Florida doesn’t get enough credit for its alchemical properties.

The state’s salt, sea and ungodly heat have a way of boiling off the excess material of things, turning out a newer and truer object. Spanish settlers came to the state almost five centuries ago. They built homes in the swamps and came out rednecks on the other side. Local yokels have morphed into something more than the subject of town gossip as their exploits became folklore, a distillation of the American personality into nothing but id. Chicken tenders on a sub took root in the state, elevating itself from a stoner sandwich to a pseudo-religion.

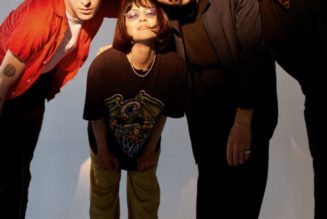

In that regard, Palm Coast’s Home Is Where might be the most Floridian band running. The 4-piece emo outfit spun gold on their rapid-fire debut I Became Birds, throwing horn arrangements, triumphant, pit-opening guitar and a fair bit of harmonica into the crucible to cook up one of the most arresting and interesting rock albums in recent memory. Train-hopping folk instrumentation and vocalist Brandon MacDonald’s carnival bark melt with elements of hardcore and Midwest emo to conjure something entirely new.

That the group would be so adept at calling up sounds ex nihilo is not surprising. The album is about creating a new self, as it was written over a half-decade where MacDonald was coming to grips with their gender identity. SPIN spoke with MacDonald recently in a wide-ranging chat about the album, transitioning, Scientology horror stories and what it means to “become birds.”

SPIN: When did you start working on I Became Birds?

Brandon MacDonald: Around this time, spring of 2012. I had this idea for some kind of grand concept album after I heard In the Aeroplane Over the Sea for the first time. I’m sure you have an idea of what that album does to a very confused and unhappy 16-year-old person… I have a few screws loose up in the old noggin, and I was in and out of mental hospitals around the time. I was having really vivid dreams about Edie Sedgwick visiting me in my dreams to give me guidance or something.

[The album] was about all the things that happened in those dreams. When I decided to write what would be the next record, I wanted to make a rock opera about Rolf from Ed, Edd n Eddy, like a fish out of water, somebody who’s there and wants to be there but also doesn’t feel like they belong.

[This was also] when my gender struggles started really hitting me full force. My identity just became harder and harder to ignore. I’d been ignoring it up until then because I was afraid of ending back in the mental hospital. I felt like if I unraveled that, as emotionally immature as I was, I felt like I would’ve just ended back in there or worse if I just sat down and tackled it. It got to a point where it was coming out subconsciously, in the lyrics that I was writing.

At one point, I watched the first season of Pose on Netflix and I just started crying because I was like, “I want to be that. That’s what I feel like constantly.” That opened up a box of snakes that just wouldn’t slither away.

What does that have to do with L. Ron Hubbard?

When I started writing [I Became Birds], I was really into Beck, specifically One Foot in the Grave… I stumbled upon an interview where he’s talking about how he was raised in Scientology, and I just thought this dude who I admire and really care about was raised up in this horrible organization that tormented people, tore families apart, and yet he found something good out of it. I equated the idea after getting I was watching Scientology escape stories and equated the idea of leaving a cult to discovering who you really are. People born and raised in the church specifically talked about how they were just assigned a job to do and they did it without question until one day they couldn’t do it anymore, and that’s what I felt when it came to my gender. It felt like I was leaving a cult.

That story of discovery isn’t super apparent on first listen. Is that liberatory feeling what “I Became Birds” means?

I feel like in the age of complete immediacy, [the album] feels cryptic, but for me, it’s easy to figure out if you just sit down and really think about it for a second. If you can’t figure out what I’m going for, which I don’t think many people could, I think you can find something for yourself in there, whether or not you’re having a gender crisis. You could be a cis dude who’s totally been fine with whatever they were assigned and still find something in that record to “become birds.”

So, “birds” is what you need to be. For me, it was coming out and living my life as a trans person. For anybody else, it could literally be just becoming happy, or just content or comfortable, or sober. “Birds” is whatever goal that you have that is a completely necessary desire. It’s not just like, “Oh yeah, I got this really sweet 40-inch TV,” or some shit. It’s something that [you’re] hoping for, and yeah, so that’s birds.

You kind of became the unofficial ambassador of fifth-wave emo. If you had to give a definition of the fifth wave, what would you say? What sets this era apart from, say, the emo revival?

Fifth wave feels like to emo what the ’60s felt like to psychedelic music. Like there’s a lot of possibilities here, there’s not a lot of stuff like it that came before. It’s still developing too, and it’s really still in its infancy, so whatever I say, there’s really not too much of a chance that it will hold up in the future. God knows what’s going to happen next.

I see it as something really beautiful and hopeful. That’s all I can really say. There’s not one sound that’s unifying it. There is no atmo-emo clique where these atmospheric emo bands are talking about how airy they want their guitar tone to sound or anything like that, it’s just these patterns I’ve noticed, and when I notice patterns, my brain clicks because of those screws that are loose.

The revival was like a masquerading of bones of what the second wave [of emo] was, in a good way. I enjoy it. But the nail in the coffin [for the revival] for me was American Football coming back. This band that everybody and their mother was inspired by. It’s like when you’re reviving a human being, once they’re alive you don’t keep doing chest compressions, you let them go.