The collapse is nigh. Everything means nothing. Superstructures blot out the sky. People shout invectives through N95s across divisions of understanding. The pandemic has rendered even the most quotidian errands potentially perilous. On top of it all, we are flattened to an austere mode of living, a kind that provides a springboard for the musings of T. Hardy Morris, the psych-folk singer-songwriter intent on finding some traces of hope within modern meaninglessness, now exacerbated by conditions of lockdown.

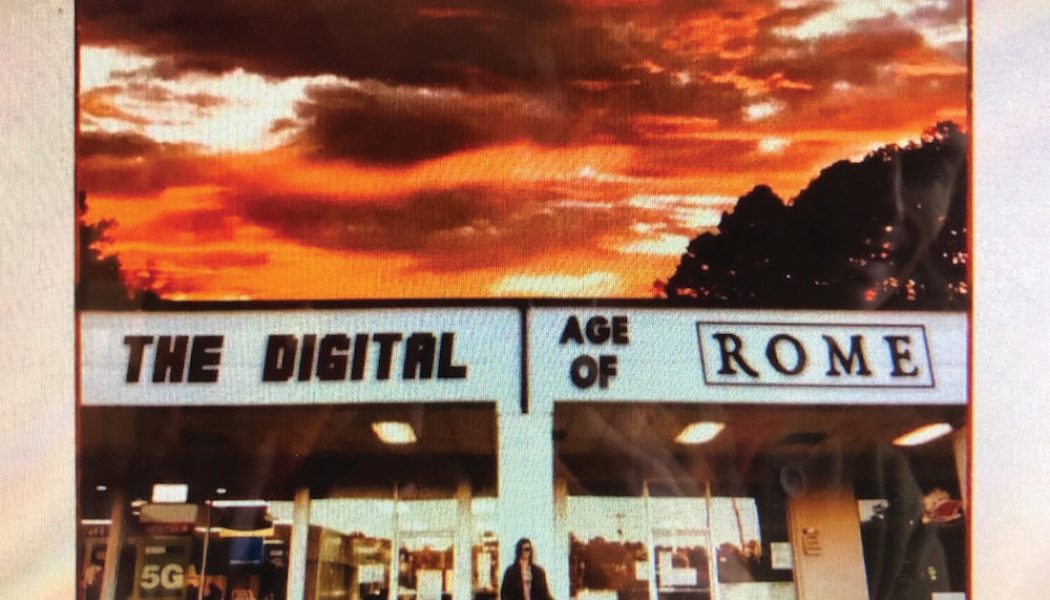

Despairingly singing of the contemporary state of the world and of its sorrows and contradictions, Morris has a heartfelt incisiveness unchecked by vanity, one that gushes without fetters. And so, casting himself as the world’s mirror, his latest LP, The Digital Age of Rome, can be pretty broody at times, but the music to which it’s set belies its lyrical woe. It’s psychedelic and somewhat poppy and singalong – a stark deviation from his previous folksier, traditional-leaning output both solo and with his former band, Dead Confederate, and its utility of modern sonics reflects that. He told SPIN over the phone that he decided to ditch the erstwhile sounds for a new one, to “sound like modernity, a little more up-to-date with where we are…it’ll still be pleasing, but I added some uneasiness…some discomfort.”

It’s meant to be transformative more than it’s meant to be nihilistic and it’s laced by a wish to preclude our cycling back into such a calamitous time again. Hardy was adamant to mention that “it’s not all doom and gloom, the whole album. Hopefully the next album will be nothing but sunshine and rainbows.”

While we hope those better days are up next in the cosmic queue, we spoke to Morris about the less-than-lovely ones in which we find ourselves now.

SPIN: The new record seems loosely conceptual. Is there a premise to the album?

T. Hardy Morris: I guess that kind of what happened was I had a bunch of songs and was planning to go into the studio and that was back in early of last year and then COVID hit and so it obviously hit the brakes on everything and I had demos of all that stuff and that’s what I thought was going to be the album. But then after COVID hit, like everyone else, you kind of reevaluate a lot of things just by the nature of what was going on. I think everybody was just like “what’s this?” and “what does this mean?” and “what is that?” So, I wrote a bunch more songs and it kind of morphed. I mean, the entire album isn’t in that realm of what-is-the-world-worth? But there definitely is some of that. “The Digital Age of Rome” felt like the centerpiece of it.

You could have settled for simply: The Digital Age. Why did you include Rome in there? What does Rome represent for the album?

Well, the first democracy, seemingly sound and strong, was well-established and ran and worked for centuries—centuries longer than we’ve been here. But it did falter, and failed, obviously, and burn. So that’s the parallel: Technology doesn’t necessarily equal progress, you know? And so, I think if you could keep that in mind, you look at all this as like yeah you can do that but is it good? You can scroll around and see people you knew from high school and see their kids but, you’re in the real world. Like, are you really supposed to know what their kids look like? Does it matter? They live in Ohio. Who cares? I don’t know—like I say, the whole COVID thing makes you reevaluate things; So, I wrote some songs about it. “The Digital Age of Rome” felt especially like not only did it speak to that moment we were living through, but it speaks to what is going to continue coming at us. And I didn’t really want it to be super concept-y, but that’s just kind of what happened.

The tracks like “Shopping Center Sunset,” “First World Problems” all seem like critiques on modern life. Or is there a sort of socio-political critique behind them?

I would say more the former. [They’re] like social critiques or just critiques on modern [life], but more on materialism. “Shopping Center Sunsets” is more of an imagining of materialism and the dystopia that the world inherits from that materialism. We drive by empty shopping centers [that are] seemingly empty and we act like there’s nothing there. But really there’s parking lots and lights and shopping carts and pavement and trash and just a bunch of shit that is there until our grandkids are dead—all that shit will be there, which was once a forest, you know. You look at that kind of stuff and you’re like, “we don’t know what we’re doing.”

You know, there’s a shopping center not far from my house – where the song kind of came from. You drive in there and in the evenings, it’s the best place in town to see the sunset. It’s amazing. But the foreground is just… Hell. I’m sure it was once filled with all these stores that are seemingly full of beautiful things, but then it’s just going to go away and the sunset’s going to continue to beat it every time. Nothing can out-glitz a beautiful sunset. We build all this shit to compete for people’s attention, but the sunset’s going to win for another 2 billion years.

So, yeah, there’s a bleakness to the album…

Yeah, it unintentionally turned into that. After it was all done, I was stoked on everything and then I go to listen to the masters and I’m like, “man, this is a downer” [Laughs]. But whatever, that’s just what happened.

I actually stumbled on this thought of how people are always talking about living in the present moment. And then you look out, look around and things are so – like we’re saying – you know, empty shopping centers and materialistic Hell everywhere. And it’s like, well, if the present circumstances threaten the future – which our present circumstances certainly do, environmentally – then doesn’t that just essentially annihilate the present moment? It’s a horrible thought. But it’s also kind of a reality. So, you kind of get caught in the cycle of like “oh, let’s live in the present moment,” but this is not good. So, it sucks man, ’cause I’ve got kids and shit so I try not to dwell on that or think that way. But that’s what art and music is for, to kind of expel some of that. So, that’s kind of why the record turned out the way it did.

The last track is “Just Pretend Everything Is Fine” and because it’s positioned at the end, it’s almost like an anti-call-to-action. Why end on that note?

Oh man, it’s just like that final… Well, I like that the song doesn’t sound necessarily bleak, though lyrically it kind of is. And, it’s what we do a lot of the time—just pretend everything’s fine. So, I wanted to put it at the end as one final shrug, to be like, “Oh well, I said all this, but it’s probably not going to mean a damn thing.” It’s just going to be: Scroll on, 18-Wheeler.

Do you think that’s a product of the time we live in? That’s our last resort?

[Laughs.] I hope not. But we’re going to have to do a lot more coming together. I don’t truly feel like we’re on the cusp of complete disaster tomorrow. But we could be. But it could be a good disaster. Maybe it’ll just be like some economic collapse that hopefully only hurts billionaires and millionaires. You know, maybe it’ll be something like that—upper-level economic collapse, that would be fine. But I think the calamities are coming. Hopefully, they just affect those that have the means to navigate around them or we just learn to live in a simpler way.

Yeah, because, if you think about it, I mean all these issues that are coming is only because of the gigantic chasm of divide in our country. That’s just the reality. We’re all in the same storm, but we’re in different boats. If we’re all in the same storm, but in the same boat, then we can all figure it out a little easier.

![John Digweed on the Intricacies of a VR Festival Performance and the Impact of COVID-19 on Dance Music [Interview]](https://www.wazupnaija.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/john-digweed-on-the-intricacies-of-a-vr-festival-performance-and-the-impact-of-covid-19-on-dance-music-interview-327x219.jpg)

![Watch ASADI Perform a Persian Trap Music Set Live from a Hilltop Overlooking Las Vegas [Q&A]](https://www.wazupnaija.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/watch-asadi-perform-a-persian-trap-music-set-live-from-a-hilltop-overlooking-las-vegas-qa-327x219.jpg)

![“Future Rave” Pioneers David Guetta and MORTEN Claim Their Territory With “New Rave” EP [Exclusive Interview]](https://www.wazupnaija.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/future-rave-pioneers-david-guetta-and-morten-claim-their-territory-with-new-rave-ep-exclusive-interview-327x219.png)