) Did he and Ace really make out onstage? (This rumor probably started with one of Frehley’s tumbles off his platforms, perhaps into Simmons’ waiting arms.) And what’s the deal with that hair? (Indeed.) He enjoys it when people pay attention.

So as he sits in the courtyard at the Sunset Marquis, it’s with a certain expectation, shading into impatience. He wants to get things going, he says, and show other bands how it should be done. Gene’s world has little time for mopes.

“I spoke to Kurt before he died,” he says. “I was trying to get him to do a Kiss cover for the Kiss My Ass tribute record.” Simmons goes into an imitation of Cobain’s joyless voice: ” ‘Gene, it’s a real thrill to talk to you.’

“I was gonna go, uh, you don’t sound like it. You don’t sound like a man who’s white, and ergo has certain advantages that—let’s call it what it is. If you’re black or Hispanic or another minority you could complain, ‘I don’t get treated well….’

“But a blond white boy. The center. You are the popular culture. You’re in a famous rock’n’roll band, you have no right to be upset—about anything. You were molested as a child, you were raped by a bear, I don’t give a shit. You’re now the idol of millions. The American Dream really does exist, it really paid off: You can call Uncle Sam bullshit, call the President a moron, and they still give you money and women still want to have your babies.”

About this time the waitress arrives, having picked up a signal from Simmons.

Waitress: “Did you want something?”

Simmons: “I didn’t. You’re easy on the eye. You’re good to look at.”

She blushes and throws him a puzzling smile.

“Thank God I am in a band,” he continues. “Because I am the ugliest guy on the face of the planet, but my goodness, do I get a lot of puss.” He’s saying this after the waitress has left.

“There are some fringe benefits to being in a band. You get paid awfully well. Your ego gets satisfied all the time. You get good seats at restaurants. You can buy whatever you want.

“But mostly, the ugliest sons of bitches in the world, who happen to be in bands, get laid all the time. And you don’t have to be a hound.”

On cue, the waitress arrives again.

Simmons: “When does the floor show start?”

Waitress: “What?”

Simmons is richly self-possessed and extremely intelligent, throwing off informed asides on the Children’s Crusade or German silent-movie actors two at a time. He’ll eventually get back to answering my question of 20 minutes ago; right now he’s picking up on something he just said.

“I’ve never been high in my life, except in a dentist’s chair. Never been drunk. My room was a deal room in college! My roommate was a dealer, and I didn’t have a clue what was going on. I was too busy hunting puss. I get that.”

When called a confirmed bachelor, Simmons demurs. Try “free spirit”: he gets that. He lives with the woman he’s had two children with. He’s just not ready for marriage.

“I have two kids, they’re the most important thing to me. I really care about their mom, we’ll be together in some way for the rest of our lives. That’s a lifetime commitment. But I refuse to be a cartoon.”

You and Duckman, both. Still, one has to admire Simmons’s candor on most subjects. He truly does not care what anybody else thinks, so why not say what he’s really thinking?

Anybody who gets married without a prenuptial agreement, Simmons counsels, should have their head examined. “Marriage unfortunately starts with the romance and fantasy of ‘I love you, it’ll go on forever.’ If it falls apart, it becomes a business. I refuse to be in that business. I’m in the Kiss business.”

He may be the president of Kiss, Inc., but he’s also a member—Simmons has never stopped feeling like a kid in a scrappy rock’n’roll band pitting itself against the world. His secret weapon is that he has never fit in.

Maybe that’s why Kiss’s music sounds so rootless. Give Kiss credit for a heroic degree of A) concentration, or B) obliviousness. It was 1972 when Stanley’s and Simmons’s first band, Wicked Lester, fell apart, and the two rummaged around for a new direction.

Their new band rehearsed on 23rd Street in Manhattan. The Chelsea Hotel was practically next door; Max’s Kansas City, second home to Andy Warhol and his coterie, was within walking distance. The Mercer Arts Center scene—the New York Dolls, Suicide, etc.—was coming to life, a whole new language of sleaze and style. Kiss were casting for a sound but absolutely nothing that was going on around them penetrated the membrane.

While the Velvet Underground mocked the hippie’s no-cost utopianism, and the Dolls speared their high-mindedness with every frou-frou and garbage-can beat, Kiss never even noticed; they acted as if neither hipsters nor hippies even existed. Their music wasn’t a “reaction” to a counterculture that was coming to an end. It was an end unto itself. What do you think about the environment, an interviewer once asked Paul Stanley. “Fuck the environment, man. We are the environment” was the answer.

Besides, who needed Andy Warhol when you had Neil Bogart? Born a Brooklyn kid surnamed Bogatz, he was a Catskills singer, then a record promoter, then divine architect of bubblegum music, and ended up mapping out disco. He and Kiss had to find each other. It was Bogart who hired Amaze-O the magician to teach Simmons how to breathe fire, his idea to release four solo albums simultaneously in 1978. Bogart sponsored a Kissing contest early on, and when the band appeared at an Illinois shopping mall to award the winning couple, he threw dollars from above so that the crowd would form around the band. The winners appeared with Kiss on the daytime Mike Douglas Show. Sitting next to comic Totie Fields, Simmons went into his I-am-devil-spawn shtick. Finally, Fields had seen enough. You can’t fool me, she said. “You’re probably some nice Jewish kid from Long Island.”

Fields wasn’t that far off. Simmons’s mother was a Holocaust survivor who raised her only child in Haifa, Israel. When 9-year-old Gene got off the plane in New York in 1958, he saw a billboard with a picture of Santa Claus puffing on a cigarette. Gene thought to himself: Why is that rabbi smoking? An outsider from halfway around the world, Simmons had barely seen television, wasn’t used to paved roads or refrigerators. Unable to speak English, he was taunted by his classmates.

It was one summer day, when the Israeli kid named Gene Klein wandered out to play with the big boys, that Kiss was truly born.

“Ha-low” was about all he could say in English, as he approached a circle of neighborhood kids playing marbles. “Ha-low,” he said.

“What are you, stupid?” the kids laughed, mocking the way he talked. The circle of boys enjoyed themselves, but Klein stuck around. And when they finally let him play—the Queens way, shooting from your knees with one hand, not the standing up two-handed shot he’d learned in Israel—they quickly stopped laughing. He walked away after taking every kid’s marbles, so many of them in his pockets that he was trailing marbles all the way home.

Gene Simmons put those marbles in a Dutch Masters cigar box. He has kept them to this day, as a reminder to himself. Not only will he speak your language better than you, he will teach it to your children. “It reminds me that if anybody makes fun of you, punish them—all the way.”

Simmons has an attitude to the dominant culture common among many an immigrant. He’s an absolute assimilationist—eager to have the natives love him, willing to play their game better than they do. He even ended up teaching their kids English—before Kiss, he was an instructor at PS 75, where he got into trouble making Spider-Man required reading.

But like a lot of immigrants who come with little and make it big, he has a narrow understanding of what others might need to be happy. He sounds like the uncle that tells you being an artist isn’t practical. What seems most old school about Simmons (and Stanley, formerly Stanley Eisen) ultimately isn’t the power chords or macho talk. It’s how little they understand what Kurt Cobain was feeling, or what Scott Weiland is going through now.

But I wonder if there’s something more than a bootstrap ethic here. Perhaps there’s also a survivor’s defense mechanism, relayed to him by his mother. His reaction to the critics, to drugs, to whatever gets in his way, is very simple: You are not going to kill me. “Gloria Gaynor forgive me,” he jokes, “I will survive.”

I should have left it at that. When I ask Simmons if there’s a Jewish sensibility at work in Kiss, I’m thinking of Neil Bogatz crooning his heart out at Grossinger’s, or the early satire of MAD Magazine. Simmons, naturally, has his own agenda.

“If the gentiles of the world are willing to worship a Jew, I want them to worship me, too. I figure, what the fuck does Christ have that I don’t have? I’m much better looking, and I won’t keep changing my mind—first he dies, then he comes back, then he goes away again. It’s a perfect Jewish scenario.”

Things had a way of happening to Kiss, strange things that added to their myth as they clarified the band’s meaning. Like the time In 1983 when an Argentine radical faction vowed to blow them up if they set one platformed boot in the country. That made it official: The band had become a symbol of American power more perfect than any U.S. president. Though the threat must have scared them (they skipped Argentina that tour), it must have flattered them, too.

Or like the time in the late ’70s when a gang of Japanese girls wearing Nazi uniforms chased them through a Tokyo department store—fans everywhere joined the Kiss Army, but maybe these girls were taking it a little too far. Or the time Paul Lynde censored Gene’s tongue on Lynde’s 1976 Halloween special. Possibly the band should have more to show for their 22 years in the studio than an invaluable greatest-hits album, but they accomplished something far more world-historic outside the studio: They changed the nature of stardom.

Tribute was everywhere, all publicity truly good. Religious pamphlets condemned them anonymously on street corners; a gritty gay-porn tape titled Performance featured a studly stud made up to look like Simmons. Kiss were living a new kind of life, not quite Vegas (they were too funny for Vegas; they enjoyed life too much) and not quite rock’n’roll. They recorded a handful of great songs—”Deuce,” “Rock and Roll All Nite,” “Black Diamond,” “Shout It Out Loud”—and far more that are dumb as rubber doughnuts. But who needs rock critics when Paul Lynde is offering some twisted, yet ultimate, kind of respect?

Most of all, Kiss recast what it meant to rock. A Kiss fan clarified this to me by distinguishing between his favorite group and the best group. Kiss became a lot of people’s favorites not because Paul was the best singer, but because everything—the costumes, the cherry bombs ringing in your ear, the Kiss model–Chevy van—the whole damned package rocked.

In Kiss’s music there are no place names, no real people, dates, or events to confuse with your own life. The Chevy was your lunar module, and you checked your own life at the Coliseum door. Rock became another world. It ceased being a release, and became a perfect escape.

It also created an undying legion of fans for whom this summer tour proves Kiss’s superpowers. You can see it in the eyes of Jonathan Fenno, huge, staring gray circles, as he plays the Bally’s Kiss pinball machine. He’s guiding a ball through a gate with Simmons’s face painted on; when the game ends, the machine plays a tinny version of “Shout It Out Loud” and Fenno blinks.

It’s hard to imagine a fan more passionate than Fenno. He knows details of Kiss’s 1977 Japanese tour better than the band. In 1978 he traded Princess Leia, Ben Kenobi, and Luke Skywalker action figures for Gene’s solo record, and with that his future was clear.

Fenno lays back on his bed in his San Francisco apartment, his feet up on the pinball machine, surrounded by Kiss memorabilia. On a counter sit a stack of fanzines Simmons published as a teenager; nearby is a Peter Criss vest from the Love Gun tour and Paul Stanley’s “Firehouse” hat. He’s got guitar picks from every single Kiss tour, and above him loom giant promotional ads for the solo albums. Several times he reminds me that Criss calls him “kid.”

Fenno can’t imagine a global catastrophe that would keep him from attending the Detroit show. “I’ll be sitting on the sixth row with Depends on,” he exclaims. “I’m going to have an oxygen mask and I’m going to have an IV in my arm just to keep me alive, because otherwise I’ll die!”

As he talks, a few more reasonable looking people come up the stairs and join the conversation. They, too, are Kiss fanatics, two of them musicians in Destroyer, Fenno’s Kiss tribute band. Fenno plays the part of Ace. The task of being Destroyer’s Gene falls to 21-year-old Erik James. Never, ever does James ask, “What’s my motivation?”

“The thing that makes me feel like Gene is the looks on people’s faces after I spit blood,” says James. “I see them amazed and sometimes disgusted.”

“One time when Erik was spitting blood, me and Jonathan were at the side of the stage watching him,” says the man whose autograph reads “John Stockwell (Paul Stanley from Destroyer).” “It looked so authentic,” Stockwell says, “we both started crying.”

“When you talk to people who aren’t fans,” says Penny Magalong, “they look at you like you’re a total freak. I don’t think anyone else can understand. It’s almost like a marriage.” Her husband, another fan, nods in agreement. These aren’t the lovable brain-fried teens of Dazed and Confused; Magalong is 29, and works for a Bay Area health-care provider. They admire a band that has stuck it out these many years, working rock’s back roads and state fairs. And they’re stoked that Kiss are getting together again because it validates their devotion—they’ve been clamoring for a reunion tour for years, and finally their prayers have been answered.

“Every day, at every Kiss convention, that was the first question they were always asked: ‘When are you gonna get back together?’ ” says Magalong. “They wanted to give it to us. I think they really want to do it.”

John Stockwell has a prediction. “They will do this for two or three years and that’ll be it. Because they will be eligible for the Rock and Rock Hall of Fame in 1999. And there will be no better way than to go out on top.” The rest of the room nods in agreement. They hold out hope that when Kiss get to the top, they’re bringing all their friends with them.

Psychiatrists call it the primal scene: the tremulous emotional upheaval of a child watching his parents make love. I have never observed this fateful scene, but I’ve seen something equally wrenching. I have seen the members of Kiss in flagrante delicto—i.e., without their makeup—one April evening, bowling.

It’s lead guitarist Ace Frehley’s birthday. And as part of Gene and Paul’s ongoing efforts to make Ace and Peter feel part of the family again, a surprise party is being thrown.

The potential for hard feelings is still there. The four are diplomatic around each other, and make a show of their mutual attentiveness. They’ve hammered out a contract that, they hope, leaves nothing to argue over.

“The rules of this game are very simple,” Simmons explains a few days later. “To get back into Kiss you have to do what we say.” We is Stanley and Simmons. One rumor has we reaping 80 percent of tour profits to Criss and Frehley’s 20 percent, but we don’t like to talk about money. “There are four members in the band, and everybody’s in the same car,” explains Simmons. “But just by design, two guys have to be in front and two guys in the back.”

He bowls a frame, then starts working this Studio City room. Simmons’s friends in Helmet are here, and the band’s guitarist, Page Hamilton, corners him, begging him to let Helmet take the tour-opening slot Stone Temple Pilots have jeopardized. “We really want to go on tour with you,” Hamilton exclaims. “Fuck punk rock! Fuck punk rock!”

Simmons is noncommittal. As he takes his turn again, I make the startling discovery that in order to grip a bowling ball, one must make the Satanic sign of the beast, pinkie and index fingers extended. Kiss were once picketed by Christian fundamentalists who spread a rumor that the name stood for Knights In Satan’s Service. Today another rumor is born: that Gene Simmons sold his soul to master the 7-10 split.

It’s clear from the way the pins cringe in submission why they call Simmons the God of Thunder. And Stanley, too, shows a steady hand as he mows down frame after frame.

Meanwhile, Frehley sits a little bit apart, looking lost, smiling sheepishly. He’s always been the moodiest, most down-to-earth person in the band, never as comfortable in the spotlight as the two guys in the front seat. When it’s his turn to bowl, Frehley slumps up to the line and hurls the ball sideways with two hands. It’s not worth a deuce.

Frehley grew up in the Bronx, his childhood more violent in the telling than Stanley’s and Simmons’s. He was a member of the Ducky Boys street gang. If you saw A Bronx Tale, you saw his high school, where race rumbles were common.

“Half of my friends are dead now or OD’d,” says Frehley. “My best friend hung himself at Rikers Island. It was a rocky road—but music got me away from those people.”

In the wild world of Kiss, Frehley had earned a reputation as the wildest. He came back to a hotel room in France once with a model and a bottle of champagne, and passed out still in makeup; when he came to, his eyes were swollen shut, a reaction to the silver in the cosmetics. Inquire about the time he wrecked his car, and he’ll ask you to be more specific. Which head trauma? Was that the Delorean?

“In my 20s, I didn’t think I was gonna live to be 30,” Frehley says a few days after his birthday. “I was surprised I hit 40—and now I’ve hit 45, which is mind-boggling.”

Frehley was the only Kiss member to score a hit from the 1978 solo albums, the punchy “New York Groove.” Emboldened by success, not getting as much attention as Simmons and Stanley, Frehley left the band in 1983. He toured with his own outfit, Frehley’s Comet. You might as well have called them “Kohoutek” for all the people who saw them.

“There were some hard feelings when I left. I had some substance-abuse problems at that point in my life. I wasn’t thinking straight. I was getting very suicidal, frustrated, the syndrome of too much too soon. The success of my solo album…that kind of planted the seed: ‘Hey, maybe I can do it on my own.’ “

It took Frehley a long while to realize that in the time it took him to sleep off last night’s bender, Simmons and Stanley would have iced a half-dozen interviews. “I’ll be honest with you,” he says softly, like someone just getting over an operation. “Once I left, it was a lot more of a rocky road than I thought it was gonna be. I didn’t realize how much I depended on Paul and Gene and Peter.”

A few days later, drummer Peter Criss tells a similar story. It was the gang life that provided him with girls and fine clothes and respect, and he might have stayed with it except for the violence. The irony for him and Frehley, of course, is that they found everything in Kiss that they’d experienced in gangs—including, ultimately, the self-destruction.

Tired of getting beat up in his Brooklyn neighborhood, Criss joined the Phantom Lords. He’d make zip guns from car antennas and cap pistols and sell them for $5 a pop, until his grandmother caught him and broke a broomstick over his head.

Criss worked his way up in the gang and became war counsel, the man responsible for deciding which weapons would be used at the rumble. He liked the life, but then some guy came after him with a meat cleaver.

Being the oldest person in Kiss posed its own problems; Criss had been in more bands than the others, and came to feel, like Frehley, that Stanley and Simmons were bogarting the attention. That was especially true after “Beth,” which Criss sang and cowrote, became Kiss’s biggest hit, in 1976.

He drank hard, threw tantrums. Maybe one wasted night in Tokyo can stand in for all the others. Criss had locked his hotel room door, stripped naked, and left a trail of clothes leading up to an open window. When the band broke down the door, they feared the worst until his giggles from under the bed gave him away.

Criss would be the first to tell you life hasn’t always been easy since Kiss. His marriage fell apart, he lost a 20-room home, his own records tanked. About the only time his name surfaced after he was fired was in the mid-’80s, when a homeless man claiming to be Criss fooled a number of reporters and celebrities. The real Criss went on Donahue to get his name back—and was ambushed by a woman in the audience who alleged that she had an affair with him while his wife was having a baby.

Right now, the real Criss is in full costume, eating salad while a photographer sets up. Speaking In a thick Brooklynese, the 48-year-old Criss could play a goombah in a Scorsese movie, if Scorsese ever filmed Cats. He seems almost embarrassingly glad to be back in the band. “I never felt happier in my life. I wish I would have felt this way when I was younger,” he says. “You think it’s gonna go on forever, and then you lose it again. Nobody’s gonna take It away from me now.”

Now that he’s got the cat’s superpowers back, it’s clear how much they mean to him. “I’m really cute,” he begins. “There’s a cuteness, but then there’s a power, like don’t fuck with me. You fuck me and I’ll kill ya.” Suddenly, the war counsel is in the room, painted and ready for battle.

“The other Peter—he’s not here now. This is a stronger character. And the other three guys have to be with me; they are my other powers. I couldn’t be as strong without the others around.”

Long gone are the days when the record company had a bottle of champagne, an eighth of coke, and a bag of Quaaludes waiting in his hotel room. But if the ’70s has taken a physical toll, you wouldn’t know it when Criss is in makeup. When he’s in character, he doesn’t quite recognize himself.

“Look at this face,” he laughs. “That’s a gift from God. I didn’t come up with this face. I often ask myself, ‘Where did that come from?’ I could have been a fox, or a bear, or—but this is me! For some reason I feel so comfortable in this.”

He looks comfortable, too, like he’s ready to lick up some milk. “I’m serious about it. It’s not just a gimmick. Fuck you, gimmick!” He sounds ready to put my head in a vise.

“This is a reality, this is what it is, this is what we are. And I know that more now than I’ve ever known it. No gimmick. This is Kiss, and it’s a wonderful thing, man.”