A shocking coup attempt sent South Korea into political upheaval. But on the ground, at the protests that would prevent the President from seizing power, people were organized, angry, and a little drunk.

Share this story

When the South Korean president declares martial law on Tuesday night, I am fairly drunk, as is much of the city. By sheer coincidence, I am working from Seoul that week, and I have just met up with my boss — also, coincidentally, passing through the city while on vacation — for drinks. My boss’s boss texts me at 10:49PM as I stumble out of the subway station and into a convenience store where I proceed to buy an armful of hangover cures. “Did South Korea just declare martial law?”

I laugh. Impossible. That can’t be true. “I think that’s literally fake news,” I text back. I’m walking on the street and everyone around me is behaving completely normally. There are no soldiers, no cops, no loudspeakers — absolutely nothing to indicate that martial law is in place. Nothing in the news leading up to the day suggested that this was in the works. There were definitely some odd things happening in Korean politics, but what else is new?

No emergency alert has been issued. Cellphones in the country tend to buzz frantically with mandatory push alerts for all kinds of things: elderly people who go missing in the vicinity, traffic accidents downtown, even an alert for a North Korean balloon filled with propaganda and trash that was floated over Seoul last week. Think Amber Alerts, but broader.

Still, no official notifications about martial law.

But when I check Reuters, I am in for a rude awakening. Oh damn. I am living under martial law.

To be brief, the conservative President Yoon Suk Yeol is a controversial figure. From the moment he took office he was up to some weird-ass shit, like moving the president’s office out of the historic Blue House. (To give you a sense of how bizarre the news cycle got, Yoon had to issue a denial that he did so on the advice of shamans.) Misogynistic anti-feminism has been a component of building his powerbase, as has the persecution of journalists. But the central tool in his arsenal has been anti-communist fear-mongering, a play that does in fact work in a country that lives next to a bellicose and volatile North Korea.

But the playbook has not been working so well as of late. Protests demanding his impeachment have been intermittent in Seoul over the past months. Of course, the presence of political protests are not unusual in South Korea: this is a nation that lionizes the protesters who opposed the dictatorships of the 1970s and 1980s, and teaches young schoolchildren to revere the 1919 protests against the Japanese colonial occupation. But it’s not just rote opposition politics — even relatively conservative newspapers are criticizing Yoon, and his popularity is in the toilet. It’s against this backdrop that Yoon Suk Yeol made the late-night surprise announcement that the country was now under martial law, in order to stop “shameless pro-North anti-state forces that plunder the freedom and happiness of our people.” All political activities — including those of the National Assembly, the parliamentary body that can legally block his martial law order — were suspended.

At 11PM, an order is issued by General Park Ahn-su, declaring that “all media and publications shall be placed under the control of the Martial Law Command,” and prohibiting political gatherings, demonstrations, strikes, and slowdowns. I hear rumors that there are tanks in the streets. The military is apparently at the National Assembly, trying to block a vote from happening.

I pace inside my Airbnb, running through a list of potential freelancers I can commission to write about what’s happening in Korea, but no one is available. I do not report on Korean politics, nor do I have enough language proficiency to interview people on the street. Also, I am completely blasted, though maybe not unusually so in Seoul on a weeknight. At dinner we were seated by a group of men with maybe a dozen empty liter bottles of beer on their table; we watched them wave down the proprietor for even more alcohol. “Wow,” I said, before going on to mix soju bombs for my companions. I sometimes describe Korea as the Ireland of East Asia; I’m not a huge drinker when I’m at home in the US, but the general ambience of Seoul shifts my habits.

As I chug hangover tea, I scroll through my phone, continuing to be baffled that no emergency alert has gone out. My cheeks are flushed and my head is buzzing, and I can’t tell how much of it is alcohol and how much of it is the pure surrealness of living under martial law. I text my brother and I text my cousin, asking if they’ve received an alert, asking them to ask their friends if they have. At 11:30PM I put on my coat and trundle off to the subway, a decision that is equal parts soju and commitment to the principles of journalism. I might as well be on the ground — even if I can’t make sense of what’s happening, the least I could do is witness it.

On the train, I look around, wondering how many people know we’re under martial law right now. People are, for the most part, silently glued to their phones, but that’s not unusual. My brother sends me a screencap of a screencap of a mass text message, possibly sent to registered voters of Korea’s Democratic Party, asking party members to gather at the National Assembly.

Line 1 — practically an internet meme due to how frequently old men get into drunken fights on its trains — is truly in its element tonight. A very wasted guy hollers so loudly in the next car that another man stomps over and passive-aggressively slams the compartment door shut. A girl in a collegiate athletic jacket sleeps through it, head against her boyfriend’s shoulder. A younger man, seated, is exchanging heated words with a very small white-haired man who is ineffectually attempting to loom over him; I cannot tell who the aggressor is in this conflict, but the older man is stumbling and swaying and seems barely verbal.

This is the classic Korean ahjussi: older men from the working or middle class who drink and smoke too much. They hang together in groups at night, yelling and swearing, either in a rage or simply jovially cajoling each other into going to another bar to drink more. These men don’t truck with newfangled things; they don’t really understand kids these days and how disrespectful they are; they have old-fashioned ideas about the nuclear family and birth rates; they prefer rice to pasta and they don’t think a meal is complete without kimchi. You’d think that Korean men are issued a standard uniform at the age of fifty — a navy blue jacket, a brimmed cap, and a packet of cigarettes.

This is, of course, an oversimplification of a body politic that is composed of complex individuals. More importantly, a conservative value set does not necessarily translate to conservative politics. These older men were young during the dictatorship, and they lived through the student protests and the bloody Gwangju uprising. It’s tempting to cast them in opposition to a younger generation that tends to vote liberal and is less prone to anti-communist redbaiting. But the ahjussis were once young too, and in their youth they ushered South Korea into a true liberal democracy.

When I transfer to Line 9 to get to the National Assembly building, the energy is subtly different. I realize that I’ve never seen this many Koreans taking phone calls in public. As I get off at the National Assembly stop at 12:30AM, the entire train empties out with me.

The sudden vibe shift starts with a middle-aged aunty sitting on a platform bench waiting for the other train who shouts “Fighting!” at the crowd that packs the escalator and the stairs. Another woman in a motorized wheelchair yells political slogans as she zips ahead to the exit, fist in the air. When I emerge into the freezing night air, the first thing I see is military uniforms. My heart races and I take out my phone, before realizing that the two young men in full body tactical camo look frightened. The soldiers are surrounded by furious ahjussis pushing and shoving and cursing at them.

The crowd is chanting “Impeach Yoon Suk Yeol!” Blue and red lights flash everywhere. Police buses line the streets; the major TV stations have sent vans and camera crews. The crowd is about evenly split between the young and the old, and it is the old that are the loudest and angriest. “How dare the military come here!” an ahjussi swears.

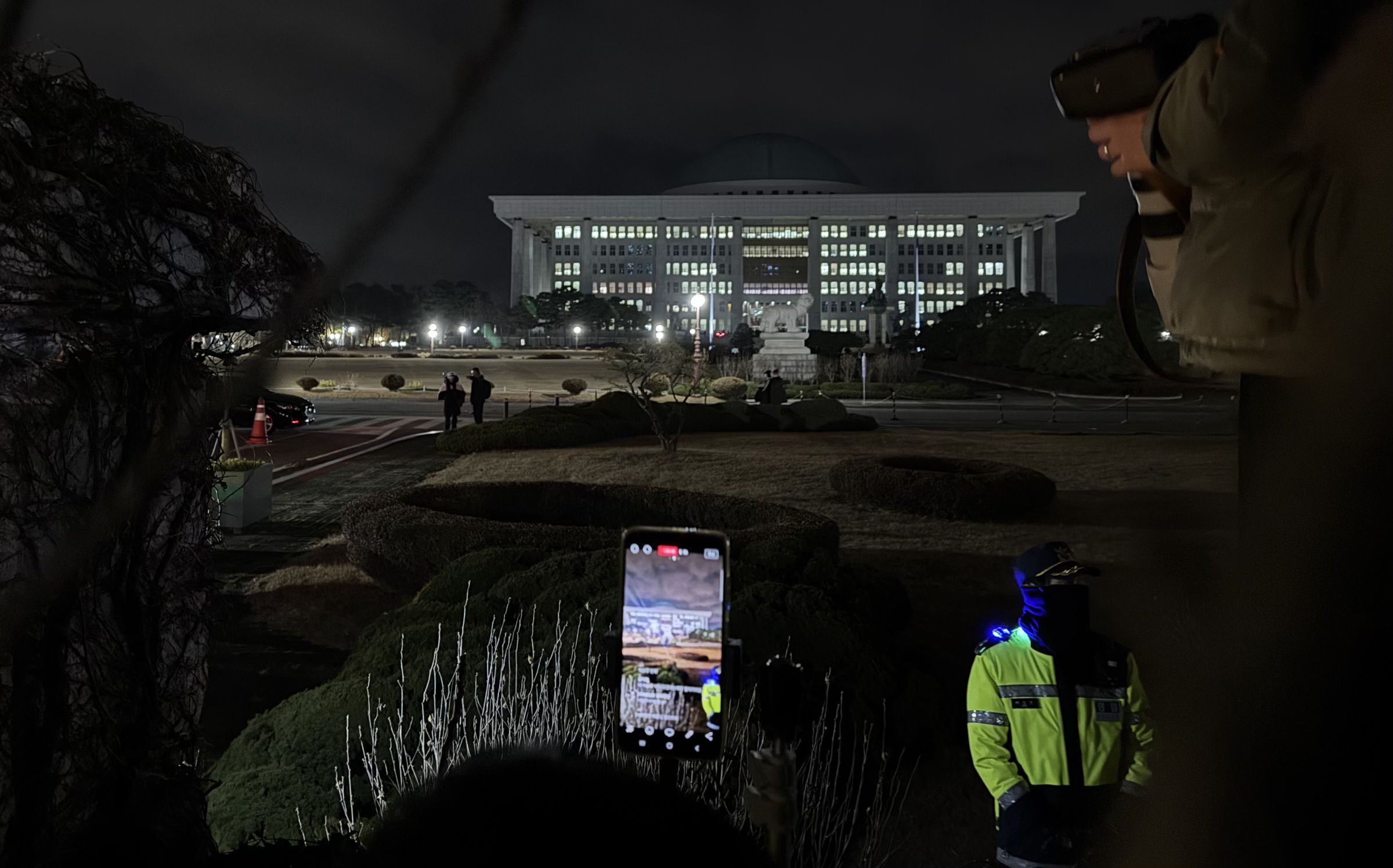

A few minutes later I hear the thunder of helicopters overhead. (The news later reports that military helicopters landed on the other side of the building, carrying soldiers to invade the National Assembly. About an hour before I arrived, the leader of the liberal opposition party livestreamed himself scaling a fence in order to get to the Assembly building to vote.)

Before I can even really process it, I can no longer see soldiers on the street. There is still camouflage here and there, but these are a smattering of protesters wearing it head-to-toe, possibly vestiges of their own time doing mandatory military service. Hordes of riot police with shields and neon green vests are marching through the streets. The protesters are ignoring them.

An unidentified man gets on a microphone and begins narrating updates; he starts by asking the crowd to surround him and protect him from having the mic taken by the police. The protesters oblige in an orderly fashion.

It’s freezing out, and people are mostly bundled up in puffer coats. I wonder if anyone else can tell how drunk I am; I wonder, also, how drunk other people are. On television, politicians who sprinted to the National Assembly to stop the fall of democracy are blinking slowly and slurring their words. They appear to have been enjoying their Tuesday night in very much the same fashion I had been.

At 1:02AM, the man on the microphone announces that the Assembly has voted to block the declaration of martial law; a heartfelt cheer goes through the crowd. The loudspeakers begin to play some truly awful music, a tinny version of a cheesy protest song that sounds like it was recorded by literal children. The crowd sings along; the ahjussis seem to know all the words by heart. I look up the lyrics later; they roughly translate to: The Republic of Korea is a democratic republic. The power of the Republic of Korea stems from its people.

The chants switch to “Arrest Yoon Suk Yeol!” and “The people are victorious!” The crowd presses against the fences that barricade them from the National Assembly building. Most of them are on their phones, following the events happening inside; some of the older men having their phones pressed against their ears, listening to news broadcasts.

One kid with an open beer slurs, “Death to Yoon Suk Yeol!” and is ignored. People are standing on top of tall decorative planters, on top of walls, on top of piles of unassembled police barricades that have been abandoned. The people standing on the walls are a mix of young men and ahjussis; I am starting to see selfie sticks and GoPros and livestreamers enter the crowd. An ahjussi yells at great length about how much he loves his friends for coming out with him to protest. I can’t tell if he’s drunk or just very emotional. I hear two older men behind me talking about what it was like in the 1980s, I catch a snippet of quiet conversation between younger women — “This is real history,” one says. A protester in camouflage stands at the gate waving what appears to be a stolen riot shield. Another protester hops onto a pile of barricades and takes a selfie with a peace sign.

The number of riot police seems to be shrinking. I see a police bus door shut; I catch a glimpse of dozens of neon green vests piled inside its confines. A woman chuckles, “Yeah, go on home!” The crowd is getting bigger and bigger; the New York Times later reports there are thousands of people on the street. In the moment, I attempt to do a rough count before I realize I am still a little too buzzed to do it.

By 2:30AM the temperature is dropping and I’m starting to feel the cold. The composition of the crowd is shifting — the newcomers are younger and there are more women than there were before. Pressed up against the fence are the most energetic protesters, who are shouting to be let in. I see two people scale the fence; I do not know what happens to them after. Further away from the fence, protesters are engaged in loud, disciplined chants — ”Impeach Yoon Suk Yeol,” “Arrest Yoon Suk Yeol.” A few feet from that ball of people, there is a curb where the unofficial smoking area has opened up. The air is thick with the smell of cigarettes.

A couple of kids ask another protester to please take a photo of them. There’s some kind of surreal musical political satire pantomime on the street featuring a man in an LED-festooned balloon suit. I am almost sober now but it doesn’t feel like it. At 3AM the loudspeakers play a version of “Auld Lang Syne” with Korean lyrics that I think are political — I don’t know enough Korean to be able to tell. An ahjussi near me belts out the words with feeling. People have taken their phones out and have turned on the flashlights so they can wave them around like they’re lightsticks at a concert.

The protest is still going strong at 4AM but I am too cold and too sober to be able to stick it out. I begin to leave the area; on my way out, I see a red-faced puddle of a drunk man being tended to by a cop — one who is not in one of the green vests I’ve seen throughout the night. He doesn’t seem to be in legal trouble; he’s just too wasted to be able to stand.

When I finally catch a cab, the gray-haired driver asks me if I was at the protests. When I answer in the affirmative, he thanks me. I am embarrassed; my Korean is not good enough to explain to him that I am a journalist, that I am an American, that I am supposed to be an impartial observer of history. The ahjussi goes on to tell me he’s always hated Yoon and complains about being called a commie for saying that Yoon was going to ruin the country. He is listening to some kind of internet livestream commentator as he drives me home; I can see the video feed playing on his phone on top of his GPS map; he clucks and shakes his head and noisily reacts as he listens. He asks me rhetorically about what the elites are doing to stop this situation. I don’t have an answer.

He curses at every police bus we see on the way back to my Airbnb.

The president formally lifts the martial law order while I’m taking off my makeup. My body is exhausted, my brain is racing, I can barely make sense of the news as I try to catch up. It’s too soon to reckon with what happened, or to figure out what happens next. I see the screencaps of Lee Jae-myung livestreaming himself climbing the wall at the National Assembly; I think about the GoPros and livestreamers; I think about the kids asking to have their picture taken, so they can tell their families that they were there on that important day. Politics is being intermediated so smoothly through technology that it has become almost unnoticeable, embedded into the fabric of life for the young and the old alike.

It occurs to me that I still have yet to receive an emergency alert. I wonder who controls that system, and who sends out those alerts.

Yoon tried to take power with soldiers, police, and helicopters — to take the country back to the 1980s. But these aren’t the 1980s. He should have seized cell service first.