This article was originally published in the December 1988 issue of SPIN. We’re republishing this on the 15th anniversary of Owens’ death.

Buck Owens has spent the last few years looking after business in Bakersfield, California, back again where his career began. When country music went slick in the ’70s, Buck let it alone—and for the last decade or so, he’s been remembered by most people as the grinning face they saw when they clicked the channel past the “Hee-Haw” reruns.

<!– // Brid Player Singles.

var _bp = _bp||[]; _bp.push({ “div”: “Brid_10143537”, “obj”: {“id”:”25115″,”width”:”480″,”height”:”270″,”playlist”:”10315″,”inviewBottomOffset”:”105px”} }); –>

There was a time, through most of the ’60s, when Buck Owens was the most consistent hit-maker in country, when he and the Buckaroos were the hottest live act in the field, when the Beatles’ cover version of his “Act Naturally” hit the pop charts right alongside the Buckaroos’ “I’ve Got a Tiger by the Tail.” The Bakersfield Sound, as represented by Buck Owens and Merle Haggard, offered a powerful alternative to the mass-produced Nashville Sound, with the Bakersfield boys representing the honky-tonk tradition against the threat of homogenization that would nearly destroy the music in the ’70s.

Like Merle Haggard, Buck Owens was a Southwesterner, born in tough circumstances, and raised around hard work, hot music, and cool bars. The Buckaroos, with Don Rich playing guitar, fiddle, and singing those unmistakable harmonies, were the best performers in country, and the music he made was unfailingly commercial—”Together Again,” “Love’s Gonna Live Here,” “Foolin’ Around,” “Cryin’ Time,” “Above and Beyond,” “My Heart Skips a Beat,” and a whole bunch more are still shuffling ‘em around dance floors tonight.

Which doesn’t mean Buck wasn’t an innovator in his own way. Back in 1965, when country music conservatives were making concerned clucking noises about the way the Buckaroos’ records were getting over in the world of rock’n’roll, Buck made a special effort at calming them down, taking out full-page ads in the trade publications to declare his undying loyalty to the music. “I shall sing no song that is not a country song,” he wrote, “and I shall not forget it.” His next single, with the Buckaroos banging away full blast, was Chuck Berry’s “Memphis.”

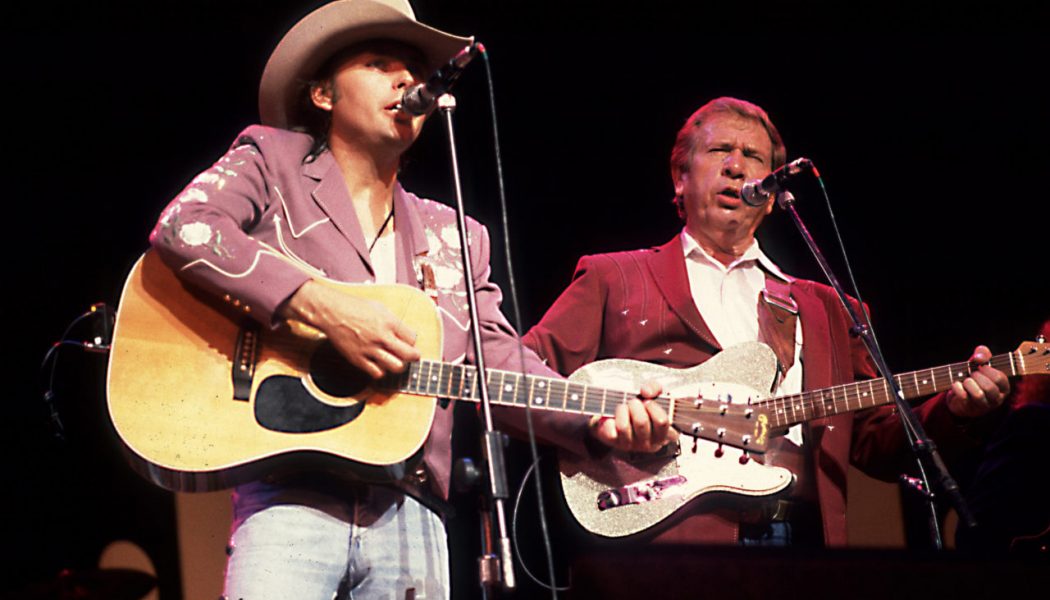

Dwight Yoakam, a devoted acolyte of the Bakersfield Sound, was instrumental in luring Buck out of his self-imposed retirement from music. Collaborating on a single with Dwight called “The Streets of Bakersfield,” Buck is also releasing a new album of some re-recorded early hits entitled Hot Dog. Sitting around a hotel room in Nashville, Dwight had a few questions he wanted to ask.

DWIGHT YOAKAM: When do you first remember hearing a song that had an impact on you and who was the artist?

BUCK OWENS: You know, the first music that I remember hearing, I must have been about four or five years old. It was in Dallas and it was the Light Crust Dough Boys. I lived in Texas but I listened to it over, I believe, WFAA radio. And I liked that and it was kind of Bob Wills-y, you know? Western swing. Then later on when I went to Arizona we had an old radio that my daddy took out of a car. I don’t know if it was ever in the car, but it was a car radio and he’d take the battery out of the car—we only went to town once a week—he’d take the battery out of the car and that was our entertainment. We’d listen to those high-powered Mexican stations on the border. They played Bill Monroe and Charlie Monroe, and they played Wayne Rainey and Lonnie Glossen. It was on those big transcription things.

DWIGHT: Do you think people were aware that Bob Wills had had such a profound impact then? Certainly Bob Wills is known for Western swing, but people don’t realize that that was dance music—it was dance hall music. Do you feel that perhaps the greatest affinity you have to him is that you created dance music also?

BUCK: Well, yeah. You know, when you live in the Southwest there wasn’t no places to play. The only places you had to play was the honky-tonks and people danced in the honky-tonks. There was no school houses to play, you know. If you didn’t play for dancing, you didn’t play.

The only role model that I had really in those days was Bob Wills. I saw him many, many times. He used to play Bakersfield once a week—he’d play in the big old dance halls. One of the things that Bob Wills always had that influenced me more than anything else—he always had a great band. And he had several great guitar players, you know. I remember some of them—Junior Bernard, and some of those guys that could really play. I used to go for the guitar playing. But I went for the whole thing. Bob Wills, he was my hero.

DWIGHT: At what point did you move from Mesa [Arizona] to Bakersfield?

BUCK: After I’d turned 21 in 1951.

DWIGHT: Based on what? Hearing that there was music going on there, or were you really looking just for work?

BUCK: I’d been there a lot of times. There was a lot of fruit there and a lot of cotton and a lot of work, for a field worker. And I had a lot of relatives there also. Two of my uncles played the guitar a little bit and there’s always music around where there was a bunch of country folks. They’d just strike up at the house. So I went on out there when I was 21 years old. I’d run away from home when I was 15, went out there and then came back and then I’d go back out there—I’d been there several times. But there’s a pretty strict rule in those days, if you weren’t 21 not only could you not perform, you couldn’t be in there [honky-tonks] either. So, as soon as I turned 21 I headed back out there.

I got a job, right after I first went there at a honky-tonk—a big, big honky-tonk, held about 500 people—called the Blackboard. I worked there a total of 7 years. Commuted to L.A. and back and a few times to Nashville. But I got to learn my trade. The important thing was there that I got to play with a lot of different people. I made enough money to support my family and meet my obligations and get to do what I wanted to do, man, what I dreamed. We played for dancing, and we played tangos and rumbas and sambas and mambos, and I didn’t know the differences. But I learned after a while; I learned how to play some of those things that were good. It was just good all around experience for me.

DWIGHT: When did you first play the guitar?

BUCK: You know, Dwight, my mother taught me the first chords on the guitar when I was probably nine or ten years old. An old Regal guitar.

DWIGHT: Regal?

BUCK: Yeah, I remember the name of it because I never saw another one.

DWIGHT: Mine was a Kay, and then I broke it and I had a Silvertone.

BUCK: Same thing with the strings about—

DWIGHT: Silvertone was way up.

BUCK: Yeah.

DWIGHT: Bleed—your fingers’d bleed.

BUCK: Yeah, I remember that.

DWIGHT: I want to ask you to talk about “Hee-Haw” a little bit.

BUCK: Okay.

DWIGHT: I guess I should ask what initiated the concept for that show and then what brought you into it?

BUCK: I didn’t know the name of the show when the guy asked me about doing a country-type “Laugh-In” show.

DWIGHT: So it was a country counterpoint to “Laugh-In.” Putting this in context, people perhaps don’t remember that at the time for a country artist to be given the opportunity to host his own network TV show was something that you kinda didn’t look twice at. You didn’t look that mule in the mouth. Right?

BUCK: Unbelievable, because they had—you gotta remember that for many people that was a dream, far-off dream for somebody. In May they said they had the money to cut the show, and in July of ’69 “Hee-Haw” went on CBS. And of course then they took it off. It was on network for about a year and a half, if I remember right, maybe two years and a half. Maybe two years. Then whenever they took it off, they took off at the same time too things like Lawrence Welk and they took off, you know, Mr. Haney—

DWIGHT: Oh, “Green Acres.”

BUCK: I remember what the guy said he was going to do to the network; he said he was going to “deruralize” it. He took off “Beverly Hillbillies.”

DWIGHT: Those were all CBS shows at the time?

BUCK: Well, not the Lawrence Welk show, but yeah. It seemed like the networks had all had a meeting and said, “Okay, folks we’re going to take off all this country stuff.”

DWIGHT: You know, I did “Hee-Haw” once, and I tell you, I had fun doing it. Was it fun for you?

BUCK: It was, very much. It was a lot of fun. You’ve got to remember that it went away from the original concept. See, these guys were comedy writers, and they sold their interest in the thing, and it went away from music to more and more comedy. So after a while it had deteriorated to where it must have been 70 percent comedy. Very little music, and they thought less and less of my music.

DWIGHT: With “Hee-Haw” moving further away from music and more into just the one-line comedy gag situation things do you think that you lost contact with your musical audience? With a new, perhaps an on-going musical audience, I want to add.

BUCK: Yeah, I think that’s absolutely correct. I think one of the things that the TV does to you, it just lays you open. I mean, folks, it removes all mystique, because you’re there every week, and they can hear you sing every week, right? And, you know, what happens is like one guy asked me one time, “Did you just sell out for money?” And I said, “Well, maybe we could put it in another way, you know.” And in reality, I never thought of it as that. I thought of it as after a while, you know, a way to get off of the road.

DWIGHT: Well, it certainly served a financial purpose. But I think that’s an unfair assessment. I think you’ve answered probably more accurately that the show just moved away from music—from your music. Your music didn’t necessarily change that drastically in terms of you selling out your music—I think that they just, they moved it away from music.

BUCK: Well, I think they did. And maybe they did it the right way, who knows? But I mean, it’s 20 years now. But when I left the show in ’86, we had left each other, really. I wanted to leave the show at ten years. But the very thought of going out there and trying to pick up $400,000 for two or three weeks work was a tough situation. So, you kind of look at it again and you say, “Well maybe I’ll do one more year.” But I enjoyed doing “Hee-Haw.” I left lots of friends there. “Hee-Haw,” here’s what “Hee-Haw” did: It took a name and a sound and it put a face with it. But you reached the point of diminishing return, after a while. I think some television is great for you; but I sure think too much is deadly. Overexposure’ll kill you.

DWIGHT: Tell me a little bit about you and Merle and the Canadian border and Moose medicine.

BUCK: [Laughs] We had a drummer—you know Merle [Haggard] played bass on that trip—actually it was in Michigan, that’s where it was. We travelled along in this camper and this drummer called Moose was driving along and he gets on the wrong side—it’s a two-lane road and he crosses across a double line, just a little bit, and lo and behold a block away he’s coming face to face with a state trooper. Well, he turns around and stops us, you know, and so he got us all out and searched us. He thought we was a bunch of hunters—we had some guns, but they were just .22s, just target things. So then, he pokes in my pocket. I got a great big wad of money in my pocket but he don’t know it’s money. And he says, “What’s that?” And I says, “Money.” And he says, “Yeah, let me see it.” So, you know, I had on those tight jeans and I reached in my pocket, and he says, “Careful now.” And so I reached out and I show him all this money and so the man, he says, “Don’t nobody move.” He goes back—he calls in—

DWIGHT: Desperate-looking guys that you were.

BUCK: Well, you know, we probably looked pretty bad. We were pretty raunchy. And he goes and he calls in and he comes back and he says, “Okay, maybe you guys ain’t robbers.” He goes searching everywhere and he looks in the glove compartment—now Merle, you know, he’s still on parole at that time, but we got permission for him to leave California. And so he looks through our glove compartment and he runs across this little brown vial that looks like a prescription for medicine and he’s got something—I don’t know if it had any inscription on it or not, but—we’re up here in hunting country now, and so this state trooper, he shakes it and he shakes it and he says—our drummer’s named Moose now, and he’s the one that’s been driving and he’s the one that’s going to get the ticket—he says to Merle, who was sitting there in the front seat, he shakes this at Merle and he says, “What’s that?” And Merle says, “Moose medicine.” Meaning that they were diet pills and they belonged to Moose. And the cop said, “Oh, okay,” and throws them back in the glove compartment. Of course, moose medicine.

DWIGHT: [Laughs] Give them to the moose. A lot of booze in country music at that time but there was also a lot of pills.

BUCK: A lot of diet pills. Mostly it was all diet pills.

DWIGHT: Speed. Stay up. Drive—truckdriver medicine. You know, you touched on something there—there was a lot of booze in country music. There are classic examples—most overt examples are Hank Williams, Senior, and his battle with it. You never really had a problem, never drank really?

BUCK: No. The only time I drink—I never drank very much, but when I drank one time I drank a bottle and a half of wine.

DWIGHT: What happened?

BUCK: I got married. And when I sobered up, I got it annulled.

DWIGHT: Is that the famous one that everybody talks about?

BUCK: You know that’s the famous one.

DWIGHT: Are you still friends?

BUCK: Oh, we’re good friends. Yeah, I had three very successful marriages.

DWIGHT: [Laughs]

BUCK: I ain’t kidding; I look at it that way. And I don’t count that one because, you know, we annulled it. You know, you marry—

DWIGHT: Went to bed for a week and—

BUCK: For two days.

DWIGHT: Two days.

BUCK: Worked out all right. But anyhow, there was more booze then, I think than there is today. You know, I never even saw any “Mary Jauana,” see, I can’t even pronounce it right. I never saw it.

DWIGHT: But the drug thing was just more involved with the booze and, you know, the speed, the bennies.

BUCK: Yeah, that’s the only thing that I ever saw. Only thing I ever saw was diet pills and booze, you know.

DWIGHT: None of the street drugs that were in vogue at the time, like acid and things like that?

BUCK: No.

DWIGHT: Yeah, I’m going to take your advice and stay clear of the wine. Especially the marriage wine. You know, I was going to say, the Beatles were obviously aware of you. Did you ever meet the Beatles?

BUCK: No, I never did. Capitol had set up a meeting for me. The Beatles, they were so hot, man, that the security broke down and so they didn’t come. We was going to meet at some hotel. It was about ’65, before they cut “Act Natural.” They asked if I wanted to meet the Beatles and I said, “Oh, you bet.” And they said, “They like you.”

DWIGHT: What about other rock artists? Did you ever meet the Byrds? Or John Fogerty from Creedence? People you obviously influenced.

BUCK: No, I never got to meet any of those people. I would play sometimes the same places they’d played.

DWIGHT: Like the Fillmore. You played in a lot of the rock’n’roll venues in the ’60s, didn’t you?

BUCK: Yeah, yeah. It was tough sometimes there. A lot of the young people, even then, liked music with a lot of beat.

DWIGHT: What do you think appealed to those audiences and drew them to you musically? I mean, I know what did for me.

BUCK: I think it’s the same thing. I think the honesty and integrity of the music, as well as, you know, the zing. It had a lot of beat to it, a lot of percussion-type zing.

DWIGHT: Recorded with your own band, too. There was always an active band in the recording.

BUCK: Yeah, and it was the same band I toured with. The same as you. The same as Hag. It goes clear back to Bob Wills. I mean, the people that you saw with him was the people that made the records. The people I see with you is the people that made the records and all that. I think that’s what makes a difference between a recording for the industry—see I think a lot of people go in the studio and record for the industry instead of for the people.

DWIGHT: You own all your masters from Capitol Records. When do we the public, the listeners, the fans of yours, maybe look for the opportunity to be able to get a hold of those in stores ever again?

BUCK: When you come up with the money, Dwight.

DWIGHT: Oh, man, now they’re going to print that. And the truth will be known once and for all. About what it takes. Why do you—why are you making music again? You know, you said to me one time you felt like you got in trouble when you started making music for the industry and not for yourself. When did that occur?

BUCK: ’78, ’79, you know, during the pop music craze. And the record companies—once again I don’t blame the record companies for wanting to sell all the product they can sell.

DWIGHT: It’s a business.

BUCK: That’s what it is. But when the crossover thing stopped, I mean, you know, there must have been pandemonium at that time.

DWIGHT: Now who’d you make this record for?

BUCK: Well, I made it for me, I made it for the folks. I made it—you know, I made it to sell. I made it because I thought that’s what the folks would want to see and hear me do. And I researched those songs, I kept tabs on those songs where if I ever recorded again I’d want to do that again.

DWIGHT: But your motivation was…?

BUCK: ‘Cause I enjoyed it. I wanted to do it. Ten years out of the studio and I couldn’t get you to help me at all.

DWIGHT: [Laughing] Well …

BUCK: I’m teasing, I’m teasing.

DWIGHT: You know I love you and I love your music.

BUCK: Yes, I know. I figured I was going to get you to say that one way or another.

DWIGHT: I hope that it is fun for you and I hope the record was fun for you to do. As much fun as it was for you to come in and record “Bakersfield.”

BUCK: Well, you know there’s another thing too, I ought to say—there’s a lot of things, you know. With “Bakersfield” making number one, and that’s lots of fun and—

DWIGHT: Doubles the fun.

BUCK: Well, it sure does.