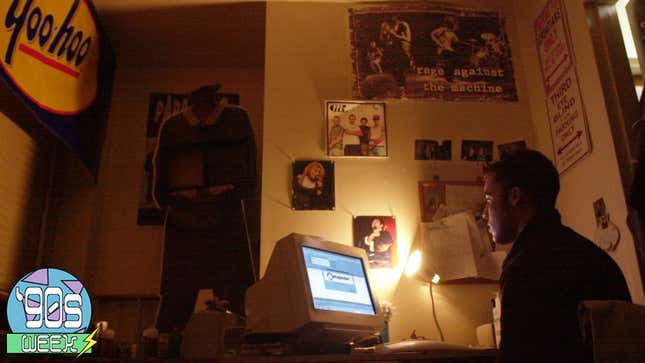

Music from the ‘90s, dominated by the early years of hip hop and gritty grunge counter-culture might not immediately seem like a groundswell for transformative new gadgets and gizmos. However, despite its seemingly unpolished patina, a handful of crucial innovations spanning the decade have arguably done more to foster the current period of relatively cheap, on-demand, DIY musicianship than any other tools prior. An artist in 2023 armed with a MacBook, a decent pair of headphones, and a grand or two to spare can realistically produce a full-length album capable of rivaling a professional product from previous decades.

New tools like Digital Audio Workstations and audio interfaces slowly but surely gave artists the power to produce more work with less while major advances in high-impact technology like the world wide web and the MP3 format meant musicians could share their work with a far wider audience than ever thought possible. Transgressive new products from peer-to-peer file-sharing sites like Napster, meanwhile, paved the way for the streaming era and created an unquenchable consumer attitude for more and more content for less cost.

All combined, these advances in music tools and tech make the ‘90s a watershed decade that set music on a course still being felt today. Like all pivotal advances, each new tool brought its own complex set of tradeoffs for musicians, consumers, and the old guards of music industry titans. Here’s some of the most transformative music tech of the ‘90s and why it matters today.

Possibly the single most crucial piece of technology responsible for transitioning music away from the limited confines of glitzy professional studios and towards everyday artists’ bedrooms was the introduction of the Digital Audio Workstation pioneered by Avid’s Pro Tools.

DAWs, now an industry standard and available in various forms (think GarageBand) to anyone with a laptop, essentially recreate a traditional studio’s tape machine, mixing console, outboard gear, and other parts of a recording studio, and jam them all into a software package. That gives artists and producers the ability to record numerous audio tracks and seamlessly pepper-in effects like reverb, limiters, compression, and EQ previously only really available to studio professionals. When used correctly, musicians can record, mix and master a song from start to finish by themselves in a DAW.

Though a plethora of alternative DAWs exists today, Pro Tools, a multi-track interface designed by a pair of U.C. Berkeley graduates and released in 1991, was the game changer. Originally designed for Macintosh computers, Pro Tools offered artists a four-channel interface with the promise of studio-quality audio all wrapped up in a slick digital interface. DAWs that are now accessible to mass audiences were originally intended for professionals and had a prohibitive $6,000 price point to match.

Like most new music tech, Pro Tools was originally written off by industry traditionalists for the early parts of the decade over fears it was less human or authentic than recording on tape in a traditional studio. That all started to change around halfway through the decade. Artists and producers were drawn to the software for its ease of use and speed for editing. Odelay, released by Beck in 1996 and Ricky Martin’s Livin’ La Vida Loca in 1999 were both reportedly recorded and produced entirely in Pro Tools and served as launching points for the industry, proving once and for all mainstream hit success could and would stem directly from DAWs.

If DAWs fundamentally transformed the way modern music was crafted, a product called Auto-Tune arguably did the most to alter the way modern music sounds. Like Google or Kleenex, Auto-Tune, just one of the numerous tools meant to “correct” the pitch of vocals and instruments, has entrenched itself as a generic noun and become ubiquitous in modern production. Nearly every song you listen to in 2023, whether it seems like it or not, almost certainly uses Auto-Tune or one of its copy-cats.

The inspiration for the tool oddly didn’t come from music at all but from the oil industry. Auto-Tune’s creator, a mathematician and musician named Andy Hildebrand reportedly conjured up the idea for the tools while developing advanced algorithms aimed at mapping underground surfaces for Exxon. In its most basic form, pitch correctors identify particular notes that are considered out of range of a particular key and force them back in line, a process that has some overlap with geological seismographs.

Hildebrand created Auto-Tune with subtlety in mind but more intrepid artists pretty quickly figured out ways to manipulate the new tool to create entirely “new” vocal sounds. By manipulating the speed with which notes are “corrected” to a desired pitch, artists learned to use the Auto-Tune feature to produce odd, robotic-sounding distorted effects. One of the first major examples of this effect presented itself in pop star Cher’s 1998 song Believe. Songwriters for years later would come to use the term “the Cher-Effect” to describe the process of pushing Auto-Tune to its limits. Rapper T-Pain would later take over that mantle with his own Auto-Tune drenched R&B, which he called “Hard&B.”

Auto-Tune and its inspired products have grown and evolved since their ‘90s debut to the point where they are now likely used in the majority of modern recordings, either subtly as a pitch-correcting tool or abstractly as a musical effect. Some artists, inspired by the T-Pain era, now inject Auto-Tune immediately into vocals, or in other cases, applied during live performances. For modern listeners, it’s not a stretch to say the AutoTune sound, if it can be described as such, is simply the baseline for what’s considered “normal” or expected for vocals.

The shift to digital workstations and MP3s fundamentally altered the course of all music, even those less traditionally associated with digitized formats. Amplifier modeling, what some purists originally tried to shrug off as, fake amps, allowed guitars, bassists, and really anyone plugging into an amplifier to bypass the need for physical amps and instead plug directly into a computer for sound.

Pedalboards and amp knobs were replaced by DAW plugins and on-screen sliders. That seemingly small change would have huge implications, essentially giving anyone with a computer the ability to access a world of different musical tones, effects, and amp styles, all at a fraction of the cost of their physical predecessors. Recording directly from a guitar into a DAW also lets musicians bypass the cumbersome and expensive process of micing up studio rooms and painstakingly searching for the ideal way to capture a particular sound in a live room. While that process inevitably loses some of the character that gives a live performance its sense of presence, it simultaneously opened up recording to a near infinitely larger demographic of musicians who couldn’t afford or didn’t have access to recording studios. Amplifier modeling and direct guitar inputs are what make any number of bedroom pop indie bands possible.

The best amplifier modelers of the late ‘90, such as those released by the company Line 6 which offered a few dozen types of simulated tones, seem quaint compared to their modern-day predecessors like the Helix and Kemper Profile which are nearly indistinguishable from the real thing for all but the most trained ears. Many musicians are increasingly turning to these tools for live performances as well, trading out the vans full of amps for the convenience and dependability of precise, preset sounds.

Everyday music listeners may not think much of it now, but the creation of the MP3 file in the late ‘80s and ‘90s may have played one of the single most important roles in widening music distribution for mass consumption of any single new technological innovation to date.

MP3 is actually an abbreviation for “MPEG Audio Layer III.” The MPEG part of that abbreviation is yet another abbreviation, this time referring to the Moving Picture Experts Group, an alliance of groups created by the International Organization for Standardization and the Fraunhofer Institute for Integrated Circuits and tasked with setting standards around digital media encoding. According to NPR, the concept behind the MP3 everyone knows today traces its roots to 1982 but it was deemed technically impossible until the late ‘80s and early ‘90s. The .mp3 file extension still used by many today traces its first birthday to July 14, 1995.

The MP3 was slow to take off in a world dominated by CDs and may actually owe some of its eventual ubiquity to a ‘90s internet pirate. In an interview with NPR, Karlheinz Brandenburg—referred to by some as the “father of the MP3”—said the process of “decoding” MP3s and making them usable for music listeners was essentially hijacked by an Australian student who purchased a professional encoding software for MP3 using a stolen credit card. He then allegedly broke down the software’s inner workings and posted them on a Swedish site with a read-me file titled, “freeware thanks to Fraunhofer.”

“He gave away our business model,” Brandenburg said in a 2011 interview with NPR. “We were completely not amused.” Brandenburg went on to say the MPEG groups tried to hunt down the leaker but the software had spread to a point where it was bigger than its creators could control.

“It was in ‘97 when I got the impression that the avalanche was rolling and no one could stop it anymore,” Brandenburg added. “But even then I still sometimes have the feeling like is this all a dream or is it real, so it’s clearly beyond the dreams of earlier times.”

The stolen business model would lay the groundwork for the widespread adoption of relatively tiny music files and portable MP3 players. Brandenburg may have missed out on a payday, but Apple made money hand-over-fist.

The introduction and eventual acceptance of MP3s paved the way for possibly the most significant and controversial ‘90s music innovations: Napster and peer-to-peer file sharing.

Over the course of fewer than three years, Napster would rise and fall, acquire millions of curious users, and upend ideas around music ownership and distribution for decades to come. Napter’s founder, a college student named Shawn Fanning, reportedly articulated his idea for the service on an internet message board in 1999. Referred to by many as a “glorified file browser.”

Napster worked by letting users see MP3 files available on other computers and access them. By doing so other users, or peers could then access files on their computers in turn. The result was a dramatic and radical expansion of the amount of music potentially available to any one listener that hurled the industry out of the limited confines of CDs.

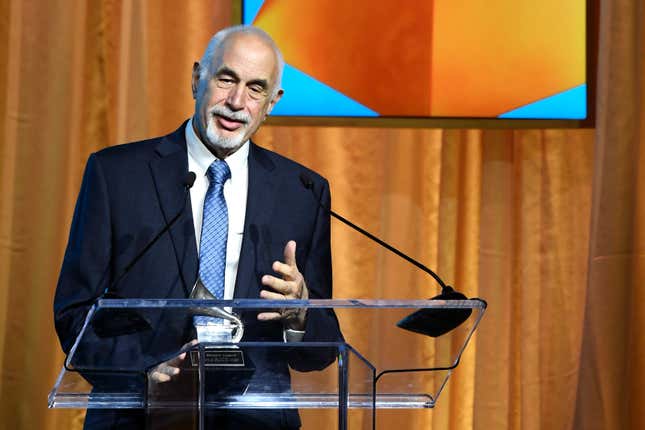

“There was no ramp-up. There was no transition,” Downloaded director Alex Winter said in a 2013 interview with The Guardian. “It was like that famous shot from 2001: A Space Odyssey when the prehistoric monkey throws a bone in the air and it turns into a spaceship. Napster was a ridiculous leap forward.”

Napster launched in May 1999 and reportedly had 4 million songs available in circulation by October of that same year. By March 2000, the site had amassed over 20 million users and by the summer, some 14,000 songs were reportedly being downloaded every minute.

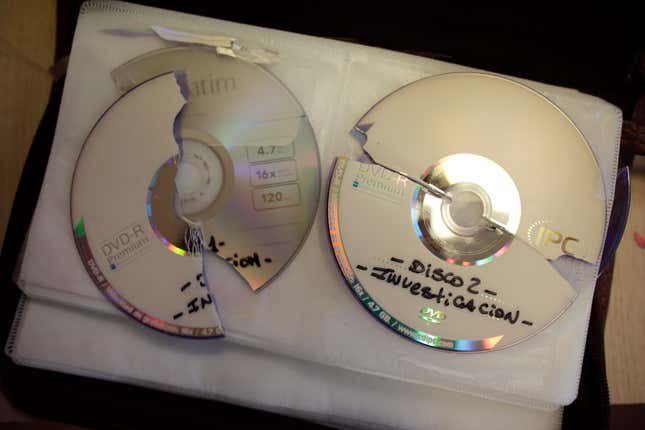

Backlash from the record labels who felt like they were being denied compensation for songs they owned was strong and swift. Labels, led by the Record Industry Association of America, tried to bury Napster in a barrage of copyright lawsuits. Musicians, most notably Metallica and Dr. Dre. also launched their own heated, high-profile campaigns against the startup, but Napster wasn’t the only one feeling the heat. Individual Napster users, reportedly as many as 18,000 of them, were also sued, sometimes for simply accessing a handful of songs. The end came quickly for Napster. A court judge ruled in favor of RIAA and the site was given just 48 hours to start charging users for music.

Napster was acquired by a company called Roxio and then, in an odd string of events, eventually acquired by retailer Best Buy before being relaunched in 2016 in a short-lived effort to revive the band. Needless to say, that didn’t quite work out. Still, Napster’s legacy lives on in modern streaming services that cut deals with the record industry that realized it couldn’t compete with the bargain basement price of free.