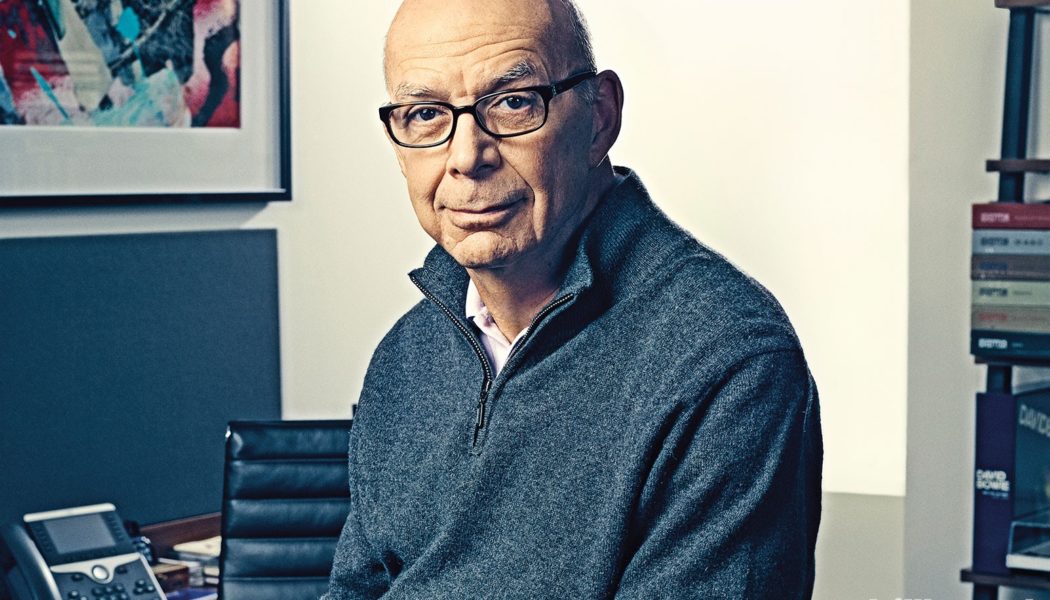

“There are tens of thousands of tracks that are uploaded every day to streaming services around the world,” said Cooper. A label such as Warner, he said, helps artists “separate their music and their careers from literally all of this noise.”

As for Warner’s finances, looking at trailing 12-month revenue, which removes the effect of any one quarter, Warner improved by 13.2%. Physical sales returned to normalcy, climbing from $51 million in a pandemic-stricken quarter a year earlier to $130 million; the quarter included Record Store Day on June 12, which led to record one-week vinyl sales in the U.S., according to MRC Data (next quarter’s earnings will benefit from the July 22 Record Store Day, the second-highest ever). Growth in streaming revenue was adequate at 22.5% for recorded music close to Universal Music Group’s 23.8% improvement — but well behind Sony Music’s 60.3% streaming gain (recorded music and publishing) that drove its 54% jump in total revenue (though you must take into consideration that Sony’s prior-year quarter was weak).

Warner Music’s share price rose 1% to $37.35 on Tuesday but dropped 2.7% to $36.36 on Wednesday, giving it an enterprise value of $22.3 billion.

Here are five key takeaways from the data and discussion:

ARPU and the Subscription Pricing Saga

With the possible exception of Apple’s unbundling of the album format, streaming royalties have been the most controversial music business topic of the last two decades. So, Spotify’s decision to pass small price increases to customers in 42 markets was met with muted applause by rights owners and creators and with interest by the financial community. Most notably, Spotify claimed the price increases had no noticeable adverse effect on customer churn.

“We have no reason to believe that to be anything but completely true,” said Levin.

In fact, Warner is having the same conversation with Spotify’s competitors.

“We’ve been vocal over the years that there’s a real price upside opportunity,” said Levin, adding he “would be highly supportive” of other subscription services that consider “similar steps that are appropriate for their platforms.”

That would be more good news for Warner Music’s bottom line adjusted OIBDA, which gained 52% in the quarter and 30% over the previous nine months. Adjusted OIBDA margin improved from 19.4% to 22% in the quarter and from 20.9% to 22.9% in the nine-month period; Cooper chalked up margin improvements to a combination of growth and cost containment, and a decrease in low-margin merchandise and concert promotion revenue — a trend that will reverse as touring resumes. Nevertheless, subscription price hikes matter when average revenue per user (ARPU) is weakening and streaming is 58% of total revenue and growing.

Real money from emerging digital platforms

Warner receives $235 million at an annualized basis in recorded music royalties from developing sources such as social platforms like Facebook and TikTok; Roblox and other games; and fitness platforms such as Peloton. That was a big jump from the $200 million annualized run rate the company revealed just three months ago.

It’s difficult to predict which social platform will become a source of meaningful royalties, but safe to assume that social media will play an influential role in the future. Facebook and TikTok are such large platforms that labels and publishers can expect them to become major payers. Warner Music wouldn’t say the amount its publishers receive from these developing sources, but Levin said the proportion of publishing royalties to recorded music royalties would follow the one-to-five ratio common in music streaming.

Surviving an M&A Arms Race

In the ’70s and ’80s, Cold War-era spending on military technology helped bring down the Soviet Union. In 2021, a music company can understandably feel an impulse to ramp up spending on music rights and other assets. But quarter after quarter, Warner Music executives have said they won’t get caught in an arms race.

It’s not that Warner won’t spend money: on Tuesday, Levin noted that Warner invested $338 million in recorded music and publishing assets with a OIBDA run rate of $37 million. (A $250 million bond sale to help fund two undisclosed acquisitions was announced in October 2020.) And Warner has put money into Roblox, Wave and Dapper Labs, among other tech companies. But Cooper reiterated his disinterest in becoming asset managers and playing interest rate arbitrage. Instead, Warner favors a traditional approach of being “a proactive music entertainment company” that signs and develops artists and songwriters.

Aside from music rights, Warner invests to “future-proof” the business internally and externally, as Cooper phrased it, a nod to its tech investments. Even as its debt-to-EBITDA ratio declines, Warner intends to invest in its business and pay dividends rather than pay down its debt, said Cooper.

Are virtual artists here to stay?

What song best describes a new breed of computer-generated artists? “Ain’t Nothing Like the Real Thing” by Marvin Gaye and Tammi Terrell or White Zombie’s “More Human Than Human” (a reference to the lifelike androids in the movie Blade Runner)?

We may find out sooner than you think, as major labels are among the investors giving virtual artists an opportunity for mainstream success. Warner Music’s bet is Spirit Bomb, a real record label with a roster of virtual artists recorded by real musicians. Cooper called virtual artists “not an illogical next step” and said Warner is “determined to lead the crossovers of these virtual beings into the music world.”

There is some precedent — however prehistoric — that suggests virtual artists will find welcoming fans. Gorillaz, created by Damon Albarn of the British band Blur and comic artist Jamie Hewlett, sold 24 million albums worldwide, according to its label, Parlophone, and has amassed 7.3 million album sales (with track equivalents) and 3.5 billion on-demand streams in the U.S., according to MRC Data. And Crazy Frog, a CGI character created in 2003, topped the charts throughout Europe with “Axel F” (it only reached No. 50 on the Billboard Hot 100). But those examples share little in common with the high-definition animation and artificial intelligence-created music of today’s virtual artists. Now, people live comfortably in a virtual world. Expect other labels to also invest in this space.

Can major labels remain relevant?

Any investor or analyst should wonder how Warner — or any other large music company — can attract and retain artists when artists have a growing number of options to remain independent. From raising capital to digital marketing, a large infrastructure provides artists the basic functions of a record label. Can those artists remain independent rather than signing with a major label? Absolutely, and anybody modeling a company’s valuation and stock price needs to take these dynamics into account.

With Vivendi soon spinning off Universal Music Group, more people are poking and prodding the major label model. During the earnings call, Cooper took an opportunity to defend major labels’ value to artists.

“When you look at well-established, tremendous global superstars, all of whom have had the opportunity to pivot away from labels, utilize the digital tools available and go solo, so to speak, by way of moving their career along, virtually none of them have taken that decision to pivot away from labels.”

That may be true, but an investor or analyst should consider that new tools and services help give artists a career with IP ownership, more freedom and agency in their careers — and some artists will choose that over a global powerhouse.