In 2017, Madonna thought she was moving to Portugal to “be a soccer mom,” but instead, the 61-year-old icon found inspiration for her then-upcoming album, Madame X, thanks to a friend she calls her “musical plug,” Dino d’Santiago. One night, the Cape Verde-born, Lisbon-based singer — who coached Madonna on how to speak Portuguese and sing in Portuguese and Creole — had arranged a concert for her by Batukadeiras Orquesta, a group of female drummers specializing in batuka, a rhythmic call-and-response style created in Cape Verde during the early days of the slave trade. “I’d never seen anything like it, never heard anything like it. So of course, I couldn’t get it out of my head,” says Madonna.

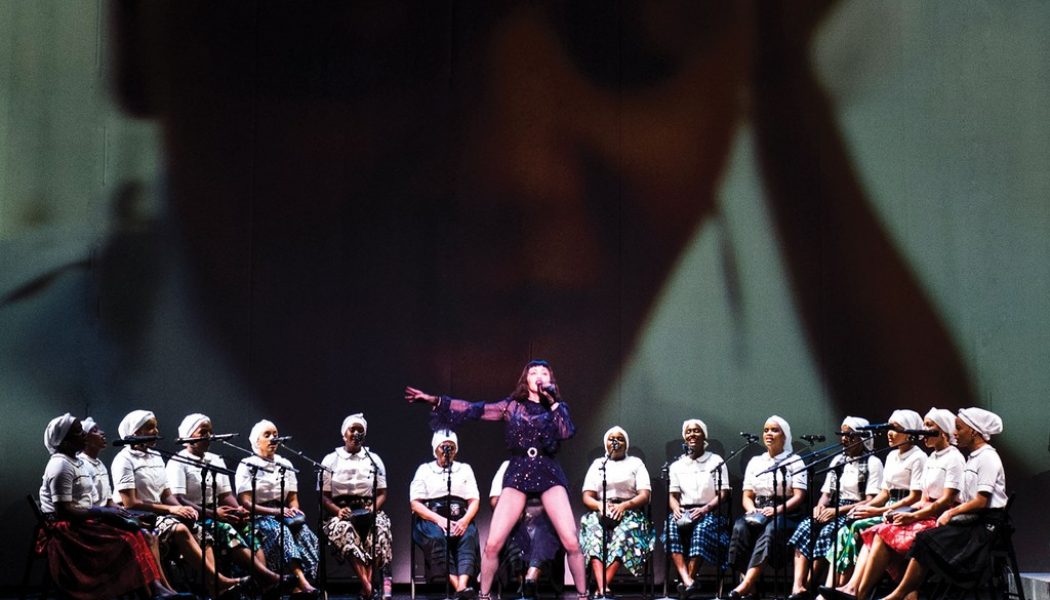

She invited several members of the collective to perform on her album and even brought some to the United States for her intimate Madame X tour that began last September in New York. (Its final two dates were canceled due to the pandemic.) “I thought about [my manager] Guy Oseary’s response to the cost of taking 22 women on the road with us,” says Madonna. (They ended up taking 14.) But her goal was set: “I wanted the audience to get a glimpse of [their] history.”

How did you discover the Orquesta Batukadeiras?

I discovered them once I met Dino d’Santiago, who I call my musical plug. He understood that I wanted to meet musicians and experience all the different traditions and genres that Portugal had to offer. He called me one day and said that he had something very special for me, but he couldn’t tell me what — he just said to show up at this place, at this time. At this point, he had already introduced me to some amazing musicians and brought me to some really cool places, clubs, etc. So, I went to this place — it’s hard to describe — it was like a bar that hadn’t been open in a while. They had opened it expressly for me. There was Abstract art on the wall and a few deer — you know, antlers. It was filled with people. There was a DJ playing electro-African-house music, and a girl singing in a silver lamé suit, and I thought, “Oh this can’t be what he asked me to come here for.” Dino said, “No, this is not what I want you to hear. It’s coming up.” There were some people dancing and eventually the music stopped — the crowds parted and on the other side of the room was a group of women sitting in a semi-circle in chairs, exactly as you saw them on my stage, but there were a lot more of them. They started playing their drums, drums that they held in their laps, and they started beating out these rhythms, and then they started singing and taking turns getting up and dancing. I was drawn to them and we walked closer and closer to them. It was wild – the way they played and the organic way they got up and took turns dancing together and singing solos. I asked Dino what language they were singing in. They were singing in Cape Verdean Creole.

It didn’t seem terribly rehearsed; it seemed like second nature to them. They were like a family, a community of women. I marveled at the age range of the women — from teenage girls to women who looked like they could be grandmothers. It was an amazing, immersive, musical, familial, matriarchal experience. The music was mesmerizing and hypnotizing and it blew me away. We just sat there, stood there, with our mouths hanging open. I’d never seen anything like it before. They were joyous and enthusiastic. There was an abandonment, for lack of a better word.

Afterwards, Dino said, “This style of music is called batuka, this is the Batukadeiras Orquesta.” I met some of the women, not all of them. Dino told me they had to rush out as they all came on buses from far outside of town, especially to play for me. I was extremely moved that they made such an effort and even more so that they were so amazing.

You know, I’d never seen anything like it. I’d never heard anything like it. So of course, I couldn’t get it out of my head. As the days went on, I thought it would be really special to try and collaborate with them and write a song together for my record since so many of my songs were influenced by and/or involving other musicians that I had met in Portugal. So, Dino again approached them and asked them if they would come into the studio and try to experiment, this musical experience, which is a kind of call and response, and they were up for it. Very few of them spoke English, so we had both Dino and another woman who came as a representative and translator.

We all got into the recording studio, the same women and girls, into the only room we could actually record in — we barely fit. I had written some words and I encouraged them to just repeat after me. They start playing their drums, which is a triplet rhythm. Lots of the women sang solos, and I picked out which ones I liked the best, Antonia and Bianina, the women who ended up going on the road with me. What amazed me was how even though we didn’t speak the same language, they repeated precisely not only what I said but also the melody. That’s how our recording went: back and forth and back and forth, until we got it right. They weren’t used to singing into microphones so there was a comical aspect to it. We realized we had to record things separately because I was singing in 4/4 time, and they were playing their txabeta triplet time. In any case, for me it was an amazing experience because they were so open to anything I suggested and to collaborating. They brought their fire and their passion. I explained to them through Dino what the song was about and they loved it because their whole philosophy is about fighting for your rights and empowering women. They were very happy with what I was saying in English.

[embedded content]

After the hours and hours of playing together and singing together, they insisted that we all pray together. That prayer was Amor de Mãe, which is the song that ended up being in the show before they appear on stage, when you see the map. We did that prayer at the end and they all blessed me and wished me well. There was a lot of hugging and tears. I just can’t explain what a positive encounter it was.

I loved the way the song turned out, and after my record was finished, I was putting the Madame X show together and started thinking, “Oh my God wouldn’t it be amazing if I brought the Batukadeiras on stage?” Of course, I thought about Guy Oseary’s response to the cost of taking 22 women on the road with us. We ended up taking 14. Dino then reached out to each and every one of these women to ask if they were interested in going on tour and doing a show with me. It took a while as many of them have families, jobs and school they couldn’t leave, but we welcomed the women who could work things out.

What did it feel like sharing the stage with them every night?

Sharing the stage with them was like an ecstatic experience because I was surrounded by such powerful, passionate women. Having them all around me singing along with all the musicians that I met and work with — I really felt like they were there for the right reason. I felt like they were there to share their message of love and unity and female empowerment. I could feel how proud they were to share this tradition that’s been going on for hundreds of years with the world. It was as if we were feeding off each other’s energy. I wish I would have had all of them, to tell you the truth, because the power of all of them was just so amazing. But the women who did come, I mean from day one of rehearsal: they were always joyful, always positive, always smiling. They had each other’s backs. When one of them was sick, they all gathered around each other. I never saw musicians care for each other so much and support one another so much. They had so much respect for the elderly women in the group. If one was sick they would all insist, “Nope she can’t come to work today. She’s gotta stay home.” And I’d say, “Aww are you sure?” And they would say, “Nope, she’s gotta stay for a whole week, she’s gotta stay home.” It really impressed me how much they loved and supported and cared for one another. It was pretty special, as you don’t see that in our Western world.

There’s clearly pain associated with them, the genesis of their music. Did you talk about that with them?

Dino first told me about the history of their music, that it came from a kind of rebellion. Everything was taken away from them when they were slaves. They had no freedom and what they played on originally came from when they would wash their clothes in the river: They would bunch them up together and turn them into a kind of drum they could play on…eventually that evolved into a leather-covered drum, a piece of leather, stuffed with clothes – with fabric – with a little nozzle at the bottom that they could grasp between their legs when they’re sitting. All they had was their music when they were together. The rule makers, the authorities and slaveowners perceived their music as a form of rebellion – they were not behaving, they were not being quiet, they were not obeying the rules, and they were not being submissive. So, they took their txabeta away and their reaction was: “Okay fine, we’ll play on our legs. We’ll sing anyways; you can’t take our voices away.” I just love that story. That was their spirit, that was their soul and their music is proof that the human spirit cannot be kept down. Dino gave me so many history lessons about Portugal being the birthplace of slavery. When the slave trade first started ships went to the island of Cape Verde, which is on the northern West Coast of Africa. That’s where the slave trade first began.

Knowing their history made their music and these women so important. That they kept that tradition going and that against all odds, they managed to make music, dance, sing, and create joy and happiness in spite of the oppression they were suffering. I wanted this to be known. I wanted the audience to get a glimpse of that history too.

What did you learn from them?

Resilience and the importance of unity — having each other’s backs. You know, that really impressed me a lot. We don’t have that a lot. We’re experiencing that right now obviously, during this time when people are coming together and helping one another, but it’s important to have that spirit at all times. That thought helped me keep going through my show because I was suffering, I was in pain, and they really supported me and really had my back. They were always smiling and supportive, always there for me. It was a real sisterhood. I wanted to show the world that these people exist. We don’t have to live in our separate worlds, fighting against each other, fighting for our place… we can actually work together as a team and be appreciated as a group without cutthroat ambition.

Generally speaking, is there something in African music that’s missing from most Western music?

To me it’s music that has been handed down through the centuries. It comes from the soul of the Earth — it’s connected to nature; it’s connected to community. There’s something organic about it because you can create an instrument out of anything. There’s a soulfulness about it. And a paradox, because there’s sadness and there’s suffering, but then there’s also joy, and the sense that all sorrow and pain can be overcome. And that music is what lifts everybody up. And so to me, that’s the essence of African music that is missing from a lot of Western music that we hear today. It’s not just entertainment. You feel the journey that each of these people have been on, you feel the journey of the past, you feel the journey of their history, of their ancestors. It’s filled with so many layers and complexities.

What other African music or musicians do you draw inspiration or strength from?

I love morna music, which is the music of Cape Verde. It’s the kind of music that Cesária Évora made. To me it’s like the sound of mourning. It’s a kind of sad, melancholic music and again, mesmerizing and heartbreaking but also, like the song “Sodade” that I sang in my show, which Cesária made famous, is about missing. It means missing, to miss something. It’s that longing for your home, that longing for your family that you are no longer with, that longing for a loved one that you are no longer with. It’s about loss, but never being a victim, because even in the song “Sodade,” Cesária says, “Okay, I miss my home and I miss you, and if you write to me, then I’ll write back, and if you miss me, then I’ll miss you too, but if not, then okay.” So, it’s not like, poor pitiful me. There’s strength in the longing, and the loss, if you know what I mean.

What other memorable music experiences have you had in Portuguese-speaking Africa?

One of the musicians that I love and who really moved me and still does wasn’t in my show, but he’s somebody that whenever I go, I always make a point of going to hear him play or I invite him over to my house because we became friends. His name is Kimi Djabate and he’s from Guinea-Bissau. He also sang on one of my songs on my album called “Ciao Bella,” which was only in one of the super deluxe packages of my records. He has an incredible voice and he plays guitar and also plays an instrument called a Balafon. It looks like a xylophone, but it’s a more ancient version of it. When you play with a mallet on these pieces of steel it makes different notes and sounds. When he was growing up, his father and the people in the village were against him playing music as they perceived what he was doing as wrong or negative or maybe connected to witchcraft or something like that. He persisted and eventually was appreciated for his musical gifts and talents and eventually he moved to Lisbon. And now, he has records out. He has an Instagram account — @kimidjabate. He’s a huge talent and he really moves me. And Cesária. Dino d’Santiago – I can’t not mention him also, because you know, he does it all. I mean, he plays, he does morna, he does funaná, he can play samba. He can do anything, he’s an extremely versatile and talented musician.

What is it about him that moves you?

His musicality, his versatility, his passion for what he does, the way he was so excited to introduce me to the Batukadeiras. He was so proud that I could share their music with the world. He’s just a man full of love, you know, and he has his hands in everything. He brought me to a lot of fado clubs as well. He introduced me to a lot of amazing fado singers. He just connected me to everyone musically, he introduced me to Miroca Paris, Carlos Mil-Homens, Jessica Pina, and Celeste Rodrigues – whose great-grandson Gaspar ended up going on the road with me. So, Dino’s responsible for so much – also coached me on how to speak Portuguese and sing in Portuguese and Creole, introduced me to so many different genres and styles of music, brought me to every club there was to go to, brought me to living room sessions, and just connected me to this underground world of music that people don’t know about. I in turn tried to put that into my show and share it with the world. So, he really was my pipeline, my connector — what I call my plug. He did it with so much love, and completely and utterly out of generosity. Usually there’s some manager calling you saying, ‘Okay, so how much, this is what he charges, and this is how many hours he’s gonna work.’

How fluid is the music between Portugal, Brazil and Portuguese-speaking Africa?

Extremely fluid. I mean, it’s the same. There was also an incredible Brazilian pianist named João Ventura, who played piano at the Met Gala for me when I did “Dark Ballet.” He’s a virtuoso pianist who can play anything, classical to pop, and samba. I would go to a small club called Tejo Bar, you could walk in there and hear any of these styles of music with these musicians playing it and it would be as if you were transported back to those countries.

What did you learn musically being immersed in the Portuguese-speaking world?

Well, I learned to sing in Creole and Portuguese. I learned to play the 12-string guitar when I played “Sodade” in my show, and I learned to sing fado. I also learned and understood how limited I am, and how far I have to go as a musician and singer.

Was there any life wisdom you drew from the musicians you met?

To never forget where you come from, and the honesty and purity of those who share what they have learned. It was handed down to them from their ancestors, their families, fellow musicians that they work with. They’re just so open and generous, I really can’t express that more. I’m so used to everyone in America thinking, ‘I’m the best. I’m the best. I’m on top and number one. I’m the greatest. I have the most views. I have the most awards. I’m a King, I’m this, I’m that.’ Everyone’s into titles… labels, and they don’t have that in Portugal. All they want to do is share their love of music and what they know with other people, and it’s really rare and so appreciated, especially now.

The Prime Minister of Cape Verde attended a Madame X show in New York in September. What did you talk about when you met?

Really, the main thing was how proud he was. How proud he was to have his country represented, how he said he was crying tears of joy. He was telling the truth – he was on his feet in the box that he was in from beginning to end. He was just so proud of the Batukadeiras. So proud that all these musicians that I’d met in Lisbon were traveling around the world, sharing what obviously he knows and understands and appreciates, but never in a million years did he imagined that America – people in New York, Los Angeles, Chicago would be experiencing this. I think pride and gratitude was my main takeaway from him.

What kind of response to the album and the tour have you received from other figures across Portuguese-speaking Africa after spotlighting their music in such a huge way?

I think in general all Portuguese people and the music that I represented in my show and on my record were extremely grateful and surprised that I was sharing fado and morna and batuka and funaná with the world. They didn’t expect it. And, well neither did I, but obviously when I moved there, I didn’t expect that I was going to have those musical experiences. I thought I was just going there to watch soccer matches and be a soccer mom.