In a floor-through loft in SoHo one Friday night in January, Vincent Ferraro was selling luxury clothing. Sort of.

On one side of the room, a tattoo artist covered a young woman’s palm in an illustration of a bankroll. Some people flipped casually through the racks of Chrome Hearts and Enfants Riches Déprimés, but Mr. Ferraro — sinewy, with a shaved head and covered in tattoos — didn’t pay them much mind. Instead, he poured shots of Patrón, posed for Instagram photos and occasionally disappeared with one of the several women who had come to vie for his attention.

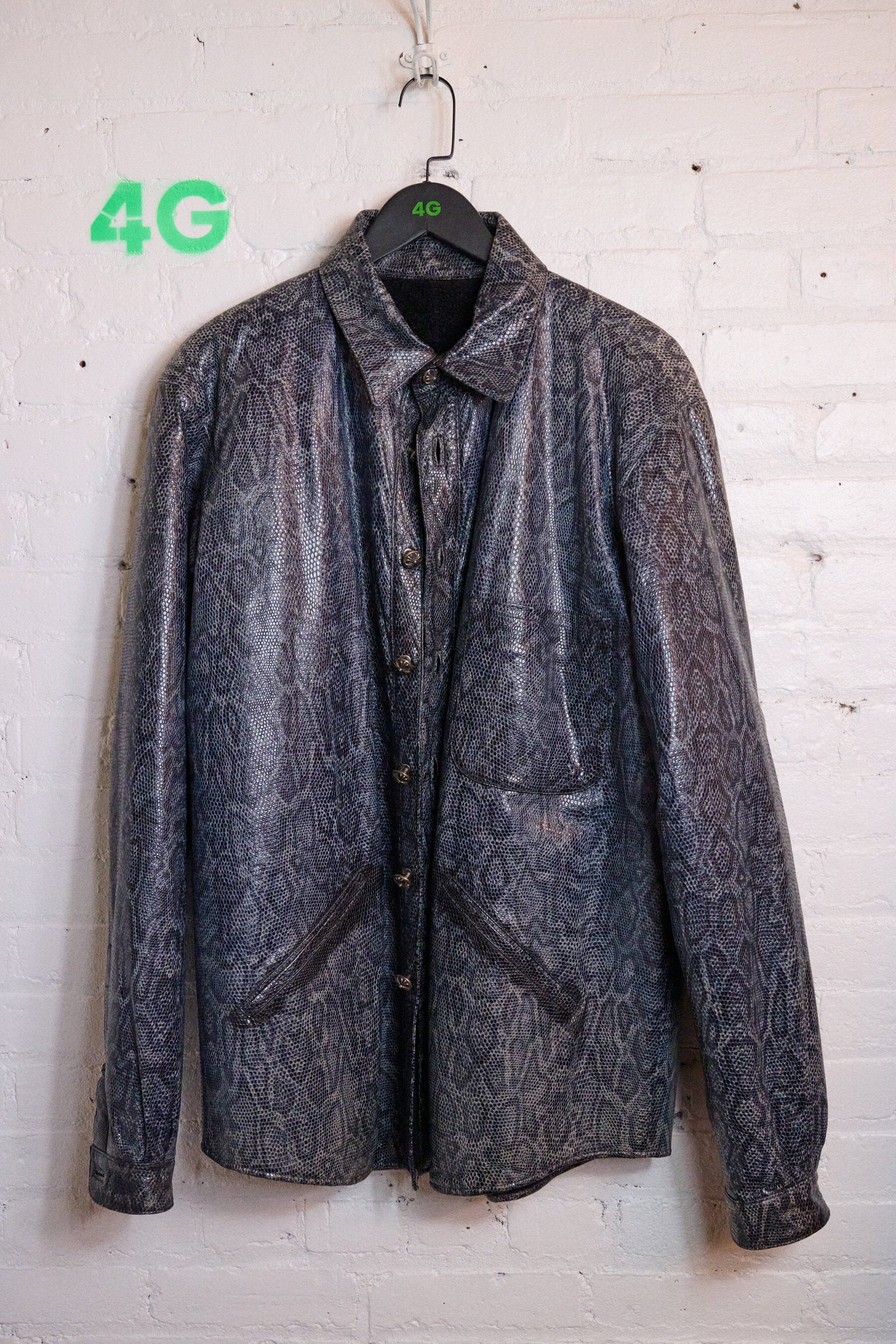

On the men’s resale clothing site Grailed, Mr. Ferraro, who before the pandemic worked in nightlife, most recently as general manager and creative director of Rose Bar at the Gramercy Park Hotel, sells under the handle 4GSELLER, and in the last couple of years, has become the go-to for rare Chrome Hearts, recent-season Louis Vuitton statement pieces and thrashed vintage dirtbag T-shirts, building a business that he says has annual revenue in the low seven figures.

“I did take, like, a big page out of what I did hospitality-wise and integrate it into what I’m doing,” Mr. Ferraro, 32, said a few weeks before the party, relaxing in the showroom one afternoon in a Yankees fitted cap, white T-shirt and Louis Vuitton ski pants. On the couch next to him he had a small pile of new Chrome Hearts inventory, and one piece in particular stood out: heavyweight black leather cargo pants with exaggerated pockets and built-to-last hardware.

The pants had an original retail price, he said, of around $6,000 to $7,000, but he was planning on listing them for north of $20,000. “The guy who got these waited a year,” he noted, referring to the sometimes lengthy wait for Chrome Hearts orders. “But people aren’t coming here to wait a year. They’re coming to walk out with them right now. So there’s a value to that.”

Still, $20,000 is a few mortgage payments, a diamond necklace, a painting, maybe a small car. Is there no sticker shock?

“I sold three of these already,” he said, not even blinking.

Welcome to the wild world of men’s luxury resale, which has begun to boom in recent years, owing in large part to the graduation of the young male customer who came of age in the era of limited-edition sneakers and Supreme items as asset classes, and for whom hip-hop icons and sports superstars are also high-fashion heroes.

All of those trends have primed the pump for the luxury men’s resale market, which is broadening rapidly, a growth captured in sellers like Mr. Ferraro; Justin Reed, whose Los Angeles showroom has become a celebrity playpen; and Luke Fracher, something of a modern garmento, who recently opened Luke’s, the first buy-sell-trade shop in New York for this generation of men’s luxury clothing.

“We’re seeing the streetwear-ification of high-end,” Mr. Fracher said over dinner in January at Ludlow House in Manhattan, a few blocks from his narrow-corridor shop just north of Dimes Square. Which is to say that the category of current men’s luxury isn’t Loro Piana and Kiton, but rather Louis Vuitton and Balenciaga, Chrome Hearts and Rick Owens, rare Nikes and archival Raf Simons.

That evolution has been unfolding for more than a decade. There’s an explicit through line from Riccardo Tisci’s invigoration of Givenchy in the early 2010s to Alessandro Michele’s psychedelic-tapestry rebrand of Gucci, to Kim Jones’s streamlining of Dior to, of course, Virgil Abloh’s up-from-spare-parts reconstruction of Louis Vuitton. And by remaking Nike and Vuitton simultaneously, Mr. Abloh implicitly linked their audiences, making clear that a luxury item is something people are willing to splurge on, regardless of which company made it.

Mr. Fracher, 34, was a founder of the Round Two empire, which during the 2010s turned the secondhand T-shirt trade into a multimillion-dollar concern with nine locations in five cities. He left Round Two last year and opened Luke’s in December, betting that some of the customer base that cut its teeth on streetwear and sneakers would be ready to upgrade to something fancier.

He also pointed to how insatiable social media feeds have created persistent and renewable demand for luxury clothing. “First of all, it’s the homogenization of how everyone dresses in every city across the world,” he said, emphasizing how clothing has become a globally spoken language. “And then it’s the need to flex nonstop and the need to have new clothing all the time, so you can post fit pics and get the dopamine hit and hopefully get some clout off it.”

Because he buys his inventory outright and has little room for storage, Mr. Fracher wants to move product quickly, most likely leaving him with thinner margins than those of Mr. Ferraro or Mr. Reed, who operate as showrooms with online presence.

Mr. Reed’s space, in a warehouse building in the downtown Los Angeles arts district, is bucolic and soothing, almost spalike. At the center of the main room sits a four-section de Sede Terrazza sofa from the early 1970s, still in its original beige leather, that he bought from a Hollywood producer. It’s been a fixture on his Instagram for a few years, giving him a unique, sophisticated visual identity as his website, which he started in 2017, was getting on its feet.

Now Mr. Reed, 35, is one of the most trusted names in men’s luxury resale. At his showroom, which during a December visit was decorated with a Givenchy surfboard, artwork by Joyce Pensato and a bench from the spring 2022 Louis Vuitton runway show, he entertains celebrity clients like the boxer Gervonta Davis, the Buffalo Bills wide receiver Stefon Diggs, the longtime fashion plate Luka Sabbat and Shai Gilgeous-Alexander, point guard for the Oklahoma City Thunder, all memorialized in a wall of Polaroids. (Mr. Reed said that only about a quarter of his business comes from celebrity clients.)

Mr. Reed, in a St. John’s hoodie — his alma mater — and Balenciaga Strike boots, described himself as “a self-taught street kid.” Born and raised in New York, he sold photocopiers door to door before beginning to resell sneakers online in the mid-2010s. Once he began focusing on luxury men’s items, he effectively helped make the marketplace thanks to a sleek web presence and a reputation for sourcing rare pieces. Last year, he sold one of the only known jackets by Pastelle, an early Kanye West brand, to Kim Kardashian. Like Mr. Ferraro, he does brisk trade in Chrome Hearts, especially odd, rare items like a leather case for jumper cables, or a weight bench.

Unlike Mr. Ferraro, he runs most of his business on consignment — his 2022 revenue was approximately $8 million, he said, roughly doubling each year since 2019. His average website order is $1,300, he said, and around 100,000 people visit his site each month with almost no advertising.

Broadly speaking, hip-hop is to thank. Rappers began to embrace luxury fashion in the 1990s and 2000s just as the genre was muscling its way to the center of American pop music. By the 2000s, Kanye West and Pharrell Williams were deepening the ties between music and fashion, making way for the generation of ASAP Rocky and Tyler, the Creator, followed by Travis Scott and Playboi Carti. (This attitude has spilled over into professional sports, especially basketball and football, where players are now routinely filmed and photographed in the outfits they arrive at games wearing.)

In a way, high-fashion items have supplanted the rapper chain as the de rigueur splashy purchase. “You got to be dripped out to show people like, ‘Hey, I’m here and I’m going to wear $10,000 jeans, drag ’em on the ground, and I’m going to make more money,’” Mr. Ferraro said.

By the mid-2010s, being a fan of hip-hop almost implicitly meant becoming a style aficionado, and starting to learn to dress the part. Around the same time, Grailed was introduced, formalizing a chaotic web of sales that mostly took place in online forums and building a true, transparent marketplace out of what had largely been hand-to-hand transactions. Furthermore, no longer did someone have to speak in the specific argot of forum loyalists in order to have access to rare product.

Arun Gupta, the co-founder and chief executive of Grailed — which last year was acquired by the GOAT Group, which also owns the sneaker reseller Flight Club — said that sales of luxury clothing had grown year over year, thanks to increased customer education.

“The level of knowledge has gone crazy,” Mr. Gupta said. “The number of fashion brands that the average fashion person knows has probably 10x’d. Self-expression in the ’90s was your CD collection, but in the 2020s, it’s about your closet.”

Before Grailed, to the extent that there was luxury resale for men’s clothing at all, it was limited to consignment shops, like the one Ina Bernstein opened on Thompson Street in Manhattan in the early 1990s. Originally, she did not carry men’s clothing in her namesake store. Eventually, some trickled in — suits and ties, Armani and Calvin Klein, maybe a little Yohji. By the mid-1990s, she had opened a small men’s-only storefront on Mott Street. Customers were dedicated, but scant. Men weren’t quite ready. “It was very weird for them to think about trying on someone else’s clothes,” she said in a phone interview last month.

But the social conventions of male dress were on the verge of disruption. Soon, luxury houses were making more than officewear for men, and a wider swath of male consumers took an interest in expensive clothes. Ms. Bernstein’s customer base widened accordingly, she said: “It’s drastically changed. Many men who do not work in the fashion business, never went to art school. They’re just walking-down-the-street men, and they all love fashion.”

Even just a decade ago, the audience for some of the rarer men’s luxury items was almost comically small. Alex Kasavin, before opening Idol in Brooklyn in 2014, resold niche high-end men’s clothing, like Carol Christian Poell and early Rick Owens, through a showroom called the Gray Market beginning in 2012. “There was a time with those brands, for these key pieces, I would know almost every owner,” Mr. Kasavin said. “There wasn’t a whole generation that grew up on it. Now there is, and that generation has buying power.”

It also has a robust understanding of how clothing in this category holds its value. “It’s like buying stocks now,” Mr. Gupta said, adding that expensive purchases now involve less risk because of the stability of the resale market.

This growing market is also attracting the attention of luxury brands and retailers. Mr. Reed said that he had been approached by larger fashion players interested in forming a partnership with him: “I think I can be the Barneys of the secondary market.”

Mr. Ferraro, for his part, would rather remain niche. “I’m not trying to be, like, a $50 million business,” he said. “I’m trying to stay genuine to the products.” He sells across the modern luxury spectrum, including Saint Laurent and “Decarnin-era only” Balmain, but Chrome Hearts is his bread and butter and, in a way, his public persona. He is effectively a stand-in for his customer base, which includes rappers like Lil Tecca, rockers like Travis Barker, and athletes like Odell Beckham Jr. and Travis Kelce, who stopped by Mr. Ferraro’s showroom not long after his Kansas City Chiefs won the Super Bowl last month.

“Tecca or Odell will come here, and we’ll go out after,” Mr. Ferraro said. “And then we’ll come back here, and they’ll buy clothes.” He once was summoned to Offset and Cardi B’s home on Father’s Day to show Cardi some rare Chrome Hearts pieces. He has even sold vintage Chrome Hearts to Kristian Stark, scion of the brand’s family.

But he’s not precious, believing that even at these perilous prices, these garments are meant to be worn. The day before the interview, a handyman had been in the showroom doing some work. “We had the TaskRabbit in Chrome!” Mr. Ferraro exulted.

Mr. Fracher said that Mr. Ferraro’s casual roisterousness was central to his appeal. “I knew Vincent from Rose Bar,” Mr. Fracher said. “He used to comp us tables and bottles. He’s a psycho like me. Vinny is, like, almost like a fashion house designer. Like, he reminds me of Hedi or Demna, in the sense that he built a lifestyle and then portrays it.” (Nightlife is in Mr. Ferraro’s blood — one of his uncles is Ron Galella.)

Mr. Reed, on the other hand, is “like a jeweler,” Mr. Fracher said. Of the three sellers, Mr. Reed’s business is the biggest, and his attention to the market is finely detailed. He’s made a few micro-markets in recent years, getting in early on the Chrome Hearts denim resurgence and selling some of the only Prada collaborations with Frank Ocean’s luxury brand Homer that have hit the resale market.

What the ceiling for this luxury resale marketplace may be is yet to be determined. Clothes are increasingly detached from scene and subculture, so there are many more style propositions in demand at any given moment. But there’s only so much product of this level being manufactured, and only some of it is in circulation at any given time.

“The athletes, the entertainers — they hold, they don’t want to sell,” Mr. Reed said. “What I think they like is having a closet that’s like a store.”

Often, Mr. Reed and Mr. Fracher find themselves selling to other resellers in different cities, or with different clienteles. “Part of what keeps the market propped up is that so many people see what those guys are doing and want to do it,” Mr. Kasavin said.

If Mr. Ferraro is a lifestyle ambassador and Mr. Reed is an asset manager, then Mr. Fracher is a yenta. A freewheeling presence on TikTok and Instagram, blending his thorough knowledge of the marketplace with a sense of wry exasperation, it sometimes feels as if he is advertising clothes by indicating how preposterous he finds them. To sit with him over a few afternoons of haggling is to become lightly unromantic about the purported exclusivity of luxury clothing. Expensive items, some rare, seemed to walk in out of nowhere.

“Luke is really the new Ina,” Mr. Kasavin said.

Mr. Fracher traded two smallish Rick Owens jackets for a few Balenciaga pieces from a fashion hound wearing an early Vetements hoodie. One man tried to sell him the Enfants Riches Déprimés hoodie off his back, but couldn’t agree on a price. Someone came in to offload a shirt from Yeezy Season 5. “No one is buying that,” Mr. Fracher shrugged.

Seeing these expensive items treated so casually threatened to undermine the concept of luxury itself. If everyone is dressing up, then is anyone really dressing up? But it also suggested the true circularity of the marketplace, the scale of available supply, and the potential for endlessly renewable demand, even in the face of a possible recession.

Mr. Fracher is not overly preoccupied by these philosophical concerns, though. “I think as the real wealth gap keeps growing, more and more normal people are going to want to cosplay as rich people, and this is the easiest way to do so,” he said. “I’ll be here for them.”